Summary of Body Art

If life is the greatest form of art, then it seems only natural for artists to use the physical body as a medium. This is exactly what many Performance artists did to express their distinctive views and make their voices heard in the newly liberated social, political, and sexual climate that emerged in the 1960s. It was a freeing time where artists felt empowered to make art ever more personal by dropping traditional mores of art making and opted to using themselves as living sculpture or canvas. This resulted in direct confrontation between artist and audience, producing a startlingly intimate new way to experience art.

The body artists were a loose group - mostly categorized as a group by critics and art historians - which developed early within the Performance Art movement. The larger movement's main impetus was to evolve definitions of art to include situations in which time, space, the artist's presence, and the relationship between artist and viewer constituted an artwork. To the body artists, the artist's presence translated to an artist's physicality; not only did they need to personally fulfill a role in the presentation of an artwork, their own flesh and blood would become a key figure in the work as well.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Body art diffused the veil between artist and artwork by placing the body front and center as actor, medium, performance, and canvas. Lines were erased between message and messenger or creator and creation, giving new meaning to, and amplifying the idea of, authentic first person perspective.

- In the post-1960s atmosphere of changing social mores and thawed attitudes toward nudity, the body became a perfect tool to make the political personal. What else could be more demonstrative of an artist's passions, opinions, and voice than a direct, literal representation of the self as the prime channel of communication in making a point? Especially in matters of the hot button issues of the time, using the body became a way for an artist to connect the individual with the universal human experience - one person asking others to resonate as a whole.

- By forcing audiences to partake in oftentimes violent, jarring, shocking, or unimaginable experience, Body art asked its viewers to consider the role they were playing in the dark and uncomfortable spaces between innocent bystander and culpable voyeur.

- Whether regarded as a temple and honored as a sacred vessel or treated as an object to test, wield, or destruct, the body was placed on a pedestal and became a literal (rather than just appropriated, imagined, or created by the artist's hand) collaborator in the art making process. This focus so narrowly directed toward the body, ultimately forced viewers to hone a spotlight on their own physicality and its role in their fleeting existence.

- Body art can be seen as a forebear to today's general mainstream acceptance of tattooing, piercing, scarring, or otherwise adorning the body as a means to establish one's own individuality as well as connections to certain forms of community and likeminded mentality.

Overview of Body Art

"The body is the medium," Marina Abramović has famously said, and in pieces like Rhythm O (1974) she used her own body as the subject to pioneer Body art.

Artworks and Artists of Body Art

Anthropométrie sans titre

In his Anthropometries series, Yves Klein covered nude women in blue paint and had them press, drag, and lay themselves across canvases to create bodily impressions. The piece was inspired in part by photographs of body-shaped burn-marks on the earth, which were caused by the atomic explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Klein crafted this idea into a performance piece, hosting a formal event where guests observed the nude models executing the piece.

The work makes reference to the painting practices of Jackson Pollock, who would pour and drip paint onto his canvases. Klein takes the physical element of painting even further by adding an audience and using the human body to spread the paint. In utilizing the female body as canvas and paintbrush, Klein challenged viewers' expectations about the artistic process and precipitated a new direction for performance art. By incorporating the human body into the act of creating art, Klein gave the performativity of the body an unprecedented privilege within its discourse.

Notably, Klein's work and his objectifying use of women's bodies is at odds with much of the feminist body art which came after it. Many later female artists would have objected to this use of women's bodies as mere tools, rather than as active participants. Yet many of the women who participated in Anthropometries at the time, said they felt as if they were co-creators of the work and described the process as being fun.

Performance; oil on canvas on paper, resin - Musée Cantini, Marseille, France

Sex Obsession Food Obsession Macaroni Infinity Nets & Kusama

In this photograph, Yayoi Kusama lies naked on a couch covered with her soft sculpture accumulations comprised of phallic shaped sprouts. According to the artist, "The reason my first soft sculptures were shaped like penises is that I had a fear of sex as something dirty. People often assume that I must be mad about sex, because I make so many such objects, but that's a complete misunderstanding. It's quite the opposite - I make the objects because they horrify me. Reproducing the objects, again and again, was my way of conquering the fear." In the background is spread a sea of macaroni pasta. She is slim and stylish, with a fashionable haircut and painted with polka dots that allow her to blend into the psychedelic scene as an intrinsic and inseparable part of the artwork. For Kusama, there is no difference between life and art and she boldly states this within a tableaux that all the while winks an eye at traditional pin-up layouts of women.

