Summary of René Magritte

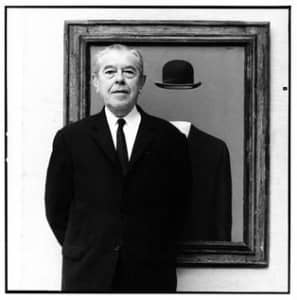

Surely the most celebrated Belgian artist of the 20th century, René Magritte has achieved great popular acclaim for his idiosyncratic approach to Surrealism. To support himself he spent many years working as a commercial artist, producing advertising and book designs, and this most likely shaped his fine art, which often has the abbreviated impact of an advertisement. While some French Surrealists led ostentatious lives, Magritte preferred the quiet anonymity of a middle-class existence, a life symbolized by the bowler-hatted men that often populate his pictures. In later years, he was castigated by his peers for some of his strategies (such as his tendency to produce multiple copies of his pictures), yet since his death his reputation has only improved. Conceptual artists have admired his use of text in images, and painters in the 1980s admired the provocative kitsch of some of his later work.

Accomplishments

- Magritte wished to cultivate an approach that avoided the stylistic distractions of most modern painting. While some French Surrealists experimented with new techniques, Magritte settled on a deadpan, illustrative technique that clearly articulated the content of his pictures. Repetition was an important strategy for Magritte, informing not only his handling of motifs within individual pictures, but also encouraging him to produce multiple copies of some of his greatest works. His interest in the idea may have come in part from Freudian psychoanalysis, for which repetition is a sign of trauma. But his work in commercial art may have also played a role in prompting him to question the conventional modernist belief in the unique, original work of art.

- The illustrative quality of Magritte's pictures often results in a powerful paradox: images that are beautiful in their clarity and simplicity, but which also provoke unsettling thoughts. They seem to declare that they hide no mystery, and yet they are also marvelously strange. As Magritte biographer David Sylvester brilliantly described, his paintings induce "the sort of awe felt in an eclipse."

- Magritte was fascinated by the interactions of textual and visual signs, and some of his most famous pictures employ both words and images. While those pictures often share the air of mystery that characterizes much of his Surrealist work, they often seem motivated more by a spirit of rational enquiry - and wonder - at the misunderstandings that can lurk in language.

- The men in bowler hats that often appear in Magritte's pictures can be interpreted as self-portraits. Portrayals of the artist's wife, Georgette, are also common in his work, as are glimpses of the couple's modest Brussels apartment. Although this might suggest autobiographical content in Magritte's pictures, it more likely points to the commonplace sources of his inspiration. It is as if he believed that we need not look far for the mysterious, since it lurks everywhere in the most conventional of lives.

The Life of René Magritte

A “splendid misapprehension,” was how Magritte described his waking from a dream when, looking at the birdcage in his room, he saw an egg, instead of the bird, in the cage. Out of the experience he began altering ordinary objects, transforming them into paintings that “challenge the real world.”

Important Art by René Magritte

Bather

This elegant work is a fine example of Magritte's early attempts to find a restrained, illustrative style. It bears comparison with contemporary Belgian Expressionism and also with the classicizing modernist styles that were then popular throughout Europe. We can recognize many of the elements that characterized his later paintings, such as the prominence of the sea and the mysterious sphere in the background. This work also bears the influence of Magritte's professional forays into the world of fashion advertising, and his interest in the works of Fernand Léger. Bather can be compared to his painting The Bather between Light and Darkness (1935-36), which explores the same scene in the artist's mature style. In 1930, the artist gifted the picture to his sister-in-law, Leontine Berger.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Familiar Objects

Here, the viewer is confronted by five men - or perhaps five views of the same man - each corresponding to a seemingly random object. These bland portraits with indistinct clothes, features, and expressions are characteristic of Magritte. The objects, on the other hand, are unique and command more attention than the figures who stare blankly at them. Several pictures that predate this attest to Magritte's interest in depicting objects in his work, but this is the first in which the objects appear alongside figures and are associated with the mental states of those figures. In this regard it shows the artist's growing interest in the Surrealist idea of the unconscious. Magritte's way of placing the objects in relation to the figures also enabled him to partially occlude their faces, a strategy which he would often employ in later work.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

The Treachery of Images

The Treachery of Images cleverly highlights the gap between language and meaning. Magritte combined the words and image in such a fashion that he forces us to question the importance of the sentence and the word. "Pipe," for instance, is no more an actual pipe than a picture of a pipe can be smoked. Magritte likely borrowed the pipe motif from Le Corbusier's book Vers une architecture (1923), since he was an admirer of the architect and painter, but he may also have been inspired by a comical sign he knew in an art gallery, which read, "Ceci n'est pas de l'Art." The painting is the subject of a famous book-length analysis by Michel Foucault. One might also compare it with Joseph Kosuth's handling of a similar problem of image, text, and reality in his 1965 installation One and Three Chairs.

