Summary of Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse is widely regarded as the greatest colorist of the 20th century and as a rival to Pablo Picasso in the importance of his innovations. He emerged as a Post-Impressionist, and first achieved prominence as the leader of the French movement Fauvism. Although interested in Cubism, he rejected it, and instead sought to use color as the foundation for expressive, decorative, and often monumental paintings. As he once controversially wrote, he sought to create an art that would be "a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair." Still life and the nude remained favorite subjects throughout his career; North Africa was also an important inspiration, and, towards the end of his life, he made an important contribution to collage with a series of works using cut-out shapes of color. He is also highly regarded as a sculptor.

Accomplishments

- Matisse used pure colors and the white of exposed canvas to create a light-filled atmosphere in his Fauve paintings. Rather than using modeling or shading to lend volume and structure to his pictures, Matisse used contrasting areas of pure, unmodulated color. These ideas continued to be important to him throughout his career.

- His art was important in endorsing the value of decoration in modern art. However, although he is popularly regarded as a painter devoted to pleasure and contentment, his use of color and pattern is often deliberately disorientating and unsettling.

- Matisse was heavily influenced by art from other cultures. Having seen several exhibitions of Asian art, and having traveled to North Africa, he incorporated some of the decorative qualities of Islamic art, the angularity of African sculpture, and the flatness of Japanese prints into his own style.

- Matisse once declared that he wanted his art to be one "of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter," and this aspiration was an important influence on some, such as Clement Greenberg, who looked to art to provide shelter from the disorientation of the modern world.

- The human figure was central to Matisse's work both in sculpture and painting. Its importance for his Fauvist work reflects his feeling that the subject had been neglected in Impressionism, and it continued to be important to him. At times he fragmented the figure harshly, at other times he treated it almost as a curvilinear, decorative element. Some of his work reflects the mood and personality of his models, but more often he used them merely as vehicles for his own feelings, reducing them to ciphers in his monumental designs.

The Life of Henri Matisse

Matisse meticulously experimented with art, trying and retrying ideas saying: "I have always tried to hide my efforts and wished my works to have a light joyousness of springtime which never lets anyone suspect the labors it has cost me."

Important Art by Henri Matisse

Luxe, Calme, et Volupte

The title of this painting is taken from the refrain of Charles Baudelaire's poem, Invitation to a Voyage (1857), in which a man invites his lover to travel with him to paradise. The landscape is likely based on the view from Paul Signac's house in Saint-Tropez, where Matisse was vacationing. Most of the women are nude (in the manner of a traditional classical idyll), but one woman - thought to represent the painter's wife - wears contemporary dress. This is Matisse's only major painting in the Neo-Impressionist mode, and its technique was inspired by the Pointillism of Paul Signac and Georges Seurat. He differs from the approach of those painters, however, in the way in which he outlines figures to give them emphasis.

