Summary of Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin is one of the most significant French artists to be initially schooled in Impressionism, but who broke away from its fascination with the everyday world to pioneer a new style of painting broadly referred to as Symbolism. As the Impressionist movement was culminating in the late 1880s, Gauguin experimented with new color theories and semi-decorative approaches to painting. He famously worked one summer in an intensely colorful style alongside Vincent Van Gogh in the south of France, before turning his back entirely on Western society. He had already abandoned a former life as a stockbroker by the time he began traveling regularly to the south Pacific in the early 1890s, where he developed a new style that married everyday observation with mystical symbolism, a style strongly influenced by the popular, so-called "primitive" arts of Africa, Asia, and French Polynesia. Gauguin's rejection of his European family, society, and the Paris art world for a life apart, in the land of the "Other," has come to serve as a romantic example of the artist-as-wandering-mystic.

Accomplishments

- After mastering Impressionist methods for depicting the optical experience of nature, Gauguin studied religious communities in rural Brittany and various landscapes in the Caribbean, while also educating himself in the latest French ideas on the subject of painting and color theory (the latter much influenced by recent scientific study into the various, unstable processes of visual perception). This background contributed to Gauguin's gradual development of a new kind of "synthetic" painting, one that functions as a symbolic, rather than a merely documentary, or mirror-like, reflection of reality.

- Seeking the kind of direct relationship to the natural world that he witnessed in various communities of French Polynesia and other non-western cultures, Gauguin treated his painting as a philosophical meditation on the ultimate meaning of human existence, as well as the possibility of religious fulfillment and answers on how to live closer to nature.

- Gauguin was one of the key participants during the last decades of the 19th century in a European cultural movement that has since come to be referred to as Primitivism. The term denotes the Western fascination for less industrially-developed cultures, and the romantic notion that non-Western people might be more genuinely spiritual, or closer in touch with elemental forces of the cosmos, than their comparatively "artificial" European and American counterparts.

- Once he had virtually abandoned his wife, his four children, and the entire art world of Europe, Gauguin's name and work became synonymous, as they remain to this day, with the idea of ultimate artistic freedom, or the complete liberation of the creative individual from one's original cultural moorings.

Important Art by Paul Gauguin

Still-Life with Fruit and Lemons

Composed while Gauguin was still working full time as a stockbroker and painting was little more than a hobby to him, this still-life reveals the artist's natural technical skill with brush and canvas. The subject matter is also standard Impressionist fare, and is a clear indicator of Gauguin's early influencers, which included Monet, Pissarro and Renoir. Gauguin's rendering of the tablecloth in particular also shows the strong influence of Cézanne, whose own still lifes used similar effects of outline and shading.

Oil on canvas - Museum Langmatt, Baden, Switzerland

Four Breton Girls

Unlike others who painted rural French subjects in the 1880s, Gauguin chose to depict four Breton girls in a field in no simple documentary, or realist manner. Much of the landscape visible in this work suggests Gauguin's roots in Impressionism and its attendant ideal to capture the visual dalliance of a landscape on the artist's eye, or retina. But Gauguin pushes that recent heritage to new purposes, placing the girls in dance-like formation; emphasizing the massive flow of their dresses; creating profiles and silhouettes of portraits and figures suggesting paper dolls...these and other artistic manipulations of the subject begin to serve a symbolic purpose, suggesting that deeper meanings are hidden behind the superficial appearances of reality. In this "synthetic" work, Gauguin thus fuses elements of visual accuracy with distortions of design and composition that speak of the girls' mystical union with nature; indeed, they collectively assume the formation of a grove of botanical specimens, a lively school of fishes, or a flock of birds in an unseen, overhead canopy. Faces, figures, clothing, and landscape each assume equal importance in this democratic arena, in which girls interlock their limbs as effortlessly as if they had originally grown that way.