Oil on canvas - Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Ocean

The bright colors and casual brushwork of The Ocean typifies a series of satirical pictures Magritte painted in the style of late Pierre-Auguste Renoir, whose pictures were intended to mock the conservative tastes of the French public. The pose of the river god in this picture borrows directly from a late work by Renoir. As the Second World War drew to a close, he turned away from the more macabre subjects of Surrealism and embraced a radiant palette and, as he put it, "bewitching subjects." The artist wrote that he wanted to paint pictures "that will arouse what remains of our instinct for pleasure." Three years later in 1946, he signed the manifesto Surrealism in Full Sunlight that his Belgian friends had written to outline such principles. But the pictures in this style attracted considerable criticism from his Surrealist friends.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

The Pebble

The Pebble was included in Magritte's first Paris exhibition in 1948, where he shocked critics and public alike with an uncharacteristic group of his "vache" works. This group of around thirty pictures was painted rapidly in only a few weeks. It borrowed from the sketchy style of comics and caricatures, but some elements were also derived from Édouard Manet and Fauvism (the background in this picture may come from Henri Matisse). It also borrows the Venus de Milo motif that Magritte had used before. Perhaps unfortunately for the artist, the exhibition achieved its perverse effect, and was both financially and critically devastating to him. However, he remained attached to the work, and later gave this piece to his wife.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Empire of Light

The Empire of Light exemplifies the sort of simple paradox that characterizes Magritte's most successful works. Dusk has fallen in the bottom half of the picture and a streetlamp glows peacefully. Above, cheerful white clouds hang in a baby-blue sky. Although both elements of night and day are calming and lovely considered on their own, their juxtaposition is eerie and unnerving. As Magritte once said of Max Ernst's and Giorgio de Chirico's work, the darker statement similarly applies to strains of Magritte's own work: "the spectator might recognize his own isolation and hear the silence of the world." The overall impression of this scene is one that powerfully stays in the mind of the viewer.

Overall, Magritte's rather 'straightforward' rendition of the uncanny - one that resembles reportage in its simplicity - certainly owes something to the artist's experience working in commercial art. The style, and the handling of the paint - restrained and illustrative - may also have been inspired by the emphasis on clarity and impact in commercial art.

Oil on canvas - The Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

Biography of René Magritte

Childhood

René Magritte was the eldest of three boys, born to a fairly well-off family. His father is thought to have been in the manufacturing industry, and his mother was known to be a milliner before her marriage. Magritte's development as an artist was influenced by two significant events in his childhood; the first was an encounter with an artist painting in a cemetery, who he happened across while playing with a companion. Magritte later wrote, "I found, in the middle of some broken stone columns and heaped-up leaves, a painter who had come from the capital, and who seemed to me to be performing magic." The second pivotal event was the suicide of his mother in 1912 when Magritte was 14. According to the apocryphal account, Magritte was present when her body was fished out of a river, her face covered completely by her white dress. While current scholars believe this to be no more than a myth propagated by his nurse, the image of a head uncannily concealed by a contour-hugging cloth reoccurs throughout the artist's oeuvre.

Early Training

Magritte first began to paint in 1915 and enrolled in the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Brussels the following year. However, he was fairly uninspired by his classes, and his attendance suffered as a result. He did become close friends with a fellow student, Victor Servranckx, who introduced Magritte to Futurism, Cubism, and Purism. In particular, Magritte was drawn to the work of Jean Metzinger and Fernand Leger, both of whom had much influence on Magritte's early work, as is evident from his experiments with Cubism such as his 1925 piece Bather.

