Summary of Performance Art

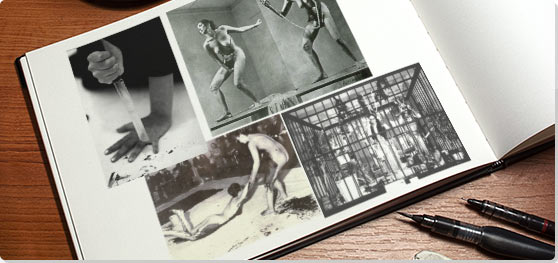

Performance is a genre in which art is presented "live," usually by the artist but sometimes with collaborators or performers. It has had a role in avant-garde art throughout the 20th century, playing an important part in anarchic movements such as Futurism and Dada. Indeed, whenever artists have become discontented with conventional forms of art, such as painting and traditional modes of sculpture, they have often turned to performance as a means to rejuvenate their work. The most significant flourishing of performance art took place following the decline of modernism and Abstract Expressionism in the 1960s, and it found exponents across the world. Performance art of this period was particularly focused on the body, and is often referred to as Body art. This reflects the period's so-called "dematerialization of the art object," and the flight from traditional media. It also reflects the political ferment of the time: the rise of feminism, which encouraged thought about the division between the personal and political and anti-war activism, which supplied models for politicized art "actions." Although the concerns of performance artists have changed since the 1960s, the genre has remained a constant presence, and has largely been welcomed into the conventional museums and galleries from which it was once excluded.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The foremost purpose of performance art has almost always been to challenge the conventions of traditional forms of visual art such as painting and sculpture. When these modes no longer seem to answer artists' needs - when they seem too conservative, or too enmeshed in the traditional art world and too distant from ordinary people - artists have often turned to performance in order to find new audiences and test new ideas.

- Performance art borrows styles and ideas from other forms of art, or sometimes from other forms of activity not associated with art, like ritual, or work-like tasks. If cabaret and vaudeville inspired aspects of Dada performance, this reflects Dada's desire to embrace popular art forms and mass cultural modes of address. More recently, performance artists have borrowed from dance, and even sport.

- Some varieties of performance from the post-war period are commonly described as "actions." German artists like Joseph Beuys preferred this term because it distinguished art performance from the more conventional kinds of entertainment found in theatre. But the term also reflects a strain of American performance art that could be said to have emerged out of a reinterpretation of "action painting," in which the object of art is no longer paint on canvas, but something else - often the artist's own body.

- The focus on the body in so much Performance art of the 1960s has sometimes been seen as a consequence of the abandonment of conventional mediums. Some saw this as a liberation, part of the period's expansion of materials and media. Others wondered if it reflected a more fundamental crisis in the institution of art itself, a sign that art was exhausting its resources.

- The performance art of the 1960s can be seen as just one of the many disparate trends that developed in the wake of Minimalism. Seen in this way, it is an aspect of Post-Minimalism, and it could be seen to share qualities of Process art, another tendency central to that umbrella style. If Process art focused attention on the techniques and materials of art production. Process art was also often intrigued by the possibilities of mundane and repetitive actions; similarly, many performance artists were attracted to task-based activities that were very foreign to the highly choreographed and ritualized performances in traditional theatre or dance.

Overview of Performance Art

Yoko Ono said, “I thought art was a verb, rather than a noun,” and embodied the concept in her Cut Piece (1964) – pioneering Performance Art – where, holding a pair of scissors and kneeling on stage, she invited the audience to cut away pieces of her clothing.

Artworks and Artists of Performance Art

The Anthropometries of the Blue Period

Although painting sat at the center of Yves Klein's practice, his approach to it was highly unconventional, and some critics have seen him as the paradigmatic neo-avant-garde artist of the post-war years. He initially became famous for monochromes - in particular for monochromes made with an intense shade of blue that Klein eventually patented. But he was also interested in Conceptual art and performance. For the Anthropometries, he painted actresses in blue paint and had them slather about on the floor to create body-shaped forms. In some cases, Klein made finished paintings from these actions; at other times he simply performed the stunt in front of finely dressed gallery audiences, and often with the accompaniment of chamber music. By removing all barriers between the human and the painting, Klein said, "[the models] became living brushes...at my direction the flesh itself applied the color to the surface and with perfect exactness." It has been suggested that the pictures were inspired by marks left on the ground in Hiroshima and Nagasaki following the atomic explosions in 1945.

