Summary of Neo-Plasticism

Neo-Plasticism, articulated most completely by Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, relied on the most basic elements of painting - color, line, and form - to convey universal and absolute truths. Mondrian advocated for the use of austere geometry and color to create asymmetrical but balanced compositions that conveyed the harmony underlying reality. As with many avant-garde styles of the early-20th century, a utopian vision of society underlay Neo-Plastic theory. Embracing the elemental forms of composition and the merging of painting and architecture, Neo-Plasticism strove to transform society by changing the way people saw and experienced their environment.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Instead of representations of natural forms, Neo-Plasticism relied on the relationships between line and color to emulate the opposing forces that structured nature and reality. Neo-Plastic compositions juxtapose horizontal and vertical lines along with the primary colors of red, yellow, and blue against the non-colors of black, white, and grey to produce timeless balance.

- Neo-Plasticism abolished the figure-ground dichotomy by using an irregular grid structure that resisted arranging the pictorial elements into a hierarchy. This all-over composition created a unity that Mondrian felt underscored the disharmony of the surrounding environment.

- Mondrian and other Neo-Plastic artists thought that the merging of painting, architecture, and design would hasten the coming of an ordered and harmonious society. They intended that this utopic vision, coming from the "dynamic equilibrium" sought out in Neo-Plastic paintings, would spread to the interior of the studio, to the home, the street, and the city, and eventually to all of the world.

Artworks and Artists of Neo-Plasticism

Composition with Color Planes 5

By 1917, Mondrian had abandoned any allusions to representations of nature, and this work is among the first group of paintings to embody the ideas that he put forth in "Neo-Plasticism in Painting," published in the same year. In previous work, like Pier and Ocean (1915), Mondrian used only black and white lines on a white background to depict a very abstracted landscape. According to Mondrian, "Vertical and horizontal lines are the expression of two opposing forces; they exist everywhere and dominate everything; their reciprocal action constitutes 'life'."

The ochre, mauve, and grey rectangles cover the surface of the painting in an asymmetrical fashion, subverting the regular grid format. While the rectangles seem to float above the white background, close inspection reveals that the "background" itself consists of painted white rectangles. Without inscribing lines on the painting, these white rectangles of varying size hold the others in place. Mondrian wrote to a friend that paintings similar to this one "represent a development which I believe offers a better solution for color planes against a background. As I painted, it gradually became clear to me that for my work color planes set against a solid field do not form an entity." By setting the colored blocks amidst white ones, Mondrian created a tightly interlaced, united composition.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Composition

In this geometric abstract work, six rectangles in varying sizes are depicted in pairs of primary colors - red, blue, and yellow - against a white background. Two short horizontal lines float at the upper right and lower left corners, and three short lines create a broken diagonal from the lower right to upper left corners.

This work is one of Van der Leck's few completely abstract paintings. Prior to meeting Mondrian in 1916, his work included figurative elements, but in the following association with Mondrian, he began using line and geometric form to create abstract works. He was one of the co-founders of the magazine, De Stijl, and for a time collaborated with the group. Eventually, he came to disagree with Mondrian and the others about the representational aspects of art. Van der Leck used the geometrical elements of Neo-Plasticism to create recognizable images, as can be seen in his Man te paard (The horseman) of 1918.

It is possible that even this abstract composition could have begun as a vase of flowers on a table, but after deconstructing the image to its most elemental forms, we are left with a seemingly abstract configuration of shapes and lines. Notable is the use of the diagonal in the line segments dividing the canvas, and the placement of rectangles to resemble diamond shapes. As a result the overall effect is that the color rectangles create a kind of implicit shape on the canvas, the suggestion of an underlying reality, outlined with a minimalist vocabulary.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Composition With Grid VI

Mondrian turned his usual square format on its edge to produce a diamond-shaped canvas, creating one of the first "lozenge paintings," as he called them. After a period of time when he abandoned line to work only with geometric shapes of color, Mondrian reintroduced line again in 1918 as he continued to develop Neo-Plastic ideas with his fellow artists Theo van Doesburg and Bart van der Leck. Subsequently, he made a number of rhomboid paintings like this one, composed of a grid of rectangles, divided by black lines and painted in rose, grey, yellow, and white.

