Summary of Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch was a prolific yet perpetually troubled artist preoccupied with matters of human mortality such as chronic illness, sexual liberation, and religious aspiration. He expressed these obsessions through works of intense color, semi-abstraction, and mysterious subject matter. Following the great triumph of French Impressionism, Munch took up the more graphic, symbolist sensibility of the influential Paul Gauguin, and in turn became one of the most controversial and eventually renowned artists among a new generation of continental Expressionist and Symbolist painters. Munch came of age in the first decade of the 20th century, during the peak of the Art Nouveau movement and its characteristic focus on all things organic, evolutionary, and mysteriously instinctual. In keeping with these motifs, but moving decidedly away from their decorative applications, Munch came to treat the visible as though it were a window into a not fully formed, if not fundamentally disturbing, human psychology.

Accomplishments

- Edvard Munch grew up in a household periodically beset by life-threatening illnesses and the premature deaths of his mother and sister, all of which was explained by Munch's father, a Christian fundamentalist, as acts of divine punishment. This powerful matrix of chance tragic events and their fatalistic interpretation left a lifelong impression on the young artist, and contributed decisively to his eventual preoccupation with themes of anxiety, emotional suffering, and human vulnerability.

- Munch intended for his intense colors, semi-abstraction, and mysterious, often open-ended themes to function as symbols of universal significance. Thus his drawings, paintings, and prints take on the quality of psychological talismans: having originated in Munch's personal experiences, they nonetheless bear the power to express, and perhaps alleviate, any viewer's own emotional or psychological condition.

- The frequent preoccupation in Munch's work with sexual subject matter issues from both the artist's bohemian valuation of sex as a tool for emotional and physical liberation from social conformity as well as his contemporaries' fascination with sexual experience as a window onto the subliminal, sometimes darker facets of human psychology.

- In a sense similar to his near-contemporary, Vincent van Gogh, Munch strove to record a kind of marriage between the subject as observed in the world around him and his own psychological, emotional and/or spiritual perception.

The Life of Edvard Munch

Munch’s often confusing and depressing, if not downright disturbing, artworks no doubt developed out of his troubling and traumatic childhood experiences, and the resulting psychological anguish that plagued him throughout his life.

Important Art by Edvard Munch

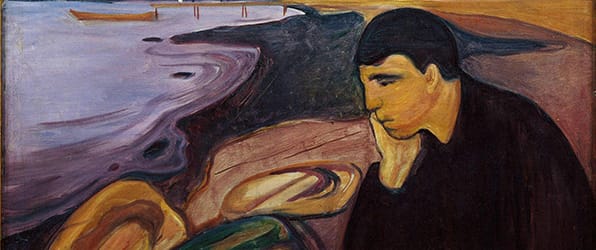

The Sick Child

The Sick Child is one of Munch's earliest works, considered by the artist "a breakthrough" for setting the tone for his early career in which death, loss, anxiety, madness, and the preoccupations of a troubled soul were his chief subject matter. Devoted to his deceased sister, Johanne Sophie, the painting depicts the bedridden fifteen-year-old with a grieving woman beside her, the latter probably a representation of Munch's mother who had preceded Sophie in death, also from tuberculosis, eleven years prior. The rough brushstrokes, scratched surface, and melancholic tones of this painting all reveal a highly personal memorial. The work was highly criticized for its "unfinished appearance" when first exhibited, but nonetheless championed by Munch's spiritual mentor, Hans Jæger, as a masterful achievement.

Oil on canvas - Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

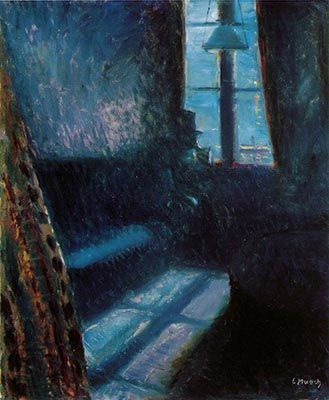

Night in St. Cloud

If the Sick Child is a loving tribute to Munch's favorite sister, Johanne Sophie, Night in St. Cloud is a far more complex and darker memorial to the artist's father who had died the previous year. Created not long after Munch's arrival in Paris, Night in St. Cloud reveals the immediate influence of Post-Impressionists Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec, whose many portraits of solitary figures or empty rooms inform this canvas. Munch's tribute to his father is composed of a darkened, seemingly hallowed room bathed in crepuscular light, indeed a space occupied only by shadows and stillness. The rendition is befitting of their tense relationship. In other paintings that focus on death, Munch made the subject physically present; however, in this instance, Munch's father's passing evokes only a sense of cool abandon. Notably, this work presages Pablo Picasso's Blue period.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, Oslo