Performed at Robert Godet's, Paris 1958 and at Galerie Internationale d'Art Contemporain, Paris 1960

Cut Piece

Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece, first performed in 1964, was a direct invitation to an audience to participate in an unveiling of the female body much as artists had been doing throughout history. By creating this piece as a live experience, Ono hoped to erase the neutrality and anonymity typically associated with society’s objectification of women in art. For the work, Ono sat silent upon a stage as viewers walked up to her and cut away her clothing with a pair of scissors. This forced people to take responsibility for their voyeurism and to reflect upon how even passive witnessing could potentially harm the subject of perception. It was not only a strong feminist statement about the dangers of objectification, but became an opportunity for both artist and audience members to fill roles as both creator and artwork.

Performed at Yamaichi Concert Hall, Kyoto, Japan 1964

Shoot

In many of his early 1970s performance pieces, Burden put himself in danger, thus placing the viewer in a difficult position, caught between a humanitarian instinct to intervene and the taboo against touching and interacting with art pieces. To perform Shoot, Burden stood in front of a wall while one friend shot him in the arm with a .22 long rifle, and another friend documented the event with a camera. It was performed in front of a small, private audience. One of Burden's most notorious and violent performances, it touches on the idea of martyrdom, and the notion that the artist may play a role in society as a kind of scapegoat. It might also speak to issues of gun control and, in the context of the period, the Vietnam War.

Performed at F Space, Santa Ana, California

Seedbed

In Seedbed, 1972 Vito Acconci laid underneath a custom made ramp that extended from two feet up one wall of the Sonnabend Gallery and sloped down to the middle of the floor. For eight hours a day during the course of the exhibition, Acconci laid underneath the ramp masturbating as guest’s walked above his hidden niche. As he performed this illicit act he would utter fantasies and obscenities toward the gallery guests into a microphone, which became audibly piped out through the room for all to hear.

The piece placed Acconci in a position that was both public and private. It also created a provocative intimacy between artist and audience that produced multiple levels of feeling. Participants were prone to shock, discomfort, or perhaps even arousal. By positioning himself in two roles, both as giver and receiver of pleasure, Acconci furthered body art’s dictum of artist and artwork merging as one. He also used his sperm as a medium within the piece.

Performed at Sonnabend Gallery in New York City 1972

Rhythm 10

In Rhythm 10, Abramović uses a series of 20 knives to quickly stab at the spaces between her outstretched fingers. Every time she pierces her skin, she selects another knife from those carefully laid out in front of her. Halfway through, she begins playing a recording of the first half of the hour-long performance, using the rhythmic beat of the knives striking the floor, and her hand, to repeat the same movements, cutting herself at the same time. This piece exemplifies Abramović's use of ritual in her work, and demonstrates what the artist describes as the synchronicity between the mistakes of the past and those of the present.

Performed at a festival in Edinburgh

Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me

For three consecutive days in May, 1974, Beuys enclosed himself in a gallery with a wild coyote. Having previously announced that he would not enter the United States while the Vietnam War proceeded, this piece was his first and only action in America, and Beuys was ferried between the airport and the gallery in an ambulance to ensure that his feet did not have to touch American soil. Coyote centered on ideas of America wild and tamed. In an attempt to connect with an idea of wild, pre-colonial America, Beuys lived with a coyote for several days, attempting to communicate with it. He organized a sequence of interactions that would repeat for the duration of the piece, such as cloaking himself in felt and using a cane as a "lightening rod," and following the coyote around the room, bent at the waist and keeping the cane pointed at the coyote. Copies of The Wall Street Journal arrived daily, and were used as a toilet by the coyote, as if to say, "everything that claims to be a part of America is part of my territory."