For Mondrian, the right-angle meeting of lines and planes was crucial for conveying the equilibrium of contrary forces, but he was willing to experiment with whether the same equilibrium could be found in the meeting of diagonals. Art historian Carel Blotkamp suggests that Mondrian painted the composition oriented as a square so that all of the lines would have been diagonal, but after further discussion and consideration with his colleagues, Mondrian reoriented the painting so the lines would be vertical and horizontal.

Heavy black lines divide some of the rectangles, but other lines are lighter, creating an impression of translucent color, and conveying a sense of shallow, not illusionistic, depth on the surface of the canvas. Mondrian said that the lozenge paintings were all about "cutting." The diagonal edge of the diamond-shaped canvas cuts through the vertical and horizontal lines, in effect cropping the composition. The viewer can imagine the grid continuing beyond the edges of the canvas onto the surrounding space, thus suggesting the underlying unity of the world.

Oil on canvas - Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Compositie VII: 'de drie Gratien'

Composed of rectangles of varying sizes and shapes in primary colors and white, Mondrian's Neo-Plastic influence is evident in this early work by van Doesburg. Distinctively, however, he uses a black background, instead of Mondrian's white, and retains an element of the representational, not only in his title, referring to the "Three Graces" of Greek myth, but in the arrangement of the shapes and colors to suggest the motif of the three dancers.

Van Doesburg valued dance, seeing it as ideal form of expressive art that linked to his interest in Hindu spirituality. Unlike Mondrian's strict abstractions, this painting is more expressive. The black background provides a dynamic contrast to the short and long rectangles, creating a sense of movement and rhythm.

Oil on canvas - Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis

Contra-Compositie XIII

Theo van Doesburg here created an all-over, dynamic composition with a number of triangles, painted in red, yellow, black, white and grey. Around 1924, van Doesburg began painting what he called his Counter-Compositions to reflect his theory of Elementarism. Feeling that Neo-Plasticism was too static, he wanted to create more dynamic works, using diagonals placed at 45 degree angles. His ideas caused a rift in his friendship and working relationship with Mondrian in 1925.

The diagonals of the triangles create aggressive intersections, but not all of the triangles are whole, leading the viewer's eye to follow the diagonals off the painting's edge to complete the shapes. While van Doesburg adhered to the Neo-Platonic tenet of "peripheric" composition, which puts the focus on the edges of the canvas instead of the center, his decentered arrangement of forms does not create an equilibrium. Instead, the off-centered edge of the large black triangle and the intersecting point of the red triangle create a constantly shifting sense of balance.

Oil on canvas - Guggenheim Museum, New York

Red and Blue Chair

This chair, designed in 1918 and painted with bold primary colors in 1923 was one of the first instances of Neo-Plastic ideas translated into three dimensions. Its cleanly jointed horizontal and vertical planes make the chair seem to float.

Rietveld hoped to eventually mass-produce the chair and so employed standard sizes of lumber for its construction. He had originally been a cabinetmaker, but as an early member of De Stijl, he began designing furniture, starting his own furniture making company and going on to become an architect. For this work, he developed a new type of joint (now called the "Rietveld joint") that uses dowels so that the vertical and horizontal planes seem to exist independently.

When Bart van der Leck recommended the use of bright primary colors in 1923, Rietveld remade the chair with thinner pieces of wood and then painted it black, red, yellow, blue, and red. In the Schröder House, where the chair was placed against the house's black walls and floors, it seemed to disappear, except for the floating color rectangles. Rietveld was less concerned with the physical comfort and more interested in new forms of furniture to create a sense of spiritual harmony and social order.

Painted wood - Auckland Museum, New Zealand

Rietveld Schröder House

The best-known representation of De Stijl architecture, the Rietveld Schröder House embodies Neo-Plastic form and utopian aspirations. Using lines and planes painted in primary colors, white, black, and grey, Rietveld created an asymmetrical composition in which the interior and exterior of the house are unified.