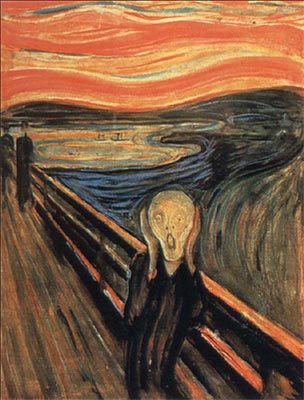

The Scream

The significance of Munch's The Scream within the annals of modern art cannot be overstated. It stands among an exclusive group, including Van Gogh's Starry Night (1889), Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), and Matisse's Red Studio (1911), comprising the quintessential works of modernist experiment and lasting innovation. The fluidity of Munch's lateral and vertical brushwork echoes the sky and clouds in Starry Night, yet one may also find the aesthetic elements of Fauvism, Expressionism, and perhaps even Surrealism arising from this same surface.

The setting of The Scream was suggested to the artist by a walk along a road overlooking the city of Oslo, apparently upon Munch's arrival at, or departure from, a mental hospital where his sister, Laura Catherine, had been interned. It is unknown whether the artist observed an actual person in anguish, but this seems unlikely; as Munch later recalled, "I was walking down the road with two friends when the sun set; suddenly, the sky turned as red as blood. I stopped and leaned against the fence ... shivering with fear. Then I heard the enormous, infinite scream of nature."

This is one of two painted versions of The Scream that Munch rendered around the turn of the 20th century; the other (c. 1910) is currently in the collections of the Munch Museum, Oslo. In addition to these painted versions, there is a version in pastel and a lithograph.

Oil, tempera, and pastel on cardboard - The National Gallery, Oslo

Madonna

Contemporary with The Scream, Munch's Madonna is rendered with softer brushstrokes and comparatively subdued pigments. Munch depicts the Virgin Mary in a manner that defies all preceding "historical" representations - from Renaissance-era Naturalism to 19th-century Realism - of the chaste mother of Jesus Christ. With a sense of modesty conveyed only by her closed eyes, the nude appears to be in the act of lovemaking, her body subtly contorting and bending towards a nondescript light. Indeed, Munch's Madonna may very well be a modernist, if irreverent depiction of the Immaculate Conception. The red halo upon the Madonna's head, as opposed to the customary white or golden ring, indicates a ruling passion befitting Baroque-era renditions of the subject, minus any measure of religious discretion. While the artist himself never fully succumbed to his father's religious fervor and teachings, this work clearly suggests Munch's constant wrangling over the exact nature of his own spirituality.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, Oslo

Puberty

Agony, anxiety and loss are constant themes throughout Munch's oeuvre, yet perhaps nowhere do they come together as powerfully as in Munch's Puberty, a portrait of adolescence and isolation. The lone and guarded female figure symbolizes a state of sexual depression and frustration - both of which plagued the artist himself throughout his life while the girl, although apparently shy (to judge by her posture), indicates quite the opposite by way of her frank stare. The looming shadow behind the figure hints at the birth of an ominous and sentient creature, perhaps one haunting her room, if indeed it is not her own dawning persona. The aesthetic qualities of Post-Impressionism are still very much present in Munch's work at this time, but what sets his work apart is the powerful element of symbolism. Munch is painting not necessarily what he sees, but what he feels in front of him. Munch usually painted, in fact, from imagination rather than from life, but here the uncharacteristic detailing of the girl's body - in particular the collar bone is considered by many evidence that, at least in this instance, Munch resorted to the use of a live model.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery, Oslo

