Summary of Charles Demuth

A larger-than-life figure who is remembered nearly as often for his wit as he is for his paintings, the bold and insatiably curious Charles Demuth wasn't just a product of America's transformative early-20th century; he was one of its archetypes. Demuth was a principal member of the Precisionist movement that emphasized sharp lines and clear geometric shapes. Challenging the boundaries of race, class, sexuality, and artistic tradition, he digested the shifting social landscape around him and left behind a memorable body of work that defies categorization.

Accomplishments

- Demuth's brilliance is in the way he emphasized distinct colors and shapes out of elements that are more often relegated to the background, such as the factory smoke in Incense of a New Church (1921), or that may be considered too dull or commonplace to paint at all, such as typography in I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold (1928). Some of these would go on to influence the design of movie and theater posters, book dust jackets, and other visual media for decades to come.

- Like his friend and contemporary Georgia O'Keeffe, Demuth focused with intensity and precision on flowers and other vegetation. Unlike O'Keeffe, he stripped them down to precise geometric shapes and bold colors, imposing form and specificity on the chaos of the organic.

- Demuth's cheeky and evocative (and private) paintings of early-20th-century American gay subculture are among its few surviving visual records, and his jazz portraits celebrate the power and dynamism of the Harlem Renaissance.

Important Art by Charles Demuth

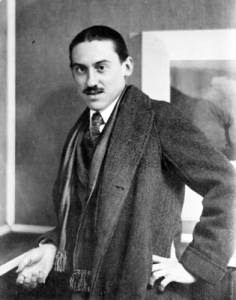

Self Portrait

Demuth painted this self-portrait while he was studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). 23 years old, he depicts himself as a pensive, thoughtful young man. While the details of his face and hair are captured in painstaking detail and nuance, his clothing is less distinctive, and gives way to a looser, unfinished rendering of his jacket toward the bottom of the canvas. His eyes do not directly meet the gaze of the viewer, and instead look slightly downward and to the right. The style of the portrait demonstrates how the instructors at PAFA - among them Thomas Anshutz, William Merritt Chase, and Hugh Breckenridge - instilled within Demuth an early reverence for a traditional, European approach to art. This early self-portrait is somewhat reminiscent of the work of John Singer Sargent, though Demuth would go on to develop his own distinct style. This painting was the only work ever exhibited in his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, during his lifetime.

Oil on Canvas - Demuth Museum, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

At Marshalls

During his regular visits to New York, Demuth would meet with friends at jazz clubs, basement bars, and hotel cafés. This sketchy, impressionistic watercolor depicts an evening he spent listening to jazz in the bar of the Marshall Hotel in the company of fellow artists Marcel Duchamp, Edward Fisk, and Marsden Hartley. It captures the energy of a night on the town: the men are smartly dressed, the room is smoky, and their faces are flushed with drink.

The Marshall Hotel, a black-owned hotel on West 53rd Street, was an important gathering place for New York's black elite, and among the first establishments where white, bohemian New Yorkers could come to experience the culture, music, and performances that would come to be known as the Harlem Renaissance. Demuth and his friends witnessed jazz in its infancy on nights like the one depicted here, and his images of these Manhattan hotspots were among the first to capture this pivotal period in America's cultural development. Jazz played a critical role in the development of American modernism, inspiring many of the nation's artists and writers to experiment and develop new forms of creative expression outside long-established European traditions.

Watercolor and Graphite on Paper - Demuth Museum, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Turkish Bath with Self Portrait

This watercolor sketch offers an illuminating depiction of the gay subculture in postwar New York. The setting is likely the Lafayette Baths, a Turkish bathhouse in the East Village. The artist, with dark hair and mustache, appears nude in the center of the frame. He talks with two other men: a blonde man swaddled in a towel, who faces away from the camera, and a fully undressed red-headed man who strikes a confident pose. Behind the trio, a man with indistinct features stands in a pool, water waist high, while a duo in the upper right corner of the canvas seem to be caught up in an intimate moment.

Demuth was likely open about his sexuality with his friends, and frankly depicted the evolving, underground gay scenes in New York and Paris. This image is striking in its open, candid depiction of desire and attraction between men. It was not intended for public exhibition during Demuth's lifetime and historically it has great significance, visualizing the emergence of a sexual subculture organized along very different lines than male/female courtship. Since his death, Demuth's watercolors of early-20th-century gay life have proven to be sources of inspiration and fellowship to later generations of American artists, including Andy Warhol, another Pennsylvania native.

Graphite and Watercolor on Paper - Private Collection

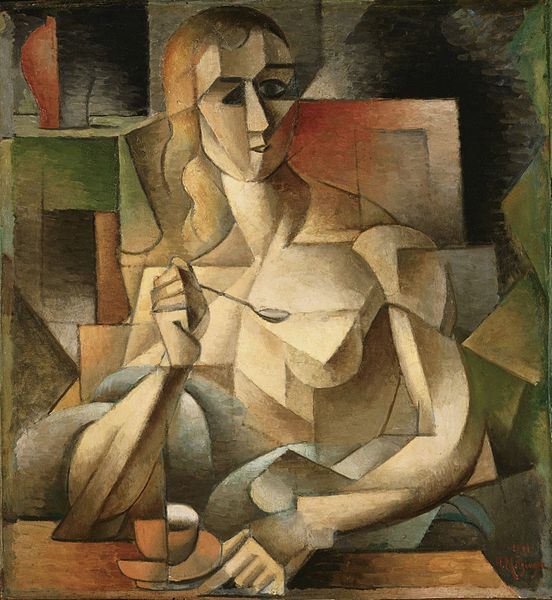

Incense of a New Church

Here, the vagueness of the city skyline is brought about not by any sort of physical blurriness, but by the use of simple, almost cartoonish patches of color that suggest darkness and obscure detail - even the plumes of industrial smoke are depicted geometrically. The cluster of clear shapes and colors depicts a dark, misty reality. This painting is a masterpiece of Precisionism, projecting form and structure onto organic and ambiguous phenomena, showing the influence of Cubism.

Critics tend to believe that the title Incense of a New Church holds self-evident meaning - the plumes of industrial smoke reminiscent of incense, the factories replacing the churches that once dominated the American cultural landscape. As a child Demuth could look up from his own backyard to see Lancaster's Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Holy Trinity, and would have had every reason to compare the factory town's shift from a landscape dominated by churches to one dominated by industry. Critics sometimes suggest that the title is meant to imply protest and a desire to return to the way things used to be, but there is little in Demuth's other work to suggest that he was in any way displeased with the emerging iconography of a more urban, secular world.

Oil on Canvas - Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, Ohio

Plums

Just as Demuth's Precisionist style brings out an organic character in industrial imagery, it teases the music of industrial geometry out of the organic. Note here the naked sharp boundaries of the leaves and branches, the minimal attention given to secondary light, the absence of any natural background, and the clinical, almost stark focus on the structure of the plum branch itself. It is not (and clearly does not aspire to be) photorealistic, but the painting's crispness conveys an essential shape, indigenous to the subject itself, that a photograph could not achieve. Demuth's flower paintings brought him commercial and critical success during his lifetime, but they receive relatively little critical attention today and unlike his well-known contemporary Georgia O'Keeffe, he did not become famous for them.

Watercolor on Paper - Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts

My Egypt

This enigmatic painting, one of seven in Demuth's final major series, depicts a concrete and steel grain elevator in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The massive structure looms over the smaller, red buildings nearby - perhaps barns or family homes - almost shoving them out to the sides and corners of the canvas. Several intersecting beams of light illuminate the grain elevator like an actor on stage, reiterating its importance while adding a geometric fracturing reminiscent of Cubism to the composition.

The painting has been interpreted as both a critique of modernization and a celebration of it. The title suggests that industrialization is a pinnacle of American achievement equivalent to the great monuments of the ancient world, evoking the pyramids of Egypt and their symbolic association with life after death, which may have been a compelling idea to Demuth, who was bedridden by illness at numerous points throughout his life. At the same time, the painting may also allude to the slave labor that built the great monuments to the pharaohs. Thus serving as a critique of the dehumanizing effect of industry on American workers.