Rietveld designed and built the home for Mrs. Truus Schroder, a widow and mother of three, whose ideas also shaped the design. Disliking the architect's initial design, she envisioned a space that was endlessly transmutable with walls and partitions that could be moved depending on the time of day and other needs. Additionally, the large windows along with the overlapping planes of the facade that created many balconies allowed the inside and outside to flow together. Schroder "wanted to live in the active sense and not be lived;" that is, she didn't want the activities of raising her children to be confined and determined by the house's structure.

The variety of building materials gives the home visual texture, and the house makes no attempt to blend into the city block. Its innovation is immediately apparent compared to the surrounding structures. Mondrian's goal for Neo-Plasticism was to transform society. He stated, "The pure plastic vision should set up a new society...a society composed of balanced relationships." To this end, the Rietveld-Schröder house is a "pure plastic vision" designed to be the cornerstone of a new vision of society, in which individuals were free to make choices about how they lived and moved in their environment.

Bricks, plaster, concrete, wood, steel girders, iron mesh - Utrecht, Netherlands

Ciné-dancing (cinema-dance hall; also called Grande Salle or Ciné-bal) in L'Aubette

Walking into the Ciné-dancing hall, designed by Theo van Doesburg, one feels enveloped by one of the artist's Elementarist paintings. A grid of variously colored, diagonally inclined relief panels covers the walls and ceilings. These diamonds juxtaposed with the rectangular partitions between the booths, the windows, and the doors, create a visual tension in the space.

Van Doesburg, along with the Dadaists Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp transformed the spaces of the 18th-century Aubette building in Strasbourg after receiving a commission to redesign the interior of the Cafe L'Aubette, a large area that would include a cinema, dancehalls, and a restaurant. Believing in gesamtkunstwerk, the idea of a completely integrated art that carries over into all aspects of daily life, van Doesburg also designed the lettering for the building's various signs and even the ashtrays. This room embodied the new principles of Elementarism that van Doesburg had recently articulated.

The dynamic tension created between the interior's horizontal and vertical design and the painted diagonals suggest a modern liveliness befitting the space's function as a dance hall. The integration of space, color, and movement attests to van Doesburg's desire to merge architecture and painting in order to create a utopian society. Unfortunately, the public did not take to van Doesburg's radical new space, and the artist quickly modified it.

Place Kleber Strasbourg

Composition with Red Blue and Yellow

This minimal composition of thick black lines separating rectangles in varying sizes of pure primary colors and white, exemplifies Mondrian's mature Neo-Plastic style. Reducing the color palette to red, blue, and yellow and contrasting vertical and horizontal lines, Mondrian intended to depict "absolute reality" as a balanced relationship between contrasting forces.

The lines, cut off by the canvas' edges, implicitly extend beyond it, as do the colors of the rectangles. Upon closer examination, the lines themselves are of varying thickness, making them less like outlines and more like smaller counterparts to the abutting planes. This asymmetry of planes, creating an irregular grid, evokes a balanced tension. Despite the simplicity of the composition, the surface of the painting is not without visual interest, with glossy black lines next to the more thickly painted white rectangles with ever-so-slightly visible brushstrokes. Mondrian created relationships between forms, colors, and textures, which he ultimately understood to underlie the harmonious relations between people, objects, and their environment.

Oil on canvas - Kunsthaus Zurich, Switzerland

Victory Boogie Woogie

Unfinished at the time of his death in 1944 and posthumously titled, this dense, brightly colored painting embodies Mondrian's love of New York City and American jazz, which he experienced at the end of his life. Jettisoning black lines and returning to the diamond-shaped support, Mondrian built up a composition of smaller and larger planes of primary color that creates a dazzling, even dizzying, sense of movement that contrasts with his previous, more austere canvases.

Mondrian made this work by first creating a grid of uniform, color lines that he subsequently divided with other planes of color. In the 1940s, Mondrian began using strips of colored tape to adjust and recompose his works. At one point he felt this painting was finished, but then unhappy with the result, he began using the colored tape, which is still in place on the canvas, to modify parts of the composition. While still not satisfied with his resolution, Mondrian wrote to the art historian James Johnson Sweeney in 1943 explaining that he felt he had landed upon new compositional possibilities with the destruction of lines.

With its lozenge form and its over 600 planes of color, the work is incredibly dynamic. The overall effect is of a vital and energetic multiplicity, a sequence of constantly varying relationships that conveys a sense of infinite possibilities within the (altogether finite) limitations of the pictorial frame.