Spring Ploughing

In the years following Munch's hospital stay the artist removed himself from the lifestyle of carousing and heavy drinking and devoted his days to his art and to the countryside of his homeland. While at one time the artist referred to his paintings as "my children," by this time he began referring to them as "my children with nature." This new-found inspiration, in the form of farm hands, animals, and the Norwegian landscape, took Munch's art in an entirely new direction, one celebrating life and work, rather than anxiety and loss. In Spring Ploughing, one can see the inspiration Munch took from the much younger Franz Marc - whose Expressionist paintings were originally inspired by Munch - who had a penchant for painting animals in their natural surroundings. Munch's period of creating truly original Symbolist-cum-Expressionist works had since passed, indicated by similar works of this time and their innocent subject matter. Nevertheless, the maturity of this painting's brushwork and palette clearly demonstrate the hand of a master.

Oil on canvas - Munch Museum, Oslo

Biography of Edvard Munch

Childhood

Edvard Munch was born in 1863 in a rustic farmhouse in the village of Adalsbruk, located in Loten, Norway. His father, Christian Munch, was a practicing physician, married to Laura Catherine Bjolstad. The family, including sisters Johanne Sophie, Laura Catherine, Inger Marie, and brother Peter, relocated to Oslo in 1864, following Christian's appointment as medical officer at Akershus Fortress, a military area which at the time was in use as a prison. Munch's mother died of tuberculosis in 1868, the same year Inger Marie was born. Within a decade, Munch's favorite sister, Sophie, just one year his senior and a gifted young artist, also died of tuberculosis. Munch's father, a fundamentalist Christian, thereafter experienced fits of depression and anger as well as quasi-spiritual visions in which he interpreted the family's illnesses as punishment of divine origin.

Due largely to Christian's medical career with the military, the family moved frequently and lived in relative poverty. Christian would often read to his children the ghost stories of Edgar Allan Poe, as well as lessons in history and religion, instilling in young Munch a general sense of anxiety about (and morbid fascination with) death. Adding to this, Munch's frail immune system was little match for the harsh Scandinavian winters and frequent illness kept him out of school for months on end. To pass the time, Munch took up drawing and watercolor painting.

Art became a steady preoccupation for Munch during his teen years. At thirteen, he was exposed to the works of the fledgling Norwegian Art Association and was particularly inspired by the group's landscape paintings. In the course of copying these works he taught himself the techniques of oil painting.

Early Training

In the 1880s, seeking a bohemian lifestyle, Munch discovered the writings of the anarchist philosopher, Hans Jæger, head of a group called the "Kristiania-Boheme" (as a central principle of a larger anti-bourgeois agenda, the group advocated liberal sexual behavior, or "free love," and the abolition of marriage). Munch and Jæger formed a close friendship, and Jæger encouraged the artist to draw more from personal experience in his work. The Sick Child (1885-86), a somber composition that served as a memorial to Munch's deceased sister, Sophie, speaks to Jæger's profound influence on Munch at this juncture. When the painting was exhibited as A Study in Kristiania in 1886, it was attacked by critics as well as Munch's own colleagues for its overtly unconventional qualities, such as its scratched paint surface and the work's generally unfinished appearance.

In 1889, Munch traveled to Paris on a state fellowship to study in the studio of Leon Bonnat. His painting Morning (1884) was included in the Norwegian pavilion of the Exposition Universelle of that same year. Munch began to draw in Paris after Impressionists, such as Manet, and the Post-Impressionists Gauguin, van Gogh, and Toulouse-Lautrec, whose sometimes airy compositions differed dramatically from Munch's frequent themes of death and personal loss. That same year Munch's father passed away, a traumatic event that instilled in the artist a new-found interest in spirituality and symbolism. This is evidenced in the brooding painting of an empty room, Night in St. Cloud (1890), which served as a memorial to Christian Munch.

Mature Period

In 1892, the Union of Berlin Artists invited Munch to be the subject of the union's first solo exhibition. The works on view created much controversy due to their radical color and brooding subject matter and the exhibition was prematurely closed. Munch capitalized on the residual publicity and his career flourished as a result. A year later he exhibited a group of six love-themed paintings in Berlin that would eventually evolve into the larger, renowned series Frieze of Life - A Poem about Life, Love, and Death (1893).

