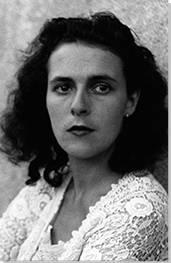

Summary of Leonora Carrington

Leonora Carrington established herself as both a key figure in the Surrealist movement and an artist of remarkable individuality. Her biography is colorful, including a romance with the older artist Max Ernst, an escape from the Nazis during World War II, mental illness, and expatriate life in Mexico. In her art, her dreamlike, often highly detailed compositions of fantastical creatures in otherworldly settings are based on an intensely personal symbolism. The artist herself preferred not to explain this private visual language to others. However, themes of metamorphosis and magic, as well as frequent whimsy, have given her art an enduring appeal.

Accomplishments

- Carrington shared the Surrealists' keen interest in the unconscious mind and dream imagery. To these ideas she added her own unique blend of cultural influences, including Celtic literature, Renaissance painting, Central American folk art, medieval alchemy, and Jungian psychology.

- Carrington's art is populated by hybrid figures that are half-human and half-animal, or combinations of various fantastic beasts that range from fearsome to humorous. Through this signature imagery, she explored themes of transformation and identity in an ever-changing world.

- Carrington's work touches on ideas of sexual identity yet avoids the frequent Surrealist stereotyping of women as objects of male desire. Instead, she drew on her life and friendships to represent women's self-perceptions, the bonds between women of all ages, and female figures within male-dominated environments and histories.

Important Art by Leonora Carrington

The Meal of Lord Candlestick

Completed shortly after her escape from England and the beginning of her affair with Max Ernst, this painting captures Carrington's rebellious spirit and rejection of her Catholic upbringing. "Lord Candlestick" was a nickname that Carrington used to refer to her father. The title of this work emphasizes Carrington's dismissal of her father's paternal oversight. In this scene, Carrington also transforms the ritual of the Eucharist into a dynamic display of barbarism: gluttonous female figures devour a male infant lying on the table. The table itself is a representation of one used in the great banquet hall in her parent's estate, Crookhey Hall. Carrington intentionally inverts the symbolic order of maternity and religion as a statement of her own subversive move towards personal freedom in France.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Portrait of Max Ernst

This early painting by Carrington was completed as a tribute to her relationship with the Surrealist artist Max Ernst. In the foreground, Ernst is shown enshrouded in a strange red cloak and yellow striped stockings holding an opaque, oblong lantern. A white horse, a symbol Carrington frequently included in her paintings as her animal surrogate, is shown poised and frozen in the background, observing Ernst. The two are alone in a frozen and desolate wasteland, a landscape symbolic of the feelings Carrington experienced while living with Ernst in occupied France.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Self-Portrait

This painting perfectly summarizes Carrington's skewed perception of reality and exploration of her own femininity. The artist has painted herself posed in the foreground on a blue armchair, wearing androgynous riding clothes, facing outward to the viewer. She extends her hand toward a female hyena, and the hyena imitates Carrington's posture and gesture, just as the artist's wild mane of hair echoes the coloring of the hyena's coat. Carrington frequently used the hyena as a surrogate for herself in her art and writing; she was apparently drawn to this animal's rebellious spirit and its ambiguous sexual characteristics. In the window in the background, a white horse (which may also symbolize the artist herself) gallops freely in a forest. A white rocking horse in a similar position appears to float on the wall behind the artist's head, a nod to the fairytales of the artist's early childhood. Carrington had been raised in an aristocratic household in the English countryside and often fought against the rigidity of her education and upbringing. This painting, with its doublings, its transformations, and its contrast between restriction and liberation, seems to allude to her dramatic break with her family at the time of her romance with Max Ernst. The distorted perspective, enigmatic narrative, and autobiographical symbolism of this painting demonstrate the artist's attempt to reimagine her own reality.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg)