Oil, tape, paper, charcoal and pencil on canvas - Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (The Hague), Amsterdam, Netherlands

Beginnings of Neo-Plasticism

Mondrian's Neo-Impressionism and Theosophism

From 1909-1910 Mondrian painted in a Neo-Impressionist style and carefully studied Georges Seurat's scientific methodology and color theory that emphasized the use of contrasting primary colors. During this time, he also joined the Dutch Theosophical Society and remained a member all his life. The writings of the theosophists Madame Blavatsky, Rudolph Steiner and M. H. J. Schoenmaekers's Beginselen der Beeldende Wiskunde (The Principles of Plastic Mathematics) both influenced and echoed the aesthetic theory that Mondrian was then developing. Particularly influential was Schoenmaeker's view that, "The two fundamental and absolute extremes that shape our planet are: on the one hand the line of the horizontal force, namely the trajectory of the Earth around the Sun, and on the other vertical and essentially spatial movement of the rays that issue from the center of the Sun...the three essential colors are yellow, blue, and red." The use of horizontal and vertical lines and primary colors became fundamental principles of Neo-Plasticism. Mondrian even borrowed one of Schoenmaeker's phrases, "de nieuwe beelding," which literally means "new image creation" or "new art," as the name for his new art style.

The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875 by Madame Blavatsky, took for its motto, "There is no Religion higher than Truth." Blavatsky felt that universal truth was a harmony achieved by balancing the relationships between opposing dualities. Saying, "I recognized that the equilibrium of any particular aspect of nature rests on the equivalence of its opposites," Mondrian viewed pictorial elements, like horizontal and vertical lines as opposites. By creating relationships between them he could reflect, not a representational view of natural form, but the essence of reality.

In 1911 Mondrian moved to Paris, motivated by an interest in Cubism, after seeing an exhibit in Amsterdam that included paintings by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. While in Paris, building upon the Cubist fragmentation of form and underlying grid system, he began to develop what he called "abstract cubism," as reflected in his painting Composition in Blue, Grey, and Pink (1913). In 1914, Mondrian travelled back home to the Netherlands, but the outbreak of World War I made it impossible for him to return to Paris. In the Netherlands, he began using fewer colors and a narrower range of geometric forms. He also became friends with the painter Bart van der Leck, an association that was influential for both men, as Mondrian was influenced by van der Leck's use of areas of primary color and van der Leck by Mondrian's abstraction.

Neo-Plasticism and De Stijl

These conversations and engagements with his Dutch colleagues led Mondrian to articulate his new aesthetic theory, Neo-Plasticism, in 1917. In the preceding years, Mondrian strived to create an art that eschewed natural representation and reflected what he called, "absolute reality." Neo-Plasticism brought together his previous artistic preoccupations, including Neo-Impressionism and Cubism, and his spiritual beliefs as a theosophist.

That same year Dutch painter and critic Theo van Doesburg, along with Mondrian, Bart van der Leck, and Vilmos Huszár founded the magazine De Stijl, Dutch for "The Style," a phrase used as a label for the group of artists. De Stijl became largely synonymous with Neo-Plasticism until approximately 1926.

Van Doesburg first encountered Mondrian's work while working as an art critic reviewing a 1915 exhibition. Feeling that the Mondrian's abstract painting embodied an artistic ideal that he also was striving toward, he contacted Mondrian. A mutually influential relationship developed. With his extroverted and energetic personality, van Doesburg became the group's leader and promoter, while Mondrian, philosophical and introverted, was the theoretician, deeply committed to the practice of abstract geometric art. The first issue of De Stijl appeared in October 1917, and the first twelve issues included installments of Mondrian's essay Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art.

Other early members of the group De Stijl who adopted Neo-Plasticism's principles were the artists Anthony Kok and Georges Vantongerloo and the architects J.J.P. Oud and Gerrit Rietveld.