Oil on canvas - Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

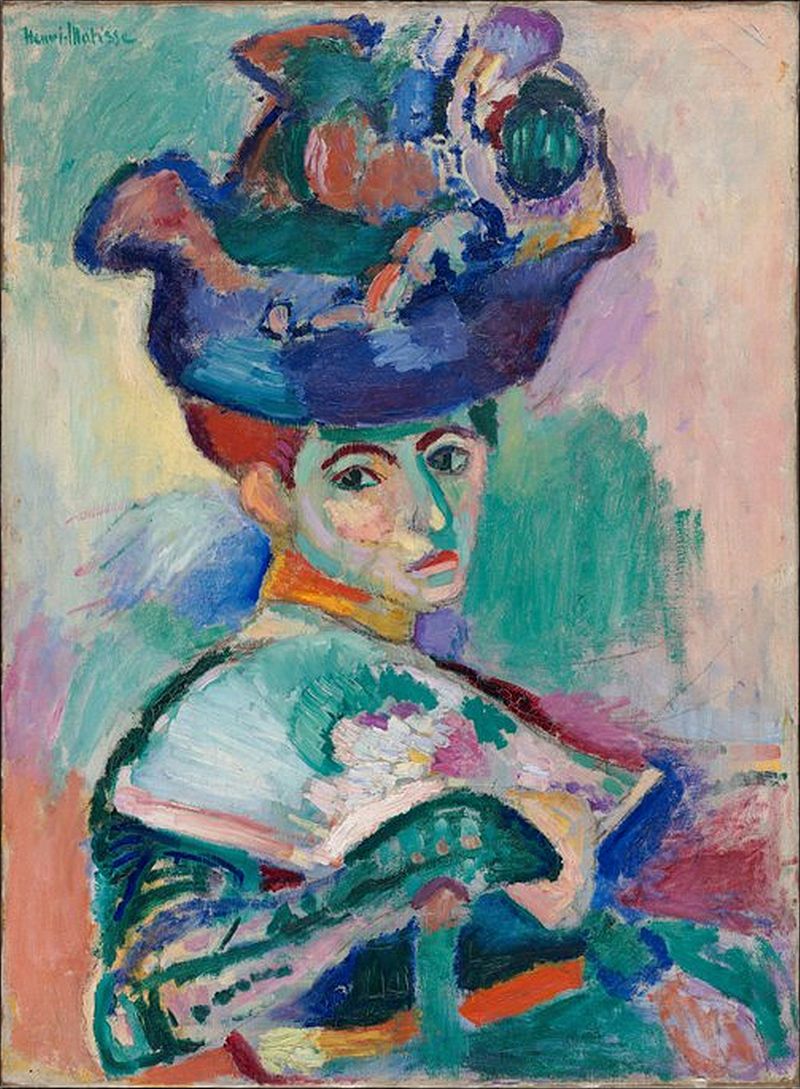

The Woman with a Hat

Matisse attacked conventional portraiture with this image of his wife. Amelie's pose and dress are typical for the day, but Matisse roughly applied brilliant color across her face, hat, dress, and even the background. This shocked his contemporaries when he sent the picture to the 1905 Salon d'Automne. Leo Stein called it, "the nastiest smear of paint I had ever seen," yet he and Gertrude bought it for the importance they knew it would have to modern painting.

Oil on canvas - The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Joy of Life (Le Bonheur de Vivre)

During his Fauve years Matisse often painted landscapes in the south of France during the summer and worked up ideas developed there into larger compositions upon his return to Paris. Joy of Life, the second of his important imaginary compositions, is typical of these. He used a landscape he had painted in Collioure to provide the setting for the idyll, but it is also influenced by ideas drawn from Watteau, Poussin, Japanese woodcuts, Persian miniatures, and 19th-century Orientalist images of harems. The scene is made up of independent motifs arranged to form a complete composition. The massive painting and its shocking colors received mixed reviews at the Salon des Indépendants. Critics noted its new style -- broad fields of color and linear figures, a clear rejection of Paul Signac's celebrated Pointillism.

Oil on canvas - The Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania

Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra)

Matisse was working on a sculpture, Reclining Nude I, when he accidentally damaged the piece. Before repairing it, he painted it in blue against a background of palm fronds. The nude is hard and angular, both a tribute to Cézanne and to the sculpture Matisse saw in Algeria. She is also a deliberate response to nudes seen in the Paris Salon - ugly and hard rather than soft and pretty. This was the last Matisse painting bought by Leo and Gertrude Stein.

Oil on canvas - The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Cone Collection

The Back I

Although Matisse is known above all as a painter, sculpture was also important to him, and he was particularly inspired by Auguste Rodin, whom he visited in his studio in 1900. The Back I is the first of a series of four large relief sculptures that Matisse worked on between 1909 and 1931, all of which are significantly innovative. Conventionally, the background of a relief sculpture is regarded as a virtual plane, a kind of imaginary space that the viewer fills in with his own notions. But in The Back series, Matisse suggested that the backdrop was fashioned from the same heavy material as the figure itself. Throughout the series, the figure is progressively simplified and further identified with the background. The motif was possibly first inspired by a figure in a painting by Cézanne that Matisse owned.

