Summary of Lee Krasner

An ambitious and important artist in New York City during Abstract Expressionism's heyday, Lee Krasner's own career often was compromised by her role as supportive wife to Jackson Pollock, arguably the most significant postwar American painter, as well as by the male-dominated art world. Krasner was intimately involved in the synthesis of abstract form and psychological content, which announced the advent of Abstract Expressionism. Her desire to revise her aesthetic or what she called "breaks," led to her innovative Little Imageseries of the late 1940s, her bold collages of the 1950s, and, later, her large canvases, brilliant with color, of the 1960s. Krasner was "rediscovered" by feminist art historians during the 1970s and lived to see a greater recognition of her art and career, which continues to grow to this day.

Accomplishments

- Krasner was a key transitional figure within abstraction, who connected early-20th-century art with the new ideas of postwar America. Inspired by artist Piet Mondrian's "grid," Krasner helped devise the "all-over" technique, which in turn influenced Pollock's revolutionary "drip paintings."

- Krasner was remarkable for her artistic versatility and advanced skill, which, coupled with her intensive training in art theory, enabled her to revise her style and technique multiple times over the course of her career. Krasner purposefully initiated these "breaks" in order to distance herself from such artists as Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, whose work she found too "rigid" and repetitive, and also to express herself more fully.

- Krasner's incredibly high standards led her to cut up her older canvases that she found lacking. She recycled and reconfigured these scraps and pieces as collages, a practice that suggests that she was inspired by the work of Henri Matisse, whose work also inspired her colorful, decorative, large paintings of the 1960s. Because she reused her earlier canvases in this way, only a small body of Krasner's early work remains.

Important Art by Lee Krasner

Self Portrait

Painted in 1930 when she was just 22 years old, Self-Portrait illustrates Krasner's early traditional training in realism, her strong technical skill, and her self-assuredness in the role of an artist. Such training and control were the foundations from which her abstraction would take off, leading to her signature Little Image series of the late 1940s. Situated outdoors, which creates an air of 19th-century naturalism, Krasner painted Self-Portrait in order to advance as a student within the National Academy of Design. Krasner chose to paint herself in the garb of a working artist who confidently holds her paintbrushes firmly in hand. To capture her own reflection, she nailed a mirror to a tree and worked on the painting throughout the summer. Krasner has frozen the act of painting as she works on the canvas. Although initially her teachers under-appreciated Krasner and doubted the veracity of her painting outdoors, they did promote her into the life drawing class.

Oil on linen - The Jewish Museum, New York

Seated Nude

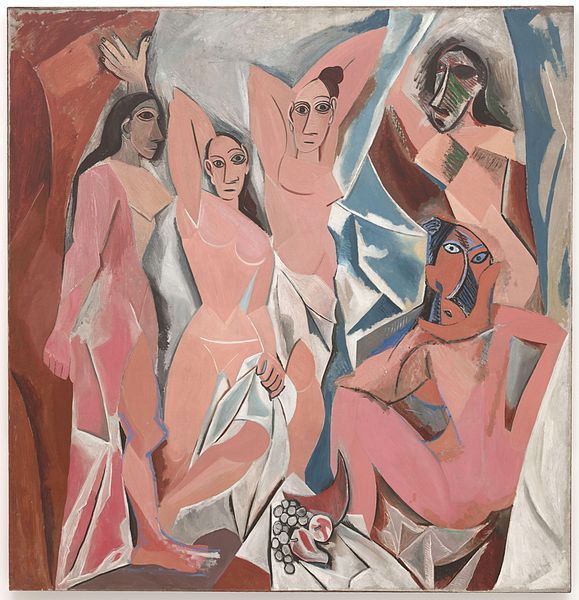

Showing her indebtedness to Picasso, Seated Nude displays Cubist elements such as Krasner's non-realist command of geometrical, cube-like forms and her experiments with space. The drawing's structure becomes the armature for Krasner's energetic and expressive application of line, a marker of the more pure abstractions to come. Her use of charcoal on paper gives the work a sense of immediacy and vibrancy rather than artistic finish. Her dark application of charcoal line, vigorously worked over the surface, testifies to her assured hand and growing talent.