Oil, Chalk, and Graphite on Board - Whitney Museum of American Art

I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold

Painted in homage to his friend the poet William Carlos Williams, this painting has become one of Demuth's best-known works. It references Williams' poem The Great Figure, which describes a fire engine speeding through the streets on a rainy night. The intersecting lines, planes of color, and round forms of the streetlights and the fire engine's blaring siren infuse the painting with a vibrant, urban energy.

The painting's title is a phrase from the poem. Williams and Demuth met as students in Philadelphia in their early twenties, and were close friends throughout their lives. An iconic work of Precisionism - the geometric planes of light and color that overlap various elements of the composition suggest European Cubism and Futurism, yet their sense of scale and directness of expression are entirely American.

Oil on Board - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Distinguished Air

This amusing watercolor depicts a small crowd: a woman in a bold, low-cut dress on the right, two men at the center, and a man and woman at the right. Inspired by a scene from a short story by the American writer Robert McAlmon, which takes place in a "queer café" in Berlin, the onlookers view a sculpture by Constantin Brancusi, Princess X (1915-16). Demuth humorously accentuates the phallic form of Brancusi's bronze sculpture, which caused quite a scandal on its debut. While both women appear to be blushing and staring at the statue with open mouths, the man in the brown suit on the left is clearly more interested in appreciating the aesthetic charms of the sailor, who himself appears to be looking at his companion instead of the sculpture, or perhaps scrutinizing the woman in red. The painting evokes the underground culture of sexual freedom and expressiveness within Europe's artistic and bohemian circles during the First World War, and gives the viewer a glimpse of Demuth's witty personality and fondness for blue humor.

Watercolor and Graphite on Paper - Whitney Museum of American Art

Biography of Charles Demuth

Childhood

Charles Demuth was the only child of Ferdinand and Augusta Demuth, long-term residents of Lancaster. He grew up in a house next door to the family tobacco shop on East King Street, which his father's family had owned since 1770. When he was four years old Demuth injured his hip and was bedridden for several weeks. His mother gave him crayons and watercolors to keep him entertained, and this marked the beginning of his love for art. As art would become a major feature of his life, so too, unfortunately, would illness. His injury made it necessary for him to use a cane and he walked with a pronounced limp. Though he was close to both his parents, his physical frailty meant that he was particularly dependent on his mother. He became socially withdrawn at school, preferring to play with girls over boys, as his mother and aunt had warned him that rough play with other boys could cause his injury to worsen. Both his parents supported his interest in painting and drawing from an early age - his father was an amateur photographer himself.

After his hip injury began to heal and he was no longer bedridden, his parents sent him to Martha Bowman for private art lessons in still life and landscape painting. As a child and young man, he also trained with other local artists. His early sketchbooks reveal a formidable level of talent and dedication for someone so young. As financially secure merchants, Demuth's parents were consistently supportive of his desire to pursue a career in art.

Early Training

He attended Franklin and Marshall College and later pursued graduate study in art in Philadelphia, first at Drexel University and then at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. While at the Academy, he painted his first self-portrait in oil in 1907. William Carlos Williams (later renowned as a leading American poet of modernism and imagism) was living in the same boarding house and the two young men established a friendship which remained throughout their lives.

After leaving school, Demuth shifted away from painting in oil and began to favor watercolor as a medium. He was inspired, quite literally, by what he saw in his own backyard, producing paintings of flowers and his mother's vegetable garden. He was also inspired by his travels to New York City and Provincetown, Cape Cod, where he spent many summers from 1914 onward. Along with the playwright Eugene O'Neill, Demuth became one of the founders of the Provincetown Players, an influential theatre company that played a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of 20th century American drama.

During the rest of the year, he took the train to New York almost every week and developed friendships with members of the city's artistic elite, including Alfred Stieglitz, Marcel Duchamp, and Edward Fisk. He visited galleries, where he was exposed to the works of leading European and expatriate artists. He also enjoyed the city's nightclubs and jazz bars, and the creative, bohemian atmosphere of the Harlem Renaissance and Jazz Age New York began to appear in his paintings. Although he spent a great deal of time in New York City and Provincetown, Lancaster remained Demuth's home throughout his life, his art rooted in his perception of it as a typically American town, albeit one that shifted to reflect changing times.

