Summary of Conceptual Art

Conceptual Art originated in the mid-to-late 1960s, and prizes ideas (concepts) over the aesthetic and commercial properties of artworks. An blend of various tendencies rather than a tight, unified, movement, Conceptual Art took on myriad forms, including installations, performance art, and/or happenings, that tested the boundaries of and attitudes toward art. Conceptual artists often produced works (and treatises) that critiqued many of the underlying ideological structures that affect the production, exhibition, criticism, and distribution of fine art.

The abiding complaint aimed at Conceptual Art, however, is that it is elitist; that it is beyond the intellectual reach of the general public and is appreciated only by a "clique" of artists, collectors, gallerists, and curators. There is a degree of legitimacy to this argument. But Conceptual artists are essentially asking their audience - be they converts or skeptics - to question the very essence and function of art.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Conceptual artists recognize that all art is essentially conceptual. But in order to emphasize this fact, many Conceptual artists reduced the material presence of the work to its absolute minimum - a tendency that some have referred to as the "dematerialization" of art.

- It is helpful to draw a line between Conceptualism and Conceptual Art. The latter is a self-defined movement originating around the mid-1960s, whereas Conceptualism has a history almost as long as modernism itself. The forefather of Conceptualism is, by almost universal agreement, Marcel Duchamp. His Dadaist readymade sculpture, Fountain (1917), an upturned urinal that he signed and displayed in an American gallery (thereby presenting it as art) established a precedent for self-critical art that had no interest in aesthetic beauty and/or skill.

- Conceptual artists were influenced by the reduced simplicity of Minimalism, but grew to reject Minimalism's preference for the conventions of sculpture and painting as mainstays of artistic production. For Conceptual artists, art need not look like a traditional work of art, or even take on a physical form at all (as was the case with those who reduced art to the display of written words, or a performative act).

- Many Conceptual artists followed the ethos that, if the artist began the artwork, then the museum or gallery and its audience should complete it in some way. This sub-category of Conceptual Art, known as institutional critique, can be understood as part of the wider shift away from the object-fixated art towards art that asked its audience to consider it on their own terms and in relation to wider societal and cultural values.

Overview of Conceptual Art

One of the main theorists of Conceptual art, Sol Lewitt said "Ideas alone can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form. All ideas need not be made physical." He conceived many different pieces, some were never built, while others were ultimately given physical form.

Artworks and Artists of Conceptual Art

Erased de Kooning Drawing

In 1953 Robert Rauschenberg visited Willem de Kooning's loft, requesting one of de Kooning's drawings to completely erase it. Rauschenberg believed that in order for this idea to become a work of art, the work had to be someone else's and not his own; if he erased one of his own drawings then the result would be nothing more than a negated drawing. Although disapproving at first, de Kooning understood the concept and reluctantly consented to hand over something that he (de Kooning) would miss and that would be a challenge to erase entirely, thus making the erasure that much more profound in the end. It took Rauschenberg a little over a month and an estimated fifteen erasers to "finish" the work. "It's not a negation," Rauschenberg once said, "it's a celebration, it's just the idea!" Of course, it also signaled a farewell to Abstract Expressionist art, and the expectation that a work of art should be expressive. The absent drawing is a Conceptual work avant la lettre, and a precursor to works like Sol Lewitt's Buried Cube Containing an Object of Importance but Little Value (1968), a gag piece, where LeWitt supposedly interred a simple cube in a collector's yard, and with it he buried Minimalism's object-centered approach.

Charcoal, pencil, crayon and ink drawing by Willem de Kooning, erased - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II (Black Painting)

As part of MoMA's Sixteen Americans exhibition of 1959, Frank Stella caused nothing short of a sensation with his "what-you-see-is-what-you-see" canvases. His Black Paintings (soon followed by his Copper and Aluminum series, all produced between 1959-62) embodied Stella's audacious proposition that a painting should be stripped of everything except its own presence as a physical object, and therefore devoid of any reference outside the work/object itself.