Charcoal on paper - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Composition

During the mid to late 1940s, Krasner worked hard to undo her Cubist orientation and to more fully express her inner self. This work is part of the Little Image series of 31 paintings (1946-50) that represent her first all-over abstractions. With these paintings, Krasner expanded the visual vocabulary of Abstract Expressionism. Taking her start from Pollock, she worked more directly from instinct, but painted in a state of "controlled chaos." The series' title most likely came from her new small studio, out in the Springs, located in a small bedroom in the upstairs of the home she shared with Pollock; he commanded the large barn on their property. Krasner's painting demonstrates the expressive power of small, intricate lines and gestures as opposed to the mural-sized paintings of Newman and Pollock. This series was unique in her career since this was the only time she worked looking down on her canvas, dripping paint, rather than situated on an upright easel. Brightly colored with thickly textured surfaces, Krasner tightly controlled the drips she applied, which is evident in the white lines and drawings that cover the underlying support. The painting's overlapping skeins of white paint form tightly controlled small units that shimmer on the painting's surface. These small forms echo ancient picture-writing systems, and may relate to Jewish mysticism and the Kabalah. This deep connection to her inner-self and all-over covering of the canvas stand as key turning points in her career.

Oil on canvas - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Milkweed

Milkweed is an excellent example of an aesthetic "break" by Krasner and her subsequent turn to collage. Highly self-critical of her own work, in the early 1950s, Krasner started to rip and shred early paintings which did not meet her standards. Milkweeds was conceived by Krasner by recycling some of these remenents, which she incoporates with paper scraps and by applying a new layer of oil paint. The title was chosen once she had finished the work, and was most likely named after the stem and leaf-shapes of the common milkweed plant and the orange and black monarch butterfly which deposits its eggs on the milkweed. With these collages, Krasner introduces the natural world - a long interest of hers - into her aesthetic and also broadens the vocabulary of the greater Abstract Expressionist movement.

Oil, paper and canvas collage on canvas - Albright-Knox Museum

Cool White

Krasner's Cool White demonstrates how she could exploit a limited color palette of somber umber tones and white to its maximum effect through her dynamic use of form and brushwork. Krasner aggressively applied paint from a thickly loaded brush, dragging and pushing the pigment all over to create an energetic, pulsating image. The limited colors and tones do not limit the work's impact in any way, and in fact, draw attention to Krasner's powerful forms and assertive brushstrokes.

After Pollock's death, Krasner worked in his studio in the barn, which permitted her to work on a larger scale and with greater, sweeping gestures. Krasner created Cool White during the difficult time after Pollock's sudden death, during which she was dealing with the increasing demands of his estate and the abrupt cancelation of an exhibition organized by Clement Greenberg. Of this and similar works of the late-1950s, Krasner explained their autobiographical origins: "I painted a great number of them because I couldn't sleep nights. I got tired of fighting insomnia and tried to paint instead. And I realized that if I was going to work at night I would have to knock out color altogether, because I couldn't deal with color except in daylight." Cool White stands as Krasner's own interpretation of large scale, broad-gestured, intuitive painting for which Pollock is better known.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery of Australia

Gaea

Krasner's signature vibrant use of color, lifelong interest in the fecundity of nature, and joyous sensibility were among her key contributions to the often brooding, deeply serious post-war abstract tendencies of her peers. Via her paintings, Krasner worked through her profound anguish and anger after Jackson Pollock's death. Later, she turned to nature to create large-scale, brilliantly colored canvases that show the influence of Henri Matisse and the Fauvists, again demonstrating her connection to early-20th-century modernism. Inspired by the natural world, Krasner painted large, floral, and organic shapes, alive with color and pulsating with new energy. The piece's title refers to the Mother Earth goddess of Greek mythology, representative of her continued interest in ancient civilizations as artistic sources. Her creative output of the 1960s expresses a sense of rebirth and elation after her emotional trauma and struggles of the prior decades.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Mysteries

Here, Krasner's use of rich unsaturated colors, hard-edged organic forms, and palette of white, red, and black displays the influence of Northwest coast art, especially wood carving by such peoples as the Haida, the Tlingit, and the Kwakiutl. In 1941, MoMA exhibited a major show of Native American art, which greatly excited several abstract painters including Lee Krasner and Barnett Newman. Inspired by Carl Jung's theories of a collective unconscious, Native art was seen as especially relevant to modern art and life through its formal complexity and mythological basis.

Oil on cotton duck - The Brooklyn Museum of Art

Biography of Lee Krasner

Childhood

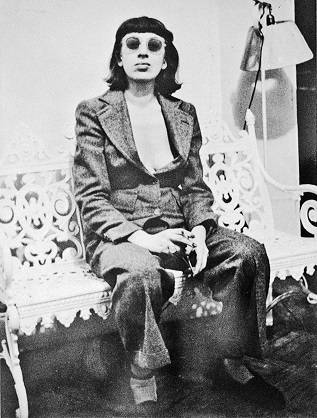

Lee Krasner was the sixth of seven children born to Russian-Jewish immigrants on October 27, 1908, who emigrated from Bessarabia. Growing up in immigrant, Jewish neighborhoods in Brooklyn, New York, Krasner was born Lena Krassner, but changed her name several times in the early portion of her life, eventually settling on Lee Krasner by the late 1940s. Art historians have pondered if Krasner used the abbreviated "Lee" as an attempt to disguise her gender.

By the young age of 13, Krasner had already set her sights on becoming a professional artist, which was an unusual career choice for an immigrant and a woman. She eagerly applied to and was pleased to be accepted by Washington Irving High School, the only New York City public high school at the time that allowed women to study art.

Early Training

As an adult, Krasner remained in New York City, which was developing into an international art center, enrolling first at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Art and Science in 1926, and then at the Art Students League. While a student at the prestigious National Academy of Design from 1926 through 1928, her conservative teachers often chastised her original, independent streak, which they deemed unsuitable for a woman. During this period, Krasner's work impressively ranged from realistic self-portraiture to surrealist experimentation.

Krasner had to work in a factory, as a waitress, and also as an artist's model while studying for her teaching certification at night - the then approved career-path for women artists. In 1933, she was lucky to obtain full-time work as an artist through the Works Progress Administration of the Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP), a visual arts program within Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal (1933-43). Many artists were kept financially afloat thanks to the New Deal programs, which also offered them camaraderie. The New Deal projects provided essential financial support to women artists, many of whom were provided their first professional opportunities under its auspices. Having quickly advanced to a supervisory position, Krasner also worked as an assistant on large-scale public murals; in turn, Pollock served as her assistant on other WPA murals.

Unhappy with the conservative artistic approach that she had learned earlier at the National Academy, Krasner fell into more bohemian art circles during the 1930s and, like many of her artistic peers, was drawn to Marxism. Her choice to study under the leading artist and theorist Hans Hofmann proved significant since he exposed the young artist to the work and theories of Cubist painter and sculptor Pablo Picasso, as well as the modernist Henri Matisse. Under the tutelage of Hofmann, Krasner began to work in an "all-over" style, covering the surfaces of her paintings with abstract, repetitive designs informed by floral motifs. Hofmann once offered her the backhanded compliment that her work was so good "you would not know it was made by a woman artist."

Mature Period

Krasner became a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, a group formed in New York City in 1936 to promote and help the public appreciate abstract art. It was then that she met Pollock, moving in with him in 1941. The pair married in 1945, and the duties of promoting and managing the practical aspects of Pollock's career fell to her. While Krasner generously embraced her new responsibilities, it meant her own career took a back seat to the increasingly famous Pollock.