The Frieze series and related works produced by Munch in the 1890s are among the most artistically significant and popularly renowned of his entire career. Munch now created in quick succession his signature paintings The Scream (1893), Love and Pain (1893-94), Ashes (1894), Madonna (1894-95), and Puberty (1895). While these works comprise just a portion of Munch's finest outpouring, they all evoke his characteristically profound, poetic melancholy grounded in themes of isolation, death, and the loss of innocence. In the late 1890s Munch also took up an interest in photography, although he never considered the medium the artistic equal of painting or printmaking.

Late Period

In 1908, following his stay in Berlin and subsequent return to Paris, Munch suffered a nervous breakdown. A bohemian life of excessive drinking and brawling and the pain and anxiety caused by the loss of his sister and father had taken their toll. Munch was admitted to a hospital in Copenhagen, where for eight months he was subject to a strict dietary and "electrification" regimen. While hospitalized, Munch created the lithographic series, Alpha and Omega (1908), depicting the artist's relationships with various friends and enemies.

Munch was released from the hospital the following year and, as advised by his doctor, he immediately returned to Norway to lead a life of quiet isolation. Subsequently, Munch derived inspiration from the Norwegian landscape and the daily activities of farmers and laborers. Reflecting a newly optimistic perspective, Munch's work from this period employed a lighter palette (including white or negative space, a quality virtually absent from former works), loose brushstrokes, and themes revolving around life, work and recreation on the farm. Among representative works of this period are The Sun (1912), Spring Ploughing (1916), and Bathing Man (1918).

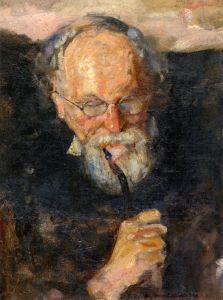

Munch continued drawing from his daily life and personal experience, now shunning overt themes of loss and death. An exception was Munch's focus on his own mortality, as is reflected in several somber self-portraits of the 1930s and 40s. He additionally produced much drawing and painting of landscape.

In 1940, Norway was invaded by the Nazis; subsequently, many of Munch's paintings were deemed "degenerate" by Hitler and removed from German museums. Of eighty-two works confiscated during the war, seventy-one (including The Scream) were eventually rescued by Norwegian collectors and benefactors and returned to Munch's native Norway.

At the age of 80, his vision having failed him intermittently since his early 70s, and suffering an extended illness brought on by an explosion of a neighborhood munitions factory, Munch died in the town of Ekely, just outside of Oslo.

The Legacy of Edvard Munch

Munch had a profound effect on subsequent painters in Europe and the United States, even as his particular style dated quickly after the First World War. Pioneering German Expressionist painters such as Kirchner, Kandinsky, Beckmann, and others concerned with expressing individual psychology through intense color and semi-abstraction found considerable inspiration in Munch's melancholy yet strident canvases. Munch's somber, resonant color, as well as his rendering of the human figure in semi-abstract tonalities, would prove enduring expressive and stylistic hallmarks of Symbolism, Expressionism, Fauvism, and even Surrealism. One sees Munch's extended influence even in the work of a later painter such as Francis Bacon, whose portraits reflect the sitter's psychological turmoil that is manifested in skewed facial and bodily features.

On his death in 1944, it was learned that Munch had bequeathed his remaining work to the city of Oslo. Numbering about 1,100 paintings, 4,500 drawings, and 18,000 prints, the collection was provided its own museum in 1963, where it serves as a testament to Munch's lasting legacy.

Influences and Connections

-

![Franz Marc]() Franz Marc

Franz Marc ![Hans Jaeger]() Hans Jaeger

Hans Jaeger![Christian Krohg]() Christian Krohg

Christian Krohg

-

![Franz Marc]() Franz Marc

Franz Marc -

![Robert Rosenblum]() Robert Rosenblum

Robert Rosenblum ![August Strindberg]() August Strindberg

August Strindberg![Max Linde]() Max Linde

Max Linde