In 1926 Theo van Doesburg broke with the strict tenants of Mondrian's Neo-Plasticism and developed his own aesthetic theory, Elementarism, to articulate the goals of his new art, which increasingly used diagonal lines instead of horizontal and vertical ones. Many artists belonging to the De Stijl group followed van Doesburg's lead, adopting diagonals into their work. With van Doesburg's death in 1931, both Elementarism and de Stijl came to an end. Splitting from De Stijl in 1925, Neo-Plasticism continued as a movement, independent of De Stijl, as Mondrian, first in Paris and then in New York, brought new artists to the style.

Neo-Plasticism in Paris (1919-38)

In 1919 Mondrian moved to Paris, and, though he remained a part of De Stijl and continued to show with the group, he became increasingly independent in his evolving development of Neo-Plasticism. He began painting his first "lozenge" paintings, where a square canvas, tipped on its edge, resembled a diamond shape, as can be seen in his Composition With Grid VII (1919). The following year he published his book, Neo-Plasticisme (Neo-Plasticism) in Paris, which gave De Stijl a renewed impetus, reaching a wider European audience. His sense of the work's importance is reflected in his hope that Neo-Plasticism would be recognized as the artistic expression of theosophism. He sent a note to the theosophist Rudolf Steiner in 1921, but Steiner's lack of reply led to Mondrian's increasing philosophical independence from official theosophy.

In the early 1920's, Mondrian developed the paintings that became indicative of his mature style of Neo-Plasticism. In these works, such as Tableau with Yellow, Black, Blue, Red and Grey (1923), thicker black lines run to the edge of the canvas, creating rectangles and squares, which Mondrian painted in white or pure primary colors. Rietveld's Red and Blue Chair (c. 1923) and the Rietveld Schröder House (1924) are examples of this mature style of Neo-Plasticism in design and architecture.

By 1925, Neo-Plasticism became independent of De Stijl and became associated with other artists and groups. In 1930 Mondrian showed with Cercle et Carré (Circle and Square) and the group promoted Neo-Plasticism in three issues of its journal. In 1931 he joined Abstraction-Creation, an international group of abstract artists, a number of whom, drawn to Neo-Plasticism's mathematical sparseness, adopted the use of primary colors and horizontal and vertical lines intersecting at a 90-degree angle.

In 1934 the American artist Harry Holtzman spent several months in Paris where he spent much time with Mondrian and, subsequently, created Neo-Plastic paintings, like Square Volume With Green (1936-37). The French artist Jean Gorin, also having met Mondrian, began to practice Neo-Plasticism, as seen in his painting, Chromoplastique architecturale (1930).

Neo-Plasticism in London (1938-40) and New York (1940-44)

The rise of Fascism in France caused Mondrian to leave Paris in 1938 for London, where, full of uncertainty, he left a number of works unfinished but continued to develop the Neo-Plastic vocabulary. He added many more thin black lines to his compositions, creating an overlapping effect, and experimented with color lines. When Paris fell to the German army in 1940, he left Europe altogether, settling in New York City where he lived until his death.

In New York, Mondrian felt a renewed sense of energy and vitality; he loved the city, and the works he created there were his most innovative. He began using overlapping thin lines, bright with color and a sense of the city's liveliness, as can be seen in his painting New York (1942) and his most well-known work from this time, Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-1943). Inspired by his love of jazz and of Manhattan, the work's many rectangles, created by thin yellow lines that shimmer with small squares of color, are a bustling dynamic grid.

American artists, including Ilya Bolotowsky, Harry Holtzman, Leon Polk Smith, Charmion Von Wiegand, and Sidney Jonas Budnick took up Neo-Plasticism. Von Wiegand interviewed Mondrian in 1941, and he encouraged her to pursue her dream of becoming an artist. The two began an artistic friendship, as she translated many of his essays into English while developing her own Neo-Plastic art. She later joined the American Abstract Artists Group where she became an active leader, promoting abstract geometric art.

Neo-Plasticism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

While Neo-Plasticism found its beginning in painting, it gained adherents in the realms of sculpture, architecture, and all aspects of design. The movement's only closely related alternative was Elementarism, which shared the same sense of an all-encompassing aesthetic that could be applied in all art and design fields.