Bronze - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Moroccans

Matisse planned this picture as early as 1913, and it recalls visits made to Morocco around this time. A figure sits on the right with a back to us, fruit lies in the left foreground, and a mosque rises in the background beyond a terrace. Matisse said that he occasionally used black in his pictures in order to simplify the composition, though here it undoubtedly also recalls the stark shadows produced by the strong sunshine in the region. Like Bathers by a River (1917), The Moroccans was significantly influenced by Picasso's Cubism, and some have even compared it to Picasso's Three Musicians (1921). Although it employs the same brilliant color as much of Matisse's work, its use of abstract motifs and rigid diagrammatic composition is unusual, and has attracted considerable speculation. Rather than use the scene as an opportunity for decoration, it is as if Matisse has tried to find the means to chart and map it.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Bathers by a River

Matisse regarded this picture as one of the most important in his career, and it is certainly one of his most puzzling. He worked on it at intervals over eight years, and it passed through a variety of transformations. The painting evolved out of a commission from Matisse's Russian patron, Sergei Shchuckin, for two decorative panels on the subjects of dance and music, and, initially, the scheme for the picture resembled the idyllic scenes he had previously depicted in paintings such as Joy of Life (1905-06). However, his transformations gradually turned it into more of a confrontation with Cubism, and it is for this reason that the picture has been the subject of intense scrutiny. Although Matisse rejected Cubism, he certainly felt challenged by it, and this picture - along with many he painted from 1913 to 1917 - seems to be influenced by the style, since it is very unlike his previous, more decorative work. It is far more concerned with faithful representation of the structure of the human figure, and its position in space. The painting might be compared to The Backs series (1909-31), which also preoccupied Matisse the years he was working on Bathers, since both address the problem of depicting a three-dimensional figure against a flat background.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

The Dance II

Albert Barnes, a doctor and art lover, commissioned Matisse in 1931 to paint a mural for the main hall of his gallery housing works by Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and others. Matisse created a maquette for the mural out of cut paper, which he could rearrange as he determined the composition. However, the finished work was too small for the space due to being given incorrect measurements. Rather than add a decorative border, Matisse decided to recompose the entire piece, resulting in a dynamic composition, in which bodies seem to leap across abstracted space of pink and blue fields.

Oil on canvas - Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania

Blue Nude II

Matisse completed a series of four blue nudes in 1952, each in his favorite pose of entwined legs and raised arm. Matisse had been making cut-outs for eleven years, but had not yet seriously attempted to portray the human figure. In preparation for these works, Matisse filled a notebook with studies. He then created a figure that is abstracted and simplified, a symbol for the nude, before incorporating the nude into his large-scale murals.

Gouache-painted paper cut-outs - Private Collection

Biography of Henri Matisse

Childhood

Henri-Emile-Benoit Matisse was born to middle-class parents Emile-Hippolyte-Henri Matisse, a grain and hardware merchant, and Anna Heloise Gerard. He grew up in Bohain-en-Vermandois and went to school at the College de Saint Quentin, before moving to Paris to study law. In 1889, he returned to Saint-Quentin as a law clerk, though he found the job tedious and complained of anxiety. Later that year he contracted appendicitis and spent several months at home recovering. During that time, at the age of 20, he discovered the welcome isolation and freedom of painting.

Early Training

Struck by his new passion, Matisse left for Paris again in 1891, this time to study art. He failed the entrance exams for the École des Beaux Arts, but unofficially joined the studio of French symbolist painter Gustave Moreau in 1892. Moreau told his students, "Colors must be thought, dreamed, imagined." This Symbolist attitude toward painting contributed to Matisse's expressive use of color. In 1894, Matisse unexpectedly had a daughter, Marguerite, with his lover, Caroline Joblaud. After finally being accepted to the École des Beaux Arts in 1895, he continued to study with Moreau until 1898. Many styles influenced the painter during these years, from the academic still lifes of Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin to the loose brushwork of the Impressionists.