Performed at Rene Block Gallery, New York NY

Interior Scroll

Carolee Schneemann, who defines herself as a multi-disciplinary artist, working across a variety of media, first made an impact in the context of feminist art. Interior Scroll is one of her most famous works. To stage it, she smeared her nude body with paint, mounted a table, and began adopting some of the typical poses that models strike for artists in life class. Then she proceeded to extract a long coil of paper from her vagina, and began to read the text written on it. It was once thought that the text derived from her response to a male filmmaker's critique of her films (some of her most notable films of the time included imagery of the Vietnam War, and documentation of a performance entitled Meat Joy, involving nude bodies writhing about in meat). The filmmaker had apparently commented on her penchant for "personal clutter...persistence of feelings...[and] primitive techniques" - in effect, qualities that were deemed "feminine." But Schneemann has since said that the text came from a letter sent to a female art critic who found her films hard to watch. By using her physical body as both a site of performance and as the source for a text, Schneemann refused the fetishization of the genitals.

Performed in East Hampton, NY and at the Telluride Film Festival, Colorado

Art/Life: One Year Performance (a.k.a. Rope Piece)

For the length of this year long endurance piece, Montano and Hsieh were bound to each other by an 8-foot piece of rope. They existed in the same space, but never touched. In Hsieh's original idea, the rope represented the struggle of humans with one another and their problems with social and physical connection. As the work evolved, the rope took on more meanings. It controlled, yet expanded the patterns of both of the artists' lives, becoming a visual symbol of the relationship between two people. The 365-day length of the work was critical, as it heightened the piece from performance to life. Life and art could not be separated within a work where living was the art. Hsieh explained that if the piece was only one or two weeks, it would be more like a performance, but a year, "has real experience of time and life."

Performed in New York City

Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit Buenos Aires

Dressed in ridiculous costume, engaged in stereotypical "native" tasks and enclosed in a cage, Fusco and Gomez-Pena addressed the practice of human displays, and fetishization of the "other." Fusco wore several different looks, including hair braids, a grass skirt and a leopard skin bra, while Gomez-Pena sported an Aztec style breastplate. The two ate bananas, performed "native dances" and other "traditional rituals" and were led to the bathroom by museum guards on leashes. The piece was first performed at Columbus Plaza, Madrid, Spain, as a part of the Edge '92 Biennial, which was organized in commemoration of Columbus's voyage to the New World. It was intended as a satirical comedy, yet half of the viewers thought that the fictitious Amerindian specimens were real.

Performed at Columbus Plaza, Madrid, Spain, and performed in various international venues until 1994

Beginnings of Performance Art

Early Avant-Gardes Utilize Performance

20th century performance art has its roots in early avant-gardes such as Futurism, Dada and Surrealism. Before the Italian Futurists ever exhibited any paintings they held a series of evening performances during which they read their manifestoes. And, similarly, the Dada movement was ushered into existence by a series of events at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. These movements often orchestrated events in theatres that borrowed from the styles and conventions of vaudeville and political rallies. However, they generally did so in order to address themes that were current in the sphere of visual art; for instance, the very humorous performances of the Dada group served to express their distaste for rationalism, a current of thought that had recently surged from the Cubism movement.

Post-war Performance Art

The origins of the post-war performance art movement can be traced to several places. The presence of composer John Cage and dancer Merce Cunningham at North Carolina's Black Mountain College did much to foster performance at this most unconventional art institution. It also inspired Robert Rauschenberg, who would become heavily involved with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Cage's teaching in New York also shaped the work of artists such as George Brecht, Yoko Ono, and Allan Kaprow, who formed part of the impetus behind the Fluxus movement and the birth of "happenings," both of which placed performance at the heart of their activities.

In the late 1950s, performance art in Europe began to develop alongside the work being done in the United States. Still affected by the fallout from World War II, many European artists were frustrated by the apolitical nature of Abstract Expressionism, the prevalent movement of the time. They looked for new styles of art that were bold and challenging. Fluxus provided one important focus for Performance art in Europe, attracting artists such as Joseph Beuys. In the next few years, major European cities such as Amsterdam, Cologne, Düsseldorf, and Paris were the sites of ambitious performance gatherings.