Neo-Plasticism and Graphic Design

The principles of Neo-Plasticism became widely practiced in graphic design and typography. Every issue of De Stijl magazine embodied Neo-Plastic design, as reflected in the first cover designed by Vilmos Huszár. Fitting each letter into the shape of a square, Theo van Doesburg created a new typographical alphabet to be used for posters, book and magazine covers, and signage. He created posters, like the one for the 1920 International Exhibition of Cubist and Neo-Cubists, and all the signage for the Cafe l'Aubette. Throughout his career, Bart van der Leck designed a number of posters, including a well-known commercial poster for Delf Salad Oil Factories (1919). In another famous piece, Van Doesburg and László Moholy-Nagy designed a book cover for Bauhaus Bucher 6 that was meant to exemplify Neo-Plastic design in 1925.

Neo-Plasticism and Sculpture

Mondrian advocated for the connection between painting and architecture, and felt that sculpture and reliefs were a natural progression of painting toward architecture. Perhaps due to this influence, a number of artists, including Georges Vantongerloo, César Domela, Jean Gorin, and Harry Holtzman, who began as Neo-Plastic painters, turned to Neo-Plastic sculpture and making three dimensional reliefs.

Neo-Plasticism's use of horizontal and vertical lines, primary colors, and asymmetry was carried over into sculptures like Vantongerloo's Composition from the Ovoid (1918), which uses horizontal and vertical lines and wood rectangles painted in primary colors. Vantongerloo was to continue developing the Neo-Plastic style in sculpture as can be seen in his 1924 Construction of Volumetric Interrelationships Derived from the Inscribed Square and the Square Circumscribed by a Circle. The sculptor translated the principles of Neo-Plasticism into variations of volume and proportion derived from mathematical formulae.

The sculptor, photographer, artist, and typographer César Domela made three-dimensional reliefs such as Construction (1929), an oil and metal work on panel. He went on to use metal, photomontages, cutouts, and Plexiglas to create sculptural Neo-Plastic works like his Neoplastic Relief #10 (1930). His later work often uses diagonals, reflecting the influence of van Doesburg's Elementarism, though he developed his own individual interpretation by varying the angle at which the diagonals were placed.

While Vantongerloo and Domela were members of De Stijl, Neo-Plastic sculpture was also practiced by artists outside the group. The American artist Holtzman's Sculpture I (1940) and Sculpture (1941-42), made of muslin or cheese cloth, painted in primary colors, and then attached to Masonite, are examples of his Neo-plastic sculpture. Jean Gorin, influenced by Mondrian, moved from Neo-Plastic painting to reliefs that evolved into wall sculptures. Using the pure primary colors on black or white backgrounds, his polychrome sculpture was rare during this era.

Neo-Plasticism and Architecture

From the beginning Neo-Plasticism advocated that its new aesthetic meant that, as Mondrian wrote, "architecture and painting can merge...and can resolve into each other." He went on to say, "While Neo-Plasticism now has its own intrinsic value, as painting and sculpture, it may be considered as a preparation for a future architecture."

Mondrian's own work in carrying the principles of Neo-Plasticism into space led to his creating a theatre backdrop for the play The Ephemeral is Eternal (1926) by the art critic Michel Seuphor. He subsequently used the drawings for a proposed project for Ida Biernet's library in 1926. His design used an open box method of pictorial composition and an orthogonal grid to work out the relationships of color and line.

A number of noted architects created Neo-Plastic buildings. In 1923 Vilmos Huszár and Gerrit Rietveld created their Space-Color-Composition for the Berlin Juryfreie Kunstschau Exhibition, where visitors were guided by color planes and black vertical lines on the wall and floor through two connecting rooms. In 1925, J.J.P. Oud became well-known when the facade he created for the Cafe de Unie in Rotterdam caused controversy with its colored, asymmetric, horizontal and vertical design. That same year in Paris, the Austrian architect, Frederick Kiseler, created his City in Space installation for the International Exhibition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts. The suspended structure was originally meant to be a set backdrop but evolved into a prototype for a new Neo-Plastic city. The most famous example of Neo-Plastic architecture was the 1924 Rietveld-Schröder House, listed as an UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000 and lauded by the committee as "an icon of the Modern Movement in architecture... [that] occupies a seminal position in the development of architecture in the modern age."

Theo van Doesburg wrote, "Architecture as a construction method...synthesizes every function of human life," and felt that stained glass windows were a way of translating painting into architecture, as seen in his Neo-Plastic 1917 Stained-Glass Composition IV, created for the De Lange House in Alkmaar. Throughout his career, he collaborated on a number of architectural and interior design projects, including Oud's Project for a Workers' Housing Complex in Rotterdam from 1920-1923, though many of the projects were never completed. His most notable architectural achievement was with Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp in creating Cafe L'Aubette, where the design embodied Elementarism.

Neo-Plasticism and Interior/Furniture Design

Neo-Plastic artists viewed interior and furniture design as part of the totality of the creation of space. Every element mattered, as reflected in Theo van Doesburg's designing the ashtrays for the Cafe L'Aubette.

The most famous example of Neo-Plastic furniture design was the Red and Blue Chair created by Rietveld in 1923 and placed in the Rietveld-Schröder house. Yet his innovative view of furniture design was met with criticism that his chair was uncomfortable. Rietveld responded to his critics, saying, "You are absolutely right. I hurt my ankles on the bits that stick out. But, on the other hand, it's not really a chair: it's a manifesto." For Rietveld, more important than the chair's function was the way in which the chair structured the space in which it was placed, the chair becoming more of a sculpture, a work of fine art.

Mondrian's own foray into creating a Neo-Plastic space was his studio, a totality viewed as a work of art in itself. Mondrian carefully considered the colors and arrangement of the studio's physical structures as well as the furniture and other objects in the space. He wanted the abstract to become reality, and in order to do so he emphasized the planar aspects of the space instead of its three-dimensionality.

Elementarism vs Neo-Plasticism

Elementarism was a subtype of Neo-Plasticism developed around 1925 by Theo van Doesburg out of a desire to create a more energetic and dramatic geometric art. His Manifesto of Elementarism announced its arrival in the 1926-1927 issues of De Stijl.

Elementarism was the culmination of several earlier influences upon van Doesburg. Promoting De Stijl throughout Europe, he lectured from 1921-1923 at the Bauhaus, and there met El Lissitzky, the Russian Constructivist, whose ideas on combining architecture and art influenced him, as can be seen in van Doesburg's and Cor van Essteren's 1924 essay Towards a Collective Construction. Here, the artists stated, "We have established the true place of color in architecture and we declare that painting without architectural construction...has no further reason for existence." Accordingly, the most important innovations of Elementarism were to be in the combining of painting and architecture, as in the Cafe L'Aubette, where Van Doesburg collaborated with the Dadaists Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp to create a dance hall according to its principles.

During his stay at the Bauhaus, van Doesburg, influenced by the Dada art movement, began using the pseudonym I.K. Bonset and founded the Dada journal, Mecano, when he returned to Holland in 1923. Feeling that new, more dynamic art forms were needed to create a new world following the ruin of World War I, he wrote articles as Bonset critiquing Neo-Plasticism and various De Stijl artists. During this time, van Doesburg's ideas about architecture also began to shift, causing further disagreements with Mondrian. Van Doesburg felt, according to art historian Carel Blotcamp, that his new "'color architecture' was the concrete manifestation of the time-space continuum" and emphasized the experience of the individual as he or she moved through the space.

While Neo-Plasticism emphasized the balance created by the relationship between contrasting vertical and horizontal lines and primary colors, van Doesburg came to believe that "Balanced relationship is not the final result," essentially abolishing Neo-Plasticism's insistence on positive and negative pairs. Van Doesburg wrote, that the essence of Elementarism was "neither left nor right, neither symmetry, nor statics, nor the exclusively Horizontal-Vertical." Elementarism instead advocated the use of diagonals as a way of abolishing these pairs in pictorial terms.

Calling his new works, "Counter-Compositions," van Doesburg thus began using diagonals in his paintings. As a result of van Doesburg's advocacy for diagonals and out of a profound philosophical disagreement with the tenets of Elementarism (especially as they pertained to architecture), Mondrian left the De Stijl group in 1925, and his friendship with van Doesburg came to an end. Some De Stijl members practiced Elementarism, even if temporarily, including Bart van der Leck, the artist Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart, the sculptor Georges Vantongerloo, and the architects Gerrit Rietveld and J.J.P. Oud. Both De Stijl and Elementarism ended in 1931 with the death of van Doesburg.

Later Developments - After Neo-Plasticism

The influence of Neo-Plasticism, extensive in art, architecture, and culture, has often been synonymous with Mondrian, its theoretician and most famous practitioner. As Stephen Bayley, the design historian said, "Mondrian has come to mean Modernism. His name and his work sum up the High Modernist ideal." In its own time, the movement influenced a number of Dutch artists, like Jan Sluijters and Jacoba van Heemskerck, the English artist Marlow Moss, the German Carl Buchheister, and the modernist architects, Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier.

The movement influenced the hard edge painting style of many Americans, as seen in the work of Ellsworth Kelly, and the geometric Op Art of Bridget Riley. Donald Judd, the Minimalist, was influenced by Neo-Plasticism as expressed in his essay, "Some Aspects of Color in General and Black and Red in Particular," and the Abstract Expressionist Ad Reinhardt acknowledged the importance of the movement in his own work. The English artist, Keith Milow, in 2001-2003 made a series of paintings based upon Mondrian's work.

Architecture has continued to be influenced by the movement, as can be seen in Moshe Safdie's Habitat of 1967. The noted architect, Cesar Pelli, designed his 1984 West Wing expansion of the Modern Museum of Art with what has been called "Mondrianesque skin," an exterior of multicolored glass in a Neo-Plastic grid. In 2014 Hiroshi Sugimoto designed his Glass Tea House "Mondrian," shown at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Neo-Plasticism has also had a wide cultural influence. Its elemental design can be easily replicated by graphics software that continues to influence computer program design, video games, and website design. Several programming languages are named after Mondrian, and, since the 1970s, a number of musical groups, including Silverchairs, The Apples in Stereo, and the White Stripes have had album covers in the Neo-Plastic style.

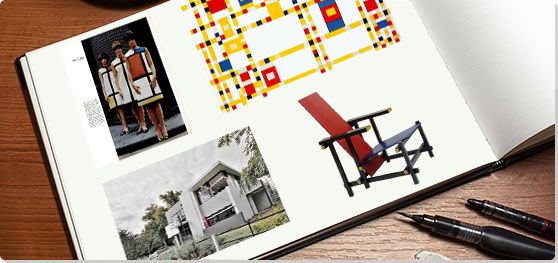

Fashion designers have also felt the influence of Neo-Plasticism. Lola Prusac created Hermes bags with Neo-Plastic designs in the 1930s. The fashion designer, Yves Saint Laurent debuted his very successful, "Mondrian Collection," in 1965 and declared, "The masterpiece of the 20th century is a Mondrian." Even into the 21st century, Nike produced a tennis shoes with Neo-Plastic designs in 2008, and more recently, Alexander McQueen couture house's collections reflected the influence of the movement, as seen in its 2014 ballet flats. Given Mondrian's concern that Neo-Plasticism not become a mere technique or take on a decorative purpose, the abundance of contemporary merchandise from coffee cups to refrigerator magnets featuring Neo-Plastic design is an ironic testimony to the continuing influence of the movement.

Useful Resources on Neo-Plasticism

- Piet Mondrian: Life and WorkOur PickBy Cees W. de Jong, Marty Bax, Marjory Degen, et al.

- Bart Van Der LeckBy Toos Van Kooten

- Gerrit RietveldBy Ida van Zijl

- On European Architecture: Complete Essays from Het Bouwbedrijf, 1924-1931By Theo Van Doesburg

- The New Art--the New Life: The Collected Writings Of Piet Mondrian (Documents of Twentieth-Century Art)By Harry Holtzman and Martin S. James

- Mondrian: The Art of DestructionBy Carel Blotkamp

- MondrianOur PickBy John Milner

- Mondrian 1892-1914: The Path to AbstractionBy Hans Janssen and Joop M. Joosten

- Theo Van Doesburg: A New Expression of Life, Art, and Technology Hardcover - August 9, 2016By Gladys Fabre

- Theo Van Doesburg: Painting into Architecture, Theory into Practice (Cambridge Urban and Architectural Studies) 1st EditionBy Allan Doig