Summary of Jacques-Louis David

The quintessential Neoclassical painter, David's monumental canvases were perhaps the final triumph of traditional history painting. Adopting the fashionable Greco-Roman style, David blended these antique subjects with Enlightenment philosophy to create moral exemplars. His linear forms dramatically illustrated narratives that often mirrored contemporary politics. As the premier painter of his day, David served the monarchy of Louis XVI, the post-revolutionary government, and the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, despite the radical differences in these ruling regimes. He also ran an important studio where his students would later rebel against his example, sowing the seeds of modernism.

Accomplishments

- David was the first French artist to unite classical subjects with a linear precision and minimalist composition. Completely rejecting the decorative and painterly effects of the Rococo, his canvases created powerful, didactic works of moral clarity with few distractions or pictorial flourishes. David's paintings answered the demand for art that directly conveyed civic virtues to a wide audience.

- Although paintings such as The Oath of the Horatii and Death of Socrates would come to be associated with the Revolution of 1789, David's earliest successes were iconic images of valor and noble deeds, commissioned by royal and aristocratic patrons, who adopted the classical style as the latest trend. A political chameleon, David adapted this Neoclassical style to remain successful throughout the tumultuous climate of the late-18th and early-19th centuries. He secured important commissions from the monarchy, the Revolutionary government, and Napoleon Bonaparte, all of whom used David's classicism to legitimize their claim to authority.

- Although he is most often identified with his activities during the French Revolution, during which he served on the National Council and organized propaganda, David was adept politically and adjusted his art to fit the needs of each of his patron. This ability provided an example for working with contemporary subjects and of modifying to fit different political engagements.

- The Academy taught drawing; to learn to paint, students would apprentice in the studio of a master. David's studio became the most important training ground for artists of the late-18th and early-19th centuries. Although many of his students would eventually rebel against this model and turn towards the burgeoning Romantic movement and its spiritual questioning, his legacy was established through generations of artists who could trace their instruction back to David's studio - his most famous student was Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Important Art by Jacques-Louis David

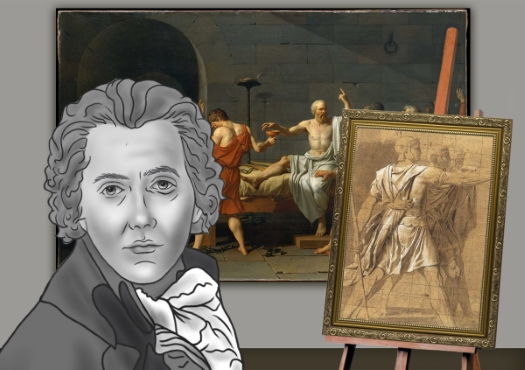

The Oath of the Horatii

The Oath of the Horatii depicts narrative from early Roman history. On the left, three young soldiers reach toward their father, pledging to fight for their homeland. They appear resolute and unified, every muscle in their bodies is actively engaged and forcefully described, as if to confirm their selflessness and bravery. These Roman Horatii brothers were to battle against three Curatii brothers from Alba to settle a territorial dispute between their city-states. They are willing to fight to the death, sacrificing themselves for home and family.

Underscoring their moral integrity, David compares their positive example with weakness. On the right, women and children collapse on each other, overwhelmed by their emotions and fear. Indeed, the women are more conflicted; one, a Curatii, was married to one of the Horatii while a Horatii sister was engaged to another of the Curatii. As they watch this dramatic pledge, they understand that either their husbands or their brothers were going to die and their loyalties are divided. David juxtaposes these two family groups, dividing the canvas not only into male and female roles, but contrasting the heroic and selfless with the fearful and uncertain.

This clarity is also reflected in the severity of the composition and style; while earlier artists had begun to mine Greco-Roman narratives as a fashionable trend in art, no other artist united these stories with David's stylistic minimalism and simplicity. The bare stage-like setting, organized by the sparse arches in the background, provides no distraction from the lesson being taught. Every figure and object in the painting contributes to this central moral.