Oil on canvas - Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

Self-Portrait 'Les Miserables'

Just prior to Gauguin's departure for Arles in late 1888, Gauguin and the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh sent each other examples of their respective work, including a number of self-portraits. This composition by Gauguin was included among the exchanges. In this work, Gauguin includes a likeness, in full profile, of the fictional character Jean Valjean, the morally upright but perpetually socially persecuted hero of Victor Hugo's Les Miserables (1862). Sporting a solemn look, tousled hair, and tired eyes, Gauguin clearly intends to draw a parallel between himself and Valjean, whose petty crime of the past (he once stole a loaf of bread) forever brands him a criminal, no matter of his subsequent virtues. Van Gogh later recalled being deeply impressed by Gauguin's uncommonly bold applications of color.

Oil on canvas - The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Vision After the Sermon (Jacob's Fight with the Angel)

Vision after the Sermon represents a significant departure from the subject matter of Impressionism, namely the city or rural landscape, which was still quite prevalent in Europe and the United States during the last two decades of the 19th century. Instead of choosing to paint pastoral landscape or urban entertainments, Gauguin depicted a rural Biblical scene of praying women envisioning Jacob wrestling with an angel. The decision to paint a religious subject was reminiscent of the Renaissance tradition, yet Gauguin rendered his subject in a decidedly modern style derived in part from Japanese prints, his own experiments in ceramics, stained-glass window methods, and other popular and "high art" traditions, finally emphasizing bold outlines and flat areas of color.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

The Yellow Christ

The Yellow Christ is a strong example of both Cloisonnism (a style characterized by dark contours and bright areas of color separated by bold outlines) and Symbolism (in which subject matter is idealized or romanticized in some fashion). The painting's predominant imagery, the crucified Christ, is evident, but Gauguin places the scene in the north of France during the peak season of Autumn foliage, indeed as women in 19th-century garb gather at the foot of the cross. It remains for the viewer to decide whether the vision is conjured in the minds of the pious or physically manifest in the contemporary landscape.

Oil on canvas - The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

Manao Tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch)

One of Gauguin's most famous works, Manao Tupapau is an excellent example of how Gauguin relished combining the ordinary with suggestions of the extraordinary in a single canvas, thus leaving all final interpretation open to debate. As he relates in a period diary, the actual scenario was inspired by his return home late one night and finding his wife, depicted here naked in the tropical heat, suddenly startled by his strike of a match in the all-enveloping darkness. Gauguin captures the luminous, unreal look of the sub-equatorial interior, here decorated by floral textiles, or batiks, along with other earthy materials, all suddenly illuminated by a momentary chemical combustion. At the same time, Gauguin introduces a ghostly depiction of a "watching" female spirit, seemingly harmless, at the foot of the bed, a direct reference to a local folklore describing how such spirits roam the night and forever share the world of the living.

This same painting also illustrates well how Gauguin remained forever a child of the 19th century, while nonetheless functioning as a bellwether, or beacon, to a younger generation. Most of his work remained rooted in the natural world around him, a legacy of his roots in Impressionism. But in some instances, Guaguin even speaks to the work of a former master, such as in this work, which for many eyes continues a precedent of the everyday, un-idealized nude set by Édouard Manet's Olympia (1863). Yet Gauguin's work finally suggests, like that of his even more Symbolist contemporaries Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau (both were more closely aligned than Gauguin with French Symbolist poetry of the day), that underneath the world of "rock solid" appearances lies a parallel realm of eternal mystery, spiritual import, and poetic suggestion.

Oil on canvas - The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

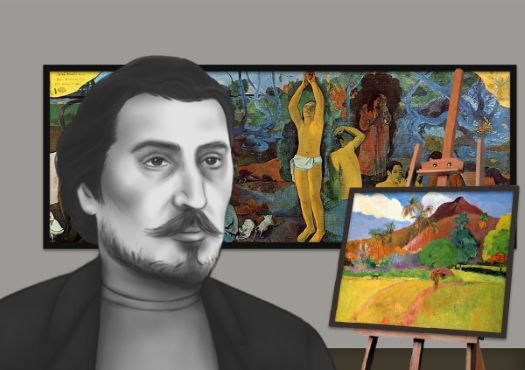

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

Gauguin's late-century magnum opus, painted in Tahiti, communicates a story in three stages from right to left, each stage corresponding to a question in the painting's title, which Gauguin inscribed, notably without question marks, in the upper left corner. The first stage of life, on the far right, is that of childhood; the second stage of young adulthood; the last stage of life's impending closure, here found at the far left, where, according to the artist, "an old woman approaching death appears reconciled and resigned to her thoughts." Unlike earlier attempts by Gauguin, this grand composition, derived partly from a long tradition of "stage-of-life" painting in Western societies, is not explicitly religious but, rather, more personal and obscurely spiritual. This is much in keeping with Gauguin's late-in-life retreat from European society into a culture native to what was then French Polynesia.

In employing such an evocative, yet oblique title, Gauguin alludes to his own increasingly philosophical and mystical tendencies of his mature years. He had always been linked by his contemporaries with a Symbolist movement in painting that was closely allied to French poetry of the 1880s and 90s, but rarely did he, himself, attach overtly philosophical or literary references to his canvases. In Where Do We Come From?, then, Gauguin is apparently looking back on a life spent largely apart from his own social and geographic wellsprings, and perhaps seeking mental, spiritual, and physical grounding in a world he consciously elected to serve as his "alternative reality."

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Two Tahitian Women

As Gauguin's time in Tahiti was coming to a close, he departed from his usual Symbolist style in order to paint portraits of Tahitian women, whose beauty, form, and lack of shame at their partial nudity (decidedly unlike many 19th-century European women's regard of the naked body) at once fascinated, attracted, and inspired him. This double portrait is typical of Gauguin's later work, much of which reflected the artist's deep love of nature. As learned from the benefit of hindsight, it should perhaps be noted that Gauguin's painterly vision of the islands was, in large measure, a romantic one, the place and its people in turn exoticized, sexualized, and otherwise exaggerated by a painter in search of a viable alternative to what he perceived to be Western society's own cultural shortcomings.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Biography of Paul Gauguin

Childhood

Paul Gauguin was born to Clovis Gauguin, a journalist, and Alina Maria Chazal, daughter of the socialist leader and early feminist activist Flora Tristan. At the age of three, Gauguin and his family fled Paris for Lima, Peru, a move motivated by France's tenuous political climate that prohibited freedom of the press. On the trans-Atlantic journey, Clovis fell ill and died. For the next four years, Gauguin, his sister, and mother lived with extended relatives in Lima.

In 1855, as France entered upon a more politically stable era, the surviving family returned to settle in the north-central French city of Orleans, where they lived with Gauguin's grandfather. There, Gauguin began his formal education and eventually joined the merchant marine (compulsory service) at age seventeen. Three years later Gauguin joined the French Navy. Returning to Paris in 1872, Gauguin took up work as a stockbroker.

Early Training

Following his mother's death in 1867, Gauguin went to live with his appointed guardian, Gustave Arosa, a wealthy art patron and collector. Under Arosa's care, Gauguin was introduced to the work of the Romantic painter, Eugene Delacroix, as well as the work of Realist painter Gustave Courbet, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and the pre-Impressionist, Barbizon school of French landscape painting. This education of the artist's eye in the work of his close predecessors was to have a lasting effect on Gauguin's later work.

Gauguin married Mette-Sophie Gad in 1873; subsequently, Gauguin, his Danish wife, and their five children moved from Paris to Copenhagen. Gauguin also began to collect art, procuring a modest array of Impressionist paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, and Camille Pissarro. By 1880 Gauguin was himself painting in his spare time and employing an Impressionist style, as in his Still-Life with Fruit and Lemons (1880). Gauguin also took to frequently visiting galleries, and eventually he rented his own artist's studio. In addition, Gauguin painted beside newly befriended artists Camille Pissarro and Paul Cézanne, and he himself participated in the official Impressionist exhibitions in Paris of 1881 and 1882.

