Summary of Vanessa Bell

Vanessa Bell defied the Victorian strictures of her upbringing to forge a life filled with creativity, collaboration, and sexual liberation. A vital founder of the Bloomsbury Group, Bell, along with her novelist sister Virginia Woolf, the critic Roger Fry, and the artist Duncan Grant among others, embraced the avant-garde styles of continental Europe to advance modern art and to break down the barriers between fine and applied arts. Bucking traditional English mores, Bell created a distinctly modern oeuvre that ranged over still lifes, landscapes, interiors, and abstract paintings as well as decorative arts such as textiles, pottery, and furniture. While Bell embraced Fauvist and Cubist styles, making her paintings some of the most radical Britain had yet seen, her insistence on drawing inspiration from her domestic life led later historians and critics to downplay her importance in the development of modern art, an assessment that is now rapidly changing.

Accomplishments

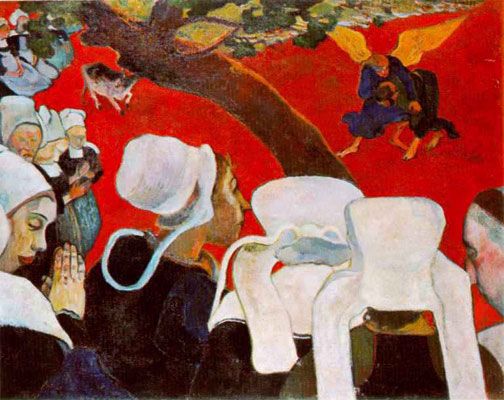

- Bell synthesized the techniques and explorations of the Post-Impressionist painters, such as Cézanne, Matisse, and Gauguin, to create modern compositions with bold forms and colors. She simplified human figures to their constituent shapes, flattened pictorial space, and used saturated colors to create patterns of objects and shapes, creating paintings that were some of the most radical in Britain at the time.

- The close group of family and friends that Bell cultivated and the untraditional domestic sphere she fostered provided inspiration and subject matter throughout her painting career. In this space abstract textiles, hand fashioned pottery, abstract paintings, and portraits of her loved ones mingled to create a new, strikingly modern way of living.

- While innovative in the development of abstract painting, Bell wandered among various types of subject matter and blurred the boundaries between fine and decorative arts. While perhaps not a strict modernist, her attitude spoke to an anti-authoritarian stance that defied the constraints and limitations of what was expected of a modern painter.

Important Art by Vanessa Bell

Landscape with Haystack, Asheham

While Bell pays homage to Monet in her choice of subject matter - a large haystack dominates the landscape - she emulates Cézanne in her compositional structure and paint handling. Instead of Monet's light-dappled haystack, Bell uses muted browns and greens in flat swaths to construct the sculptural pile of hay and the rest of the landscape. The visible strokes of the grey sky as well as the patch of grass in the near foreground have much in common with Cézanne's method of painting. Having spent time in Paris as well as seeing Roger Fry's groundbreaking Post-Impressionist show in 1910, Bell synthesized the Post-Impressionist style to create a unique, modern approach to landscape painting that didn't exist in England.

The setting, Asheham, was where her sister Virginia Woolf and her brother-in-law Leonard Woolf found a country house shortly after they married in 1912. Bell painted the house in the background, reinforcing her personal connection to the landscape. While Bell renders a real place, her focus is on the structural design of the painting, how patches of color fit together to create a strong image, and echoes Fry's formal assessments that design was an essential aspect of modern painting.

Oil on board - Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts

Studland Beach

In Studland Beach two women sit on the sand with their backs to the viewer, looking out towards the water. At the water's edge a woman in a blue dress stands in front of a white tent, while four figures, perhaps children, sit near her feet. As she often did when selecting her subjects, Bell drew on experiences from her life. The setting for this work, a beach in Dorset, England, was a favored vacationing spot for Bell and her family around the time she painted this canvas.

Bell's mastery of composition is evident in this painting. She employs a modern approach to color and form, similar to Gauguin's and Matisse's. Most notably, the bold placement of the white vertical structure of the tent stands in stark comparison to the diagonal between the deep blue water and the warm tones of the beach, and her simplification of form gives the figures an enduring weight.

This is one of many paintings Bell created that featured women as the subject. While the women in the foreground seem to be sharing quiet conversation, Bell imbues the overall scene with loneliness and isolation , perhaps a commentary on her own socially reserved personality. Sometimes her portraits featured women with obscured faces, but here we see no faces at all. Additionally, the tent functions as a changing room for women to don their bathing suits, further separating them from the other beach-goers.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Maud

Named after the London socialite, Lady Maud Cunard, the textile design Maud features large swatches of blue, green, and orange passages broken up by thin, dark brown lines. The pale linen, left partially exposed, brings a lightness to the composition. The repeating pattern would have been stenciled on large pieces of fabric, and in fact, Bell used Maud for curtains in her Gordon Square home.

Designed for the Omega Workshops, which she co-founded with Roger Fry and Duncan Grant, Bell's decorative work relied on the Post-Impressionist aesthetics favored by the Bloomsbury Group. As professor and historian Claudia Tobin notes, "[T]he Omega sought to revolutionize the aesthetics and ultimately the values of the English interior with an approach to design informed by the new chromatic and formal freedoms of post-impressionism." Breaking down the distinctions between applied art and painting was one of the Omega's goals, and in fact, Bell at this time started pursuing purely abstract paintings. Christopher Reed acknowledged the cross-fertilization, stating, "[I]t was the abstract patterning of the Omega textiles that made non-representational painting possible for the Bloomsbury artists. Stylistically, they have much in common: the Omega technique of marking up a design on squared paper carries through to the angular, geometric composition of the easel paintings." Bell's work tracked the work of other European female avant-gardes such as Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Hannah Höch, and Sonia Delaunay-Terk, who were also experimenting with abstraction in both textiles and the fine arts.

Painted linen - Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Abstract Painting

Various sized rectangles of burgundy, green, orange, pink, and blues hover above a rich mustard-colored field. The longer rectangles congregate toward the left side of the painting while the orange and pink ones float in more isolated fashion. While the relationships between the shapes and their connection with the field call attention to the flatness of the picture plane, they also create an evocative sense of depth. Additionally, the texture of the painting is sumptuous, and has much in common with her textile designs.

Between 1914 and 1915, Bell, painting alongside Roger Fry and Duncan Grant, took the plunge into purely abstract painting. While her textile designs were certainly a catalyst, for several years she had been simplifying the human form and flattening the foregrounds and backgrounds of her painting, thus charting a path toward abstraction. While she only briefly experimented in this style, in doing so she demonstrated her ability to push the boundaries of what was traditionally considered acceptable in art and was on the forefront of European abstraction.

Art historian Grace Brockington suggests that while this painting is abstract it can also be read metaphorically as an embodiment of the Bloomsbury Group. She writes that the Bloomsbury artists "rejected prescriptive structures of thought and social organization: grand theories, consistent styles, artistic groups with memberships and manifestos. Instead, they cultivated the loose, informal, improvised model of the conversation, which tolerates and indeed depends on difference, and assumes a more or less equal relationship between the participants." After this brief experiment with abstraction, Bell returned to figural works to achieve her artistic goals. While form was always of the utmost importance in her compositions, she conceded that "certain qualities in life, what I call movement, mass, weight, have aesthetic value."

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Oranges and Lemons

A large yellow vase dominates the center of the canvas, and an explosion of green leaves, lemons, and oranges spill out of it. The entire arrangement is set before a boldly colored, abstract wall paper, which adds to the dynamism and exuberance of the subject.

Floral still life arrangements were a popular theme for Bell throughout her career, and she consistently painted them in a modern style that tended toward flatness and used vibrant colors. The influence of Post-Impressionism is clearly on view, and yet Bell succeeds in making works that are distinctly her own. Specifically, according to Regina Marler, "[T]he black outlines of vase and fruit are...Cézannesque. In Bell's slashing, incomplete strokes and energetic handling one can clearly see the influence of so-called primitive art such as tribal sculpture..., as well as that of Picasso and Matisse, but the painting has a swagger that shakes off artistic debt."

Additionally, the painting is a testament to how Bell's personal relationships heavily influenced her art. The bouquet depicted came from her lover Duncan Grant, who sent the fruits as a gift to Bell. She described the importance of this gift in a letter to Grant written in 1914. While thanking him, she also made clear her attempt to create her own artistic style, stating, "They were so lovely that against all modern theories I stuck some into my yellow Italian pot and at once began to paint them. I mean one isn't supposed nowadays to paint what one thinks beautiful. But the color was so exciting that I couldn't resist it."

Oil on cardboard - Private Collection

Self-portrait

In this self-portrait, Vanessa Bell dominates the canvas. Pictured seated from the waist up, she wears a white dress with a gray gingham pattern, lined with a plunging pink collar. Her body turns towards the left so that she faces out, looking to some point off the right-side of the canvas. Her brown hair is pulled tightly back from her face and matches the sternness of her expression. Behind her is an abstract wash of green, purple, and yellow stripes with a small patch of blue at the top left of the canvas. While at this time she shifted away from pure abstraction, we can see echoes of abstraction in the background of this painting, which firmly secures her role as a modernist portrait painter.

This work is an important early example of the many self-portraits Bell created throughout her career. While portraits were an important part of her oeuvre, and she made many of family and friends, her self-portraits offer a rare glimpse into her personality. While she had an active social life among those in her inner circle, she was often reserved and avoided the social spotlight. Here she presents a strong, serious, and stable image that is manifested not only in her expression but in the exaggerated physical heft of her (in reality) slight frame. Having been forced to attend social gatherings by her step-brother, Bell wanted to now define her life on her own terms and so set about creating a world of her own making. Curator Sarah Milroy writes how her self-portrait "affirms her continued tendency to define herself by her starch rather than her flounces. Here she presents herself in an attitude of snoutish defiance, her shoulders braced at a combative angle. This is how she would have the world see her."

Oil on canvas - Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut

View into the Garden

Part still life, part landscape, Bell's painting depicts a partial interior of a room that includes a chair on which rests a book and a table with a vase filled with wild flowers. In the center and right side of the canvas is an open doorway through which can be seen a wicker chair placed in front of a lush green garden.

This is one of the many paintings Bell created that used her home, Charleston, as the setting. Choosing to spend the majority of her life there, leaving only periodically to travel or for brief stays in London, Charleston offered her great comfort and a place to share with her family and friends. Some of her most inspiring and important paintings revolve around the subject of her home.

Unlike other modern artists of the time, Bell did not try to distance herself from domestic life, rather she embraced domesticity in her work, first in her Omega Workshops interior designs and later in the themes of her paintings. Unlike other early modernists who made concerted efforts to avoid such themes, for the Bloomsbury Group, modernism was intricately linked to domesticity. According to Christopher Reed, "Bell's art testifies to her belief in the home as the crucible in which artists effect the transformation of the personal into the abstract - the more generalized emotions associated with form - that was for Bloomsbury the hallmark of modernism."

Oil on board - Bolton Library and Museum Services, Greater Manchester, England

Biography of Vanessa Bell

Childhood and Education

The complicated family dynamic into which Vanessa Stephen was born would foreshadow the complex relationships she would have throughout her life. The eldest child born to author Sir Leslie Stephen and Julia Duckworth, her three siblings included one sister who would become the famed author Virginia Woolf. She also had a half-sister (her mother's from her first marriage) and two half-brothers (her father's sons), who Bell accused many years later of molesting her.

Early Training

While her father could be a demanding and controlling figure, he encouraged his children's academic and creative pursuits. Showing an interest in art at an early age, Bell received lessons at home before enrolling in an art school run by Arthur Cope in 1896 and later the prestigious Royal Academy in 1901, where she studied painting with John Singer Sargent, who interestingly, disliked her heavy use of gray. It was also during this time, through her brother Thoby, that she met her future husband Clive Bell in 1902.

Tragedy and loss impacted the progression of Bell's artistic training. After her mother's death in 1895 and her half-sister's death two years later, her father looked to her to care for him, her siblings, and to run the household, forcing her to limit the time she could devote to her studies. She was sarcastically nicknamed "the Saint" by her sister Virginia, establishing a slight antagonism between the two that would continue throughout their close relationship. Later when her father developed cancer, she was forced to reduce her time at the Royal Academy even further.

Her father's death in February 1904 brought physical and mental liberation for Bell, who while not permitted to reenroll in the Royal Academy, began to travel in Europe to study art. She and her siblings also moved from the family home to a house in the fashionable London neighborhood of Bloomsbury. Of this newfound freedom Bell stated, "It was exhilarating to have left the house in which had been so much gloom and depression, to have come to these white walls, large windows opening on to trees and lawns, to have one's own room, be master of one's own time." It was here that family and intellectual and artistic friends, including Clive Bell, began a series of Thursday evening gatherings that fueled her creative pursuits and formed the foundation for what would be termed the "Bloomsbury Group."

At this time, Bell's work was first exhibited, and she helped form the Friday Club in 1905, with the goal of supporting public exhibitions of the group's work. Her forthrightness and aggressive promotion of the club helped to establish her lifelong reputation for defying social conventions and mores of the period. Her refusal to tie herself down in a marriage led her to resist Clive Bell's first two marriage proposals before accepting and marrying him in 1907, shortly after the death of her brother Thoby.

Mature Period

Although she took her husband's name, Vanessa Bell's marriage was far from conventional. Both she and her husband had multiple lovers throughout their union. Her first included a longtime relationship with critic Roger Fry, whose show on Post-Impressionism (and coining of the term itself) helped to shape the direction of her work, and the second was a relationship with homosexual artist Duncan Grant. Grant would live with her for more than forty years, often alongside some of his male lovers, which included Bell's brother Adrian. The always witty American Dorothy Parker remarked that the group that "lived in squares, painted in circles, and loved in triangles." Bell would have two sons, Julian and Quentin, with Clive Bell, and she would later have a daughter Angelica with Grant whom Clive, to avoid scandal, claimed as his own. Angelica was not told Grant was her father until she was seventeen years old.

Unlike many female artists of the period, Bell was able to balance the demands of motherhood (which she liked) with that of her career and continued to be active as a professional artist throughout her life. Along with Fry and Grant, Bell founded the Omega Workshops in 1913. The group attempted to produce commercial products while focusing on paintings, ceramics, fabrics, furniture, and stained-glass designs that built on the Post-Impressionist style. They also hosted exhibitions of participating artists' work. Bell experimented with complete abstraction in 1914 and into 1915, but largely her work always contained a figurative element. While a vehicle to highlight Bell's art, Omega also demonstrated how her work was often intricately fueled by the support of like-minded artists.

Bell's art thrived when she and her unconventional family relocated in 1916 to the Sussex countryside to a farmhouse called Charleston. The move was precipitated by the need for Grant, along with his partner David "Bunny" Garnett, to find employment to avoid prison as conscientious observers during World War I. She and Clive Bell never formally divorced or separated, and he would often visit Charleston for long stretches of time. In another example of her complicated personal relationships, Bunny would years later marry Bell and Grant's daughter despite a more than twenty-year age difference and his having once been in love with her father.

Charleston became a canvas for her art as Bell made many design changes to the home including painting works on walls and furniture and artistically designing the gardens. It was here that she, often working alongside Grant, would paint the subjects for which she was best known: landscapes, portraits, and still lifes.

After the war, Bell traveled often and her paintings were influenced by the places she visited and the people she met. She attended the salons at Gertrude Stein's Paris home and visited the studios of Matisse and Picasso. While her own profile as an artist grew, her reputation was always overshadowed by Grant's. While she generally appeared fine with the arrangement and herself played an active role in trying to elevate Grant's work, she did once strongly object to a journalist describing her as "Mrs. Duncan Grant."

Late Period

While artistically productive, the last decades of Bell's career were filled with many tragedies, which began with Roger Fry's death in 1934. She subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown, and after her eldest son Julian, to whom she was extremely close, died in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, she took a long time to recover. Four years later in 1941 her sister, Virginia Woolf, committed suicide.

Despite the deep losses, her art provided an outlet and a refuge for Bell. She received an important commission to decorate the RMS Queen Mary ship in 1936. The original design was found inappropriate for the Catholic chapel room, and to appease all parties, Bell was assigned a new room, which was to be used for private dining. Also, in 1939 she was commissioned along with Grant and her son and daughter, to create a painting for Berwick Church in Sussex, a surprising commission since Bell had long been vocal in her distrust of and lack of interest in religion.

In the last years of her life, the somewhat socially reserved Bell (except with those in her own circle of acquaintances), withdrew further from society. She stayed mainly at Charleston spending time with Grant, her children, and grandchildren; and her home continued to provide inspiration for her work.

In April 1961, Bell developed bronchitis from which she would not recover. She died shortly after of heart failure and was buried in the cemetery near Charleston.

The Legacy of Vanessa Bell

In her unique approach to modernism, Vanessa Bell was in many ways a trailblazer. She was one of the first women in England to experiment with abstraction and her vision was behind the forming of leading early-20th-century art groups and programs.

The legacy of her work continues to inspire artists in multiple fields. Comparisons have been made between her composition and color use and the style of contemporary artist David Hockney. Recently, musician Patti Smith created a set of photographs from a visit to Charleston, incorporating Bell's designs. In addition, the Burberry fashion house created a line of bags inspired by Bell's textiles and paintings.

Influences and Connections

-

![Roger Fry]() Roger Fry

Roger Fry -

![Duncan Grant]() Duncan Grant

Duncan Grant -

![Gertrude Stein]() Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein ![Clive Bell]() Clive Bell

Clive Bell![Virginia Woolf]() Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

-

![David Hockney]() David Hockney

David Hockney ![Walter Sickert]() Walter Sickert

Walter Sickert- Frederick Etchells

- Jessie Etchells

- Nina Hamnett

-

![Roger Fry]() Roger Fry

Roger Fry -

![Gertrude Stein]() Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein ![Clive Bell]() Clive Bell

Clive Bell![Virginia Woolf]() Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf- Lytton Strachey