Indeed, David even invented this scene to most concisely convey the essence of the narrative and its moral implications. In neither the written history, nor the 18th-century stage production of this story, do the sons pledge an oath to their father. David added this element because it allowed him to condense the larger epic into a singular moment, and to create the strongest possible emotional charge.

The enthusiastic reception of this painting at the Salon cemented David's reputation as the leading artist in the new Neoclassical style. Although the work was his first royal commission, and its emphasis on selflessness and patriotism was conceived with the monarchy in mind, its depiction of fraternity and heroic sacrifice would soon resonate with the French Revolution of 1789.

Oil on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

The Death of Socrates

Another narrative of stoic self-sacrifice and dignity, David presented the suicide of Socrates as an admirable and noble act. Set in the bare scene of his prison cell, the muscular body of the aged philosopher is meant to convey his moral and intellectual fitness. He sits upright, preparing to swallow the bowl of poisonous hemlock without any hesitation or uncertainty; he would rather die than renounce his teachings. His arm is raised in an oratory gesture, lecturing until his last moment, while his students demonstrate a range of emotional responses to his execution.

David's painting draws from Plato's account of the event, linking this painting with a classical source; yet, as in The Oath of the Horatii, David takes artistic license to manipulate the scene for greater dramatic effect. He eliminates some of the figures mentioned in Plato's account and idealizes the aged figure of Socrates, making his message of heroic logic and intellectualism clear to the viewer.

As tensions rose in pre-revolutionary France, David's depiction of resistance against an unjust authority quickly became popular. In a letter to the famous British portraitist Sir Joshua Reynolds, the artist John Boydell claimed it to be "the greatest effort of art since the Sistine Chapel and the stanza of Raphael."

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of his Sons

In the dark shadows that fall across the lower left corner, sits a man on a bench; looking out at the viewer, his facial expression is difficult to decipher. Separated from the rest of the composition by this darkness, as well as a Doric column and silhouetted statue, the viewer's eye moves from him to the brightly lit, dramatically posed woman to the right. Her two children cling to her, as she reaches out an arm, a movement that is balanced by a figure in blue who has collapsed. Following this outstretched arm, the viewer finally arrives at the titular subject - the light falls upon a corpse being borne on a stretcher. The circuit connecting these three main actors: Brutus, his wife, and his dead son, is a tight circle, creating through light and gesture.

David uses these two fundamental components to succinctly retell a story from Roman history; here, Brutus, a father, has sentenced to death his two sons because of their treasonous actions. His patriotism was greater than even his love for his family, although his stoic grief reveals the dear cost of this conviction.

This painting, with its messaging about patriotism, loyalty, and sacrifice, was due to be exhibited at the Salon in the earliest days of the Revolution. The royal authorities, still in control of the exhibition, examined each work to ensure that it would not contribute to the political instability and further jeopardize the stability of the monarchy. One of David's paintings, a portrait of a known Jacobist, was refused, as was this charged depiction of Brutus. When this was announced, there was a public outcry; the painting was ultimately displayed under the protection of David's students. The painting inspired a passionate following and permeated popular culture; this work was even re-enacted with live actors from National Theatre following a November 1790 performance of Voltaire's Brutus.

Oil on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

Oath of the Tennis Court

To mark the first anniversary of the Tennis Court oath, a moment of solidarity that sparked the revolution, David began an ambitious project. The monumental scale of this planned painting required nearly life-size portraits of the main actors. In this preparatory drawing, he included depictions of key leading figures, including Jean-Sylvestre Bailly and Maximilien Robespierre.

History painting had traditionally been the highest genre of painting, but was limited to the distant past. This project was innovative in its focus on contemporary history. When the drawing was exhibited, however, it was met with mixed reviews. While one supporter called David "the King of the learned brush," some of the Revolution's opponents found it offensive, bordering on treason for its celebration of the defiant insurrectionists; France was, at the time of this preparatory work, still operating under the limited powers of Louis XVI.

Its contemporaneity was its downfall: by the time David was prepared to begin the paintings, the volatile political situation had shifted. With the dawn of the Reign of Terror, many of the principals featured in the work were considered enemies of the state and would soon be executed. The Tennis Court oath was no longer a celebrated moment of Revolutionary history and plans for its commemoration were forgotten. Only partial sketches remain for a monumental, but aborted, commemoration of this first victory of the people.

Pen and brown ink, brown wash with white highlights - Collection of Musée du Chateau de Versailles, Versailles, France

The Death of Marat

Once more turning to contemporary politics, David was commissioned to create a memorial to Jean-Paul Marat following his 1793 assassination by Charlotte Corday. A French politician, physician, journalist, and a leader of the radical Montagnard faction, Marat had been murdered while sitting in a medicinal bath that alleviated the symptoms of a painful skin condition. David's painting combines such factual information (including a legible version of Corday's deceptive plea, calculated to gain an audience with Marat) along with highly symbolic elements of propaganda to create an image that elevates Marat to martyrdom. Sometimes referred to as Marat Breathing his Last, we see the humble workspace of a tireless public servant: only his bath and a simple box that serves as his writing desk.

This sparse composition forces the viewer to contemplate the body of Marat, which appears peacefully splayed. The knife wound, visible on his chest, is barely indicated and only glimpses of the bloody bathwater hint at the preceding violence. Although the Revolutionary government had outlawed religion, David created a visual analogy between Marat and images of the dead Christ. The graceful sweep of Marat's arm mirrors Michelangelo's Pieta and other scenes of the Deposition from the Cross; the white turban wrapped around Marat's head serves as a proxy for a halo.

David's clear sympathies for Marat and his transformation of the politician into a timeless martyr made this painting became highly problematic after the fall of the Jacobin government; it was returned to David in 1795 and remained in his possession until his death. Hidden from view, it was only rediscovered in the mid-19th century, when it was celebrated by the poet Charles Baudelaire.

In the 20th century, David's iconic memorial to Marat was a touchstone for artists engaged with politics. Edvard Munch and Pablo Picasso both did versions of the painting, as did the Chinese painter Yue Minjun. The socially conscious Brazilian artist, Vik Muniz, used David's painting as inspiration for one of his Pictures of Garbage series; in these works, he traveled to the world's largest landfill, Jardim Gramacho (located outside of Rio de Janeiro) to work with the catadores, people who picked through garbage, transforming the detritus to recreate great masterpieces, including David's painting.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, Belgium

The Intervention of the Sabine Women

Painted during the waning years of the Revolution, David's The Intervention of the Sabine Women suggests the nation's fatigue and a growing desire for peace. Indeed, while the subject is taken from Roman history, it represents a different type of narrative, highlighting the role of the Sabine women in bringing peace between their countrymen and the Romans. Coming after years of conflict, following the Roman abduction of these women, it represents a complicated scene with multiple loyalties in play. The analogies to the post-Revolutionary government are clear.

From a technical perspective, this work features a much more complex narrative. The focus rests on the bare-chested woman in white, but a number of emotional vignettes compete for the viewer's attention. This represents a change from David's earlier, more singular plots, and demands a new approach to looking at the painting in stages. In the original exhibition of the piece, David broke with tradition by placing a mirror on the wall opposite the painting. In this modern installation, the traditional idea of viewer engagement was radically shifted. Onlookers could turn away from the work and see it reflected in the mirror, which would enhance the experience by allowing the viewers to feel that they were part of the action itself. This participatory quality would become a central concern for artists of the 20th century.

In 1972, the Italian artist Luigi Ontani, based a performance on this painting. After David (The Rape of the Sabines) included Ontani as one of the nude Roman soldiers, holding a reproduction of the painting. He intended the work to encourage viewers to consider the behaviors of past civilizations.

Oil on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

Bonaparte Crossing the Grand Saint-Bernard Pass, 20 May 1800

An image of absolute control, confidence, and optimism, Bonaparte Crossing the St Bernard Pass is a large-scale equestrian portrait of the ruler. Shown heroically conquering this inhospitable terrain, Napoleon secures his place in history alongside two other generals who found victory in this same difficult military approach; their names are inscribed on the rocks in the lower left corner: Hannibal, and Charlemagne.

Napoleon had come to power through a military coup in 1799, declaring himself First Consul and seizing command. This painting represents this bold general and his ability to maintain control in the face of chaos and danger. Although the horse rears up on the edge of a rocky precipice, Napoleon calmly holds the reins in one hand while gesturing forward with his other arm. The movement of the horse is echoed in the flowing golden yellow cape of Bonaparte. Everything about the leader suggests a forward trajectory, highlighting his ability to lead France above the turmoil of the Revolutionary period. While David had supported the Revolution, he committed himself to the new French leader Bonaparte (who had restored David's reputation and financial success) and painted many portraits of the general that helped to legitimize his claim to authority.

This work was commissioned by King Charles IV of Spain, who admired the leader and was relieved at the restoration of order to neighboring France. The actual moment depicted was entirely fictitious: although Napoleon led his troops over the Alps, he rode a mule through a narrow mountain trail (as the soldiers in the distance are shown). Indeed, Napoleon even refused David's request to sit for the portrait, stating, "No one knows if portraits of great men are likenesses: it suffices that genius lives." Instead, David used models wearing Napoleon's clothes to pose for the hero. The painting originally was displayed in the Spanish royal palace, but Napoleon quickly ordered three copies for himself. David was subsequently named First Painter to Napoleon in 1801 and he, and his students, would provide official portraits and propaganda throughout the emperor's reign.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Musée National de Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison, France

The Coronation of the Emperor and Empress

The December 2, 1804 ceremony that named Napoleon Bonaparte Emperor of France was an elaborately choreographed affair. Wanting to recreate Charlemagne's coronation as Holy Roman Emperor, the presence of the Pope was requested. Famously, at the last moment, Napoleon took the crown from Pius VII hands and crowned himself; but this audacious act was not the subject of David's monumental painting, The Coronation of the Emperor and Empress. Instead, David chose the less controversial moment when Napoleon crowned his wife, Josephine, in front of a crowd of dignitaries in Notre Dame Cathedral. The epic scale of this painting (at nearly 30 foot long, the majority of the portraits were life-size) spoke to Napoleon's desire to legitimize his reign through displays of grandiose power.

David characteristically enhanced the actual event to greater dramatic effect. For example, Napoleon's mother appears as a central figure at the event, seated in one of the main boxes, although she was not actually present at the coronation. Details of the opulence and magnificence of the event, however, were carefully recorded to create a document attesting to Napoleon's political power. Napoleon does seem to upstage the Pope here, too, as the center of attention and the most active figure in the composition. With this highly prestigious commission, David not only reasserted himself as a leading painter in France, but in its abundance of detail and contemporary nature, he demonstrated his ability to manipulate his classical style to suit very different depictions.

Oil on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

Mars Disarmed by Venus and the Three Graces

Mars Disarmed by Venus and the Three Graces was David's last painting, one he intended to be a final statement about his oeuvre. When he began it in 1821, he announced, "It is the last of the paintings I want to do, but I want to surpass myself in it. I will inscribe it with the date of my seventy-fifth year, and after that I never want to touch a brush again."

Exiled in Belgium and in failing health, one is tempted to read his choice of subject as a nod towards reconciliation and peace. Venus, goddess of love crowns the god of war, Mars, her hand perched suggestively on his thigh. While the subject is drawn from Roman mythology and the paint handling is linear and crisp, the painting differs radically from the examples of his earliest and most famous years. Set in a decorative and fantastical heavenly space, David's heroic man is supplanted by the dominant figure of a reclining female nude. Both the narrative and the composition are more feminine than masculine.