In 1898, having ended his relationship with Caroline, Matisse married Amelie Parayre. Moreau died while the couple was abroad for their honeymoon, and Matisse struggled to find another teacher. He was also faced with the challenge of raising three children - he and his wife had two sons, Jean in 1899 and Pierre in 1900. Despite their financial struggles, Matisse began his lifelong collection of avant-garde art, purchasing Three Bathers (1879-82) by Paul Cézanne from the gallery of Ambroise Vollard. Influenced by the Post-Impressionists' use of color, and the writing of art critic Paul Signac, Matisse moved past his Impressionist exploration.

Mature Period

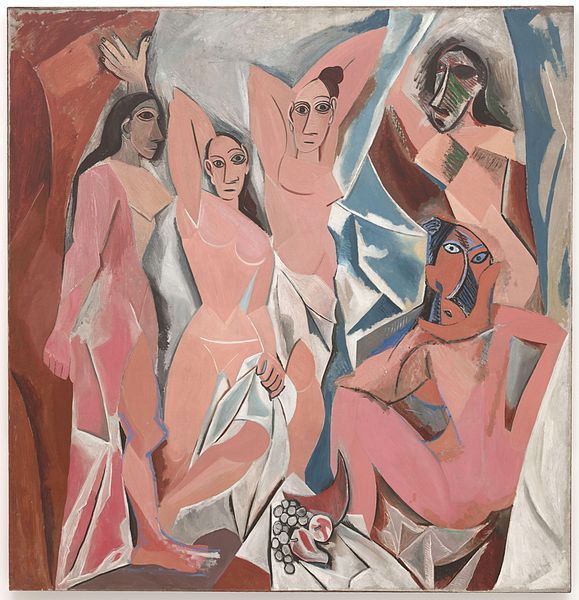

Matisse spent summer 1905 in Collioure, working with André Derain to create a new style of pure colors and bright light. The new style became known as Fauvism, after critic Louis Vauxcelles described the arrangement of works at the Salon d'Automne in 1905 - an important showcase for the new movement - as "Donatello among the wild beasts [fauves]." Matisse was soon known as the Fauvists' leader in the press, called "chief fauve" by Louis Vauxcelles and other critics. The Fauvist movement, though short-lived, forged one of modern art's two directions. In 1905, Matisse met Pablo Picasso at the studio of Gertrude Stein. The two artists began a lifelong friendship and rivalry, each artist representing a possible direction modern art could take after the death of Paul Cézanne. While Picasso deconstructed objects into Cubist planes, Matisse sought to construct an object's form through color.

By 1907, painters were no longer working in the Fauve style, not even Matisse. He moved on to create simplified forms against flat planes of color. His interest in sculpture intensified as well, especially North African work, probably due to his experiences on a 1906 trip to Algeria. He used sculpture to resolve pictorial problems, especially those relating to the figure. He also acquired the support to open an art school in 1908, teaching approximately eighty students over three years. And he gained patronage from collectors of avant-garde art, including the Russian collector Sergei Ivanovich Shchukin, who eventually owned dozens of his paintings.

From 1911 to 1916, Matisse focused on depicting the human figure in interior spaces decorated with Eastern rugs and souvenirs. While he was not drafted during World War I, the seriousness of world events affected his painting, muting his palette. Towards the end of the war, however, he returned to his bright colors, leading to his "Nice period" from 1917 to 1930. Many of these paintings make use of the white of the exposed canvas to suggest the bright light of southern France.

In 1930, Matisse went through a time of artistic crisis and transition. Dissatisfied with the conservative direction of his work, he traveled first to Tahiti, then to America three times in three years. He spent much less energy on easel painting, instead experimenting with book illustration, tapestry design, and glass engraving. In 1931, he was commissioned to create a mural for the Barnes Foundation in Pennsylvania, which he completed in 1933.