Mature Period

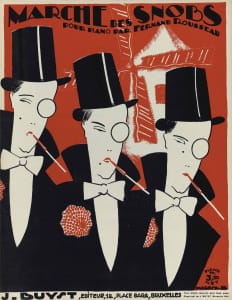

In 1921, Magritte performed his obligatory military service and returned home in 1922 to marry Georgette Berger, a girl he had known since childhood. He also began work under Servranckx's supervision as a draughtsman in a wallpaper factory. This job lasted about a year, after which Magritte became a freelance designer of posters and publicity. In 1926, he signed a contract with the Galerie le Centaure in Brussels and was able to make his living as a fine artist for a brief spell. This early period was marked by profound changes in Magritte's work. Around 1925 he first saw the work of Giorgio de Chirico and began to work more distinctly within the Surrealist idiom. Not only were Magritte's images from the mid-1920s reminiscent of the desolate and mysterious mood that de Chirico created in his work, but the younger artist also went so far as to actually transpose many of de Chirico's favorite objects such as spheres, trains, and plaster hands onto his own canvases.

From 1927 to 1930, Magritte lived in Paris and forged strong connections with André Breton's coterie of Parisian Surrealists that at that time included artists such as Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí. He began incorporating more ambiguously organic forms in his work and experimenting with quintessentially Surrealist subject matter such as madness and hysteria. However, Magritte was increasingly disillusioned by the "dark" subjects of his fellow Surrealists. Perhaps most significantly, it was in Paris that Magritte began to experiment with the use of words and language in his paintings.

By 1930, his contract with the Galerie le Centaure had ended, and, later that year, the gallery shut its doors altogether. Magritte returned to Brussels to take up work in commercial advertising once again. Scholars dispute whether Magritte also supplemented his income during this time by producing faked paintings of established artists and even perhaps forged currency. Regardless, from 1930 to 1937, Magritte had little time to devote to his own art. By the late 1930s however, the growing interest of international collectors, including Edward James in London, led to Magritte's increased financial independence, and he was at last able to give up commercial work almost completely.

Late Period

Just as Magritte was achieving success and recognition, the Second World War broke out. Although he continued to develop his signature style, he also increasingly deployed a bright, impressionistic palette as a subversive response to the bleakness of the war. He wrote, "The sense of chaos, of panic, which Surrealism hoped to foster so that everything might be called into question was achieved much more successfully by those idiots the Nazis... Against widespread pessimism, I now propose a search for joy and pleasure." In 1946, Magritte signed a manifesto called Surrealism in Full Sunlight, and broke with Breton. This phase was followed by Magritte's brief experiment with an intentionally provocative "savage" style he called "vache" ("cow") that was characterized by vulgar subjects, crude coloring, and is generally regarded as parodying the Fauves. As Magritte expected, his works in this style were phenomenally unpopular. For the remainder of the 1950s and '60s, Magritte returned to his characteristic style and set of subjects. By the end of his life, he enjoyed great success and there were six major retrospectives of his oeuvre in the 1960s alone.

The Legacy of René Magritte

Magritte's work had a major impact on a number of movements that followed his death, including Pop, Conceptualism, and the painting of the 1980s. In particular, his work was hailed as a harbinger of upcoming trends in art for its emphasis on concept over execution, its close association with commercial art, and its focus on everyday objects that were often repeated in pictorial space. It is easy to see why artists such as Andy Warhol, Martin Kippenberger, and Robert Gober cite Magritte as a profound influence.

Influences and Connections

-

![Paul Eluard]() Paul Eluard

Paul Eluard ![Edward James]() Edward James

Edward James

![Paul-Gustave van Hecke]() Paul-Gustave van Hecke

Paul-Gustave van Hecke![E. L. T. Mesens]() E. L. T. Mesens

E. L. T. Mesens![Paul Nouge]() Paul Nouge

Paul Nouge

-

![Pop Art]() Pop Art

Pop Art -

![Conceptual Art]() Conceptual Art

Conceptual Art ![Appropriation Art]() Appropriation Art

Appropriation Art

Useful Resources on René Magritte

- MagritteOur PickBy Suzi Gablik

- Magritte: Attempting the ImpossibleBy Siegfried Gohr, René Magritte

- Keeping an Eye Open - Magritte: Bird into EggOur PickBy Julian Barnes / One chapter devoted the originality of Magritte