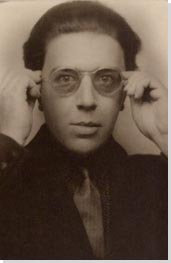

Summary of André Breton

André Breton was an original member of the Dada group who went on to start and lead the Surrealist movement in 1924. In New York, Breton and his colleagues curated Surrealist exhibitions that introduced ideas of automatism and intuitive art making to the first Abstract Expressionists. He worked in various creative media, focusing on collage and printmaking as well as authoring several books. Breton innovated ways in which text and image could be united through chance association to create new, poetic word-image combinations. His ideas about accessing the unconscious and using symbols for self-expression served as a fundamental conceptual building block for New York artists in the 1940s.

Accomplishments

- Breton was a major member of the Dada group and the founder of Surrealism. He was dedicated to avant-garde art-making and was known for his ability to unite disparate artists through printed matter and curatorial pursuits.

- Breton drafted the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, declaring Surrealism as "pure psychic automatism," deeply affecting the methodology and origins of future movements, such as Abstract Expressionism.

- One of Breton's fundamental beliefs was in art as an anti-war protest, which he postulated during the First World War. This notion re-gained potency during and after World War II, when the early Abstract Expressionist artists were creating works to demonstrate their outrage at the atrocities happening in Europe.

Important Art by André Breton

Egg in the church or The Snake

Egg in the church or The Snake is an example of photographic collage that was popularized by Surrealists like Breton and Man Ray. Typical of Breton, the title is both symbolic and enigmatic and its subject matter is cryptic and dream-like. It exemplifies the Surrealist interest in the female body as form, as well as an interest in themes concerning sexuality and religion, as elucidated by Georges Bataille. Bataille's text dealt, in part, with Christianity's repression of desire. Breton and his colleagues aspired to reduce all sexual repressions to symbols and language that would serve freedom of expression.

Collage on Paper - Musée d'Ixelles

Poeme

This is an early example of a Surrealist collage that fuses text and image. Breton wrote this poem the same year he published the Surrealist Manifesto. More than a poetic expression, it reveals Breton's increasing belief in journalism as a potent artistic form as the piece uses newspaper and magazine clipping materials as its source. The text is absurdist and constructs its own logic that would not make sense to a reader trying to understand it as traditional language.

Collage on paper - Elsa Adamowicz

The African Mask

The African Mask is a good example of Breton's studies of Primitive art and its shamanistic potency. Breton was renowned for his mask collection. The first mask he purchased was from Easter Island. While in the United States, Breton traveled around the country, visiting several Native American sites and collecting masks all along the way. He was interested in them as visual objects as well as the metaphorical concept as a window into one's inner mind.

Ink and wax on paper - Mark Borghi Fine Art

Cadavre Exquis with André Breton, Max Morise, Jeannette Tanguy, Pierre Naville, Benjamin Peret, Yves Tanguy and Jacques Prevert

This is an example of an artwork made as an Exquisite Corpse, a Surrealist game developed to free the mind and to tap into subconscious forces, similar to doodling. In this game, artist fold the page into sections and hide previous contributions or build upon one another's collaborative efforts to create a work that is inspired by consecutive artistic moves. In Breton's early development of theories about automatism, he and his colleagues made many of these collages. They also emphasize the act of collaboration, which was a fundamental ideal to both Dada and Surrealism.

Collage on paper - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Estate of Yves Tanguy

Poeme Objet

Breton made many Poem Objects, such as this assemblage constructed around a plaster egg. Many of his Poem Objects were assemblages. The text on the plaster egg in this work translates as "I see / I imagine" though the poem beneath is deliberately cryptic. Like the Exquisite Corpse, Breton made these objects as a reflection of his inner mind, and also thought of them as analytical tools that could be analyzed, like dreams.

Mixed media collage - National Galleries of Scotland

Biography of André Breton

Childhood

André Breton was born in a small village, although his family relocated to a Parisian suburb soon after. He excelled in school and developed literary interests quite early. Breton read the French Decadents, such as Charles Baudelaire, J.K. Huysmans, Stephane Mallarme, and the German Romantic writers, all of whom informed his early thoughts on avant-gardism. By 1912, Breton had a cultivated knowledge of Contemporary art and begun to study Anarchism as a political movement. While he loved the French Decadent artists, such as Gustave Moreau, he began to separate himself from their belief in "art for art's sake," in favor of art that appealed to the masses.

Early Training

While Breton forged his early aestheticism, he studied medicine, completed basic military training and, in 1915, was assigned to work in a military hospital in Nantes. His first poems, Decembre and Age, were written while he worked there as a nurse. It was during this time that he met his mentors, Guillaume Apollinaire and Jacques Vache, who were both admitted to the hospital for war wounds. Breton's hatred of war led him to an intense investigation of Sigmund Freud's psychotherapeutic practices. He developed a passion for psychiatric art that tapped into the subconscious, which informed his interest in Dada, and later, Surrealism. In 1919, Breton began a correspondence with Tristan Tzara, who was formulating early Dada theories in Zurich. The two finally united forces in Paris in 1920.

Mature Period

When Breton arrived in Paris, he was in his mid-twenties and already an established author and editor of an avant-garde magazine, Litterature. While Tzara penned his Manifestation Dada, Breton promoted journalism and live "happenings" as the ultimate statements against the bourgeoisie. Dada performances were not recorded, so the bulk of the campaign only exists today in print, as flyers, posters, manifestos, handbills, and magazines. During this time, Breton organized many readings and events. He, along with other artists, published open letters, newspaper interviews, press releases, and advertisements. They took advantage of the media to disseminate their theories and to attack the idea of art making as an elitist practice.

Because Dada was originally associated with German Expressionism, many French critics disliked it, thus Breton worked to tie this new movement to French literary communities. Dada faded in 1924 due to personal differences between Breton and Tzara. This paved the way for Breton's Surrealism. The Surrealist Manifesto interpreted Breton's experiments with psychic automatism, which became popular in America when he brought exhibitions featuring Surrealist artists to New York.

Late Years and Death

During the 1930s, artists within the Surrealist movement became polarized, some favoring political activism over commercial success. Artists such as Max Ernst, René Magritte and Salvador Dalí pursued furthered connections between dreams and art practice. Breton, who rejected fascism, advocated for political responsibility and consequently many Surrealists followed his cue. Interestingly, many women affiliated with Surrealism, such as Lee Miller and Meret Oppenheim, followed Breton, for his exploration of sexual identity themes at the time.

Breton traveled Europe during the onset of World War II, lecturing against repression of intellectual freedom. Notably, he spent the summer of 1939 with Roberto Matta at his country house, where Matta painted the pieces that would visually introduce automatism to America. Breton again worked as a medic when the war broke out, finally fleeing to New York in 1941. For the next several years, Breton lectured at Yale and other universities about automatism, politics and Surrealism. His influence on the New York School became clear as painters like Pollock and Motherwell applied his theories to their art practices.

When the war was over, Breton continued to write and traveled the world, finally returned to Paris. In the 1940s and 50s, Breton primarily worked on essays and poems, including Arcane 17 (1945), mythological prose set in Canada. He also published Constellations (1959), a suite of poems inspired by Joan Miró's gouache paintings of the same name. He also collected art, especially that of Indigenous peoples. His collection remained intact until 2003, when the Atelier de Breton was dismantled and sold at auction. Some of his collection remains at the Centre Pompidou. The Dossier Dada, an archive Breton built of press clippings and publications related to these various art movements, can be found at Kunsthaus Zurich.

The Legacy of André Breton

The legacy of André Breton is wide reaching and continues to this day. After coming to New York during World War II, his ideas on Surrealism were essential to early Abstract Expressionists, like Arshile Gorky, Roberto Matta, and Yves Tanguy, as well as second generation Surrealists, like Joseph Cornell. He pioneered the concept of fusing art and culture, which became a basic tenet in Pop Art. Breton's use of the media as a tool of art practice also helped shape many contemporary artists who build personas as part of their work. In this way, he foresaw Performance Art, Fluxus, Conceptualism, and what has followed on from those movements. Perhaps above all, Breton's love of absurdist humor continues to inspire artists to the present.

Influences and Connections

-

![Tristan Tzara]() Tristan Tzara

Tristan Tzara -

![Francis Picabia]() Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia -

![Gustave Moreau]() Gustave Moreau

Gustave Moreau ![Jacques Vache]() Jacques Vache

Jacques Vache

-

![Arthur Rimbaud]() Arthur Rimbaud

Arthur Rimbaud -

![Louis Aragon]() Louis Aragon

Louis Aragon -

![Paul Eluard]() Paul Eluard

Paul Eluard ![Comte de Lautremont]() Comte de Lautremont

Comte de Lautremont![Antonin Artaud]() Antonin Artaud

Antonin Artaud