MoMA explains how Stella "applied enamel paint directly onto the canvas to create two seemingly identical sets of black stripes, each the width of the housepainters' brush used to produce it, interspersed with lines of unpainted canvas. The picture's two-dimensionality is emphasized by the symmetrical composition, a device Stella used in all his [twenty-three] Black Paintings to subvert spatial illusion." Stella himself said of the work, "My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there. It really is an object. . . All I want anyone to get out of my paintings, and all I ever get out of them, is the fact that you can see the whole idea without any confusion ... What you see is what you see." Stella's Black Paintings set the stage for the emergence of the Minimalist movement.

Oil on canvas - MoMA, New York

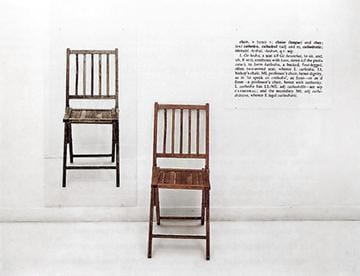

One and Three Chairs

A physical chair sits between a scale photograph of a chair and a printed definition of the word "chair." Emblematic of Conceptual art, One and Three Chairs makes people question what constitutes the "chair" - the physical object, the idea, the photograph, or a combination of all three. Joseph Kosuth once wrote, "The art I call conceptual is such because it is based on an inquiry into the nature of art. Thus, it is...a thinking out of all the implications, of all aspects of the concept 'art.'" One and Three Chairs denies the hierarchical distinction between an object and a representation, just as it implies a conceptual work of art can be object or representation in its various forms. This work harks back to and also extends the kind of inquiry into the presumed priority of object over representation that had been earlier proposed by the Surrealist René Magritte in his Treachery of Images (1928-9), with its image of a pipe over the inscription "Ceci n'est pas un pipe" (This is not a pipe).

Wood folding chair, mounted photograph of a chair, and photographic enlargement of a dictionary definition of "chair" - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Vertical Earth Kilometer

The idea underlying this piece was the creation of an actual yet invisible work of art. With the help of an industrial drill, De Maria dug a narrow hole in the ground exactly one kilometer deep, inserted a two-inch diameter brass rod of the same length, then concealed it with a sandstone plate. A small hole was cut in the plate's center to reveal a small portion of the rod, which is perfectly level with the ground. The result is a permanent work of art that people are forced to imagine but may never actually see. As a complementary piece to Vertical Earth Kilometer, De Maria created the far more visible Broken Kilometer (1979), which consisted of five hundred two-meter-long brass rods, neatly arranged on an exhibition floor space in five parallel rows of one hundred rods each. In keeping with Conceptual artists' dispensation of traditional materials and formal concerns, this work defies the marketplace: it can't be sold or entirely exhibited. Further, its simplicity and largely concealed quality makes it anti-expressive and consistent with the period's many paradoxical negations of the visual in "visual art."

One-kilometer-long brass rod, red sandstone plate - Friedrichsplatz Park, Kassel, Germany

Grapefruit

Yoko Ono's extremely plain-looking and oddly titled book, Grapefruit, first released in 1964, is an important early example of Conceptual art and of the link between it and Fluxus. Although the work, technically speaking, is an object, the art extends beyond its material constraints as it contains a series of artistic "event scores" - various instructions for readers to carry out, if they so choose. Listing some 150 sets of instructions divided into five sections (Music, Painting, Event, Poetry, and Object), Grapefruit acts as something of a user's manual in the Fluxus tradition with a perspective similar to Joseph Beuys's that "every human being is an artist." This book not only subordinates the importance of the physical object to the document or springboard for artistic practice, but also allows for execution of the works by anyone, potentially resulting in an infinite number of artworks stemming from one source. As with other Conceptual works, however, whether the instructions are in fact carried out is of little importance, as the artistic idea is paramount.

Book - First edition of 500, Wunternaum Press, Tokyo

Every Building on the Sunset Strip

For this photographic survey of Los Angeles' Sunset Strip, Ruscha rigged a camera to the back of a pick-up truck and drove back and forth along the strip, shooting both sides of the avenue. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art. The book constituted a significant redefinition of the traditional artist's or photographer's book, expensively bound to highlight the quality reproductions inside.