Gauguin lost his job as a stockbroker in the financial crash of 1882; by 1885 he was seeking a new means of making a living. Plagued by bouts of depression, Gauguin finally decided to pursue his painting as an alternate career path. He returned to Paris determined to make a professional go of it, indeed, despite the fact that up to that time he entirely lacked formal artistic training. Meanwhile, Mette-Sophie and their children settled with extended family in Denmark. A several-month's stay in Brittany, at Pont-Aven, in mid 1886, proved a decisive turning point for Gauguin, who developed there a Symbolist style of painting in which flat, luminescent colors, like those of stained-glass windows, came to signify the local Breton peoples' natural and spiritual experience. During this trip and a subsequent sojourn in Brittany in 1889, Gauguin sought to achieve a new kind of "synthesis," or fusion of color, composition, and subject matter, not only from painting before a live model or landscape, such as in the manner of the Impressionists, but by bringing together numerous studies in a way that finally evoked the inner life of his subject over merely suggesting its outward appearance. In his Four Breton Girls (1886), for instance, naturalistic tones of landscape co-exist with larger expanses of pattern and color that begin to suggest a symbolic importance to the subject lying beyond what's immediately visible. Two years later, Gauguin sailed to Panama and, subsequently, Martinique, often living in a hut with friend and fellow artist Charles Laval. These travels to so-called primitive cultures; his observation of the natives in their own natural environment; and his own employment of a rich, vibrant palette would soon come to serve Gauguin as a foundation for an original artistic style.

Mature Period

By the late 1880s, Gauguin's work caught the attention of Vincent van Gogh, another young and gifted painter who, like Gauguin, frequently suffered from bouts of depression. Similarly to Gauguin's, van Gogh's painting - while distinctly Impressionistic - showed the potential to blossom into something entirely new. The two artists began a regular correspondence, during which they exchanged paintings, including self-portraits, among them Gauguin's Self-Portrait 'Les Miserables' (1888). In 1888, at van Gogh's invitation, the two men lived and worked together for nine weeks in van Gogh's rented house at Arles in the south of France. Van Gogh's brother and benefactor, Theo van Gogh, an art dealer by profession, served as Gauguin's primary business manager and artistic confident at the time.

During these nine weeks, both artists turned out an impressive number of canvases, among Gauguin's his now-famous Night Café at Arles (Mme Ginoux) and a signature early work, Vision After the Sermon (Jacob's Fight with the Angel) (both 1888). Neither man had a particularly promising reputation in the art world at this moment; rather, both were regarded as highly experimental painters searching for a new style that might depart from the mature Impressionism of Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro. The intensity of the artistic exchange would come to a dramatic conclusion as, by the end of nine weeks, van Gogh's depressive and occasionally violent emotional episodes led to the dissolution of their artistic partnership, although the two would forever admire each other's work.

Gauguin returned to Paris, but only briefly. By now completely uninterested with Impressionism and what had, by that time come to be referred to as Post-Impressionism, Gauguin focused on further developing his Symbolist flat application of paint and bold palette as in his painting The Yellow Christ (1889), a work largely influenced by Japanese prints, African folk art, and popular imagery imprinted on Gauguin's memory from his travels to South America and the French East Indies (today's Caribbean).

Late Period

In 1891, after spending years away from his wife and children, Gauguin effectively abandoned his family by moving alone, like a perpetual, solitary wanderer, to French Polynesia, where he would remain for the rest of his days. This move was the culmination of Gauguin's increasing desire to escape what he regarded as an artificial European culture for a life in a more "natural" condition.

In his final decade, Gauguin lived in Tahiti, and subsequently Punaauia, finally making his way to the Marquesas Islands. During this time he painted more traditional portraits, such as Tahitian Women on the Beach (1891), The Moon and the Earth (Hina tefatou) (1893), and Two Tahitian Women (1899). He also continued to experiment with quasi-religious and Symbolist subject matter, as in his Manao Tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch) (1892), and his Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897). These works were painted during a period in which Gauguin was essentially bidding his career adieu, as if he were an athlete "at the top of his game," so to speak, but wanting to aspire towards a more spiritual condition. Seeking an unworldly sense of repose and detachment, he is said to have been obsessed with his own mortality. He looked back on his life and even borrowed figures from his own earlier paintings, perhaps as though to symbolically lend them an extended lifespan. Notably, by 1899 Gauguin was referring to himself satirically, writing to a Paris colleague that he painted only "on Sundays and holidays," ironically like the amateur he once embodied prior to pursuing art seriously. Not long after that self-deprecating quip, he unsuccessfully attempted suicide by self-poisoning.

In early May, 1903, morally skittish, and weakened by drug-addiction and regular bouts with illness, Gauguin succumbed to the degenerative effects of syphilis and died at the age of 54, in the Marquesas islands, where he was subsequently buried.

The Legacy of Paul Gauguin

Gauguin's naturalistic forms and "primitive" subject matter would embolden an entire, younger generation of painters to move decisively away from late Impressionism and pursue more abstract, or poetically inclined subjects, some inspired by French Symbolist poetry, others derived from myth, ancient history, and non-Western cultural traditions for motifs with which they might refer to the more spiritual and supernatural aspects of human experience. Gauguin ultimately proved extremely influential to 20th-century modern art, in particular that of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque and their development of Cubism from about 1911 to 1915. Likewise, Gauguin's endorsement of bold color palettes would have a direct effect on the Fauvists, most notably André Derain and Henri Matisse, both of whom would frequently employ intensely resonant, emotionally expressive, and otherwise "un-realistic" color.

Gauguin, the man, became a legend almost independently of his art and came to inspire a number of literary works based on his "exotic" life story - a prime example being W. Somerset Maugham's The Moon and Sixpence (1919).

Influences and Connections

-

![Vincent van Gogh]() Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh -

![Émile Bernard]() Émile Bernard

Émile Bernard ![Theo van Gogh]() Theo van Gogh

Theo van Gogh![Charles Laval]() Charles Laval

Charles Laval![Emile Schuffenecker]() Emile Schuffenecker

Emile Schuffenecker

-

![Japonism]() Japonism

Japonism -

![Impressionism]() Impressionism

Impressionism -

![Historical African Art]() Historical African Art

Historical African Art ![Cloisonnism]() Cloisonnism

Cloisonnism

-

![Paul Cézanne]() Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne -

![Pablo Picasso]() Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso -

![Henri Matisse]() Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse -

![André Derain]() André Derain

André Derain ![Arthur Frank Mathews]() Arthur Frank Mathews

Arthur Frank Mathews

-

![Vincent van Gogh]() Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh -

![Ambroise Vollard]() Ambroise Vollard

Ambroise Vollard ![Charles Laval]() Charles Laval

Charles Laval

Useful Resources on Paul Gauguin

- Paul Gauguin: The Breakthrough Into ModernityOur PickBy Paul Gauguin, Agnieszka Juszczak, Heather Lemonedes, Belinda Thomson

- Gauguin: The Quest for ParadiseBy Francoise Cachin

- The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in ArlesOur PickBy Martin Gayford

- Paul GauguinOur PickBy David Sweetman

- Gauguin (Basis Art Series 2.0)Our PickBy Ingo F. Walther

- Gauguin: A Spiritual JourneyBy Christina Hellmich and Line Clausen Pedersen

- Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the SouthBy Douglas W. Druick et al.

- The Gauguin AtlasBy Nienke Denekamp

- Gauguin TahitiOur PickBy Paul Gauguin, George Shackelford, Claire Frèches-Thory

- Paul Gauguin: Artist of Myth and DreamOur PickBy Stephen Eisenman

- Gauguin: Maker of MythBy Belinda Thomson, Tamar Garb, Charles Forsdick, Vincent Gille, Linda Goddard, Philippe Dagen

- Gauguin and the Origins of SymbolismBy Richard Schiff, Richard R. Brettel, Guy Cogeval, Mary Ann Stevens, Lola Jiminez Blanco

- Delphi Complete Works of Paul Gauguin (Illustrated)Our PickBy Peter Russell

- The Sculpture and Ceramics of Paul GauguinBy Christopher Gray

- The Art of Paul GauguinOur PickBy Richard Brettell, Francoise Cachin, Claire Freches-Thory, and Charles F. Stuckey

- The Symbolism of Paul Gauguin: Erotica, Exotica, and the Great Dilemmas of HumanityOur PickBy Henri Dorra

- Paul Gauguin: The PrintsBy Elizabeth Prelinger and Tobia Bezzola

- Gauguin: PortraitsBy Cornelia Homburg and Christopher Riopelle