Themes of transformation and metamorphosis were significant for Carrington, as was the concept of a feminine divinity with life-giving powers. This painting shows a monumental female figure in a red dress and a pale green cape towering over a forest of trees. Two geese appear to be emerging from beneath the figure's cape, and delicately painted animal figures and shapes are delineated on the Giantess's gown. The Giantess protects an egg, a universal symbol of new life, clasped in her hands, while geese circle clockwise around her and tiny figures and animals hunt and harvest in the foreground. The palette, scale, and facture of the painting demonstrate Carrington's interest in medieval and gothic imagery: the face of the Giantess resembles a Byzantine icon, painted flatly and illuminated with a gilded circle that frames her visage. The inclusion of geese may reflect her interest in Irish culture, in which this bird is a symbol of migration, travel, and homecoming. In a compositional technique reminiscent of Hieronymous Bosch, Carrington has included a host of strange figures that appear to be floating in the background. While the marine colors indicate that the ships and images are likely at sea, Carrington's hieratic method in this painting merges the sea and sky included in one image, emphasizing her interest in art's capacity to combine worlds.

Tempera on wood panel - Private Collection

Ulu's Pants

The hybrid characters that populate the labyrinthine world of Ulu's Pants reveal Carrington's nostalgia for the Celtic mythology she learned as a child, as well as her exposure to various cultural traditions during her time in Mexico. The disconcerting monstrous figures in the foreground are arranged in a static row, as if acting in a play. An egg, symbolic of fertility and rebirth, is guarded at the lower right by a strange figure with a red head. Carrington was deeply concerned with continuous renewal through self-discovery, an idea incarnated by shape-shifting figures in the foreground and by the distant creatures searching for a pathway through the maze in the background.

Oil and tempera on panel - Private Collection

Bird Bath

Later in her career, Carrington added portrayals of older women to her visual vocabulary of repeated settings and figures. The structure in the background of Bird Bath recalls her childhood home, Crookhey Hall, which was decorated with ornamental birds motifs. In the foreground, an elderly female figure dressed all in black (as Carrington herself dressed, in older age) sprays red paint onto a surprised-looking bird. The use of a large basin of water and a clean white cloth (held by the masked assistant) recalls the Christian sacrament of baptism, and the white bird may allude to the symbolic dove of the Holy Spirit. However, the ceremony enacted by these characters seems humorous as well as solemn. The woman in the scene has undergone her own transformation, from girl to crone, while retaining her creative power.

Color serigraph on paper - Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, California

Biography of Leonora Carrington

Childhood

Leonora Carrington was born in 1917 to Harold Carrington, an English, self-made textiles magnate, and his Irish-born wife, Maurie Moorhead Carrington. Carrington spent her childhood on the family estate in Lancashire, England. There she was surrounded by animals, especially horses, and she grew up listening to her Irish nanny's fairytales and stories from Celtic folklore, sources of symbolism that would later inspire her artwork. Carrington was a rebellious and disobedient child, educated by a succession of governesses, tutors, and nuns, and she was expelled from two convent schools for bad behavior.

Carrington was drawn to artistic expression over any other discipline; however, her parents were ambivalent concerning Carrington's artistic inclinations and they insisted on presenting her as a debutante at the court of King George V. When she continued to rebel, they sent her to study art briefly in Florence, Italy. Carrington was impressed by the medieval and Baroque sculpture and architecture she viewed there, and she was particularly inspired by Italian Renaissance painting. When she returned to London, Carrington's parents permitted her to study art, first at the Chelsea School of Art and then at the school founded by French expatriate and Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant.

Early Training

Fortuitously, Carrington was exposed to the work of leading avant-garde figures in her late teens, during the internationalization of the Surrealist movement. During her studies at Ozenfant's academy, she was deeply affected by two books. One was a travel memoir by Alexandra David-Néel, a female explorer who walked to Lhasa, Tibet, in the 1920s disguised as a man and became a lama. The other was Sir Herbert Read's Surrealism, with a cover illustration by the German artist Max Ernst. In 1936 the 19-year-old Carrington attended the International Exhibition of Surrealism at London's New Burlington Galleries, and found herself drawn to the Surrealists' mysterious artistic codes. Like many of the Surrealists, Carrington came from a privileged background that was simultaneously an impediment on creativity; feeling suffocated by the rigidity and class prejudices of the English aristocracy, she was attracted to the transformative potency of Surrealist aesthetics.

In 1937 Carrington met Max Ernst at a party in London. The two fell in love and departed for Paris. Ernst left his wife, and he and Carrington settled in Saint-Martin-d'Ardeche in southern France in 1938. During this phase of their romance, Carrington immersed herself in Surrealist practices, exploring collaborative processes of painting, collage, and automatic writing with Ernst. However, their idyll came to an end with the progression of World War II. Ernst was arrested several times in German-occupied France and eventually fled to the United States with the help of Peggy Guggenheim, abandoning his relationship with Carrington. Destroyed by her separation from Ernst, Carrington left France and traveled to Madrid, narrowly escaping the Nazis. In Spain she suffered a psychotic breakdown and was hospitalized in a mental hospital in Madrid. When she began suffering from repeated delusions and anxiety attacks, her parents intervened in her medical care. Carrington was institutionalized and treated with shock therapy. The artist was traumatized by this ordeal, and she eventually sought refuge in Lisbon's Mexican embassy.

Mature Period

With the encouragement of André Breton, Carrington wrote about her experiences with mental illness in her first novel, Down Below (1945), and created several haunting, dark paintings evoking her psychotic breakdown, including one also titled Down Below (1941). Carrington would often look back on this period of mental trauma as a source of inspiration for her art. In 1941 Carrington married the Mexican poet and diplomat Renato Leduc, a friend of Pablo Picasso. In their short-lived partnership, Carrington and Leduc traveled to New York before eventually requesting an amiable divorce.

Carrington settled in Mexico in 1942. In Mexico City, she met the Jewish Hungarian photographer Emeric ("Chiki") Weisz, whom she married and with whom she had two sons, Pablo and Gabriel. Carrington devoted herself to her artwork in the 1940s and 1950s, developing an intensely personal Surrealist sensibility that combined autobiographical and occult symbolism. She grew close with several other Surrealists then working in Mexico, including Remedios Varo and Benjamin Péret. In 1947 Carrington was invited to participate in an international exhibition of Surrealism at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York, where her work was immediately celebrated as visionary and uniquely feminine. Her work was also featured in group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery in New York.

Carrington's early fascination with mysticism and fantastical creatures continued to flourish in her paintings, prints, and works in other media, and she found kindred artistic spirits through her collaboration with the Surrealist theater group Poesia en Voz Alta and in her close friendship with Varo. Her continuing artistic development was enhanced by her exploration and study of thinkers like Carl Jung, the religious beliefs of Buddhism and the Kabbalah, and local Mexican folklore and mysticism.

Carrington was a prolific writer as well as a painter, publishing many articles and short stories during her decades in Mexico and the novel The Hearing Trumpet (1976). She also collaborated with other members of the avant-garde and with intellectuals such as writer Octavio Paz (for whom she created costumes for a play) and filmmaker Luis Buñuel. In 1960 Carrington was honored with a major retrospective of her work held at the Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno in Mexico City.

Late Period

From the 1990s onward, Carrington divided her time between her home in Mexico City and visits to New York and Chicago. During these late years, she began producing bronze sculptures of animals and human figures in addition to her paintings, prints, and drawings. She occasionally gave lively interviews about her life and career, from her early Surrealist experiments to her later artistic exploits. Carrington died on May 25, 2011, in Mexico City of complications due to pneumonia. She was 94 years old.

The Legacy of Leonora Carrington

Carrington played a significant role in the internationalization of Surrealism in the years following World War II, and she was a conduit of Surrealist theory in her personal letters and writings throughout her life, extending this tradition into the 21st century. Although her significant artistic output is frequently overshadowed by her early association with Ernst, Carrington's work has received more focused attention in recent years. Her visionary approach to painting and her intensely personal symbolism have most recently been reconsidered in the major retrospective exhibition 'The Celtic Surrealist' held at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in 2013. The relationship between Carrington's writing and her visual art is another subject of current interest. Lastly, feminist theory also plays a significant role in recent analysis of Carrington's art: Carrington's personal visual language of folklore, magic, and autobiography led the way for other female artists, such as Louise Bourgeois and Kiki Smith, who explored new ways to address female identity and physicality.

Influences and Connections