Much of the history of photography was the attempt to validate photography as an art form, as exemplified by the work of Alfred Stieglitz or Edward Weston. Ruscha did not attempt to glorify the art of photography as one might expect through his abstraction of the subject matter via interesting cropping, careful editing or rich contrasts of light and dark. He does not promote his skill as a photographer. In fact, he shot at high noon under stark lighting that gave the photographs an amateurish look; and instead of artfully composing the picture he used the "strip" rather like a ready-made form to which his artistic decisions were subject. Like many of his generation, he rejects the idea that art should be an expression of a unique artistic vision or personality. Ruscha's frank or "deadpan" document is typical of the anti-expressionist attitude that is seen in much art photography from the 1960s to the present, such as that of Bernd and Hilla Becher, Thomas Struth, and Rineke Dijkstra. A major distinction between photo-conceptualist work and many other instances of what has come to be termed as "deadpan photography" is that the photo-conceptualist approach is documentary (or seems so) and privileges the concept over the presentation of skilled photographic technique.

Photography, accordion fold book - Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, Financial Section

In 1968 Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers opened his Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles as an impermanent conceptual museum that would appear as installations in "sections" at various times and locations between 1968 and 1971. In 1970-71, stressing the economic functioning of cultural institutions, Broodthaers declared the Museum's bankruptcy; he made a corresponding Financial Section through which he tried to raise funds with the sale of specially cast gold bars, or ingot. Stamped with an eagle (the symbol for power and victory, and one he had explored in a previous incarnation of his Museum), Broodthaers set the price of each gleaming bar at double the going market value of gold - thus shifting it from valuation in one market (commodities) to another (art). The bars were valued quite highly as art, which is as much an object as an investment. The gold bar's increased value demonstrated that value of gold and commodities is speculative and market-driven. As Duchamp had indicated before with his Readymades, art has no specific essence or quality other than it being chosen or nominated by an artist, and then also accepted as art by the artistic establishment, which includes the art market. Broodthaers makes this quite clear by "transforming" the gold into art by virtue of the context of his fictional museum. Through the purchase of the Broodthaers ingot, the buyer would help seal the deal that it was a valid work of art and not just gold. The artist/curator/museum director (Broodthaers) would authorize the artwork (the ingot) with a letter of authenticity issued to the buyer. Due largely to the Museum series, Broodthaers is known as an artist involved in "institutional critique," yet it is important to note that this critique is not simply a negation or dismissal of the art world. Rather, it takes the form of a consistent illumination, often through subtle parody, of the interdependency of the artist, the work of art, and the institutions that exhibit and publicize them.

Gold bar stamped with eagle - Galerie Beaumont, Luxembourg

MoMA Poll

For the Museum of Modern Art's 1970 exhibition Information, Haacke conceived of a questionnaire in which museum visitors would be invited to vote on a current sociopolitical issue and submit their answers via written ballot, and deposited in one of two transparent boxes, allowing people to approximate the quantity of submissions. The poll asked, "Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon's Indochina Policy be a reason for your not voting for him in November?" This question, which was not revealed to the museum before the opening of the show, drove at the heart of MoMA as an institution since Governor Rockefeller was a major donor to the museum as well as a board member. There were visibly twice as many YES ballots as NOs, making the result all the more striking given the location and context of the poll itself. Haacke's MoMA Poll is a key early example of Conceptual art's politically motivated vein of institutional critique, and should by no means be mistaken for an impartial survey. Set in motion by the artist, the work had an unforeseeable conclusion, and was only completed by the audience. In this way, Haacke emphasizes that it is not just up to the artist to make a work of art. All works of art are dependent on a consensus for their validation as works of art (a museum purchases a work and validates it, a collector collects it, a publisher makes it "art" by promoting it as such in a magazine or a book about art.) This work demonstrates the belief that artistic production is in fact a collective, not an individual, process.

On-site installation - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Imponderabilia

For Imponderabilia, Marina Abramovic and her longtime partner Ulay face each other, completely nude, and flank the entrance of the museum, obliging visitors to turn and squeeze through the nude bodies to enter. While the piece is obviously designed to draw immediate attention to the performers' nudity, the real concept at work is the exploration of the public's reaction; to the nudity, the performers' placement, and most importantly, the way in which individual visitors choose to enter. Do they appear demure or embarrassed while entering? Do they opt to face Abramovic or Ulay while passing through? Do they choose to enter the museum at all? Abramovic and Ulay carry out their concept in the most dispassionate manner possible, thus leaving expression (commonly considered an artistic aim) to the visitors. The resulting photographs and video of the performance act as something of a study in human behavior when faced with something truly strange, even stressful. Their work demonstrates the kinship between what are usually separated out as distinct trends - Performance art and Conceptual art - but it also distinguishes itself from much Conceptual art in its constant reference to the body, to risk, and the tension between the artists' clinical disinterest and the potential for strong emotional response to the work.

Site-specific performance - Galleria Communale d'Arte Moderna, Bologna, Italy (original performance)

Two Correlated Rotations

Dan Graham began experimenting with the moving image and 360-degree topographical orientation in the mid-1960s, and for Two Correlated Rotations, he conceived of a highly complex exercise involving two performers. This piece, according to Graham, "relate[s] perception to perceived motion and to the perception of depth/time." One performer (Graham) stood inside a designated circle or enclosed space, while another stood outside, and simultaneously each performer followed a predetermined circular path, taking continuous photographs of each other while they moved. The resulting 8-mm film Two Correlated Rotations placed viewers in the mind's eye of the photographer, all while disorienting the viewer by placing this eye in divergent 360-degree rotations. The double synchronous films, screened as a single piece, and the photographic documents call the viewers' attention to a task that took a particular form, but which produced quite different visual representations of that artistic idea. The making of the film is "mirrored" by each camera and thus carries on the modernist tradition of self-reflexivity. Conceptualism's approach is to embrace various media: the project is a film about its own making, but it clearly also relied on live performance, and various non-moving images and diagrams to reveal the artist's concept.

Still from 8 mm film, performance - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Beginnings of Conceptual Art

Fluxus and Minimalism to Conceptualism

While the late 1950s witnessed modern art's progressive shift from Abstract Expressionism to Neo-Dada and Pop Art, the late 1960s witnessed a similar shift, only this time from Fluxus and Minimalism to Conceptualism. The Fluxus artists (one of whom, Henry Flint, was already using the term "concept art") began in the early sixties, and had many affinities with Dada. Embracing "flux", or change, as an essential element of life, Fluxus artists aimed to integrate art and life, using found objects and sounds, simple activities, and situations as stimuli. Joseph Beuys, George Maciunas, Allan Kaprow, Yoko Ono, and John Cage were all associated with Fluxus art.

In the late 1950s, Frank Stella unveiled the first of his series of Black Paintings. With these pieces, Stella's aim was to promote the idea that the artwork/canvas was an object in itself; an "anti-form" that declared that art is nothing more than "what you see" in front of you. Stella's intervention pointed the way forward for Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Robert Morris and other Minimalist artists who emerged in the mid-1960s. The Minimalists embraced abstract repetition, formal simplification, and industrial fabrication in their artworks. They rejected much that was traditional by creating works that occupied space differently, often on a scale too large for a pedestal or home, and usually made of non-traditional artistic materials like bricks or sheets of steel (often the production of these works was outsourced). A number of avant-garde artists bought into the idea that art should be dependent chiefly upon the object/work itself, and that it could therefore exist as an idea or "concept" on its own terms.

LeWitt's “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”

In 1967, artist Sol LeWitt published "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art" in Artforum (considered by many to be the movement's manifesto), in which he wrote: "In Conceptual Art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a Conceptual form in art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art." The idea of placing concept before object, and the value of realization over any aesthetic concerns, directly contradicted the theories and writings of influential formalist art critics like Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried. Their writings, which rather focused on the examination of objects, materials, colors and forms, had helped to define the aesthetic criteria of the preceding generation of artists.

Wiener's “Declaration of Intent”

LeWitt's ideas were expanded on a year later by American Conceptual artist, Lawrence Weiner in his 1968 manifesto, "Declaration of Intent." Weiner declared that he would cease the practice of creating physical art since there was no need to build something when the idea behind the work could suffice. He wrote:

"1. The artist may construct the piece.

2. The piece may be fabricated.

3. The piece need not be built.

Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership."

Wiener's manifesto was published in his first book, Statements (1968), and it effectively passed the responsibility of comprehending the work from the artist onto the viewer. Statements consisted only of written descriptions of sculptures, their materials, and their relationships to space and structure. His ethos was that viewers could just as easily experience the artistic effect by reading a description of the work, and as such, the Conceptual artwork could exist in the world without even being physically constructed.

The Formation of Conceptual Art Movements

Conceptual artists were a disparate, international group, harboring many different ideas about the role of contemporary art. But by the late 1960s it was evident that a loose movement was coalescing in New York. In 1967, Joseph Kosuth organized the exhibitions Non-Anthropomorphic Art and Normal Art in the city. They featured works by Kosuth and compatriot, Christine Kozlov. In his exhibition notes, Kosuth announced: "The actual works of art are the ideas." The following year, a series of Conceptual Art exhibitions, put together by the New York dealer and curator Seth Siegelaub, further promoted the idea of the emergence of a cohesive movement. In 1969, New York's Museum of Modern Art brought together a number of Conceptual artists for an exhibition titled Information. This event was greeted with not a little degree of ironic skepticism given that Conceptual Art was itself critical of the institutional museum system and its market-driven interests.

Art & Language

In Europe, meanwhile, England's Art & Language Group were formulating their own Conceptual ideas. The first incarnation of the Group was formed by Terry Atkinson, Michael Baldwin, David Bainbridge, and Harold Hurrell in Coventry in 1967-68. Writer of the journal Art-Language (first published in November 1969) offered an outspoken attack on modern art and marketing, and especially what they saw as its near total dependence on commercial imperatives. Over the following years many would become members of the group. In 1972, the group produced the Art & Language Index 01 for the Documenta V exhibition, in Kassel, (West) Germany. The installation consisted of a group of eight filing cabinets containing 87 texts from the Art-Language journal. It was perhaps the last hurrah of the first phase of the group which subsequently lived on in the Anglo-American journal The Fox (discontinued in 1976).

Artist Collectives in Other Parts of the World

Conceptualism was not restricted to the US and England. It was also explored widely across other parts of the globe. In Italy, Arte Povera, a term coined by art critic Germano Celant in 1967, was applied to a group of Conceptual artists who critiqued the values of established state institutions of government, industry, and culture. In France, and coinciding with the 1968 student uprisings, Daniel Buren was creating art that formed a critique the institutionalization of contemporary art. Buren's aim was to direct attention away from the work itself and onto the context in which it was being displayed. In the Soviet Union, meanwhile, art critic Boris Groys labelled a group of Russian artists active in the 1970s "the Moscow Conceptualists" or "Russian Conceptualists". The movement began with the Sots art of Komar and Melamid and continued as a subversive trend in Russian art well into the 1980s with artists experimenting in a wide range of media, including painting, sculpture, performance, and literature.

Other international collectives were similarly political in their focus. The Canadian group General Idea had a small membership of three artists, Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal, and AA Bronson, who embraced ephemeral works and installations. Active from 1967 to 1994, their works addressed such themes as the pharmaceutical industry and the AIDS crisis. In Latin America, Brazilian artist, Cildo Meireles, came back to the idea of the "readymade" with his Insertions into Ideological Circuits series (1969). He would appropriate objects in widespread circulation, such as bank notes and Coca-Cola bottles, which he stamped with political messages and then returned into the system from which they came. Later, the Chilean group CADA (Art Action Collective), and the Peruvian group Parenthesis, continued to use Conceptualism as a method of political critique.

Conceptual Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Conceptual Art was conceived as a movement that extended traditional boundaries, and hence it can be difficult to distinguish self-conscious Conceptual Art from the various other developments in art of the 1960s. Conceptualism could take the form of tendencies such as happenings, performance art, installation art, body art, and earth art. The principle that united these developments, however, was the rejection of traditional ways of judging works of art, the opposition to art being a commodity, and the conviction that Conceptual Art could/must exist outside these forces. Because it circumvented aesthetics, it is difficult to define Conceptual Art on stylistic grounds other than a delivery that seems objective and unemotional. While a Conceptual work may possess no particular style, one could say that this everyday appearance and this diversity of expression are characteristics of the movement.

Art as Idea

Among the first to pursue the notion of idea-based art to its logical conclusion was Joseph Kosuth, who evolved a highly analytical model premised on the notion that art must continually question its own purpose. Advocating his ideas most famously in a three-part essay entitled "Art after Philosophy" (1969), Kosuth argued that it was necessary to abandon traditional media in order to pursue this self-criticism. He questioned the notion that art necessarily needed to be manifested in a visual form - indeed, whether it needed to be manifested in any physical form at all. Many, like Lawrence Weiner, similarly stated the need to relinquish the practice of creating physical works of art. By striving to minimize the materiality of art, artists attempted to remove aesthetic criteria and the commodity status out of the artistic equation.

The art critic Lucy Lippard identified this tendency in the chronicle of Conceptualism in her 1997 book Six Years: the Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. She argued that Conceptual Art evoked dispersal (instead of formation), and voiding (instead of creation), and many of the Conceptual artistic ideas were open-ended propositions that lacked foregone conclusions. However, the American artist Mel Bochner denounced Lippard's book as muddled and arbitrary. Lippard herself later argued that most accounts of Conceptualism were false, with memories and spoken accounts of the actual Conceptual Art events not able to be trusted, least of all by the artists themselves.

Language as Art

Although the use of written text in art was not new by the 1960s - text appears alongside other visual elements in Cubist paintings, for example - artists such as Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, Ed Ruscha, and John Baldessari adopted text as the dominant element of a visual work of art. Unlike their predecessors, this generation of artists had often gained college degrees, which in part accounts for the faith in intellectualism and especially the influence of twentieth century studies in linguistics. Text-based art would often use abstract formulations, often in the form of abrupt commands, ambiguous statements, or just a single word to create associations for the viewer. While first-wave Conceptualists like Weiner and Baldessari remain active today, they inspired younger artists from Jenny Holzer to Tracey Emin to continue word-based practice and to push the boundaries of art and its definitions.

Anti-Commodification and Institutional Critique

If Conceptual Art had a central tenet, it was surely their shared discomfort with the institutionalized state of the art world, as arbiter of "good" vs. "bad" art. The "gatekeepers of taste" had been guided largely by market concerns since the mid-nineteenth century, such that "good" art was marketable, and "bad" art was not. The beneficiaries of this system were a small group of (mostly male and white) artists, and members of an elite social class who sold and collected the work, or who participated in the administration of museums. In the 1960s, there was a sense that if art catered to this world, then it will surely not strive to challenge any status quo, or be avant-garde. Conceptual artists and theorists looked closely at modern art practices and trends during the 1960s and early 1970s, seeking forms of radical theory or aesthetics, but found largely a continuation of abstract, post-abstract and minimalist motifs. "What can you expect to challenge in the real world," wrote Burn in the pages of Artforum in 1975, "with 'color', 'edge', 'process', systems, modules, etc. as your arguments? Can you be any more than a manipulated puppet if these are your 'professional' arguments?"

The late 1960s witnessed the emergence of a form of Conceptualism that has come to be known as institutional critique, practiced by artists such as Hans Haacke, Michael Asher, Daniel Buren, and Marcel Broodthaers. Institutional critique continued the tradition of idea-based art, but usually in the form of installations that implicitly questioned the assumed function of the museum--i.e. preservation and exhibition of masterpieces - by providing a view to its greater role within society at large (e.g. as arbiter of taste, as investor, as tax shelter, and gatekeeper to artistic success). The museum is not a neutral hall for the exhibition of works and education of the public. Rather, it is invested in promoting certain artists, in selecting (and thereby defining) "important" works of art, and in shaping the economic reality that benefits its trustees and the established art world. The inherent complexity of institutional critique is that it was often staged within the very institutions that artists were critiquing. At times, the success of a particular work relied on the participation of viewers, thus demonstrating that the work, like the "art world" includes viewers as well as artists and the institutions that host them. Thus, it is important to note that rather than simply negating or rejecting the institution, these artists often implicated themselves in the very thing/s they were seeking to challenge.

Challenges to Authorship

When Marcel Duchamp nominated a urinal as a work of art and reissued later editions of his readymades, he delivered a blow to the West's collective notion of artistic creativity. In keeping with this model, Sol LeWitt's "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art" advocated the idea that the work need not necessarily be fully "authored" by the artist. This idea of an automated or machine-like execution of the art-idea is symptomatic of Conceptualism at large. For instance, in Vito Acconci's Following Piece (1969), the artist subjected his vision to an outside force: the random movements of strangers that he followed on the street until they disappeared into private space. The parameters of the work (the goal, the documentation method) were decided in advance by Acconci, but the resulting path traversed and subjects (the exact people, number of photographs, specific locations, etc.) occurred based on the decisions made by randomly selected individuals and were thus exempt from Acconci's influence.

This denial of the artist as "master" and sole creator of the work also translates to many posthumous works with which an artist's name is associated, but where he/she is not the fabricator. LeWitt in particular (who passed away in 2007) was survived by a number of unrealized sketches for sculptural and other works of art, which to this day are often created anew by teams of fabricators and assistants, thus allowing new LeWitt works to be made even though the artist is no longer able to play his or her part in the production process. Such fabrication in the name of the artist echoes prior modern art practices, particularly in sculpture (the estate of Auguste Rodin is a well-known example of posthumous artistic production). While authorship is, strictly speaking, a component of LeWitt's posthumously-issued works, the practice flies in the face of traditional notions of craft and mastery.

Later Developments - After Conceptual Art

Although the model of Conceptual Art promoted by Joseph Kosuth and Art & Language might be seen as the epitome of the movement - others explored avenues that were arguably just as influential. Conceptual Art sidestepped conventions of craftsmanship and style to an extent that it could be said to place renewed emphasis on content, which had been largely banished under critical emphasis on form. Emergent during a period of major social upheaval, Conceptualism's central tenet - that the idea is paramount - found broad application by artists wishing to emphasize diverse social issues.

Conceptual Art was not a populist form and had limited appeal outside of the art world due to its arcane perception. Furthermore, fractures began to develop in the movement by the mid-1970s, leading to its dissolution. Yet, Conceptualism became inspirational to next-generation artists, many of whom challenged the material basis of art and the language of visual culture. Conceptualism in contemporary practice is in fact often referred to as Post-Conceptual Art and/or Neo-Conceptual Art.

The distinction is rather subtle since a given work can exist in both or either categories. However, the two can be defined as different historical periods. Post-Conceptual Art originates in the mid-1970s and is applied to all art that was influenced by the Conceptual Art movement. Post Conceptual art can describe oil painting, wood sculpture, photography, graphite drawing, and installation art. Neo-Conceptual Art originated in the 1980s and stretched into the 1990s. It refers to all conceptual installation artworks since the dissolution of a Conceptual Art movement.

For instance, photographers associated with the Pictures Generation, namely Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Sherrie Levine, and Barbara Kruger, use the traditional medium of photography, but the foundations of their work, which form strident critiques of topics such as originality, gender, and consumer culture, are strongly conceptual. Someone like the British-Indian sculptor Anish Kapoor, on the other hand, fits more conveniently into the Neo-Conceptualist category. Kapoor's works carry strong conceptual undercurrents that touch on metaphysical ideas such as the coexistence of absence and presence. His monumental, Installation View (2020), for instance, uses convex or concave biomorphic forms of polished steel as way of bringing "the sky down to the earth". Someone like Tracey Emin, however, would fit both categories (although she herself dismissed the use of the terms). Her My Bed (1998), a readymade sculpture featuring her own bed and various items of detritus relating to (amongst other things) her sexual proclivities, her excessive alcohol consumption, and her eating habits, is a wholly autobiographical work that lays bare her inner self for all to see.

Useful Resources on Conceptual Art

- Conceptual Art A&I (Art and Ideas)Our PickBy Tony Godfrey

- Conceptual Art: A Critical AnthologyBy Alexander Alberro, Blake Stimson

- Conceptual Art (Themes and Movements)By Peter Osborne

- Conceptual Art (Basic Art S.)By Daniel Marzona

- Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972Our PickBy Lucy R. Lippard

- Conceptual Art (Movements in Modern Art)By Paul Wood

- Conceptual Art and the Politics of PublicityBy Alexander Alberro