Amelia Jones argues that Kusama is "racially and sexually at odds with the normative conception of the artist as Euro-American male. Rather than veil her differences (which are seemingly irrefutably confirmed by the visual evidence of her 'exotic' body), Kusama exacerbates them through self-display in a series of such flamboyant images." In doing so, she also subtly criticizes the canon's normativity and conformity.

Macaroni, paint, photograph

Body, Sign, Action

In 1970 feminist artist VALIE EXPORT staged a performance where she was tattooed with an image of a garter strap and stocking top on her thigh. The garter refers to the fetishizing of women's underwear and, by extension, of women's bodies. By permanently tattooing herself with a symbol of sexualization and objectification, EXPORT posits that by extension, as a woman, her whole body is a permanent subject for male visual pleasure.

However, by turning this into a public act and then photographing herself with the tattoo in the nude, EXPORT co-opts a symbol of female restriction and transforms it into one of personal empowerment - a badge of liberation. In her own words, "incorporated in a tattoo, the garter belt signifies a former enslavement, is a garment symbolizing repressed sexuality, an attribute of our non-self-determined womanhood. A social ritual that covers up a bodily need is unmasked, our culture's opposition to the body is laid open."

Cultural historian Sabine Kampmann argues that EXPORT made a radical choice in making her own skin the substrate for her art: "EXPORT makes an association between human skin, vellum (hide prepared for scripture), and books to legitimize her extraordinary choice of skin as material for her artwork." She was making the statement that writing on her own skin was no different than writing on a piece of paper, albeit with messages whose permanence perhaps carried greater weight.

Kampmann also suggests that EXPORT's work may be the first time that a tattoo had been used as a work of fine art in art history. This links to the use of the term "body art" today to refer to tattoos and body ornamentation more generally.

Tattoo

Einhorn (Unicorn)

Early in Rebecca Horn's career she contracted lung poisoning from repeatedly inhaling toxic materials in the making of her art. She was sent to a sanitarium for two years to recover and during this time she became fascinated by the hospital setting and the limitations of the human body. She began experimenting with making "body extensions" as a coping strategy in which she would use medical materials such as bandages, trusses, and prostheses to create wearable sculpture. Horn said about her debilitating experience, "you crave to grow out of your own body and merge with the other person's body, to seek refuge in it." These pieces were manifestations of the desire, which allowed Horn to explore her personal space and how the body could interact with its physical environment.

Horn was also interested in mythology, which shows up in Einhorn. The piece may be read several ways. Historian Skye Alexander argues that the "strap on" horn "recalls the unicorn's link to chastity" and the many complex sexualized associations evoked by a woman's naked body in classical art. But the single horn can also be seen a phallic symbol co-opted boldly here by a woman to offer a new model for empowering the female body, which embraces its own sexuality and lays claim to its own sexual power. In either case, Einhorn explores how the body (and particularly the female body) can be both enhanced and restricted by art.

Material body extension; performance; photographic documentation - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Shoot

Shoot is the seminal piece for which Chris Burden sealed his membership in infamy. In 1971, the highly provocative artist asked a friend to shoot him with a .22 rifle from a distance of 15 feet in a public gallery setting. The bullet was originally supposed to nick the side of Burden's arm, but the shooter was slightly off target and the bullet went through the arm instead. This piece presented a literal demonstration of what happens when a person is shot so that the audience could experience it live. The viewer was forced to experience visceral emotions such as shock while mentally reconciling the moment in front of them. In describing the piece, Burden stated that "it was really disgusting, and there was a smoking hole in my arm."

Burden's work remarked upon society's desensitization to violence, and the dissociation between seeing something horrible happen live versus on television. Amelia Jones also suggests that Burden's work presented him as a sort of martyr for art. She goes on to argue that Burden's "deadpan submission of himself to the violence of others (who are ordered and/or scrupulously controlled by Burden), reiterated normative codes of masculine artistic genius-as-transcendent; and yet the reiteration is so insistent and so exaggerated, Burden might also be interpreted as unhinging these codes through parody."