Actionism, Gutai, Art Corporel, and Auto-Destructive Art

Other manifestations included the work of collectives bound together by similar philosophes like the Viennese Actionists, who characterized the movement as "not only a form of art, but above all an existential attitude." The Actionists' work borrowed some ideas from American action painting, but transformed them into a highly ritualistic theatre that sought to challenge the perceived historical amnesia and return to normalcy in a country that had so recently been an ally of Adolph Hitler. The Actionists also protested governmental surveillance and restrictions of movement and speech, and their extreme performances led to their arrest several times.

In France, art corporel, or body art, compiled an avant-garde set of practices that brought body language to the center of artistic practice.

In Japan, the Gutai became the first post-war artistic group to reject traditional art styles and adopt performative immediacy as a rule. They staged large-scale multimedia environments and theatrical productions that focused on the relationship between body and matter.

In Britain, artists such as Gustav Metzger pioneered an approach described as "Auto-Destructive art," in which objects were violently destroyed in public performances that reflected on the Cold War and the threat of nuclear destruction.

The Emergence of Feminist and Performance Art in the U.S.

American Performance art in the 1960s and 1970s coincided with the rise of second-wave feminism. Women artists turned to performance as a confrontational new medium that encouraged the release of frustrations at social injustice and the ownership of discussion about women's sexuality. This permitted rage, lust, and self-expression in art by women, allowing them to speak and be heard as never before. Women performers seized an opportune moment to build performance art for themselves, rather than breaking into other already established, male-dominated forms. They frequently dealt with issues that had not yet been undertaken by their male counterparts, bringing fresh perspectives to art. For example, Hannah Wilke criticized Christianity's traditional suppression of women in Super-t-art (1974), where she represented herself as a female Christ. During and since the beginning of the movement, women have made up a large percentage of performance artists.

The Vietnam War also provided significant material for performance artists during this era. Artists such as Chris Burden and Joseph Beuys, both of whom made work in the early 1970s, rejected US imperialism and questioned political motivations. Performance art also developed a major presence in Latin America, where it played a role in the Neoconcretist movement.

Performance Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Instead of seeking entertainment, the audience for performance art often expects to be challenged and provoked. Viewers may be asked to question their own definitions of art, and not always in a comfortable or pleasant manner. As regards style, many performance artists do not easily fall into any identified stylistic category, and many more still refuse their work to be categorized into any specific sub-style. The movement produced a variety of common and overlapping approaches, which might be identified as actions, Body art, happenings, Endurance art, and ritual. Although all these can be described and generalized, their definitions, like the constituents of performance art as a movement, are continuously evolving. And some artists have made work that falls into different categories. Yves Klein, for instance, staged some performances that relate to the Fluxus movement, and have qualities of rituals and happenings, yet his Anthropometries (1958) also relate to Body art.

Action

The term "action" constitutes one of the earliest styles within modern performance art. In part, it serves to distinguish the performance from traditional forms of entertainment, but it also highlights an aspect of the way performers viewed their activities. Some saw their performances as related to the kind of dramatic encounter between painter and painting that critic Harold Rosenberg talked of in his essay 'The American Action Painters' (1952). Others liked the word action for its open-endedness, its suggestion than any kind of activity could constitute a performance. For example, early conceptual actions by Yoko Ono consisted of a set of proposals that the participant could undertake, such as, "draw an imaginary map...go walking on an actual street according to the map..."

Body Art diffused the veil between artist and artwork by placing the body front and center as actor, medium, performance, and canvas amplifying the idea of authentic first person perspective. In the post-1960's atmosphere of changing social mores and thawed attitudes toward nudity, the body became a perfect tool to make the political personal. Feminist art burgeoned in this realm as artists such as Carolee Schneemann, VALIE EXPORT, and Hannah Wilke turned their bodies into tools for bashing the disconnect between historical portrayals of the female experience and a newly empowered reality. Some artists like Ana Mendieta and Rebecca Horn questioned the body’s relationship to the world at large, including its limitations. Other artists, like Marina Abramović, Chris Burden and Gina Pane, performed shocking acts of violence toward their own bodies, which provoked audiences to question their own participation, in all its permutations, as voyeurs.

Happenings

Happenings were a popular mode of performance that arose in the 1960s, and which took place in all kinds of unconventional venues. Heavily influenced by Dada, they required a more active participation from viewers/spectators, and were often characterized by an improvisational attitude. While certain aspects of the performance were generally planned, the transitory and improvisational nature of the event attempted to stimulate a critical consciousness in the viewer and to challenge the notion that art must reside in a static object.

Endurance

A number of prominent performance artists have made endurance an important part of their practice. They may involve themselves in rituals that border on torture or abuse, yet the purpose is less to test what the artist can survive than to explore such issues as human tenacity, determination, and patience. Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh has been one important exponent of this approach; Marina Abramović offers other examples. Allan Kaprow was perhaps the most influential figure in the happenings movement, though others who were involved include Claes Oldenburg, who would later be associated with Pop art.

Ritual

Ritual has often been an important part of some performance artists' work. For example, Marina Abramović has used ritual in much of her work, making her performances seem quasi-religious. This demonstrates that while some aspects of the performance art movement have been aimed at demystifying art, bringing it closer to the realms of everyday life, some elements in the movement have sought to use it as a vehicle for re-mystifying art, returning to it some sense of the sacred that art has lost in modern times.

Later Developments - After Performance Art

After the success performance art experienced in the 1970s, it seemed that this new and exciting movement would continue in popularity. However, the market boom of the 1980s, and the return of painting, represented a significant challenge. Galleries and collectors now wanted something material that could be physically bought and sold. As a result, performance fell from favor, but it did not disappear entirely. Indeed, the American performer Laurie Anderson rose to considerable prominence in this period with dramatic stage shows that engaged new media and directly addressed the period's changing issues.

Women performance artists were particularly unwilling to give up their newfound forms of expression, and continued to be prolific. In 1980, there was enough material to produce the exhibition A Decade of Women's Performance Art, at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. Organized by Mary Jane Jacob, Moira Roth, and Lucy R. Lippard, the exhibition was a broad survey of works done in the United States during the 1970s, and included documentations of performances in photographs and texts.

And in Eastern Europe throughout the 1980s, performance art was frequently used to express social dissent.

Moving into the 1990s, Western countries began to embrace multiculturalism, helping to propel Latin American performance artists to new fame. Guillermo Gomez-Pena and Tania Bruguera were two such artists who took advantage of the new possibilities afforded by large biennials with international reach, and they presented work about oppression, poverty, and immigration in Cuba and Mexico. In 1991 and 1992, Next Wave festivals at the Brooklyn Academy of Music reflected these trends with works from the American-Indian group Spider Woman Theater, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, and Urban Bush Women dance company.

Performance art is a movement that thrives in moments of social strife and political unrest. At the beginning of the 1990s, performance art once again grew in popularity, this time fueled by new artists and audiences; issues of race, immigration, queer identities, and the AIDS crisis began to be addressed. However, this work often caused controversy, indeed it came to be at the center of the so-called Culture Wars of the 1990s, when artists Karen Finley, Tim Miller, John Fleck and Holly Hughes passed a peer review board to receive funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, only to have it withdrawn by the NEA on the basis of its content, which related to sexuality.

Today's performance artists continue to employ a wide variety of mediums and styles, from installation to painting and sculpture. British artist Tris Vonna-Michell mixes narrative, performance and installation. Tino Sehgal blends ideas borrowed from dance and politics in performances that sometimes take the form of conversations engaged in by the audience themselves; no conventional staged performance takes place, and no documentation remains of the events. Sehgal's solo exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2010 is a sign of how close the genre has now come to being accepted by mainstream art institutions.

Useful Resources on Performance Art

- Performance Art: From Futurism to PresentOur PickBy Roselee Goldberg

- Performance: Live Art Since the '60sOur PickBy Roselee Goldberg, Laurie Anderson

- Body Art/Performing the SubjectBy Amelia Jones

- The Amazing Decade: Women and Performance Art in America, 1970-1980By Moira Roth

- Corpus Delecti: Performance Art of the AmericasBy Coco Fusco

- Performance Art in ChinaBy Thomas Berghuis

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI