Summary of Reginald Marsh

Marsh was a keen observer of people and his exuberant, documentary style paintings are unique in their focus on crowds rather than individuals. Painting in the 1930s and 40s, Marsh portrayed a city undergoing radical social and economic change through the Depression, the altering role of women in society, and the onset of the Second World War. An urban realist, he was fascinated with populist activities including the amusements of Coney Island, burlesque shows, and dance halls, Marsh chronicled the daily lives of working class New Yorkers, often representing the seedier side of the entertainments they enjoyed. Although stylistically modern, Marsh can be seen as the New York equivalent of artists and caricaturists such as William Hogarth (eighteenth-century London) and Honore Daumier (nineteenth-century Paris), painting what he saw but also offering elements of social commentary and occasional satire.

Accomplishments

- Through complex, multi-figure compositions and bright colors Marsh captured the energy and pace of New York. His work often lacked a single visual focus and this, in conjunction with his choppy brushwork and asymmetry, does not allow the eye to settle at any one point, creating a sense of restlessness and continual movement in his paintings which is in direct contrast with other Regionalist artists.

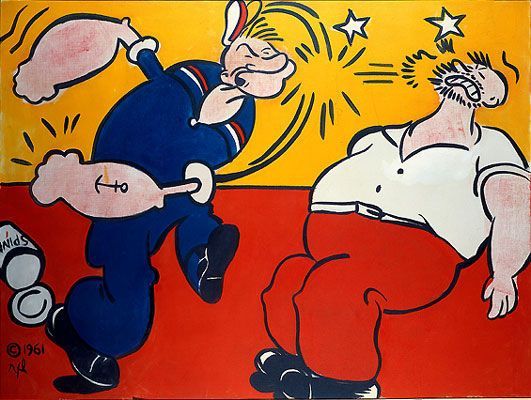

- The depiction of posters and advertising play a key role in many of Marsh's works focusing attention on the proliferation of the medium and contrasting its garish appearance, products, and promises with the everyday lives of those who consumed it. In faithfully reproducing this imagery and using it as a social commentary, Marsh can be seen as a forerunner of the Pop Art movement that emerged in the late 1950s.

- Many of Marsh's works display a separation and contrast between the sexes and there is often an element of voyeurism - men are shown in the background watching women perform in burlesque halls, but also on the street. The artist, however, seems to approach the subject of exploitation and power differential between the sexes with a degree of sympathy. The women that Marsh depicted were never diminutive but form a compelling focus for the viewer (as well as for the voyeurs).

- There is a strong sense of underlying sexuality in much of the artist's work. Marsh often portrayed the naked and scantily-clothed bodies of female performers or the swimsuit clad crowds on Coney Island. In utilizing this imagery Marsh highlighted the contrast between the respectable nudes of Renaissance and Baroque art and the more tawdry use of nudity in a burlesque context or in the exhibitionism associated with certain leisure pursuits.

The Life of Reginald Marsh

In works like Sorting the Mail (1936), as exhibited in the Ariel Rios Federal Building, Washington, D.C., Marsh highlighted a powerful, and also difficult, time in America.

Important Art by Reginald Marsh

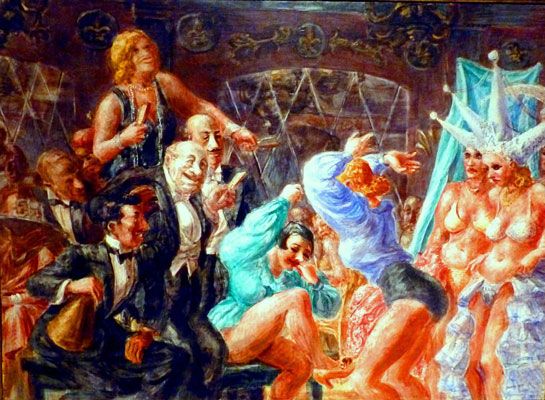

Texas Guinan and Her Gang

This is one of many paintings that Marsh created of the burlesque shows that were popular in New York during the 1930s, particularly as they often provided a place to purchase alcoholic drinks during prohibition. As with most of his pictures, Marsh portrays real people in it. The woman on the left of the image is Texas Guinan, a well-known silent movie star and live performer, who ran multiple burlesque clubs which were frequented by famous figures including Al Jolson, Gloria Swanson, and New York City mayor Jimmy Walker.

The women in the image are curvy with long legs and this style of depiction is seen throughout Marsh's work. The representation of Guinan as a strong and controlling figure full of energy rising above the leering faces of the men is contrasted with the world-weary expressions and states of undress of the performers to the right of the painting. This distinction is further enhanced by the bright colors of the performers' clothing and the effect of the stage lights in focusing attention onto the right of the canvas. The monochrome of the men's evening dress merges their figures into an indistinct mass on the left.

This juxtaposition between power and sexualization in the portrayal of women in Marsh's work has led to debate about his motives. Whilst author Marilyn Cohen argues that Marsh presents women as strong and purposeful and men as less imposing voyeurs, art historian, Erika Doss has suggested the opposite. Doss notes that Marsh's portrayals "...not only denigrated the lower-class women who worked in burlesque but helped to defuse the potentially threatening social and political ambitions of all modern American women".

Tempera on canvas - Collection of Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, New York

Bread Line - No One Has Starved

This etching, produced at the height of the Depression, shows a line of men waiting for governmental hand-outs of food. The bread line was a common theme in 1930s Social Realism as it demonstrated the tangible effects of the Depression on the working classes. Comparative examples can be seen in Iver Rose's Breadline (1935) and Margaret Bourke-White's iconic photograph, The Flood Leaves its Victims on the Bread Line (1937) which shows African American men and women queuing for food in front of a billboard that proclaims that America has the "world's highest standard of living". More recently the theme was revisited by sculptor George Segal in Depression Bread Line (1991).

The title of this piece is part of a quote taken from President Hoover, who running for reelection in 1932 stated that the American economy was fundamentally sound and that "No one has starved". Rather than seeking to depict individual representations of poverty, Marsh uses the line of similarly dressed men to present a collective image of the effects of the Depression. The line extends beyond the confines of the etching without suggesting a beginning or end and this, alongside the lack of space above and below the figures, alludes to their social and economic immobility.

Marsh briefly engaged with ideas associated with Communism, attending a few classes and contributing illustrations for New Masses, a magazine affiliated with the movement, the title of the piece, therefore, can be seen as a social commentary. The fact, however, that many of the men are attempting to pick the pockets of those in front of them in the line also implies an element of gentle satire to the work. This dichotomy is furthered by the parallels that can be drawn between the image and classical friezes. This can be seen as either a glorification of the average man by presenting them in a classical style or the satirical comparison of the out-of-work poor with the heroes of classical myth.

Etching on paper - Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York

Smoko, the Human Volcano

Marsh painted many scenes of people gathered at Coney Island, in this instance, side-show performers at the venue's carnival and amusement park. Marsh first visited Coney Island as an illustrator for Vanity Fair where he found inspiration in the large crowds of New Yorkers escaping from the city on hot days. He continued to make regular sketching trips and produced many paintings of the subjects he found there. Around the time he created this canvas he wrote to his wife Felicia, who was in Vermont, that "The wind was fresh and strong blowing great whitecaps in on the seas-the sea a rich blue-The crowd as thick as I've ever seen, much to my delight. The noise of the beach could be heard for miles and there was scarce room on the sand to sit down".

The painting is presented from the perspective of a member of the crowd and Marsh uses an elaborate background of oversized posters to frame the performers in the foreground and this is one of his reoccurring compositional elements. The final image was produced from both photographs and sketches and these demonstrate that Marsh reproduced the signs, along with the appearance and dress of the performers, faithfully. This documentary style of painting ties Marsh's work to a very specific period in time and this is reinforced by his compositions, representational style, and use of color which reflect the energy and alienation generated by a growth in advertising and commercialization.

Egg tempera on masonite - Collection of Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection on loan at the Museo Thyssen, Madrid, Spain

Coney Island

Here Marsh captures a crowd on the beach at Coney Island. In the foreground a provocatively posed woman attempts to capture the attention of a young man who seems oblivious to her actions and instead looks down at a sleeping man by his feet. In the background, barely visible through the throng of people, are attractions including a roller coaster and carousel. The two characters in the foreground frame the canvas and draw the eye into the crowd, the real focus of the piece. The limited color palette, overlapping limbs, and wide variety of poses makes it difficult for the viewer to pick out individuals within the jumble of bodies. This type of complex composition, with a flattened perspective was a hallmark of many of the artist's works. The figures on display are robust and the forms, both male and female, are energetic in their rendering with a sense of unfettered sexuality pervading the piece, suggesting both enjoyment and an element of the disreputable. The widespread use of yellows throughout the painting represents warmth and sunlight with the occasional red highlight pulling the focus towards the entwined bodies.

Whilst many artists of the 1930s focused on the hardships of the period, Marsh's work celebrates the cult of leisure that emerged in the same period, emphasizing the perseverance of New Yorkers to find what little happiness they could in difficult times. Cultural historian, Morris Dickstein supports this when he states, "Marsh's innumerable images of burlesque, of Coney Island, and of robust street life show us how much more was at stake in Depression-era pastimes than mere escapism...To Depression-era audiences, such diversions represented not simply escape but freedom, mobility, and gratification at a time when they felt hemmed in by grievous economic troubles and limited horizons".

Egg tempera on panel - Collection of Syracuse University Art Collection, Syracuse, New York

Down at Jimmy Kelly's

Jimmy Kelly's was an infamous bar in New York's Chinatown district and here Marsh portrays one of the strippers at work. It has been suggested that the seated man with a cigarette is a depiction of Marsh's friend, Lloyd Goodrich, a curator who would eventually serve as director of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The male audience are animated in their enjoyment of the entertainment and their leering and focused expressions contrast starkly with the appearance of the workers - the bored waiter in the background and the mask-like appearance of the dancer. Heavily made-up and naked apart from her shoes she seems entirely disengaged from her environment and the audience and instead gazes directly towards the viewer. The painting highlights the perspective of the dancer, portraying her in a sympathetic manner that seems to emphasize that she is simply going through the motions of her job, probably out of financial necessity. This lack of enthusiasm does not impinge on the audience who are viewing her merely as a sexual object.

Egg tempera on panel - Collection of Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia

Twenty Cent Movie

Twenty Cent Movie depicts the Lyric Theatre, covered in advertising and with a crowd outside, members of the working classes who frequented cinemas for the escapism that movies offered. Marsh was drawn to the cinema and often utilized cinematic imagery within his paintings, playing into the stereotypical themes and characters of 1930s films. Here he combines the make-believe world of cinema with that of the people who frequent it, drawing parallels between the images of movie stars displayed on the billboards and the confident self-presentation of the viewers who imitate them in dress and pose. The curve of the entrance to the cinema forms a proscenium arch at the top of the canvas and Marsh represents his figures acting out their lives with the street becoming the stage and the brightly colored advertising, the scenic backdrop.

Many of the posters on display on the front of the building suggest themes of sexual activity including 'Emotions Stripped Bare', 'Joys of the Flesh', and 'Dangerous Curves' all of which were real movies of the period. This theme is echoed in the partially clad statues in the foyer of the theater and the division between women on the left of the image and men on the right. Unlike many of Marsh's other images the figures are all full clothed and consequently the sexually charged nudity of other paintings is replaced by written rather than physical sexual content.

The use of sex as an advertising technique does, however, mirror the transactional nature of nudity and sex within the burlesque clubs that Marsh portrayed with such frequency.

Egg tempera on composition board - Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York

Untitled (Bowery Street)

This photograph depicts a scene in the Bowery part of New York City. Men in coats and hats walk down the sidewalk while to the left a parked car is just visible. On the right are shops with signs including an advertisement for a ten cent shave at a barber shop and the entrance to the Owl Hotel. Marsh was fascinated by advertising and replicated it in many of his paintings. This photograph may have helped to inspire Tattoo and Haircut (1932), which features similar signs.

Marsh became an avid photographer during the 1930s, utilizing the medium as both an independent way of documenting what he saw and as a method to rapidly capture subjects for future paintings. He often meticulously combined figures and groups from different photographs onto the same canvas to create the complex compositions for which he was known. His photos, particularly those of Coney Island, still feel fresh today and he excelled at capturing movement and taking images from new and unusual angles.

Gelatin silver print - Collection of Whitney Museum of Art, New York, New York

Biography of Reginald Marsh

Childhood and Education

Reginald Marsh was born into a wealthy American family. His parents were both artists, father, Fred Dana Marsh was known for his paintings and murals of society themes, whilst his mother, Alice Randall, focused on watercolor works. After spending the first two years of his life in Paris, the family returned to America, settling in an artists' colony in Nutley, New Jersey. The artist's formative years were spent surrounded by people who fostered his interest in art and the medium provided an outlet and form of expression for Marsh who was a shy and socially awkward child. In 1914, at the age of 16, Marsh moved with his family to New Rochelle, New York where shortly after he was sent away for his education first to Riverview Military Academy in Poughkeepsie and then to Lawrenceville Preparatory School in New Jersey.

Early Training

Marsh's formal artistic training began at Yale University in 1916. It was here that he became an illustrator and eventually the art director of the college publication the Yale Record. During this time, he often travelled to New York City to capture scenes of life for the magazine. After graduation he moved to the city, gaining employment at the Daily News as a staff artist and, later, as a cartoonist for The New Yorker when it began publishing in 1925. The observations he made for these outlets helped to shape the themes of his later paintings.

During this time, Marsh also furthered his artistic study, briefly attending the Art Students League in 1922 where he was influenced by his teacher Kenneth Hayes Miller. It was here that he met and, a year later married, his classmate Betty Burroughs who also came from an artistic family. Betty's father Bryson Burroughs, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, provided Marsh with exposure to important people in the New York art scene including Charles Burchfield and Edward Hopper.

Although Marsh initially considered painting "a laborious way to make a bad drawing" he was inspired to adopt the medium by a trip he and Betty took to Europe in 1925. While there, he was heavily influenced by Renaissance, Baroque, and Romantic artists. According to art historian and curator, Barbara Haskell, "he understood at once that the densely packed, agitated canvases of Baroque and Neo-Baroque artists contained clues to how he could impose order on New York's fast-paced, compressed, disjunctive stimuli without draining them of their lusty abundance and vitality".

Mature Period

In 1928 Marsh settled into a studio on Fourteenth Street where he worked among a community of artists including Isabel Bishop, Kenneth Hayes Miller, and Raphael Soyer, who focused on portraying the daily lives of New Yorkers. This group became known as the Fourteenth Street School. Whilst the artist began to develop his unique style, he also suffered a range of personal bereavements and issues, between 1927 and 1929 he lost his mother, brother, and grandfather (whose estate allowed him lifelong financial security). In 1932, he divorced his wife after she gave birth to a child that he realized he could not have fathered after discovering he was sterile. Six months later he married the 21 year old painter Felicia Meyer.

Despite these adversities, Marsh's career began to gain momentum and in 1929, he returned to the Art Students League to study with Thomas Hart Benton, with whom he became good friends. Benton introduced Marsh to tempera paint of which he said, "It opened up a new world to me". In addition, this association led to a connection with the Regionalism art movement. Whilst Marsh's depictions of city life distinguished him from Benton and most of the other Regionalist artists such as Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry who focused on rural scenes, his ability to capture the uniquely 'American' experience of urban life linked to the ethos of the movement.

In his paintings, Marsh portrayed people frequenting burlesque shows, cinemas, dance halls, and other attractions on Coney Island, as well as the struggling men and women on the streets of New York City's Bowery neighborhood. Whilst usually adopting the role of observer at these venues, on one occasion in 1936, the normally reserved Marsh was persuaded to join in a mock ceremony on the stage of the Oriental Theatre where he helped to present famous dancer Gypsy Rose Lee with an honorary 'Doctor of Strip Teasing' degree. When the push by authorities to close burlesque shows became serious and many owners became uncomfortable with allowing cameras or people to draw during shows, Marsh used a miniature notebook of only about four inches square hidden in his pocket to be able to continue making sketches of the crowds and performers.

Marsh also acknowledged the power of his art to help him combat his shyness when he stated that, "when I feel neglected at a party, I reach for my sketchbook, and soon everyone is gathered around, watching me". The work he produced in this period contributed to his selection for two federal government commissions as part of the Works Progress Administration, a mural in the Federal Building in Washington D.C. in 1936 and a sixteen panel design for the U.S. Custom House in New York in 1937 for which he depicted scenes of ships traveling to and arriving in the New York City harbor.

In addition to sketching, the camera proved an effective vehicle for Marsh to observe the world around him and he created many photographs throughout his career, particularly after the purchase of a Leica 35-mm camera in 1938. Whilst he was initially skeptical of what he described as the "fake realism" of the camera, he quickly changed his mind when he realized its potential noting that "this photography is the maddest activity I have ever taken up. I am planning many new subjects with the camera's aid".

Late Period

Marsh's paintings documented an important period in United States history, including the years of the Depression. His paintings were consequently bought by museums but did not, until years after his death, appeal to most private collectors. Aware of this, Marsh reasoned that his subject matter was too confrontational for the general public, but that this might change with time. He stated, "Wait awhile. Wait a generation or two - wait until my people look old-fashioned. When they look like people you never knew, almost like people who never lived....They'll just be strange, quaint people of somebody else's world. Then my pictures will sell. Then people will be glad to hang them on their walls. They'll boast about 'em then".

In addition to trying to understand the lack of interest by collectors, Marsh also had to defend himself from critical attacks most notably by artist Stuart Davis who after Time magazine's praise of Regionalism in 1934 publicly called the artists involved with the movement 'fascists' and accused Marsh directly of the sin of painting for fun. Marsh responded that he had nothing to apologize for and supporting his approach to realism stated, "Well, what should we do...be ashamed for being what we are....Whatever you say, there is a tradition to be proud of."

After the Second World War Marsh continued to paint in the style he had developed during the 1920s and 30s, in the post-war climate his style seemed dated and he was reluctant to embrace changes in the art world. Referencing what he felt was a disturbing shift away from realism to abstraction he stated, "Everything I've loved is disappearing. They've torn down the El; the burlesque is gone. I hardly recognized Coney Island anymore. All the things of the old days were so much better to draw. The Art Museums of our country...are rapidly and tragically snuffing out the representation of form and life, in favor of pictures that picture nothing. The Connoisseurs who hate pictures that contain Things, Men, Women, Sex, Cows, Skies, Trees, Ships, Shoes, and Subways are pleased with their point of view and say that at least there is now ART - High and Pure and Sterile - no Sex, no Drinks, no Muscles". Marsh also fell out of favor with some critics who drew parallels between his work and Soviet and Fascist propaganda. This shift in perception affected Marsh deeply and his work began to change as he turned inwards creating images less focused on realism.

During the 1940s Marsh returned to the Art Students League as a teacher and continued to work in illustration, creating images for magazines including Life, Fortune, and Esquire. He did not, however, live to see the resurgence of his art which happened decades later. Marsh felt the decline in appreciation of his work keenly and this is evident in the months before his death, when, upon receipt of the Academy of Arts and Letters' Gold Medal for Graphic Art, he simply stated by way of acknowledgement that, "I am not a man of this century".

The Legacy of Reginald Marsh

Reginald Marsh's biggest impact can be seen terms of social history, providing an unique insight into the daily life of 1930s New Yorkers. His subject matter offered a different approach to those of many of the Social Realist and Regionalist artists who chose to focus on the difficulties associated with the Great Depression years, whilst Marsh's depictions demonstrate the ability of humans to find some semblance of enjoyment and happiness in what was an otherwise oppressive period in American history. His pieces are not just documentary but capture the spirit of the time, conveying energy and change.

Marsh's ability to elevate scenes of popular culture, marketing, and advertising to the status of fine art can be viewed as laying the foundations for the Pop Art movement and Marsh had a strong thematic influence on Roy Lichtenstein who was one his pupils at the Art Students League. According to Barbara Haskell, "Decades before the Pop artists turned their attention to advertising and tabloid headlines, Marsh understood these art forms as modern-day folktales. By situating their visual messages within the tumultuous jumble of unrelated, fragmentary images that constitute the modern urban landscape, he conveyed the ambiguity, fragmentation, and disorienting flux of the world in which we live and attempt to establish meaningful human relationships".

Influences and Connections

-

![Charles Burchfield]() Charles Burchfield

Charles Burchfield -

![Eugène Delacroix]() Eugène Delacroix

Eugène Delacroix -

![Edward Hopper]() Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper -

![Michelangelo]() Michelangelo

Michelangelo - Isabel Bishop

![Lloyd Goodrich]() Lloyd Goodrich

Lloyd Goodrich- Alan Burroughs

- Bryson Burroughs

-

![Charles Burchfield]() Charles Burchfield

Charles Burchfield -

![Edward Hopper]() Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper -

![Ben Shahn]() Ben Shahn

Ben Shahn - Isabel Bishop

- Edward Lanning

![Lloyd Goodrich]() Lloyd Goodrich

Lloyd Goodrich- Alan Burroughs