Late Years and Death

Matisse's separation from his wife in 1939, the arrival of World War II, and ill health, all added to Matisse's anxiety over the direction of his work. After major surgery in 1941, he was confined to a wheelchair. He turned to drawing and paper cut-outs, media that were physically more manageable and offered new potential for expression. Paper cut-outs symbolized for Matisse the synthesis of drawing and painting.

The paper cut-outs encouraged Matisse to simplify forms even further, distilling the object's "essential character" until it became a symbol of itself. He used the paper cut-out technique to design stained glass windows for the Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence, France, and as a medium in its own right in large-scale works. With the help of assistants, Matisse was able to continue working through his illness. On November 3, 1954, Matisse died of a heart attack.

The Legacy of Henri Matisse

Scholars in the 1950s described Matisse and Fauvism as a precursor of Abstract Expressionism and much of modern art. Several Abstract Expressionists trace their lineage to him, though for different reasons. Some, like Lee Krasner, are influenced by his various media; Matisse's paper cut-outs inspired her to cut up her own paintings and reassemble them. Color field painters, such as Mark Rothko and Kenneth Noland, were taken with his broad fields of bright color, as in the Red Studio (1911). Richard Diebenkorn, on the other hand, was more interested in how Matisse created the illusion of space and the spatial tension between his subject matter and the flat canvas. Others, like Robert Motherwell, did not show Matisse's influence directly in their artwork, but were influenced by his view of painting color and form. Matisse's art continues to beguile not only artists, but also collectors, who have bought his paintings for as much as $17 million. And as several recent and upcoming blockbuster exhibitions suggest, he continues to be a favorite of the public worldwide.

Influences and Connections

![Henri Bergson]() Henri Bergson

Henri Bergson![Albert Marquet]() Albert Marquet

Albert Marquet![Leo Stein]() Leo Stein

Leo Stein

-

![Clement Greenberg]() Clement Greenberg

Clement Greenberg -

![Alfred H. Barr, Jr.]() Alfred H. Barr, Jr.

Alfred H. Barr, Jr. ![Sergei Shchukin]() Sergei Shchukin

Sergei Shchukin

Useful Resources on Henri Matisse

- The Unknown MatisseOur PickBy Hilary Spurling

- Matisse the Master: A Life of Henri Matisse: The Conquest of Colour, 1909-1954By Hilary Spurling

- Matisse And Picasso: The Story Of Their Rivalry And FriendshipBy Jack Flam

- Matisse in the StudioBy Ellen McBreen and Helen Burnham

- In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and the Birth of Modernist ArtOur PickBy Sue Roe

- Henri Matisse (Critical Lives)By Kathryn Brown

- Matisse's "Notes of a Painter": Criticism, Theory, and Context, 1891-1908Our PickBy Roger Benjamin

- JazzBy Henri Matisse, Riva Castleman

- Matisse on ArtBy Henri Matisse, Jack Flam

- Matisse: The BooksOur PickBy Louise Rogers Lalaurie

- Henri Matisse: A RetrospectiveOur PickBy John Elderfield

- Matisse: A RetrospectiveBy Jack Flam

- Henri Matisse: The Cut-OutsOur PickBy Karl Buchberg, Nicholas Cullinan, and Jodi Hauptman

- Matisse in the Barnes Foundation: 3 Vol. SetOur PickBy Yve Alain-Bois

- MatisseOur PickBy Volkmar Essers

- Matisse and DecorationBy John Klein

- Matisse: From Color to ArchitectureOur PickBy Rene Percheron and Christian Brouder

- Matisse: PrintmakerBy Jean Fisher

- Matisse: His Art and His PublicBy Alfred Hamilton Barr Jr.

- Matisse: In Search of True PaintingOur PickBy Rebecca Rabinow and Dorthe Aagesen

- MatisseOur PickBy Pierre Schneider

- Inside Matisse: Understanding Henri MatisseBy Spatio Temprey

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI