Summary of Alexander Rodchenko

Alexander Rodchenko is perhaps the most important avant-garde artist to have put his art in the service of political revolution. In this regard, his career is a model of the clash between modern art and radical politics. He emerged as a fairly conventional painter, but his encounters with Russian Futurists propelled him to become an influential founder of the Constructivist movement. And his commitment to the Russian Revolution subsequently encouraged him to abandon first painting and then fine art in its entirety, and to instead put his skills in the service of industry and the state, designing everything from advertisements to book covers. His life's work was a ceaseless experiment with an extraordinary array of media, from painting and sculpture to graphic design and photography. Later in his career, however, the increasingly repressive policies targeted against modern artists in Russia led him to return to painting.

Accomplishments

- Rodchenko's art and thought moved extremely rapidly in the 1910s. He began as an aesthete, inspired by Art Nouveau artists such as Aubrey Beardsley. He later became a Futurist. He digested the work of Vladimir Tatlin, and the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich. By the decade's end he was pioneering Constructivism. This experimental inquiry into the elements of pictorial and sculptural art produced purely abstract artworks that separate out the components of each image - line, form, space, color, surface, texture, and the work's physical support. Constructivism encouraged a new focus on the tangible and material aspects of art, and its experimental spirit was encouraged by a belief that art had to match the revolutionary transformations then taking place in Russian politics and society.

- Rodchenko's commitment to the values of the Revolution encouraged him to abandon painting in 1921. He embraced a more functional view of art and of the artist, and he began collaborating with the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky on a series of advertising campaigns. Their work not only introduced modern design into Russian advertising, but it attempted to sell the values of the Revolution along with the products being promoted. This particular union of modern design, politics, and commerce has occasionally inspired advertisers in the West since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

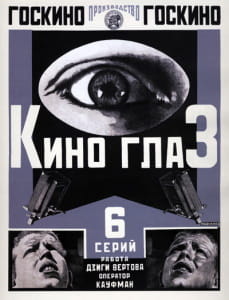

- Photography was important to Rodchenko in the 1920s in his attempt to find new media more appropriate to his goal of serving the revolution. He first viewed it as a source of preexisting imagery, using it in montages of pictures and text, but later he began to take pictures himself and evolved an aesthetic of unconventional angles, abruptly cropped compositions, and stark contrasts of light and shadow. His work in both photomontage and photography ultimately made an important contribution to European photography in the 1920s.

The Life of Alexander Rodchenko

Though he came from working-class roots, Russian artist Alexander Rodchenko soon connected with avant-garde artists and intellectuals of the early twentieth century, found himself actively engaged in the Bolshevik Revolution, and developed a philosophy of art as a powerful tool of social and political change which he sought to uphold throughout the Lenin years.

Important Art by Alexander Rodchenko

Dance. An Objectless Composition

Rodchenko attended a lecture by Russian Futurists Wassily Kamensky, David Burliuk, and Vladimir Mayakovsky, in Kazan in 1912, and was immediately converted. He abandoned the Art Nouveau styling of some of his earlier work and began to fragment his forms to create dynamic compositions. Dance is perhaps his most Futurist painting, and it clearly resembles works by Italian Futurists such as Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini. However, Rodchenko soon grew disinterested in the style and, following this, he began to create even more abstract pictures, putting aside entirely the last suggestions of illusion that Dance creates.

Oil on canvas - The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Non-Objective Painting No 80 (Black on Black)

Rodchenko was powerfully influenced by Kazimir Malevich's Suprematism, and particularly by works such as Black Square (1915), which reduced the components of the painting to a single black square that echoed the shape of the canvas. However, Rodchenko rejected the older man's spiritualism and strove instead to emphasize the material qualities of painting, in particular surface and texture (or "faktura" as the Russians called it). Non-Objective Painting No 80 is typical of this phase in his career and is part of a series of similar "Black on Black" paintings, which were exhibited alongside five white paintings by Malevich in Moscow in 1919. The exhibition was important in catapulting Rodchenko into the forefront of Russia's avant-garde.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Construction No. 127 (Two Circles)

By 1920, Rodchenko no longer felt obliged to imbue his basic geometric figures with distinguishable layers of color. In this composition, two perfectly drawn circles intersect. The white circles on black canvas form a powerful juxtaposition liberating the line from any recognizable connotations. This balanced and precise geometric composition underlines Rodchenko's preoccupation with engineering and design that he maintained throughout his career. Rodchenko arrived at compositions such as these by progressively stripping away all that he considered unnecessary in the field of painting; after reducing color to black and emphasizing surface texture, he seized on line as the most important and elemental component of the medium. This development may have been influenced by Wassily Kandinsky's ideas, since the two artists were closely associated, though while Kandinsky stressed the expressive possibilities of line, Rodchenko emphasized its possibilities as a tool of construction.

Oil on canvas - The Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Pure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, Pure Blue Color

Here Rodchenko reinterprets the iconic art form of the Western tradition - the triptych - which was traditionally reserved for the representation of religious scenes. The piece reflects Rodchenko's interest in Malevich throughout these years, but instead of pursuing Malevich's spiritualism, he stressed the physical, material properties of painting - in this case, color. Rodchenko regarded these pictures as his final statement on painting, famously writing, "I reduced painting to its logical conclusion and exhibited three canvases: red, blue and yellow. I affirmed: it's all over. Basic Colors. Every plane is a plane and there is to be no representation." These monochrome experiments have been a crucial example for later generations of abstract artists, particularly Minimalists.

Oil on canvas - Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova Archive, Moscow

Maquette for the Advertisement of the Red October Bisquittes

When Rodchenko abandoned painting in 1921, he also abandoned many of the traditional attitudes of the artist as a commentator on society and began instead to put his talents in the service of the Russian industry and the nascent revolution. This is an early example of his work for Russian industry, advertising Red October confectionary. Rigid geometry defines the composition through the juxtaposition of horizontal and vertical lines. The letters themselves are stylized. Both whimsical and visually arresting, Rodchenko's designs were an important influence on such key artistic laboratories as the Bauhaus in the Weimar Republic.

Gouache on paper - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Books (The Advertisement Poster for the Lengiz Publishing House)

This poster arguably brought Rodchenko the most fame and appreciation from his patrons in the Soviet government. The composition is typical of his use of photomontage in the period (the combination of photography and text). And it also reflects the ways in which he updated Russian advertising, using geometric compositions and strident colors to trumpet modernity. While his designs are directed at promoting individual companies or products, they also - often explicitly - endorse the goals of political revolution.

Photomontage and Gouache on Paper - Private Collection

The Staircase

This is one of Rodchenko's finest photographs. Often credited with devising the key principles of modern photography, Rodchenko is praised for his use of unusual angles and perspective. Here, he juxtaposes the motif of a woman with a child against the stern geometry of the man-made environment. The position of the camera at a peculiar angle provides for an innovative, yet carefully balanced and flowing composition. Compositions such as this were an important influence on New Vision, the modernist photography movement that gripped Europe in the 1920s and '30s.

Gelatin-silver print - Private Collection

Biography of Alexander Rodchenko

Childhood

Alexander Rodchenko was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, to a working class family. His father, Mikhail Rodchenko, was a theater props manager and his mother, Olga, a washerwoman. The family's social status did not provide much opportunity for the artistic education of talented Alexander. It is still unclear what training (if any) Rodchenko might have acquired as a child. The family moved to the city of Kazan in 1905. Two years later, Mikhail passed away, but they were able to allocate some of the family's scarce funds for Alexander's education.

Early Training

Rodchenko enrolled in the Kazan School of Art, where he studied from 1910 to 1914 under Nikolai Feshin and Georgii Medvedev. The young artist quickly absorbed the basic principles of the academic training, earning high praise from his instructors. In 1914, he met Varvara Stepanova, a fellow student. They became life-long partners and artistic collaborators.

Kazan proved to be too small and stifling for Rodchenko's emerging vision. He and Stepanova journeyed to Moscow in 1915 to acquire more meaningful exposure to the nascent Russian modernism, permanently settling there in 1916. Rodchenko attended the Stroganov Institute, where he studied drawing, painting, and art history.

In Moscow, Rodchenko was influenced by the key figures of the Russian avant-garde movement, namely Vladimir Tatlin and Kazimir Malevich. He executed his first abstract drawing, reminiscent of Malevich's Suprematist compositions, in 1915. But it was not only the avant-garde artistic milieu that influenced him. Through his acquaintances with liberal thinkers such as the Futurists David Burliuk and Vasily Kamensky, Rodchenko found himself in the heart of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

Rodchenko's involvement with the Bolshevik cause was both ideological and aesthetic. As a working class young man, he witnessed firsthand the social injustice of Tsarist Russia. Rodchenko deeply believed in the power of art as a driving force of social transformation, as is detailed in many of his letters and diaries, which were only recently translated into English. Rodchenko embraced the emerging aesthetics of Russian Constructivism, becoming a leading member of the group.

Rodchenko's early years demonstrated his artistic talent and quest for innovation. From 1917 to 1918, he was mainly experimenting with flat geometric compositions. Then, in 1919, he created an entirely abstract series of Black on Black paintings, which might be read as a response to the spiritualism of Malevich's Black Square (1915). While Malevich's work seemed to herald the end of painting, it also touted a spiritualism that Rodchenko rejected. The Black on Black paintings, similarly reductive, though not as extreme as the Black Square, emphasized instead the material qualities of picture-making.

In the early years of the Soviet Republic, Rodchenko, alongside his friend and colleague Wassily Kandinsky, was actively engaged in the government reform of art collections and education. In 1917, he became secretary of the Professional Union of Artist-Painters, joining the Izo (Otdel Izobrazitel'nykh Iskusstv or the Section of Visual Arts), as one of the presiding officials the following year.

In 1920, he was appointed the Director of the Museum Bureau and Purchasing Fund, a newly created agency in charge of the immense art collections transferred by the Bolsheviks from the palaces of the rich into the public domain. During his tenure, Rodchenko acquired 1,926 works of modern and contemporary art by 415 artists and established 30 public museums in Russian provinces.

Mature Period

While organizing the provincial museums, Rodchenko trained artists to serve the Communist state at the Higher Technical Artistic Studios. He taught the same principles that shaped his own artistic discourse; he rejected illusory representation as an outdated form hindered by the capitalist visual agenda, denounced painting as a domineering visual genre, preferring design, which challenged the notion of a work of art as a unique commodity, and, even more radically, promoted the idea of an artist as an engineer, a key creative force at the service of the masses.

In 1921, Rodchenko joined the Productivist movement, a group of artists devoted to the idea of incorporating artistic forms into the daily lives of common people. As a member of the group, Rodchenko designed notable utilitarian objects, including furniture, various household items, and textile patterns. More importantly, he became involved in bringing Constructivist forms into the mass visual propaganda of the Bolsheviks. His posters, such as Books (1924), became an icon of the early Soviet state and its artistic fervor. These works are still considered a pinnacle of modern graphic design today.

The ideas of Wassily Kandinsky may have been an important influence on Rodchenko in the early Soviet years, since the two were closely associated. But while Kandinsky was interested in the expressive possibilities of art, Rodchenko was increasingly interested in its potential as a laboratory for design and construction. This difference is reflected in his interest in line as an elemental component of painting. However, his final statements in painting returned to the issue of color; in 1921, he exhibited the groundbreaking triptych Pure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, Pure Blue Color (1921) comprised of purely monochrome panels of those colors.

In 1921, Rodchenko took a decisive, although temporary, break from painting. Instead, he concentrated on creating three-dimensional models of design objects, architectural sketches, and photography. He also created sets for film and theatre and designed furniture and clothes. From 1923 to 1925, he collaborated with the great avant-garde poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, illustrating some of his books and magazines for progressive Soviet writers such as LEF and NOVYI LEF.

It was through photography that Rodchenko enjoyed the most success in the 1920s. Employed as a correspondent for a number of Soviet newspapers and magazines, his photographs were exhibited all over the world. He was universally praised for his avant-garde compositions and experimental approach to focus and contrast in his photographs.

Late Years and Death

By the middle of the 1930s, Rodchenko fell out of favor with the Communist Party. The regime's visual ideology was completely transformed when Joseph Stalin came to power. The free-spirited avant-garde aesthetic was now actively suppressed by the state. Rodchenko and his wife were lucky not to perish in Stalin's Great Purges that swept through the Soviet Union and exterminated many individuals who came to prominence at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution. With Socialist Realism becoming the official art of the USSR., Rodchenko's paintings and designs were openly condemned by the authorities for so-called "formalism."

As such, Rodchenko turned to photojournalism. His photographic images epitomized the era of High Stalinism by depicting lavish parades, immense industrial undertakings, and the decisive transformation of agriculture. Naturally, Rodchenko was explicitly forbidden to capture the horrendous human toll of this sweeping modernization. In the 1940s, he returned to painting, executing a number of powerful abstract expressionist compositions. These works, however, were never to be seen by his contemporaries, for they openly contradicted the officially sanctioned aesthetics. He continued his work as a photographer throughout the Stalin years, until his death in 1956.

The Legacy of Alexander Rodchenko

As a key figure of the Russian modernist movement, the art of Alexander Rodchenko helped redefine three key visual genres of modernism: painting, photography, and graphic design. In his paintings, the artist further explored and expanded the essential vocabulary of an abstract composition. His series of purely abstract proto-monochrome paintings were influential to artists such as Ad Reinhardt and the Minimalists of the 1960s. In the field of photography, he established unprecedented compositional paradigms, which in many ways still define the entire notion of modern photographic art. Rodchenko's involvement with the Bolshevik cause further propelled the appreciation of his art in the leftist circles of the American avant-garde.

Influences and Connections

-

![Lyubov Popova]() Lyubov Popova

Lyubov Popova ![Vladimir Mayakovsky]() Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Mayakovsky![David Burliuk]() David Burliuk

David Burliuk![Vasily Kamensky]() Vasily Kamensky

Vasily Kamensky

-

![Cubism]() Cubism

Cubism -

![Futurism]() Futurism

Futurism -

![Russian Futurism]() Russian Futurism

Russian Futurism -

![Suprematism]() Suprematism

Suprematism ![Productivism]() Productivism

Productivism

-

![El Lissitzky]() El Lissitzky

El Lissitzky -

![Natalia Goncharova]() Natalia Goncharova

Natalia Goncharova ![Varvara Stepanova]() Varvara Stepanova

Varvara Stepanova

-

![Constructivism]() Constructivism

Constructivism -

![Abstract Expressionism]() Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism -

![Minimalism]() Minimalism

Minimalism -

![Conceptual Art]() Conceptual Art

Conceptual Art ![Monochrome Painting]() Monochrome Painting

Monochrome Painting

Useful Resources on Alexander Rodchenko

- Rodchenko and Popova: Defining ConstructivismOur PickBy Margarita Tupitsyn, Christina Kiaer

- Rodchenko: Photography 1924-1954By Alexander Lavrentiev

- Rodchenko: DesignBy John Milner

- The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917-1946By Victor Margolin