Summary of Georges Seurat

Georges Seurat is chiefly remembered as the pioneer of the Neo-Impressionist technique commonly known as Pointillism, or Divisionism, an approach associated with a softly flickering surface of small dots or strokes of color. His innovations derived from new quasi-scientific theories about color and expression, yet the graceful beauty of his work is explained by the influence of very different sources. Initially, he believed that great modern art would show contemporary life in ways similar to classical art, except that it would use technologically informed techniques. Later he grew more interested in Gothic art and popular posters, and the influence of these on his work make it some of the first modern art to make use of such unconventional sources for expression. His success quickly propelled him to the forefront of the Parisian avant-garde. His triumph was short-lived, as after barely a decade of mature work he died at the age of only 31. But his innovations would be highly influential, shaping the work of artists as diverse as Vincent Van Gogh and the Italian Futurists, while pictures like Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte (1884) have since become widely popular icons.

Accomplishments

- Seurat was inspired by a desire to abandon Impressionism's preoccupation with the fleeting moment, and instead to render what he regarded as the essential and unchanging in life. Nevertheless, he borrowed many of his approaches from Impressionism, from his love of modern subject matter and scenes of urban leisure, to his desire to avoid depicting only the 'local', or apparent, color of depicted objects, and instead to try to capture all the colors that interacted to produce their appearance.

- Seurat was fascinated by a range of scientific ideas about color, form and expression. He believed that lines tending in certain directions, and colors of a particular warmth or coolness, could have particular expressive effects. He also pursued the discovery that contrasting or complementary colors can optically mix to yield far more vivid tones that can be achieved by mixing paint alone. He called the technique he developed 'chromo-luminism', though it is better known as Divisionism (after the method of separating local color into separate dots), or Pointillism (after the tiny strokes of paint that were crucial to achieve the flickering effects of his surfaces).

- Although radical in his techniques, Seurat's initial instincts were conservative and classical when it came to style. He saw himself in the tradition of great Salon painters, and thought of the figures in his major pictures almost as if they were figures in monumental classical reliefs, though the subject matter - the different urban leisure pursuits of the bourgeois and the working class - was fully modern, and typically Impressionist.

- In Seurat's later work he left behind the calm, stately classicism of early pictures like Bathers at Asnières, and pioneered a more dynamic and stylized approach that was influenced by sources such as caricatures and popular posters. These brought a powerful new expressiveness to his work, and, much later, led him to be acclaimed by the Surrealists as an eccentric and a maverick.

The Life of Georges Seurat

“Some say they see poetry in my paintings; I see only science” was what Seurat said and his development as an artist was a similar progression away from the scenic and emotional, and into the calculated and analyzed.

Important Art by Georges Seurat

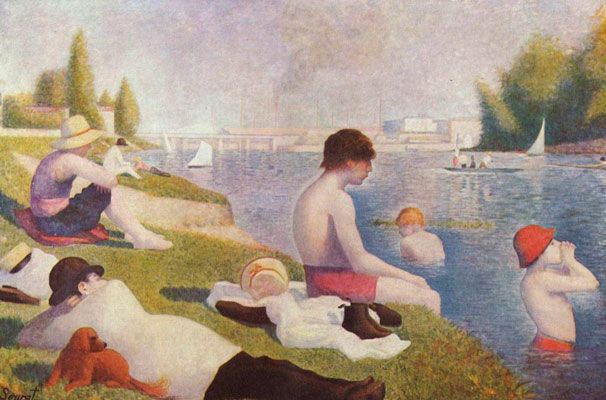

Bathers at Asnières

Seurat's first important canvas, the Bathers is his initial attempt at reconciling classicism with modern, quasi-scientific approaches to color and form. It depicts an area on the Seine near Paris, close to the factories of Clichy that one can see in the distance. Seurat's palette is somewhat Impressionist in its brightness, yet his meticulous approach is far removed from that style's love of expressing the momentary. The scene's intermingling of shades also demonstrates Seurat's interest in Eugene Delacroix's handling of shades of a single hue. And the working-class figures that populate this scene mark a sharp contrast with the leisured bourgeois types depicted by artists such as Monet and Renoir in the 1870s.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte

Seurat's Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte was one of the stand-out works in the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition, in 1884, and after it was shown later that year, at the Sociéte des Artistes Indépendents, it encouraged critic Félix Fénéon to invent the name 'Neo-Impressionism.' The picture took Seurat two years to complete and he spent much of this time sketching in the park in preparation. It was to become the most famous picture of the 1880s. Once again, as in Bathers, the scale of the picture is equal to the dimensions and ambition of major Salon pictures. The site - again situated on the Seine in northwest Paris - is also close by. And Seurat's technique was similar, employing tiny juxtaposed dots of multi-colored paint that allow the viewer's eye to blend colors optically, rather than having the colors blended on the canvas or pre-blended as a material pigment. The artist said that his ambition was to "make modern people in their essential traits move about as they do on [ancient Greek] friezes and place them on canvases organized by harmonies." But the classicism of the Bathers is gone from La Grand Jatte; instead the scene has a busy energy, and, as critics have often noted, some of the figures are depicted at discordant scales. It marked the beginning of a new primitivism in Seurat's work that was inspired in part by popular art.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

La Seine à la Grande-Jatte

La Seine à la Grande-Jatte of 1888 shows the artist returning to the site of his most famous painting - A Sunday on La Grande Jatte painted two years prior. This later composition demonstrates Seurat's continued interest in form and perspective, but reveals a much softer and more relaxed technique than La Grande Jatte. The soft atmosphere is made up of a myriad of colored dots that mix optically to mimic the effects of a luminous summer day.

Oil on canvas - Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

Young Woman Powdering Herself

Young Woman Powdering Herself is a portrait of Seurat's mistress Madeleine Knobloch. It is an adoring likeness that jokingly contrasts the classical monumentality of the figure against the flimsy Rococo frivolity of the setting. It is also strongly marked by Seurat's increasing interest in caricature and popular art, sources which lent a new expressiveness to his work which accorded with the growing contemporary interest in Symbolism. Knobloch was a working-class woman with whom Seurat maintained a long-term secret relationship, keeping her separate not only from his bourgeois family but also from his bohemian friends. When the painting was shown in 1890, her identity remained concealed. Knobloch was given some of Seurat's paintings as an inheritance but she cut off all communication with his family after his death.

Oil on canvas - The Courtauld Gallery, London

Circus Sideshow

Circus Sideshow is considered one of Seurat's major figure paintings. Yet it is much more condensed than his other mural-size paintings. This was Seurat's first nocturnal painting and it debuted at the 1888 Salon des Indépendants in Paris. It depicts a ringmaster and musicians under twinkling gaslight who are attracting a crowd of potential ticket buyers. The composition was drawn from on-site sketches he made in the spring of 1887, when Frenand Corvi's traveling circus performed in Paris (it appeared regularly in Paris between the 1870s and the First World War). Though Seurat frequently attended circus-like events in his leisure time, this painting was the first important picture Seurat dedicated to a scene of popular entertainment. The pattern of circles, ovals, and rectangles in the background has attracted much notice from critics, as many of the forms are hard to explain in terms of the structure of the setting. It has been argued that they derive from Seurat's understanding of various contemporary theories of expression, which advocated the use of particular forms and colors to convey particular types of emotion.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Circus

Seurat's early paintings often feature a remarkable stillness, even with complex figure compositions, but The Circus features a scene of dynamic movement, and is typical of his late style. The scene is borrowed from an anonymous poster for the Nouveau Cirque, printed in 1888, although the horse and bareback rider have been reversed. The figure in the first row of seats, with a silk hat and a lock of hair visible under it, is the painter Charles Angrand, a friend of Seurat's. This painting was Seurat's last, and was left unfinished when he died suddenly in March of 1891. It was sold shortly thereafter to his friend Paul Signac.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Biography of Georges Seurat

Childhood

Georges Seurat was born in Paris December 2, 1859, the youngest of three children. His father, Chrysostome-Antoine Seurat, was a bailiff; his mother, Ernestine Faivre, came from a prosperous family that had produced several sculptors. Seurat's eccentric father had already retired with a small fortune by the time Seurat was born, and he spent most of his time in Le Raincy, some 12 kilometers from the comfortable family home in Paris. The young Seurat lived with his mother, his brother Émile, and his sister Marie-Berthe.

In 1870 the family temporarily relocated to Fontainebleau, where they stayed during the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent Paris Commune rebellion. Seurat began to take a serious interest in art as a boy and was encouraged by informal lessons from his maternal uncle, Paul Haumonté, a textile dealer and amateur painter.

Early Training

Seurat's formal training began around 1875, when he entered the local municipal art school under the sculptor Justin Lequien. There, he made a friend of Edmond Aman-Jean (1858-1935) and together they entered the École des Beaux-Arts run by Henri Lehmann, a disciple of the Neo-Classical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Seurat attended the Academy from February 1878 until November 1879. The curriculum placed particular emphasis on drawing and composition, and most of Seurat's time was spent sketching from plaster casts and live models.

Seurat spent his free time conducting his own artistic studies and frequently visited museums and libraries throughout Paris. He also sought instruction from the painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose specialty was large-scale classical, allegorical scenes. Seurat's sketches dating to 1874 include copies of Holbein's drawings, a sketch of Nicolas Poussin's hand from the acclaimed self-portrait in the Louvre, and figures from drawings by Raphael.

Charles Blanc's The Grammar of Painting and Engraving (1867) and Michel-Eugène Chevreul's The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors (1839) introduced Seurat to color theories and the science of optics that became central to his thinking and practice as a painter. Chevreul's discovery that by juxtaposing complementary colors one could produce the impression of another color became one of the bases for Seurat's Divisionist technique.

In April 1879, Seurat visited the Fourth Impressionist exhibition. This was the first time he had seen their paintings and the work of Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, artists liberated from the rigidities of academic rules, greatly influenced his later experimentation. But in November his military service started in Brest, where he devoted all his spare time to reading and filling sketchbooks with studies of fellow recruits, seascapes, and street scenes.

In the following years, Seurat extended his understanding of color theory and the effects of color on the human eye. He also studied the brushwork of Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix and read Ogden N. Rood's Modern Chromatics (1879), which proposed that artists should experiment with color contrast by juxtaposing small colored dots to see how they are blended by the eye.

Mature Period

Seurat began to apply his theoretical research to compositions executed between 1881 and 1884, culminating in his first major painting project, the Bathers at Asnières (1884). This monumental canvas depicted a group of workers relaxing by the Seine and was based on numerous small oil sketches and figure studies. The final composition is an accomplished rendition of the light and atmosphere of high summer. It is largely rendered in a criss-cross brushstroke technique known as balayé and was later re-touched by Seurat with dots of contrasting color in certain areas.

Seurat submitted Bathers to the state-sponsored Salon in 1883, but the jury rejected it. Subsequently, Seurat and several other artists founded the Société des Artistes Indépendants, enabling him to exhibit Bathers in June of 1884. There he met and befriended fellow artist Paul Signac who was greatly influenced by Seurat's techniques.

After the Bathers Seurat began work on Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte, a mural-sized painting that took him two years to complete. Many times the artist visited La Grande Jatte, an island in the Seine located in the Parisian suburb of Neuilly, making drawings and more than thirty oil sketches to prepare for the final work. In the winter of 1885-86 he reworked the painting in the technique that he called "chromo-luminarism", also known as Divisionism or Pointillism. This technique uses dots of contrasting color that, when viewed at a distance, interact to create a luminous, shimmering effect. He also repainted sections of the Bathers in the same style around 1887.

Seurat exhibited La Grande Jatte at the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition in May 1886. Its visual effects of light and color, as well as its complex representation of different social classes established Seurat as the leader of a new avant-garde.

Late Period

The exhibition of La Grande Jatte in 1886 unexpectedly aroused interest in Seurat's work internationally. Soon after the exhibition, Seurat was mentioned in an avant-garde review and some of his paintings were shown by the renowned art dealer Paul Durant-Ruel in both Paris and New York City.

During this time he began associating with a very enclosed group of Symbolist artists and writers based in Paris. His new associations troubled his friends Pissarro and Signac, who believed he was forsaking the pure study of color and light in favor of idealized subjects. Seurat's last major works depict Paris nightlife and all share a similar muted palette that differs greatly from the vibrancy of his earlier paintings.

Apart from a brief period of renewed military service in summer 1887, Seurat spent his summers on the Normandy coast, painting seaside scenes of Honfleur in 1886, Port-en-Bessin in 1888, Le Crotoy in 1889 and Gravelines in 1890. In winter he finished these paintings and produced large figure compositions. Although executed in his Pointillist style, the dots tended to be finer and more spaced out, giving the paintings a more spontaneous appearance.

In 1889, Seurat traveled to Belgium, where he exhibited at the Salon des Vingt (XX) in Brussels. After returning from this trip, he met Madeleine Knobloch, a 20-year-old model, and started secretly living with her. Knobloch gave birth to a son in February 1890, unbeknownst to his friends and family.

At his exhibition in the Salon des Indépendants the same year, Seurat showed his only known portrait of Madeleine Knobloch: Young Woman Powdering Herself.

Madeleine Knobloch was pregnant again at the beginning of 1891, while Seurat was at work painting The Circus. This painting would remain unfinished. On March 26, Seurat fell suddenly ill with a fever and died three days later. His son died of a similar illness in 2 weeks, and was buried alongside Seurat at the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

The Legacy of Georges Seurat

Seurat was only 31 when he died, yet he left behind an influential body of work, comprising seven monumental paintings, hundreds of drawings and sketches, and around 40 smaller-scale paintings and sketches. Although his oeuvre is relatively small in quantity, it had a lasting impact. He was among the first artists to make a systematic and devoted use of color theory, and his technical innovations influenced many of his peers. When the term Neo-Impressionism was coined by art critic Félix Fénéon in 1886, it was to describe Seurat, Signac, and Pissarro's new style of painting and their rejection of the spontaneity of Impressionism.

Poised between Impressionism in the 19th century, and Fauvism and Cubism in the early-20th, Neo-Impressionism brought with it a new awareness of the surface qualities of painting, and of decorative effects, thereby contributing to the development of abstraction.

Seurat is often cited by artists with an interest in the visual effects of color, form, and light. Painter Bridget Riley has credited him with influencing her particular brand of Op art.

Influences and Connections

-

![Camille Pissarro]() Camille Pissarro

Camille Pissarro -

![Claude Monet]() Claude Monet

Claude Monet -

![Édouard Manet]() Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet ![Felix Feneon]() Felix Feneon

Felix Feneon

Useful Resources on Georges Seurat

- Seurat: A BiographyBy John Rewald

- Georges Seurat, 1859-1891: The Master of Pointillism (Basic Art)By Hajo Duchting

- Seurat (World of Art)Our PickBy John Russell

- Georges Seurat (Rizzoli Art Series)By Norma Broude

- Seurat and the Making of 'La Grande Jatte'Our PickBy Robert L. Herbert, Neil Harris

- Georges Seurat 1859-1891By Robert L. Herbert

- Georges Seurat: The DrawingsOur PickBy Jodi Hauptman, Karl Buchberg, Hubert Damisch, Bridget Riley, Richard Shiff, and Richard Thomson

- Georges Seurat: The Art of VisionBy Michelle Foa

- Masters of Art: SeuratOur PickBy Pierre Courthion

- Seurat's Circus SideshowBy Richard Thomson

- Ways of Pointillism: Seurat, Signac, Van GoghBy Klaus Albrecht Schröder

- The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to SeuratBy Martin Kemp