Summary of Childe Hassam

Childe "Muley" Hassam enjoyed the mystery surrounding his moniker. Playing off the confusion from his surname as to whether he was of Arabic descent, Hassam adopted "Muley," a corruption of the Arabic word for "master," in reference to a 15th-century Moorish ruler who appears in Washington Irving's writings. The nickname is fitting, since Hassam's stature as one of the giants of American Impressionism has remained unchallenged since his death. Influenced greatly by French painters of the 1870s and 1880s, Hassam turned his art into an industry that mirrored the rapid industrialization of America at the turn of the 20th century. In hundreds of works, he strove to depict both the frenzied pace of city life as well as the unspoiled expanses of nature that provided a respite from the urbanization, propagating a certain pride in the nation's past as well as present.

Accomplishments

- Hassam's work, like that of the French Impressionists, is intimately concerned with the interaction of light, weather, and surface, especially as they change with the movement of elements within the scene, and often in concert with the frenzied pace of modern urban life. But unlike the French, Hassam avoids uncomfortable political issues in favor of an optimistic view of American industriousness and rural charm.

- Hassam treated his art much like a business, aggressively marketing himself and churning out canvases and works on paper by the carload, and gathering associations of artists around him to increase his notoriety. His efforts paid off, as he built a sizeable reputation and fortune over a career spanning more than fifty years.

- While Hassam helped create a strand of Impressionism that was distinctly American, he remained connected with the European Art of the 1870s and '80s for the bulk of his career, and frequently maintained ties to foreign lands through his travels; the culmination of his patriotic internationalism is his series of flag paintings supporting the allied cause during World War I.

- Hassam's devotion to Impressionism was impressive, as he steadfastly refused to adapt to the innovations in modern art coming from Europe starting in the 1910s, instead ridiculing non-representational abstraction in painting even after its acceptance as cutting-edge modernism by American critics in the interwar era.

Important Art by Childe Hassam

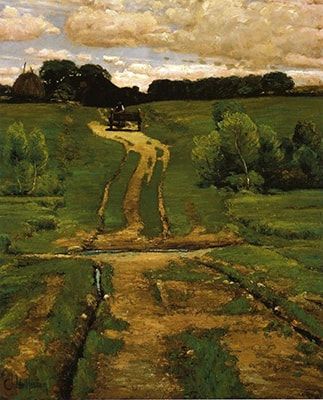

A Back Road

A Back Road most significantly reveals the influence of the Barbizon School painters on Hassam. The expansive, agricultural landscape (suggested by the haystack in the distance), wagon, and cloud-filled sky all recall the rural farm scenes of these midcentury French painters, whose work Hassam would have seen on his first trip to Europe in 1883. In Hassam's painting, the sense of stillness and the heat of summer are coupled with an acknowledgment of the vastness of nature that dwarfs the human scale. But unlike the Realist paintings of the Barbizon School, whose content focused on the downtrodden, hand-to-mouth agricultural existence of the French peasantry, Hassam's painting of a solitary laborer driving down a dirt path celebrates the American farming tradition and the lush foliage of the countryside. Here the irregular, winding trail, partly encroached upon by patches of grass, suggest both the power of nature and the struggle of man to carve out his place within it.

Oil on canvas - Brooklyn Museum, New York

Rainy Day, Columbus Avenue, Boston

One of the last paintings that Hassam completed before leaving America in 1886 for three years in France, this work depicts an intersection near the artist's apartment in Boston's South End during the titular weather. But the importance of the work lies in Hassam's ability to explore simultaneously the literal intersection of his numerous artistic interests. Hassam had taken a brief trip to Europe in 1883, including Paris, where he had seen works by the French Impressionists, and Rainy Day, Columbus Avenue also suggests Hassam's shared preoccupation with several of their themes, principally the interplay of light, weather, bodies, and surfaces, and their combined effect upon the naked eye's perception under such conditions. The wide angle of the scene also suggests Hassam's interest, like his French counterparts, in photography, and perhaps particularly stereo-views or panoramas created by multiple photographs joined together in series.

Although Hassam probably did not see Gustave Caillebotte's Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877) specifically when he had visited France, it is virtually impossible not to compare the two works. Along with identical weather conditions, the paintings' scenes use strikingly similar architectural settings, with three primary rows of buildings receding into the distance, creating a dramatic, two-point perspectival system that moves the viewer's eye horizontally across the frame. Unlike Caillebotte's work, however, which is charged with complex symbolic overtones about the fragmentation of modern French society in the aftermath of Haussmann's transformation of Paris and the traumatic Franco-Prussian War, Hassam's work remains nearly empty of political undertones. In Rainy Day, Columbus Avenue Hassam creates an implicit comparison between Boston and Paris: the former as the city that nurtured his early career, and the latter where he would transition into a mature artist. Not surprisingly, Hassam liked this work so much that he selected it to be shown at the highly-regarded Society of American Artists exhibition in New York in 1886.

Oil on canvas - Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio

![Grand Prix Day [Le Jour de Grand Prix] (1887-88)](/images20/works/hassam_childe_3.jpg?1)

Grand Prix Day [Le Jour de Grand Prix]

This painting depicts a busy tree-lined street in Paris filled with horse-drawn carriages traveling in both directions, one of two identically-titled canvases capturing the parades that occurred in Paris to mark the beginning of the annual horse racing season. Its importance is revealed by Hassam's ability here to immediately synthesize the artistic developments then taking place in Paris. Much of the work is painted in loose brushstrokes like Impressionist works, but it is also evident that Hassam appreciated the pointillist works that Georges Seurat and Vincent van Gogh were beginning to exhibit upon the dissolution of the Impressionist circle. This nod to Seurat's work can be seen here in the sky and in the trees, where Hassam has juxtaposed small, nearly dot-like flecks of varied tones of color, thus creating more luminant regions that almost seem to glow. Much like this work represents a transitional phase in Hassam's career, between his period in Boston and later work in New York, it also serves as a documentation of the transition in avant-garde art at a precise moment, as well as the considerable artistic exchange of the era between Europe and North America, of which Hassam's work played a major part.

Oil on canvas - New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, Connecticut

Poppies, Isles of Shoals

Poppies, Isles of Shoals is characteristic of the many landscapes that Hassam painted when on vacation from New York - from the 1890s onwards. The Isles, off the Atlantic coast of Maine and New Hampshire, were a favorite spot for him as well as several other New England writers and cultural figures at the end of the 19th century, including William Morris Hunt. It was there that he formed a friendship with the poet and critic Celia Thaxter, whose gardens, along with the nearby shores and ocean, greatly intrigued Hassam.

Hassam's landscapes, seascapes, and still lifes, such as Poppies, illustrate well his ability to depict the effects of light and the intensity of color of the features of the land and sea, often packaged together in a harmonious ensemble. Here, he divides the canvas into three zones of nearly equal size: a band of the red and pink titular flowers in full bloom occupies the bottom third, while the island's rocky shores extend into the ocean in the middle, followed by the pale, sun-bleached sky at the top. The balance of the painting underscores the unchanging stillness of the scene, with little movement detectable; the viewer likely imagines sounds here such as the gentle lapping of waters among the rocks and perhaps a cry or two from invisible seagulls.

The pastoral quality of the scene provides a counterpoint to the bustling urban works that Hassam was churning out at a frenzied pace in New York. Poppies and its related landscapes thus represent an antidote to the hurried, crowded pace of modern life that increasingly characterized city-life-America at the turn of the century. Hassam seems to have stopped time at an ideal moment where the sun perfectly illuminates the hues of the flowers and shoreline, thus preserving them for posterity. Poppies thus serves as a reminder that America still guarded some unspoiled, tangible parcels of nature despite the massive, confusing energy of industrialization that was fast transforming its society.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Winter in Union Square

Winter in Union Square encapsulates Hassam's mature style of cityscapes after he returned to America from Europe in 1889. He quickly drew inspiration from the scenes of modern life as captured by the activity on the streets of New York, principally where he had settled around Union Square in lower Manhattan, which was quickly becoming the center of the city's commercial and cultural life. Hassam became engrossed in people-watching, and his paintings of New York from the turn of the century reveal his fascination with the movement of people through the urban environment. This painting is one of the first of many where Hassam chose an elevated vantage point for such a view, a strategy that both increases the drama of the scene and hints at the painter's power over his depiction of the environment.

Hassam became famous for his many depictions of this hub of human activity in the winter, when the inclement weather often created fascinating effects of light and texture. The loose brushstrokes that characterize Hassam's Impressionistic style illustrate this preoccupation well, suggesting the bustling struggle of New Yorkers negotiating their way through the snow on trolleys, in cabs, and on foot. At the same time, Hassam asks the viewer to consider the particular atmospheric effects on the perception of the trees, sky, and the architecture. Significantly, Hassam captures the ultimate symbol of modernity - the dome of the Domestic Sewing Machine Company's building, then New York's tallest - piercing the sky, as if documenting the collision between the accomplishments of man and the raw forces of nature that shroud and batter it.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Allies Day, May 1917

Hassam is well-known for his series of nearly thirty paintings completed between 1916 and 1919 depicting both the American flag and those of her World War I allies on display on the streets of New York City, particularly on Fifth Avenue. He painted them both to raise money for the war effort and to instill a sense of patriotism and solidarity among Americans. Many of them, such as Allies Day, are painted from Hassam's preferred elevated vantage point along the street, juxtaposing the colorful banners waving in the breeze with the staid, gray verticals of the architecture, forms often used by Hassam to represent an American character and identity. The decking of these structures with flags suggests the depths of American commitment to the Allied cause, akin to the notion of wrapping oneself in a national flag.

Like many of his other works, the flag series, including Allies Day, derives from several French models of public flag displays on festival days, such as Monet's Rue Montorgeuil, Fête de 30 juin 1878 (1878). But the flag paintings also represent a deeply personal strain of Hassam's Impressionism; each of the nations (with the exception of Canada, whose flag in the foreground contains the British flag on a red ensign) played a significant role in his life. A proud American, he was a noted Anglophile and received much of his artistic training in France. It is not surprising, then, that Hassam scoffed with disdain when he failed to find a buyer for the series as a whole in 1919 and realized the collection would be dispersed.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Biography of Childe Hassam

Childhood and Education

Frederick Childe Hassam's family had deep New England roots. His father was a cutlery salesman based in Boston whose ancestors arrived in America from England in the 17th century with a name that began as Horsham. This name went through a number of spelling changes before becoming Hassam, which would result in questions regarding the future artist's origin with some believing, much to Hassam's amusement, that he was Arabian.

Hassam's interest in art developed at a young age and one of his earliest memories was hiding in an antique coach his father collected, so he could paint undisturbed. His childhood talent was recognized by an aunt who encouraged him by arranging for him to meet with local artists.

The family suffered financially when, in 1872, his father's business was destroyed by a fire resulting in Hassam being forced to leave school and obtain a job to help support the family. Lasting only three weeks in the accounting department of a publishing company, his supervisor suggested upon Hassam's dismissal that since he spent all of his time creating drawings, he might consider a career in art. Taking this advice, Hassam obtained a job in a wood engraving shop, where he quickly rose to the position of draftsman.

Early Training

By 1881 Hassam had opened his own studio, working as a draftsman and freelance illustrator for children's books and magazines; he continued his art education by taking classes at the Lowell Institute and the Boston Art Club. In 1882, he had his first solo exhibition of around fifty watercolors at a Boston gallery, which included works depicting what would become one of his popular themes, landscape paintings of places he visited, such as Nantucket. In fact, travel would inspire Hassam's art throughout his career, including the first of many trips to Europe he made in 1883, where he drank deeply at the well of the French Impressionists.

In the early 1880s Hassam met poet Celia Thaxter, whose father owned the Appledore House hotel on the Isles of Shoals, Maine, where she lived and during the mid-to-late-19th century welcomed many New England cultural luminaries in a salon-like atmosphere, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Whittier, Sarah Orne Jewett, and William Morris Hunt. Hassam later described the group as a "jolly, refined, interesting and artistic set of people...like one large family." Hassam taught Thaxter to paint, and the crescent shape that began to appear in front of his signature on works of this period were believed to be a reference to Thaxter, who, in her poetry, linked a crescent sun to the artist's emerging fame. As time passed, the crescent was reduced to a simple slash that was later useful when Hassam proved a work considered to be his was a forgery due to the missing mark by his signature. Hassam would produced numerous canvases and watercolors depicting Thaxter's extensive gardens and the islands' seashore.

Hassam had courted Kathleen Maude Doane, a family friend, for several years and finally married her on February 1st, 1884. The new couple moved into an apartment in the South End of Boston, and Hassam's work took on a new focus, the depiction of city scenes. With works such as Rainy Day, Columbus Avenue, Boston (1885), he also demonstrated a fascination with city life, perspective, and the atmospheric effects of weather and light.

Mature Period

In the autumn of 1886, Hassam and his wife left Boston for a three-year stay in Paris, where he studied at the prestigious Academie Julian and completed a series of urban and garden scenes. Upon his return, the Hassams settled in New York City where he helped to found the New York Water Color Club. An interesting character, Hassam was known for his dapper style, often wearing tweed suits and sometimes even a monocle.

Shortly after arriving in New York, Hassam met fellow artists John Twachtman and J. Alden Weir at the opening reception for an exhibition of the American Water Color Society. The friendship between the three was in part bonded over a shared affection for and desire to create Impressionist works. This focus was deepened by a friendship with Theodore Robinson, who had worked in Giverny, France with Claude Monet. During this time the group of artists would go together to study works by Monet and other Impressionist masters, such as Edgar Degas and Auguste Renoir, that were on view throughout the city.

Drawing inspiration from city life, Hassam spent the majority of his days traveling through New York City painting the sites, sometimes using a stopped carriage as a studio with an easel set on the seat across from him. During this time, in part inspired by the work of the French painters he had studied, Hassam's work focused on the effects of light on objects which he captured in loose brushstrokes with deliberate color choices. As a result, he would become one of the leaders of American Impressionism, a style that was met with both positive and negative reviews by critics and the public alike.

Later Period

From the late 1890s onward, Hassam's style became even more impressionistic with quick brushstrokes that were so thin, one could sometimes almost see the canvas beneath. The increasing modernity of the city with the newly built skyscrapers, along with new summer locations he visited such as East Hampton, Long Island where Hassam would eventually buy a home, provided exciting subjects for the artist.

In a debate over the importance of Impressionism, in December 1897, Hassam and nine other painters left the Society of American Artists to form the Ten American Painters. When this new group began exhibiting their works it was Hassam who was often viewed as the most radical, with one critic writing, "Hassam is as impressionistic as the most extreme could wish."

The outbreak of World War I provided a source of inspiration late in Hassam's career and resulted in the creation of many patriotic-themed works as well as a brief arrest when he unknowingly broke the law by drawing the naval training taking place on the Hudson River. The war was the theme of one of Hassam's greatest series, paintings of American and other flags that lined the many streets of New York City during these years. Capturing the intense patriotism of the period, the works helped raise funds for the war effort while simultaneously raising the American spirit. Despite his best efforts, after the war's end Hassam was unable to keep the nearly thirty flag paintings together as a memorial. Angered by this he wrote in 1919, "I have heard it before!! Nobody ever heard of New York subscribing anything for the fine arts... They [the flag paintings] will probably be sold in the west somewhere - and the enthusiastic New Yorkers will have to pay railroad fare to go and see them! I don't care a damn what you do about it."

Despite his emergence as one of the leaders of a new American art movement, near the end of his life Hassam became increasingly vocal against developing styles of modernism as well as European artists. Battling failing health and increased bouts of drinking, he continued to paint until his death in 1935.

The Legacy of Childe Hassam

Childe Hassam proved quick to pick up on the latest developments in European art in the 1880s and worked assiduously to adapt it to the depictions of modernizing, industrializing America. Yet he also remained a devotee of Impressionism even long after it had been superseded as cutting-edge by other movements in modern art. Hassam's work helped to pave the way for other artists such as Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield, and Andrew Wyeth, who, while they differed from him stylistically, remained committed to developing a home-grown, distinctively American subject matter.

Influences and Connections

![Celia Thaxter]() Celia Thaxter

Celia Thaxter

Useful Resources on Childe Hassam

- Childe Hassam: American ImpressionistOur PickBy Ulrich W. Hiesinger

- Childe Hassam: American ImpressionistBy H. Barbara Weinberg

- American Impressionist: Childe Hassam and the Isles of ShoalsBy Austen Barron Bailly and John W. Coffey

- Childe HassamOur PickBy Donelson F. Hoopes

- Childe Hassam, American Impressionist (Metropolitan Museum of Art Series)By H. Barbara Weinberg

- The Flag Paintings of Childe HassamOur PickBy Ilene Susan Fort