.22 rifle and bullet - N/A

The Conditioning

Gina Pane was a French artist who was a key member of Art Corporel - the French body art movement she helped found in the early 1970s. One of her most famous works is The Conditioning, where she lay on a metal bed frame above lit candles for half an hour. This was an extremely painful experience for the artist, and the audience could see her physical suffering in the automatic pain responses of her body, such as flinching and wringing her hands. Critic Sam Johnson argues that, "while the candles and bed suggested ideas of sexual love and pleasure, the manner in which Pane positioned her body around these objects caused her harm and surreptitiously threw up questions around the fixed notions of pleasure and pain." Pane's work draws the viewer's attention to the way in which female sexual experience (especially in the female loss of virginity) is regularly associated with pain and suffering in common formulations.

This piece is a good example of how an artist's self-inflicted pain caused the audience to feel empathy and also a deep sense of discomfort through watching the bodily suffering of another human being. As per usual in the art viewing setting, unless otherwise told, the typical rules are not to touch the art. This caused tension for viewers as they were unsure whether they were permitted to step in, interrupt the scene, or make attempts to stop it. Pane's works were often of this nature, showing violence to the body in gestures that ranged from razor blade cutting to putting fires out with her bare hands, in order to lay bare human fragility.

Candles, metal bed

Imagen de Yagul

Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta was best known for over 200 pieces of "earth-body" artworks in which she utilized a collaboration between her body and the earth as a sculptural medium. She was on the forefront of the feminist art movement and explored themes of violence, loss, existence, and belonging. Imagen de Yagul was the first in Mendieta's renowned series of silhouette portraits in which she would trace the outline of her body in various locations between Mexico and Iowa and then photograph the imprints left in her absence. It consists of her nude body lying within an open Zapotec tomb in the ancient city of Yagul as flowers, leaves and other elements of nature envelop and obscure her - homage to the inevitable and organic cycles of life and death. It is the only of the series in which her body remains in the resulting photograph - the rest resembles burnt or scarred portraits in the land. Because Mendieta died a tragic death, falling from the window of an apartment building she shared with her artist husband Carl Andre, these works lend an eerie foretelling of her fate.

Lifetime color photograph

Rhythm 0

In Rhythm 0, multiple aspects of Body art were combined to forge one of the most memorable performance pieces in history. Audience participation was central to the piece and sparked an interesting sociological glimpse into mob mentality. It covered the gamut from positive to negative human behaviour, touched upon ideas of pain, pleasure, shock and submission and positioned the body as equal parts canvas, medium, and object of manipulation - in both sexual and suffering lights.

With a description reading "I am the object," and, "During this period I take full responsibility," Abramović invited spectators to use any of 72 items provided in the gallery on her body in any way they desired, completely giving up control. She made her own body the subject of her artwork, but did not control the way in which the narrative unfolded. Instead, she passively offered up her body to her audience, exploring how they would respond to this act, which carried undertones of the archetypal self-sacrificing woman.

Rhythm 0 was exemplary of Abramović's belief that confronting physical pain and exhaustion was important in making a person completely present and aware of his or her self. This work also reflected her interest in performance art as a way to transform both the performer and the audience. She wanted spectators to become collaborators, rather than passive observers. The audience engaged in various ways: they wrote words on her skin; they took photographs; one man cut off her shirt and another nicked her neck with a knife and sucked out the blood. By the end of the performance, the audience had revealed itself as two types: those who sought to harm Abramović (holding the loaded gun to her head) and those who tried to protect her (wiping away her tears). Ultimately, after she stood motionless for six hours, the protective audience members insisted the performance be stopped, seeing that others were becoming increasingly violent.

72 materials of pleasure and pain including a gun, a bullet, a comb, a saw, olive oil, cake, wire and sulphur

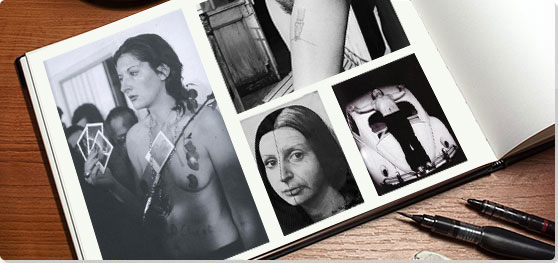

S.O.S. Starification Object Series

This is one of Wilke's best-known works; it constitutes a series of photographs of the artist posing topless much like a glamorous pin-up girl (that Wilke herself had all the attributes to be) in which she parodies traditional representations of "femininity". The difference between these photographs and typical glamour shots is that Wilke has created tiny sculptures out of chewing gum and stuck them to her body. The gum is formed into vulvar shapes, a shape that she explored in other media throughout the 1960s. The title, "Starification" is a neologism that refers to a concept of creating a "star" or celebrity. The term also recalls "scarification," which could refer to the coming-of-age scarring rituals undertaken in some non-Western cultures or the numbered tattoos on Holocaust victims, while also suggesting a relation between women's bodies and wounds/vulnerability. By juxtaposing ideas of celebrity and scarring, Wilke points to the complexity of responses to images of women's bodies.

In this photography series, she presents her own body as both an object for viewing and as the agent of the objectification. Her goal, therefore, is to bring attention to depictions of women in popular culture, thus dismantling stereotypes about femininity and disrupting the pleasures of the male gaze. Art historian Joanna Frueh, for example, sees the Starification Object Series as evidence of Wilke "representing herself as a woman damaged by female embodiment in a culture that subordinates woman to man."

Photographs and chewing gum - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Interior Scroll

Carolee Schneemann undertook this famous performance (in front of an audience of mostly female artists) at an exhibition of paintings and performances entitled Women Here and Now. Schneemann undressed until she was wearing only an apron, proceeded to apply paint to her body, and read from her own book Cézanne, She was a Great Painter (1975). She then took off the apron and pulled a scroll of paper from her vagina while reading the contents aloud. The text was drawn from a film made by Schneemann in which she recorded a male filmmaker articulating the traditional pigeonholing of intuition, emotion and certain bodily functions as "female" and logic and rationality as "male."

Schneemann used this visceral bodily performance in order to exteriorize the mystique often appointed to the interior of a woman's body. She wished to close the wide gap of disconnect between a woman's experience of her own body and the representations of the female body throughout history. By placing her vagina front and center, and using it to birth a provocative message, she proved no longer interested in suppressing the authentic feminine, or asking permission to fully inhabit her female sexuality or reality. She was staking claim to these things on her own. She forced viewers to face their own denial of a fully embodied female reality.

As critic Amelia Jones puts it, "Schneemann extended her sexualized negotiation of the normative (masculine) subjectivity authorizing the modernist artist, performing herself in an erotically charged narrative of pleasure that challenges the fetishistic and scopophilic "male gaze"."

Performance

Beginnings of Body Art

Body art has its roots in the Performance Art movement, which sprung up among avant-garde artists in the late 1950s when artists such as John Cage and members of the Fluxus group were staging "happenings." These were performances that accentuated a content-based meaning with a dramatic flair instead of traditional performances meant for purely entertainment purposes. An interest in performance as an alternative means of artistic expression began to spread through the US, Europe, and Asia where collectives like the Viennese Actionists and Japan's Gutai Art Association sprang up to produce live-action artworks that erased the need for an end product or commodity. In many of these progressive new performances, the artist's body became subject of, or object within, the overall piece, creating a literal embodiment of the artwork.

The Nouveau Realisme movement in France was instrumental in developing performance art in a way, which focused on the body of the artist and other participants, arguably producing the first "body art". Yves Klein, in particular, explored the idea of the human body as tool, medium and subject, particularly in his Anthropometries series where he instructed naked women to drag and rub their painted bodies against very large canvases that were placed on the walls and floors.

Although body art was frequently performative, it did not always involve a live, performance-based process in front of an audience. Many body artists, such as Hannah Wilke and Ana Mendieta, used photography or video art in order to stage their bodies as central to the artwork.

Against Abstract Expressionism

In the early 1960s, Abstract Expressionism dominated the art scene in the US. The canvases by artists such as Jackson Pollock were created through a painting process that was highly action-oriented. However, the abstract qualities of the movement meant it wasn't suited for making political or other content-driven declarative statements. It was also a male-dominated art form, and many women artists were seeking a new form of art that would highlight the female condition in radical ways beyond the domestic. In 1963, Carolee Schneemann, who had previously worked as a painter, started carrying out performances using her own body to challenge the domination of Abstract Expressionism. In her performance Eye Body: 36 Transformational Actions, she rejected the coldness of Abstract Expressionism by painting and affixing multiple items to herself and then merging as an eroticized character into her other painted environments. The resulting photographs represented another dimension in which her gestural, creative emotion was still felt even as she was inserted into the work itself. In her own words, "in 1963 to use my body as an extension of my painting-constructions was to challenge and threaten the psychic territorial power lines by which women were admitted to the Art Stud Club."

The Cultural Revolution

Body art's birth during the cultural revolution of the 1960s was well timed due to the more relaxed attitudes affecting the Western world. The age of free love and psychedelic drugs created new freedoms for both men and women in how they looked and acted. Societal expectations were loose and people were able to express themselves more meaningfully through their clothes and appearance. The use of the body to make political and sexual statements was edgy but not all together too far out in a world besieged by a new sense of wild styles with an emphasis on personal freedom and empowerment.

It was also an era of political and social activism, where throngs of students were protesting the Vietnam War, nuclear armament, the lack of equal rights and many other trigger issues, oftentimes by using their bodies as barriers, shields or simply immovable presences. Famously, in 1969 John Lennon and Yoko Ono staged a weeklong "bed-in", where they lay in bed and made love, as a protest for peace. More widely, people staged marches and chained themselves to trees to support feminism, environmentalism and anti-war sentiments.

The Rise of Feminism

This involvement of the body was something that resonated particularly strongly with the Feminist movement, which had been burgeoning since the early 1960s. A large number of women artists chose performance as their medium of choice at this time, often using their own bodies as powerful vehicles of demonstration, rebellion and voice. Performance, photography, and video art became popular choices for female artists, to counteract the dated historical weight and onus of more traditional formats such as painting. As these current forms mirrored the electricity of the changing times this was an opportunity for a fresh feminist aesthetic in which the female body would take center stage, not as the by-product of the male gaze but as a self-claimed artistic subject-object.

However, the body art movement was not just restricted to women artists and artists working with a feminist aim. Other artists using their own bodies in their work included Dennis Oppenheim, who once experimented with the material of the body by embedding his discarded fingernail into a wooden floorboard in exchange for a sliver of wood into his own finger. Chris Burden's controversial piece Shoot(1971) featured the artist being shot in the arm by an assistant. Vito Acconci also provoked with his taboo piece of the same year, Seedbed, where he hid beneath the gallery floor and whispered fantasies about the visitors while masturbating, fantasies that were simultaneously piped out through the loud system for all guests to hear.

Body Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Pain and Suffering

In many body art performance pieces, the artists inflicted physical pain on themselves in front of their audience. By causing pain and cutting, burning, scarring or otherwise marking the skin, artists could bring their performances into a realm that was unequivocally visceral and bodily, making physical sensation a part of their artwork in a way that had never been done before. Examples include Chris Burden, who had nails driven through his hands to attach him to a Volkswagen car in Trans-fixed (1971). Burden's use of his own body made his experience more relatable to his audience, because they could imagine the pain being inflicted as if it were their own. In Thomas Lips (1975), Marina Abramović cut a five-pointed star into her belly and then laid until nearly unconscious on a cross made of ice.

Female Sexuality

For many feminist body artists, using their own body as the subject and object in their artwork drew out a clear connection with sexuality. They used body art to draw attention to the way in which our understanding of the gendered body and our understanding of sexuality and eroticism are intrinsically linked. Carolee Schneemann criticized traditional depictions of women's bodies, which refuse to acknowledge that women are sexual and physical beings in the same way as men. Her works such as Interior Scroll (1975) made manifest the interiority of the female body, something that is usually hidden. For other feminist artists such as Hannah Wilke, presenting her own nude body as an object for visual interest allowed her to claim her body and her sexuality as her own.

These artists were not only furthering a feminist agenda, they also pushed the limitations of the art world in general. The vagina informed a metaphoric birth of new artistic dialogues, expanded opportunities to unravel the feminine mystique and multiple voices in the fray as a loud and reverberating denouncement of the traditional male gaze. Some of these women were creating works that simply could not be produced by a man; they were leveling the playing field and breaking old barriers with gender as their weapon.

The Body as Canvas

Some body artists used the human body as a site for making marks or applying paint, turning the skin into a surrogate for canvas. For example, Polish artist Ewa Partum's 1975 work Change was a performance in which she stood naked while several make-up artists painted half of her body to look several decades older, replicating wrinkles and stretch marks. For Partum, using her body as both a medium and subject for her art allowed her to draw attention to a key aspect of female bodily experience and the double standards surrounding the sexualization of women's bodies at different stages of their lives. This use of the body marks a turning away from the traditional materials for art making and represents a move towards a form of art where the artist and the artwork are more closely integrated. It is notable that in common parlance, "body art" refers to tattoos and body ornamentation. Significantly, artists during this era such as VALIE EXPORT began to use permanent mediums such as tattooing in their work.