For years, scholars considered this work to be an example of David's declining faculties; his late work was derided as inferior and often omitted from serious discussions of his career. Yet, it is possible that David chose to reinvent his style for his last painting to demonstrate his continued relevance to an art world that had abandoned Neoclassicism in favor of Romanticism. David's own student, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, was gaining attention at the time for his languid female nudes and there was new preference for more literary and imaginary subjects. If we consider the painting in this context, David's ability, at this late hour of his life, to evolve beyond his typical style, speaks to heart of modernism and its ever-changing nature.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, Belgium

Biography of Jacques-Louis David

Childhood and Education

Born in Paris to a wealthy family, Jacques-Louis David was raised by his mother's two architect brothers and educated at boarding school following the death of his merchant father in a pistol duel when the future artist was only nine years old. David defied his family's hopes that he too would train to be an architect or pursue a career in law or medicine by deciding to become an artist.

Early Training

The hugely famous Rococo artist François Boucher was a relative of David's, and arranged for the young artist to study with the more fashionable artist Joseph-Marie Vien, believing them to be of compatible styles. While a student, David was maimed during a fencing match with a colleague, a facial injury that compounded a speech impediment. The wound eventually became a non-malignant tumor that made his speech even more difficult and resulted in a visible deformity to his face.

In 1766, he enrolled at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. Determined to win the prestigious Prix de Rome (which funded a residency in Rome), he was initially unsuccessful in his pursuit. Not a gracious loser, David tried to starve himself to death after losing one attempt and openly disliked the artist, Joseph-Benoît Suvée, who won the prize, calling him at a later date "ignorant and horrible." He feared that the judges were against him, developing a paranoia that lasted throughout his career. He endured the long and difficult competition five times before winning and upon receiving this coveted price in 1774, he was said to have remarked, "This is the first time in four years that I have begun to draw breath."

While in Rome, David received his first commission, an altarpiece, St Roch Interceding with the Virgin for the Plaque Stricken (1780), which brought him great recognition. Realizing that his reputation had been made, he then turned down a scholarship to remain in Rome for another year, returning to Paris to start his career.

Mature Period

In Paris, David was known for his art and his bold, sometimes controversial behavior, which was often at odds with the French Royal Academy. Despite his arrogance and his failure to follow proper procedures for exhibiting his paintings, the detailed execution of his works and their highly dramatic narratives made him the leader of the new classicizing style. This built upon mid-century criticism of the Rococo, which catered to aristocratic tastes with decorative, often immoral, paintings of leisure. Denis Diderot had been particularly outspoken about the need to redefine art as an educational tool that conveyed proper civic virtues to a wide audience. David's style even attracted the attention of future American president Thomas Jefferson, then in Paris as the American minister to France; after seeing the Salon of 1787, Jefferson declared, "The best thing is the Death of Socrates by David, and a superb one it is."

The wealth of David's wife Suzanne, with whom he would have four children, helped support their family, along with the fees he received for portraits of wealthy and prominent French families, as well as his royal commissions. As a member of the Academy, David took on many pupils with one of the most popular painting studios where young artists could apprentice. This "School of David" would spawn the next generation of French painters, although many of them would rebel against the style of their teacher. In turn, David was not above petty jealousies when a student received too much recognition or David perceived they were threatening his own artistic standing.

Today, David is often associated with the French Revolution of 1789, yet, while The Oath of the Horatii (1784) became a visual symbol of the people's struggle, it was painted for a royal patron years earlier. Eventually, he became a full-fledged participant in the Revolution, aligning with the radical Jacobin party. As a member of the National Convention, he oversaw the death of former friends who resisted Revolutionary ideals. He even voted in favor of the execution of Louis XVI; at this, his wife left him.

He also used his art to support and celebrate the Revolution and its heroes, most famously Jean-Paul Marat. His memorial painting of the assassination of Marat would become a central image of Revolutionary sacrifice and propaganda. David's writings reflected his enthusiasm to serve: "I am making it my duty to answer the noble invitations of patriotism and of glory that will consecrate the history of the most felicitous and most astonishing Revolution." David would also organize events, such as the processional relocation of Voltaire's remains to the new Pantheon.

David's alliance with the Jacobins soon became a liability, however; he was arrested for treason in August 1794. Due to ill health and a fear that he would try to commit suicide, he was released from prison prior to being granted amnesty in October 1795.

Later Period

While in prison, David's eyesight began to weaken, yet his personal and professional life did not suffer. His former wife returned and they remarried in November 1796. In December 1795, he was nominated to the Académie de peinture et de sculpture, which had replaced the Royal Academy as the central art institution in France. His work was in demand again, in part because he had gained the favor of the new leader of France, Napoleon Bonaparte. In December 1803, Napoleon named the artist as a Knight of the Legion and commissioned a work commemorating his coronation as Emperor.

This political association would lead to David's exile when Napoleon fell from power in 1815. David had no place in the Restoration monarchy; King Louis XVIII's government persecuted those who had supported Napoleon and as a result David was exiled from France. In January 1816, he and his wife settled in Brussels, where he spent the rest of his life.

Despite failing health he continued to work, taking commissions for portraits and completing his last great painting, Mars Disarmed by Venus and the Three Graces in 1824. At this time some of his students tried to negotiate his return to France, but angry at the country that had turned him away and perhaps aware that Neoclassical style was no longer in fashion there, he refused any attempt. He even rebuked one student who had requested his signature on a petition for amnesty, stating, "Never speak to me again of things I ought to do to get back. I do not have to do anything; what I ought to have done for my country I have already done. I founded a brilliant school; I painted classic pictures that the whole of Europe came to study. I have fulfilled my part of the bargain; let the government now do the same."

David died in Brussels in 1825; his wife, also in poor health, had returned to Paris for medical treatment and was not with him in his final days. The French monarchy refused to allow his body to be returned to France for burial. Allegedly, after his wife died, their son secretly placed David's heart in her coffin, and she was buried in Paris. As part of the 200th anniversary of the Revolution, the French government tried to repatriate David's remains in 1989, but the Belgian government refused based on the argument that his grave had become a historical monument.

The Legacy of Jacques-Louis David

David used his art to sway political opinion, curry favor with government regimes, and fuel uprisings. His direct political involvement brought history painting in contact with current affairs. This immediacy would inspire later artists to represent the contemporary world, although the Romantics (many of whom were David's students) would radically reimagine the engagement to criticize those in power, rendering more emotionally laden narratives in a more painterly style.

Indeed, David's impact on modernism is most evident in his influence on Romanticism; the latter movement was directly connected to the rise of Modern Art. Romanticism grew directly out of Neoclassicism; its rejection of the clear moral universe and pictorial precision of Neoclassicism was equally a rejection of David's teachings. His students shifted away from the severe narratives of David to more sensuous and complicated Greco-Roman histories and mythologies, providing the first stirrings of Romantic painting.

In turn, artists such as Paul Cézanne and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who were directly influenced by Romanticism, can be connected back to David and his studio. In the 20th century, David's work was such a centerpiece of canonical art history that it was often referred to by artists who wished to make clear political statements while drawing upon the history of art, including Vik Muniz and Yue Minjun.

Influences and Connections

- Denis Diderot

- Jean Baptiste Publicola Chaussard

- Alexandre Lenoir

-

![Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres]() Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres -

![Théodore Géricault]() Théodore Géricault

Théodore Géricault - Jean-Germain Drouais

- Anne-Louis Girodet

- Yue Minjun

- Jean Baptiste Publicola Chaussard

- Alexandre Lenoir

Useful Resources on Jacques-Louis David

- DavidOur PickBy Simon Lee

- Jacques-Louis David, Revolutionary Artist: Art, Politics, and the French RevolutionBy Warren Roberts