Summary of Rachel Whiteread

Before Rachel Whiteread, no artist had ever found a way of making the air that surrounds an object the subject of their work. Rather than pouring a liquid, such as molten metal, plastic, rubber, or fiberglass into a mold to make a replica of a regular, pre-existing work, she made a plaster cast of the negative or unseen space around an object. The air trapped inside a hot water bottle, the space underneath a bed and the interior of a three-storey house - Whiteread turned the traditional process of cast sculpture on its head. The first woman to win the Turner Prize, the most prestigious art award in the UK, Whiteread continues to make work that is remarkable for its ability to comment on themes of absence and loss in monumental and subtle ways.

Accomplishments

- In making the air or space rather than the thing itself the focus of her work Whiteread singularly reinvented the traditional casting process. This was a remarkable achievement in that it helped to redefine the very nature of what a sculpture was.

- Her approach broke new ground in the fact it was based on the conceptual idea of absence - a position that one could perhaps see as almost anti-sculptural.

- Her sculptures deal with psychological space as well as physical space. Evoking themes of absence and memory, their sheer presence in specific sites - such as deprived areas of East London and the Holocaust Monument in Vienna's Judenplatz - provide an affecting social and political commentary.

- Repetition is key to her work - as Whiteread herself noted in her remark that "I've done the same things over and over". However, even in her series of hot water bottles, mattresses, or translucent resin cubes, the slight imperfections and subtle color changes help create variety and a sense of time passing.

Important Art by Rachel Whiteread

Closet

In both scale and ambition Closet (1988) - the inside of a wardrobe cast in plaster and covered in black felt - is a remarkably powerful work. Whiteread exhibited this piece along with four other cast plaster works in her first solo exhibition after graduating from the Slade. Whiteread described the process of making Closet as follows: "I simply found a wardrobe that was familiar, somehow rooted in my childhood. I stripped the interior to its bare minimum, turned it on its back, drilled some holes in the doors and filled it with plaster until it overflowed. After the curing process the wooden wardrobe was discarded and I was left with a perfect replica of the inside." In focusing on the negative or unseen space contained within the wardrobe - a familiar domestic object - Whiteread set a pattern for her own work for years to come. Unlike other cast sculpture, her works weren't simply replicas of themselves. And, in a further imaginative twist, they positioned us on the inside looking out.

An elegant, tall, dark monolith, Closet relates in formalist terms to both the serial minimalist sculpture of Donald Judd and the abstract zip paintings of Barnett Newman. As her own description suggests, Whiteread's approach is largely functional and process-driven, although also related to a childhood memory of hiding in a dark cupboard. Unlike some of her YBA contemporaries (whose own debut exhibition also took place in 1988) Whiteread is less interested in telling personal narratives but allows her materials to speak for themselves and by association create a series of emotional and sometimes nostalgic references. Here, the generic nature of the wardrobe chosen and its suffocating black felt cover help conjure up a confined space, recalling scary moments in childhood games of hide and seek.

Plaster and black felt - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Untitled (Torso)

Whiteread made this early small-scale, flesh-colored work by casting the inside of a hot water bottle in plaster. Through its title, the piece refers to a torso, a body without limbs or head, which in turn introduces the idea of the way in the body is fragmented in classical sculpture. Yet, Whiteread's sculpture is far moved from classical sculpture. In this context, it is hard not to see Untitled (Torso) as making a knowing reference to Whiteread's own position within the art historical tradition - how even at this early stage her conceptual and process-led approach presents a real challenge to traditional sculpture.

However the overwhelming sense that this fragile, chubby little sculpture (one of many such works) evokes is its connection to a small living thing - a baby lying naked on its back perhaps. The work elicits a bodily and psychological reaction to an object that is at once unremarkable, powerfully intimate, and deeply unsettling. A hot water bottle is a source of warmth and comfort, to be hugged to the body. In Whiteread's formulation, however, it is devoid of warmth and despite its tactile shape it is far from huggable. This points to Whiteread's ability (fundamental to her career and to her contribution to contemporary art) to create a sense of the uncanny and to imbue an ordinary object with emotive power.

Pink Dental Plaster, waxed

Ghost

Ghost was Whiteread's breakthrough, ensuring her reputation as an important contemporary artist. By this point, Whiteread had started to make casts of much larger domestic architectural features such as fireplaces, baths and sinks. Her ambition was to create a negative plaster cast of an entire room in a house and she took the opportunity of a solo show at London's Chisenhale Gallery to realize this monumental idea.

Having located a house, Whiteread began the painstaking process of filling an entire room with plaster. She settled on a Victorian parlor at 486 Archway Road in north London, partly because it offered her the simple, clean lines of a doorway, window and a fireplace. In preparatory drawings, Whiteread used a grid system to divide the walls into sections, using proportions from works by the Italian Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca, heightening the links between her practice and the history of art. Each section of the room was reassembled then facing outwards on a steel frame, creating an exact three-dimensional version of the room, but inside out and produced in pale plaster.

Ghost is tomb-like and spectral - Whiteread herself talks of how she was trying "to mummify the air in the room." The room appears both familiar and unfamiliar, a domestic space deprived of its normal uses and functions. From far away, the work appears almost abstract, but walking around the work makes the domestic proportions obvious to the viewer, and tiny details such as light-switches and keyholes are revealed on closer inspection.

Visually the work connects to Minimalism, making Ghost an important response to works by artists such as Donald Judd and Carl Andre (notably, the Tate had just acquired Andre's firebricks work Equivalent VIII (1966), a move that was highly criticized by the tabloid press). However, Whiteread transforms the visual language of Minimalism by applying domestic proportions and details to the cube.

Plaster on steel frame - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Untitled (House)

Untitled (House) was Rachel Whiteread's most ambitious sculptural work. It is also the work with which she is forever associated. Using the same reverse casting technique she used to produce Ghost (1990), Whiteread made a concrete cast of the interior of an entire three-storey house in London's East End ¬ - the basement and the ground and first floors, including all the stairs and bay windows but not the roof. The work attracted countless visitors but caused an uproar in the popular press and was eventually destroyed by the council. However, it also won Whiteread the Turner Prize and the acclaim of the art world.

Curator and art historian Ann Gallagher explains its importance in the following way: "A landmark, if temporary, public sculpture, Untitled (House) has come to epitomize what has remained Whiteread's lifelong project as an artist: that of fusing everyday vernacular forms with personal as well as universal human experiences and memories." Whiteread's piece was remarkable for its wealth of associations, which were personal, political and social. Untitled (House) forced the viewer into an uncomfortable relation with architecture; by turning the house apparently inside out, the viewer is psychologically placed both inside and outside the building, evoking simultaneous feelings of inclusion and marginalization.

Furthermore, Untitled (House) challenges ideas of the domestic and the concept of "home". Although Whiteread's house contains domestic details, its brutalist concrete appearance makes the structure feel forbidding and devoid of the things that we consider when we think of a home. Through its sheer presence in the East End in the early 1990s, Untitled (House) became a social and political statement ¬spotlighting the unpopular redevelopment policies that were being aimed at some of London's most deprived areas by local councils.

Plaster and steel frame - now destroyed

Water Tower

For her first public sculpture in the United States, Whiteread wanted to find a typical symbol of New York to cast. She settled on a water tower, and originally installed the work on the roof of a building in Soho between two functioning water towers. The use of translucent resin gives the work an ethereal quality and allows the appearance of the piece to change throughout the day with the light and the weather. Sometimes it stands out clearly and other times it blends in with its surroundings, much like the real water towers on which it is based. The effect is to encourage New Yorkers to relook at an important and iconic architectural feature of their city, and remind themselves that it is often forgotten or overlooked.

In this piece, Whiteread plays on her role as an outsider. The resin tower is introduced to the skyline among other objects that initially appear to be almost identical to it. The artwork becomes an immigrant in this context, revealing difference through similarity and causing the viewer to question what differentiates an art object from ordinary objects.

James Middlebrook, an art engineer who worked on citing the work, argues that, in this context, "the work can be understood as a dialogue with the iconic, a discussion that is particularly relevant in a city that boasts so many famous objects and celebrated vistas within its landscape; such an interpretation is underscored by Whiteread's creation of a postcard in which her piece was humorously presented next to landmark buildings and sculptures of the city, such as the Empire State Building and the Statue of Liberty. The recognition of the Dada-like condition within this and similar projects that iconize the generic reinforces the notion that the particular within this piece represents a wider field; the water tower calls attention to all water towers, and possibly all urban water tanks and domestic plumbing systems." Thus, he emphasizes the way in which Whiteread draws on the visual language of infrastructure, turning the technical functioning of the city into a topic for contemplation and consideration.

Resin and steel - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Holocaust Memorial

Whiteread's Holocaust Monument marks one of her earliest public sculptures, an aspect of her practice that has been increasingly important to her career. Located in Vienna's Judenplatz, the work is a memorial to the victims of the holocaust, and consists of an inside-out library. The solid concrete block appears to be a room with closed doors, but the walls are lined with books whose pages face towards the viewer. The site-specific work responds to the architecture of the square in which it is placed, and it is an important example of anti-monumentalizing the concept of a memorial sculpture. Emphatically mute and austere, the work is nonetheless a fitting and sensitive response to an overwhelmingly shocking historical event.

Also known as the Nameless Library, the piece presents the viewer with row upon row of blank casts of books. In erasing their titles, authors and contents Whiteread allows a full range of associations from the Jewish community's identity as the People of the Book to Nazi programs of book-burnings as a way of repressing radical thought. The books also prompt the viewer to think about memory, and how some forms of loss are too devastating to be expressed in words.

As art historian Rachel Carley argues, "Under Whiteread's direction, the ability to open up the diegetic space of the book, a space of narrative passage that moves between scales through time has been foreclosed. Whiteread chose to cast books of the same height, endowing them with an association to the encyclopaedic and bureaucratic, lending the work allegiances to the Nazis' obsession with bureaucratic procedures and record-keeping. The books on the memorial make reference to a knowledge base that has been eradicated, alluding to the stories unable to be told, just as the lives of the authors were stopped short."

Concrete - Judenplatz, Vienna

Embankment

In 2005, Rachel Whiteread was asked to produce a commission for the huge Turbine Hall at London's Tate Modern. Her resulting work, Embankment, consists of 14,000 translucent white polythene casts of cardboard boxes. Like giant sugar cubes, the boxes were stacked in large piles that towered over viewers as they wandered at random among them. Embankment is reminiscent of a winter landscape and it is significant that Whiteread visited the Arctic earlier in the year, while the title also suggests a relationship to London's Embankment (the area around the River Thames), viewed perhaps in the pale light of day.

The work was inspired by Whiteread's experiences following the death of her mother. Going through her mother's things before packing them up again, the artist was struck by the emotional significance of the humble cardboard box, reflecting on how it is often present at significant times in people's lives. Whiteread made casts of ten of the boxes from her mother's house, and multiplied these, pointing ostentatiously to her sculptural process of transformation through replication and reproduction. She also demonstrates how everyday objects can be imbued with power and significance through simple acts and small changes of material, color, or scale.

Polyethylene boxes - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Biography of Rachel Whiteread

Childhood

Born in Ilford in Essex, Rachel Whiteread moved to London when she was seven. Her mother, the artist Patricia Whiteread, was involved in important exhibitions of feminist art at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts in the 1980s. Consequently, Whiteread and her older twin sisters grew up surrounded by art and materials for art making. Her father Thomas, a geography teacher, supported his wife's artistic career, and converted part of their house into a studio, where Whiteread remembers helping to install a concrete floor as a child. The artist has frequently cited the importance of her upbringing to her later artistic practice, feeling a particular debt to her geographically minded father, "whose interest in industrial archaeology enabled me to look up" and appreciate concepts of architecture, spatiality, and memory.

As a child, Whiteread was sent to a progressive public school, which she remembers as "awful [...] but I kind of loved it; it was a big world soup, fights all the time, influxes of Bangladeshis, Greeks, Turks, Romanians, a really interesting bunch of people all thrown together. I wasn't good at school. I didn't behave or sit down, I mucked about, doing what I could do to get by."

Early Training and Work

After school, Whiteread studied fine art on a foundation course and then painting at Brighton Polytechnic. While she was at Brighton, she studied under British sculptor Richard Wilson, who taught her the casting technique that would be so vital to her later career. She applied for courses in both painting and sculpture at London's Slade School of Fine Art, and chose sculpture, revealing later that "I couldn't make things stay on the wall ... they always ended up on the floor". At the Slade her tutors included Alison Wilding and Phyllida Barlow, two highly revered sculptors working today.

By the time she graduated in 1998, Whiteread had hit upon her signature style, casting the negative spaces inherent in everyday objects. The year after she graduated, Whiteread had her first exhibition at a small London gallery, where she showed just four pieces. These included casts of the interior of a wardrobe and the space underneath a bed, works which marked the beginning of her mature period.

At this time, she was living in East London and her a studio was part of a large complex in Carpenters Road in Stratford. She remembers her time there fondly, but recalls that the area was quite run-down at the time: "There were a few of us: Grayson Perry, Fiona Banner, Fiona Rae, Simon English. It was a sort of silent club: if you could survive Carpenters Road, you could survive anywhere. It was the Badlands."

Although Whiteread knew other artists of her generation, she always felt separate from them due to her lack of interest in being in the media: "People like Grayson Perry, who I shared a studio with back when he was still struggling, great show-offs who want to be in the media all the time... It's not for me."

Mature Period

Whiteread's self-assurance in her own practice (which has changed remarkably little in the last 30 years) is perhaps what helped her to become well known and respected relatively quickly. In 1990, at the age of 27, Whiteread created her early masterpiece Ghost at London's Chisenhale Gallery, and was subsequently nominated for the Turner Prize. In 1992, one of her pieces was selected for the prestigious Documenta IX exhibition. She was also included in exhibitions of work by Young British Artists such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas, even though she was not generally a part of that group.

The following year, Whiteread produced arguably her most important - and certainly most debated - work. Untitled (House) was a cast of an entire Victorian terraced house in London's East End that had been scheduled for demolition. The work, which was shown in situ, caused huge public controversy, and became a symbol of "contemporary art" in the press (for those both for and against it). Some critics loved it, but a petition for its removal received a large number of signatures. Whiteread recalls that it was very unusual for the general press to be interested in contemporary art at the time: "You have to remember, it wasn't like it is now, with art being this rock 'n' roll thing with the media."

Whiteread was awarded the Turner Prize in November 1993 (the first woman ever to achieve this), but the local council ruled that Untitled (House) should be destroyed on the same day. Whiteread was also awarded £40,000 for being the "worst artist of the year" by the K Foundation ¬- a pop music duo whose career had made them enough money to burn - who claimed they would set light to the cash if she didn't accept it. Whiteread found the whole process stressful and ended up accepting it and then giving most of it away. In January 1994, House was destroyed; the contractor chosen to carry out the task claimed "'It's not art, it's a lump of concrete." The art world, however, was outraged, seeing Untitled (House) as an important milestone in contemporary art.

In 1995, Whiteread's work was shown as part of the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

In the same year, she was awarded a commission to produce a memorial to the holocaust in the city of Vienna. As part of the planning and fabrication process, the artist travelled in Germany and Eastern Europe to sites where Nazi atrocities took place and to cemeteries and battlegrounds, deepening her understanding of the issues. Due to the political and sensitive nature of the commission, it took five years to come to fruition, but it also led to a series of public and institutional commissions for Whiteread from around the world.

In 1999, Whiteread and her partner - the sculptor Marcus Taylor - bought a former synagogue in Bethnal Green, London, which had most recently been used as a place for storing textiles. Whiteread spent several months using her casting method to get to know the building and its architectural elements. In the years that followed, the area became fashionable, partly due to the influx of artists and designers during the early 2000s. Whiteread and her partner later moved away, but when asked if she felt guilty about adding to the area's gentrification, she replied: "Guilty! For changing Shoreditch? No. We bought a weird building that had been empty for years, and it took people like us to work out a way of living there."

In 2003, Whiteread was pregnant with her first son, Connor, when her mother unexpectedly died after a routine operation. Whiteread and her sisters waited a year before they felt able to go through their mother's possessions. It was this experience of encountering boxes of objects and images from her childhood that inspired her to make a series of works based on cast boxes, including her huge 2005 Tate Modern installation Embankment.

Current practice

More recently, Whiteread has cut down her studio size and is working with fewer assistants. Consequently, her recent work has been on a smaller scale than the earlier monumental pieces from the 1990s and early 2000s.

In 2007, she gave birth to her second son, Tommy. After this event, Whiteread began to introduce more color into her work, where white, grey and organic colors had previously predominated. Some of these works include translucent resin casts of windows and doors. She has also taken on a number of commissions creating casts of small sheds for locations including London, New York, and Norway.

The Legacy of Rachel Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread is one of Britain's leading contemporary artists. As the first woman to have won the Turner Prize, Whiteread is an important figure for many contemporary female artists especially in having developed a way of working that is not focused on women's issues or on an explicitly feminist view point - indeed the industrial scale and materials of many of her sculptures takes any consideration of her work beyond any reductionist reading around gender.

Whiteread's remarkably consistent use of the casting method has changed perceptions of how an artist can create variety within their practice; rather than experimenting with different media, she has used the same basic method to push the media of plaster and resin to their limits. In her work she continues to experiment with ideas around space, perception and memory creating, through allusion and suggestion, pieces that have a highly emotional and sometimes political content. Although not an actual part of the group, Whiteread's loose association with the Young British Artists movement also meant that she is part of a key legacy that would influence British art for several years.

Influences and Connections

-

![Bruce Nauman]() Bruce Nauman

Bruce Nauman -

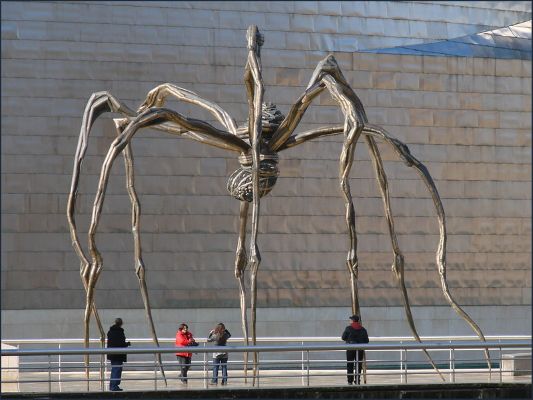

![Louise Bourgeois]() Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois - Richard Wilson

- Alison Wilding

- Richard Deacon

- Marcus Taylor

- Angela de la Cruz

- Karla Black

- Contemporary Sculpture