Mature Period

His artistic success enabled him to travel when his health permitted it, and in the winter of 1915-1916 he rented an apartment on the south side of Washington Square Park, to draw inspiration from the vibrant creative atmosphere of Greenwich Village. In the late 1910s he made several trips to Paris where he met fellow artist Marsden Hartley, who he introduced himself to after overhearing an American accent at a bar. He quickly endeared himself to Hartley and his friends with his outgoing nature, willingness to poke fun at himself, and risque sense of humor.

Along with Hartley, Demuth traveled to Bermuda in 1917 and began a series of architectural and landscape paintings inspired by Cézanne, which heralded his first experimentations with Cubist and Modernist principles. These pieces formed part of an acclaimed exhibition in the fall of 1917 at the Daniel Gallery in New York, alongside the works of modernist painter Edward Fisk.

Demuth traveled to Paris repeatedly in the late 1910s and early 1920s. As a gay man, he found the city more open and accepting than much of the United States, and a number of his paintings - which were not intended for public view at the time he painted them - vividly depict the vibrant gay subculture of postwar Paris. The Lafayette Baths became one of his favorite haunts, and is likely the setting of a 1918 self-portrait. Yet his memories of Paris were not all happy ones: in September 1921, illness forced him to be admitted to the American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine. He was treated and released, but was too unwell to return to America until November. Back home in Lancaster he was diagnosed with diabetes and began experimental treatments, including a near-starvation diet and insulin injections.

Late Period

Having brought his diabetes under control, Demuth began painting the first in his series of "poster portraits" in 1923. These were symbolic interpretations of the works of fellow artists and writers, including Georgia O'Keeffe, Arthur Dove, John Marin, and William Carlos Williams. That same year, he became one of the first of his contemporaries to have work purchased for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's permanent collection. During the mid-1920s, he had several successful solo exhibitions and in 1927, the first book on his work was published, and he began his latest major series of seven paintings, based on the architecture of Lancaster. The paintings became iconic representations of the industrialization of small-town America and cemented Demuth's reputation as the leading painter of the Precisionist movement, the first home-grown modern art movement within the United States.

Accompanied by hometown friends Elsie and Frank Everts, Demuth made his final visit to Provincetown in 1934. During the trip he created some of his last works, sketches of beach scenes in pencil and watercolor. He died the following year in Lancaster at age 51 due to complications from diabetes. In his will, Demuth stipulated that many of his paintings should go to Georgia O'Keeffe, whose role in determining which museums received his works helped preserve and fortify his reputation. In the years after his death, Demuth's family home on East King Street in Lancaster became a museum dedicated exclusively to his art.

The Legacy of Charles Demuth

Demuth was a remarkably versatile painter. He was able to shift between delicate, light treatments of flowers or candid moments between friends in watercolor, to more tightly controlled geometric interpretations of the modern urban and industrial landscape. He was one of the first painters to give modernist form a distinctly American point of view, thus the significance of his work to the development of art in this country throughout the 20th century cannot be overstated. The influence of his industrial landscapes can immediately be seen in the works of Charles Sheeler, Stuart Davis, Gerald Murphy, and Ralston Crawford. By helping to develop an American offshoot of modernism, Demuth became a forerunner to later movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Pop art.

Influences and Connections

-

![Alfred Stieglitz]() Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz ![William Carlos Williams]() William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams

-

![Georgia O'Keeffe]() Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe -

![John Marin]() John Marin

John Marin -

![Charles Sheeler]() Charles Sheeler

Charles Sheeler -

![Stuart Davis]() Stuart Davis

Stuart Davis ![Gerald Murphy]() Gerald Murphy

Gerald Murphy

-

![Marsden Hartley]() Marsden Hartley

Marsden Hartley ![Charles Daniel]() Charles Daniel

Charles Daniel

Useful Resources on Charles Demuth

- Charles DemuthOur PickBy Barbara Haskell

- Charles DemuthBy Alvord L. Eiseman

- Letters of Charles DemuthOur PickBy Bruce Kellner

- Chimneys and Towers: Charles Demuth's Late Paintings of LancasterBy Betsy Fahlmann and Claire Barry

- Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the Art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and the First American Avant-GardeOur PickBy Johnathan Weinberg

- Precisionism in America 1915-1941: Reordering RealityBy Diana Murphy