Body: A New Medium

In considering the body as a new medium, artists also looked toward the use of bodily liquids and other bodily parts. For example, Austrian Vienesse Actionist Hermann Nitsch staged elaborate ritual productions under the title Das Orgien Mysterien Theater in which urine, feces, and blood were commonly slathered over bodies of the performers. French artist Michel Journiac's most famous action was Mass for a Body (1969) where he offered pieces of blood sausages made with his own blood to the audience and invited them to eat - a parody of Catholic liturgy. His fellow art corporel member Gina Pane practiced cutting herself regularly to engage with blood much like paint in her pieces. In Andy Warhol's Oxidations series, (1977), he invited friends to urinate on canvas painted with metallic pigment in order to create abstract patterns birthed by the chemical reaction.

Audience Participation: Shock, Discomfort, and Reflection

Many body art works were highly confrontational pieces performed in front of an audience. These performances asked audience members not only to question their role as spectators but also to willingly get uncomfortable. They also, secondarily, evoked thoughts within viewers around voyeurism versus action and personal accountability versus following the rules. When artworks included highly sexual aspects or involved the infliction of pain, the audience was led to consider their own agency in the performance.

In several of Marina Abramović's performances, audience members made the decision to intervene when she seemed in danger either from her own performance or from other audience members. In 1968, VALIE EXPORT invited her audience (who were made up of random individuals she met on the street) to come uncomfortably close. Her Touch Cinema consisted of her wearing a Styrofoam box with a curtained opening. Passersby were invited to put their hands inside and feel her naked breasts, forcing them to question their interaction with the female body on screen versus in physical form. In some cases, viewers were led to consider their own relationship to the body as well as their body's relationship to various concepts such as intimacy. In Abramović and Ulay's famous Imponderabilia, (1977), visitors to a gallery were forced to walk between the two naked artists who stood facing each other in the entrance door in order to get inside. Patrons had to make choices: who would they face while entering, who would they be willing to touch as they passed, and how would this experience ultimately make them feel within their own skin?

Later Developments - After Body Art

Body art has only recently been recognized as an art form that is separate to Performance art. Art critic Amelia Jones in her 1998 book Body Art: Performing the Subject made this distinction most clearly and extensively. Jones notes that the 1980s saw a move away from body art, which coincided with a "disembodiment" inherent in the politics of the Reagan-Thatcher era. She claims that the 1990s, however, "witnessed a dramatic return to art practices and written discourses involving the body."

The Role of Technology

From the 1990s through present day, many body artists have looked toward rapidly advancing technologies and the Internet to articulate their work. Some original feminist artists, such as Laurie Anderson and Maureen Connor, have developed their artistic practices to use the body to explore both the female condition and the effects of technology. Other younger artists have filmed and photographed their bodies and placed them on social media; artists such as Petra Cortright and Amalia Ulmann utilize Instagram and YouTube to explore female self-presentation online in a way that strongly echoes their feminist Body art predecessors. Contemporary artist Moon Ribas, who considers herself a "cyborg" artist, had an online seismic sensor chip implanted in her elbow that allows her to feel the occurrence of earthquakes through vibration. In her performances, she allows these vibrations to inform her improvisational dance.

The Radical Practices of Body Art Continue

Other artists have recently used the more extreme aspects of body art to make political, sexual, and social statements. For example, in the 1990s, the French artist Orlan began a series of projects to have her face and body surgically altered to resemble Botticelli's Venus, in a bid to draw attention to the double standards and pressure surrounding perceptions of female beauty. Since the early 2000's Chinese Zhang Huan has used his body to depict experiences involving masochistic actions such as sitting in a Beijing latrine nude, covered in honey and fish oil, while flies swarmed across his skin. In 2008, Yale art student Aliza Shvarts caused much controversy by stating that her senior project would consist of a nine-month performance in which she would repeatedly inseminate and then abort herself - an act that was never verified to be true or false after her project was banned by the school from coming to fruition. In 2013 Russian artist Petr Pavlensky sat naked outside the Kremlin and nailed his scrotum to the floor as a protest against Russia's political system. In 2014 at Art Cologne, Milo Moire literally birthed her paintings by standing nude on a platform and ejecting eggs full of paint from her vagina onto a canvas below. The media frenzy surrounding many of these works brings up questions about the personal and ethical responsibilities of artists and whether taboo actions toward the body were appropriate, even in the liberated world of art.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI