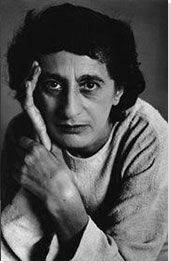

Summary of Anni Albers

Born Annelise Fleischmann, Anni Albers rebelled against her comfortable upbringing to study at the Bauhaus during its most impoverished years. After finishing the foundations coursework, her choices for further study (as a female student) were limited and she began working in the weaving workshop. She quickly embraced the technical and aesthetic challenges of weaving, however, and would revolutionize both aspects of the medium with her experimentation and modern design. She also understood that the Bauhaus needed to create designs that could be industrially manufactured and while she remained committed to the handloom, she also thought of her products as prototypes for mechanical production.

Marrying Bauhaus master instructor Josef Albers in 1925, the pair was central to Bauhaus teaching and artistic production, especially after Anni became the head of the weaving workshop in 1931. When mounting pressure from the Nazi party threatened the Bauhaus, the Alberses were hired at Black Mountain College. While her husband taught a range of art classes, Anni led the weaving and textile design program until 1949, when they moved to Connecticut. There, she continued designing fabrics for mass-production, creating more artistic handloom work, and exhibiting her work to high acclaim. She also began experimenting with printmaking in 1963, after a trip to the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles. Until her death, she experimented with various printing techniques and continued her pursuit of innovative textile design.

Accomplishments

- At the Bauhaus weaving workshop, Albers learned to experiment within the basic structure of weaving and textile design, becoming one of the most prolific and renown members of the workshop. As one of the few profitable workshops, the weaving workshop was central to Bauhaus's vision for the school as a laboratory for industrial innovations, creating new designs for mass production that would bring together good design and modern materials.

- Albers made her mark on the Bauhaus, the weaving art form, and the conception of "women's" crafts with her innovations. Beyond the integration of abstract modernism into textile weavings, Albers also introduced new technologies to the weaving workshop. When the Bauhaus won a commission for the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gerwekschaftsbundes (ADGB) School, it was a testing ground for their ability to craft industrially feasible designs. Albers developed a set of textiles for the ADGB auditorium, using different types of synthetic fibers and cellophane to create acoustic panels. Her research into these materials influenced the manufacturing of similar panels and led to new innovations in theater design.

- In 1949, the Museum of Modern Art, New York exhibited Albers' work, making her the first designer to have a solo exhibition there. This show then traveled throughout America, showcasing her weavings to a large audience and cementing her reputation as the leading textile designer in the country.

Important Art by Anni Albers

Untitled wall hanging

Decorative wall hangings of this sort comprised some of the Bauhaus weaving workshop's most successful products, along with shawls and blankets, yet this was also a space for Albers to experiment and innovate. Unlike her colleagues, she adopted a palette of neutral threads and focused her attention on complicated weaving techniques and modern geometric design. This reflects, in part, her intention to create designs that could eventually become models for industrial mass production. This pattern is based on repeating and interlocking forms of stripes and blocks, created with a triple-weave technique.

In 1924, Albers published an essay, "Bauhaus Weaving" that described both a history of weaving and spoke to its future potential. Noting that very little had changed structurally from the "ancient craft" of textile weaving, she stressed that modern equipment had not revolutionized the basic grid structure of woven cloth. She also laments that current mass production has lost contact with the materiality of weaving and that the divide between designers and weavers has led to poorly designed and poorly crafted products. The Bauhaus weaving workshop, with its synthesis of design and craft emerges as the solution to this industrial stalemate. While she celebrates the handloom (which she would continue to use in her own work), she ends the essay with a vision for modern textile production, based on the designs and materials developed through craft-based experimentation. This particular wall hanging was one of the first to include new synthetic fibers, including artificial silk, which would later become standard materials for mass-produced textiles.

In the sketches for her wall hangings, Albers reveals this combination of weaving technique and modernist design. Her limited use of color was influenced by contemporary theories of color relationships, often reflecting the glass artwork of her future husband Josef Albers.

Synthetic silk, synthetic fibers - Bauhaus Archives

Necklace

The Albers moved to America 1933 when Josef was invited to teach at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. The school would, in time, become a new extension of Bauhaus pedagogy and a center for experimental art. Anni taught weaving and textile design at Black Mountain, but also began working with other materials, including jewelry. Inspired by the combinations of precious and non-precious materials of pre-Columbian jewelry, which they saw during a trip to Oaxaca, Mexico, Albers and her student Alex Reed began to design objects based on common household items.

Beginning in 1940, their collaboration resulted in a series of anti-precious jewelry, constructed from elements purchased at hardware stores or local five-and-dimes. Imagining new uses and unique patterns from unassuming materials such as washers, ribbon, paper clips, nuts, chains, or bobby pins, their jewelry emphasized the modern materiality of these objects and did not attempt to transform them into something more refined or expensive.

Although some critics ridiculed the collection for its common materials, their criticisms revealed the popular expectations of jewelry as a sign of economic display and ostentatious indulgence. The jewelry was well received within the artworld for its imaginative reworkings of familiar objects and its creations of beauty through the form rather than the expense of its components.

Metal chain, dish drain, paper clips - Multiple copies extant

Six Prayers

In 1965 The Jewish Museum commissioned Albers with the challenging task of memorializing those who died in the Holocaust. In this series of six abstract panels, she brings together a limited palette of brown, black and white with silver threads to create a quiet and contemplative installation. Faced with the impossible task of capturing the lives of millions, she instead creates a space for thought and allows the viewer to find more specific meanings. The vertical panels recall the shape of burial markers or scrolls of text, but can also be read as pure abstractions of line and color. The work is approximately six feet high and eleven feet wide, the number 6 is again a reference to the six million Jews murdered by the Nazis.

The panels are not woven uniformly, but rather the black and white threads vary against the structure of the grid. They create a pattern that meanders, ebbing and flowing to suggest any number of individual paths within the whole. The process of weaving takes on additional significance in this work as a reference to tikkun, the notion of "social repair" central to Jewish identity.

Cotton, linen, bast and silver thread - The Jewish Museum, New York