Krasner never stopped creating during her 11-year marriage to Pollock. Throughout their time together, Krasner struggled with his pronounced alcoholism and womanizing. When the couple relocated from Manhattan to the Springs, Long Island, in the late 1940s, and Krasner began her breakthrough Little Imageseries (1946-50), a body of work defined by the small size of the paintings and their repetitive, linear designs often in white pigment. Along with Newman, Krasner shared an interest in Jewish Mysticism, or Kabalah, which comes to light in these small canvases. Her traditional Jewish education and heritage shaped the process and look of this series in which she intuitively painted right to left, or the direction of Hebrew lettering and created Kabalistic symbols, in order to directly connect with her subconscious. Many modernists looked to other cultures, such as non-Western and tribal groups, for their artistic inspirations, whereas Krasner in fact was returning to her own cultural origins.

Krasner possessed a lifelong admiration of Matisse's work, and in the early 1950s began to experiment with collage, a technique that Matisse used late in his career. After a particularly frustrating day in the studio Krasner impetuously tore up her finished paintings, which she then later reassembled into constructions reminiscent of Cubism. Krasner's 1955 exhibition of these works was positively received, prompting well-known and demanding critic Clement Greenberg to declare it one of the most important shows of the decade.

The following year, Krasner began a large-scale Abstract Expressionist series called Earth Green, (1956-59) after her husband's death in a fatal car accident. Critics responded negatively to these works, which combined nature-inspired forms with a rhythmic, splattered technique, because they believed that the work was both derivative of Pollock's and too decorative (a codeword for too feminine). In 1962, Krasner suffered an aneurism, which sidelined her artistic productivity for several years afterward due to ill health. In the following period, Krasner continued to work with her nature-forms in variety of ways, combining them with large areas of more solid color on her canvases (a choice inspired by Color Field Painting and Minimalism). In the late 1960s and 1970s, her work experienced a revival due to the women's movement.

Late Years and Death

Krasner's experimental techniques and innovative use of color and scale were finally recognized in her first retrospective exhibition in October 1983 at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts in Texas. Despite her poor health, Krasner was able to attend the exhibition, which subsequently traveled to San Francisco, California, Phoenix, Arizona, and Norfolk, Virginia. Unfortunately, Krasner died in June 1984 from internal bleeding due to diverticulitis and was never able to see her retrospective make its final stop at New York's eminent Museum of Modern Art.

The Legacy of Lee Krasner

Krasner's artwork and biography continue to inspire generations of painters and she has become revered especially amongst women artists. Throughout her career, she directly confronted the dominant stereotype that "women can't paint" and struggled within the Abstract Expressionist movement, which prized masculinity and heroic figures such as Pollock. Krasner influenced other artists, including those from future generations, by her stylistic and artistic innovations, her example of persistence, and her ultimate triumph. During the 1960s, her large-scale brightly-colored works encouraged the feminist artist Miriam Schapiro's femmage works. It was after Krasner's death, thanks to her generosity, that the Pollock-Krasner Foundation was established with the goal of assisting the development of fine artists. Since its creation in 1985, the foundation has awarded over 46 million dollars in grants to working artists around the world. Now affiliated with the State University at Stony Brook, New York, the Pollock-Krasner House in East Hampton, New York, has been kept as it was when the artistic couple lived and worked there and is open to the public for visitation.

Influences and Connections

-

![Clement Greenberg]() Clement Greenberg

Clement Greenberg -

![Jackson Pollock]() Jackson Pollock

Jackson Pollock -

![Harold Rosenberg]() Harold Rosenberg

Harold Rosenberg ![Barbara Rose]() Barbara Rose

Barbara Rose

Useful Resources on Lee Krasner

- Lee KrasnerOur PickBy Robert Carleton Hobbs, Lee Krasner

- Lee KrasnerOur PickBy Gail Levin

- Jackson Pollock and Lee KrasnerBy Ines Janet Engelmann

- Lee Krasner: A RetrospectiveBy Barbara Rose, Lee Krasner

- Lee Krasner, CollagesBy Bryan Robertson, Robert Hughes

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI