Summary of Anni Albers

Pioneering German American Textile artist and printmaker Anni Albers revolutionized the percep-tion of weaving as a serious art form. Trained at the Bauhaus School and later a teacher at Black Mountain College, Albers merged modernist abstraction with the ancient craft of weaving, trans-forming thread into a language of structure, form, and expression. Initially skeptical of textiles, she embraced the medium's constraints, using them as a challenge that offered creative disci-pline. Through experimentation with materials, both traditional and industrial, she produced intri-cate, geometric compositions that bridged fine art, design, and architecture. Her work spanned handwoven tapestries, large-scale commissions, and graphic prints.

Accomplishments

- Albers can be seen as a proto-feminist figure within the weaving movement, challenging the mar-ginalization of textiles as "women's work." By elevating weaving into a site of conceptual and formal innovation, she not only expanded the possibilities of modernist abstraction but also dis-rupted gendered hierarchies in art. Her rigorous, experimental weavings asserted that Textile arts could carry intellectual weight equal to painting or sculpture, reclaiming a traditionally feminized medium as a space of radical artistic expression.

- At Black Mountain College, Albers established and led the weaving program, influencing genera-tions of artists, including Ruth Asawa and Robert Rauschenberg. Her teaching emphasized mate-rials, process, and imagination, reshaping how textile education was approached in America.

- Albers' book On Weaving remains a foundational text in fiber arts and design theory. It explores both the philosophical and technical dimensions of weaving, emphasizing the material intelli-gence and aesthetic potential of fiber-based work.

- In a historic milestone, Albers became the first weaver ever to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This exhibition traveled throughout the United States, legitimizing textile art in the eyes of the mainstream art world.

The Life of Anni Albers

A visionary of modern Textile Art, Anni Albers transformed weaving from a so-called "women's craft" into a radical form of modernist expression. Blending Bauhaus discipline with fearless ex-perimentation, she wove thread into geometry, architecture, and philosophy - showing that cloth could carry the same intellectual force as paint or stone. Her work continues to inspire artists and designers who see in her weavings not just patterns, but a language of thought and resistance.

Important Art by Anni Albers

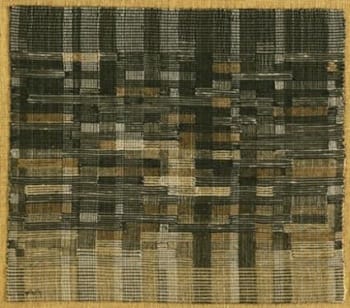

Untitled Wall Hanging

Untitled Wall Hanging is a bold composition of horizontal and vertical stripes and blocks, woven in synthetic silk and textile fibers. Dominated by a restrained palette of soft taupe, muted tan, black, and bright red, the pattern evokes a grid-like rhythm. The clean geometry and sharp con-trasts reflect a carefully structured abstraction, embodying both formality and visual energy.

Decorative wall hangings of this sort comprised some of the Bauhaus weaving workshop's most successful products, along with shawls and blankets, yet this was also a space for Albers to experiment and innovate. This piece was one of the first to include new synthetic fibers, including artificial silk, which although radical at the time, would later become standard materials for mass-produced textiles. The pattern is based on repeating and interlocking forms of stripes and blocks, created with a triple-weave technique. Unlike her colleagues, she adopted a palette of neutral threads and focused her attention on complicated weaving techniques and modern geometric design. This reflected, in part, her intention to create designs that could eventually become models for industrial mass production. Her limited use of color was also influenced by contemporary theories of color relationships, often reflecting the glass artwork of her future husband Josef Albers.

At a time when weaving was considered "women's craft," Albers transformed it into fine art. This piece exemplifies her role in legitimizing weaving as a medium capable of conceptual abstraction and serious aesthetic presence.

Synthetic silk, synthetic fibers - Museum of Modern Art, New York

Necklace

Necklace consists of a ball-chain suspending a circular sink strainer pendant embellished with dangling paper clips. It reflects an interesting side interest of Albers' while working at Black Mountain - jewelry.

Inspired by the combinations of precious and non-precious materials of pre-Columbian jewelry, which she and her husband Josef saw during a trip to Oaxaca, Mexico, Albers and her student Alex Reed began to design objects based on common household items. She wrote that the ancient artifacts "gave us the freedom to see things detached from their use, as pure materials worth being turned into precious objects."

Beginning in 1940, their collaboration resulted in a series of anti-precious jewelry, constructed from elements purchased at hardware stores or local five-and-dimes. Imagining new uses and unique patterns from unassuming materials such as washers, ribbon, nuts, chains, or bobby pins, their jewelry emphasized the modern materiality of these objects and did not attempt to transform them into something more refined or expensive.

This piece subverted expectations of jewelry as luxury. Although some critics ridiculed the collection for its common materials, their criticisms revealed the popular expectations of jewelry as a sign of economic display and ostentatious indulgence. Yet the art world celebrated its innovation, acknowledging the imaginative workings of familiar objects, conceptual clarity, and beauty despite its humble origins.

This necklace was part of a travelling exhibition of handmade jewelry in 1941-46, shown across sixteen U.S. museums. It stands as an important early example of conceptual, craft-based jewelry that reshaped perceptions of ornament and material agency in modern art.

Metal chain, dish drain, paper clips - Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

In Orbit

In Orbit features a tightly structured grid background interrupted by two concentric ovals and a bright yellow cross. These elements suggest planets or satellites in orbit, introducing dynamic cir-cular motifs within a geometric framework. The wool is so densely woven that it appears to have monumental weight as though it were made of concrete.

While highly geometric, the work is not totally abstract. The grid alternates with segments of light and dark threads, predominately keeping within a palette of muted neutrals, golds, and yellows. Her inclination to abandon pictorial imagery is strong. Instead, Albers chose to emphasize the reduction of celestial objects in an aesthetically pleasing and meticulously arranged composition. She favored motifs that were commonly utilized among her contemporaries.

Her use of double-layer leno weave allowed novel visual effects: hidden color and depth introduced into traditionally planar textiles. Because of the innate vertical lines of the warp threads, those that are strung in the loom as the beginning structure, the addition of a grid pattern is only natural. Albers manipulated the weft, the threads that are carried through the warp to create the textile's pattern, to emphasize instead of erasing the grid. This technical sophistication was central to her broader experimentation with materials and weaving techniques.

In Orbit exemplifies a transitory period in Albers' work. After she and Josef moved to Connecticut in 1949, she dedicated all of her energy to her artistic output and began creating pictorial weavings, or woven works that were intended to be hung vertically on walls as independent artworks. This prime example blends an understanding of traditional weaving methods with the geometry and structure of modern architecture.

Wool - Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut

Under Way

Under Way features a dynamic central panel of deep black wool with vibrant red and white loops and squiggling lines that seem to float across a neutral background. The energetic red-and-white stands in high contrast against the darker weave, creating a rhythmic, meandering pattern across the surface. Each wave of color is slightly raised from the base of the textile.

This iconic work reflects the merger between Albers' geometric designs, bold color palettes, and inspiration from Peruvian textiles. At the time of its creation, she and her husband Josef had amassed an impressive collection of Central and South American art. The pre-Columbian artists in this era predominantly used colors gleaned from natural materials that produced rich red hues, stark whites, and deep charcoal blacks. The end result is a composite jacquard fabric - a textile where intricate woven patterns are combined with other materials or layers to create a unique and often more functional material.

Under Way is a masterful example of Anni Albers's exploration of dynamic thread movement across a structured woven backdrop. The striking contrast between deliberate geometry and organic flow - paired with rich textures and material complexity - marks it as both visually powerful and technically inventive. It plays a key role in the narrative of mid century Textile Art: a turning point where weaving transcends functionality to become expressive, multisensory fine art.

Cotton, Linen, Wool - Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC

Line Involvements IV

On a textured, dark background, slender white lines twist and intertwine, forming a complex, knot-like central tangle from which some lines extend horizontally outward. The contrast creates a dynamic interplay between the chaotic central form and the radiating parallel lines. Though ex-ecuted in ink, the work echoes weaving: the lines evoke threads or yarns, intertwining in a lay-ered composition. Albers treated the lithographic surface as if weaving - lines engage, knot, and communicate like fibers in textile structures.

Albers' journey into printmaking began when her husband Josef was invited to Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles on fellowship. During the summer of 1963, Anni watched closely as Josef immersed plates in acid to reveal intricate designs. Intrigued by the process, she was drawn into the methodical nature of printmaking. June Wayne, the director of the workshop, invited Anni to experiment with her own printmaking. Albers' creative success earned her an invite back to the fellowship in 1964. This creative revelation occurred around the time when Albers was considering her move away from solely creating textiles. Printmaking provided the structure that she creatively craved while also allowing her to meticulously manipulate the individual elements of the prints and plates.

In this exploration of new mediums, she reflected on her earlier works for inspiration and subject matter. The composition of Line Movements IV closely resembles her earlier gouache work, Knot, from 1947. As a series, the works reveal Albers' interest in the meandering line when juxtaposed with the structured grid. Each of the seven lithographs were hand printed on individual sheets of paper and then enclosed in a portfolio-style folder made of Japanese paper. Her objective was to begin with the simplest form, the line, and make each successive print more complicated as the line journeys through the works.

This series established Albers' reputation beyond weaving - as a printmaker with deep conceptual coherence. She extended her Bauhaus-rooted design thinking into graphic media, influencing later generations of artists interested in abstraction and structure.

Lithograph - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Six Prayers

Six Prayers is comprised of six individual panels woven in a muted palette of grey, beige, brown, and off white, with silver metallic thread subtly interspersed to create highlights and shimmering accents. Each panel features unique weaving textures - alternating areas of dense structure and open warp/weft interplay, separated by narrow unadorned bands. Metallic accents punctuate the somber tones, creating a rhythm of depth and glimmer across the sequence. Displayed with slight spacing between each vertical strip, the ensemble evokes the ritual spacing of prayer shawls, with a meditative cadence enhanced by the alternating texture and tonal variation.

In 1965 The Jewish Museum in New York commissioned Albers with the challenging task of memorializing those who died in the Holocaust. Faced with the impossible task of capturing the lives of millions, she instead created a space for thought, allowing the viewer to find more specific meaning themselves. The vertical panels recall the shape of burial markers or scrolls of text but can also be read as pure abstractions of line and color. The choice of six panels references the six million Jews murdered by the Nazis.

The panels are not woven uniformly, but rather the black and white threads vary against the structure of the grid. They create a pattern that ebbs and flows, suggestive of any number of individual paths within the whole. The process of weaving takes on additional significance in this work as a reference to tikkun, the notion of "social repair" central to Jewish identity.

Critics and historians consider Six Prayers one of her most profound works - a mature synthesis of abstract Textile Art, memorial intent, and formal rigor. It showcases weaving not just as craft, but as a serious medium for modernist expression and emotional resonance.

Cotton, Linen, Bast and Silver Thread - Jewish Museum, New York

Camino Real

The composition of Camino Real features a rhythmic array of triangular and zigzag motifs in var-ying shades of red - from deep carmine to bright pink - creating an optical vibration across the surface. Light-toned triangles subtly project outward while darker ones recede, crafting a tex-tured, spatial illusion that pulses across the felt ground.

The felt ground on which this piece was made was originally created for the lobby of the Mexico City Camino Real Hotel, for which architects Ricardo Legorreta Luis Barragin commissioned Albers' tapestry. Albers purposefully drew inspiration from the geometric designs that are prevalent in traditional Mexican weavings. The forms evoke ziggurats and steppe geometric patterns found in ancient Mesoamerican sites, rendered through her modernist emphasis on balance, economy, and structure.

The tapestry had not been outside of Mexico City since its hanging in the hotel in the 1970's. It was thought to be lost until it was rediscovered in 2019. After having not been seen for over thirty years, two writers happened upon the rolled-up masterpiece while they were doing research for the hotel's fiftieth anniversary. After four months of careful restoration, the work was shown outside of Mexico for the first time ever at an exhibition at David Zwirner in New York.

Camino Real is the largest tapestry that Albers ever created. After working on a relatively small scale for so many years, to achieve such a monumental scale took careful planning and collaboration. Albers worked with a Manhattan-based company, Abacrome, who had worked with other artists such as Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenburg.

The work stands as a peak example of Albers' late-career ambition - blending material innovation, public scale, and cultural dialogue. It represents a pivotal moment when her textile vocabulary broadened into the realm of architectural space, and her practice opened toward graphic media.

Wool Felt on Cotton Support - Originally installed at the Camino Real Hotel, Mexico City

Biography of Anni Albers

Childhood

Anni Albers, born Annelise Fleischman, experienced a childhood marked by the intersection of generational wealth and independent craftsmanship. Her father ran a successful business as a luxury furniture manufacturer and her mother was a member of the Ullstein family, known for their prodigious publishing company that, at the time, was the largest in the world. Although Albers heralded from the union of two prominent German Jewish families, she was confirmed in the Protestant church as a child . Most of her family converted as a collective effort to assimilate into German Protestant society and secure social acceptance, rather than a straightforward religious shift.

Albers showed interest in the artistic process at an early age. This desire motivated her mother to enroll her in formal art classes, during the 1910s, to encourage her artistic development . Albers practiced oil painting, watercolor, and other mediums, and, in her late teens, studied under the famous German Impressionist Martin Brandenburg.

While she briefly trained at the School of Applied Arts in Hamburg in 1919, she left the program in search of more fulfilling artistic exploration beyond historically traditional methods. Though she was trained in painting, she found the "tremendous freedom" of a blank canvas intimidating and creatively stunting and craved more structure and security from her practice.

Education and Early Training

Albers began studying at the Bauhaus School in April 1922 when she was twenty-three years old. The Bauhaus was a groundbreaking German art and design school that sought to unify fine art, craft, and industrial design. The innovative learning environment was unlike anything Albers had encountered before. Professors and students had collaborative, and even sometimes argumentative relationships that helped to evolve the ethos of the school. A top thrust within the school was to instill students with intellectual and theoretical approaches to both fine art and design.

While there, she met Josef Albers. He was, at the time, a renowned glass artist in the school, but would later become known as a pioneering artist, educator, and theorist whose groundbreaking explorations of color, form, and perception - most famously in his Homage to the Square series - reshaped modern art and design education at the Bauhaus, Black Mountain College, and Yale. The pair connected immediately over their shared admiration of the Bauhaus creative principle of form following function and their intuitive, exploratory natures. They would marry in 1925, solidifying their personal and artistic bond. Josef was instrumental in supporting Anni, both as a peer and instructor, throughout her time at the school. Artists of the Bauhaus would undergo a preliminary year and then choose a workshop on which to focus. Although Anni was initially denied admittance to her preferred workshops, Josef helped her with an additional round of testing so that she was admitted to the weaving workshop.

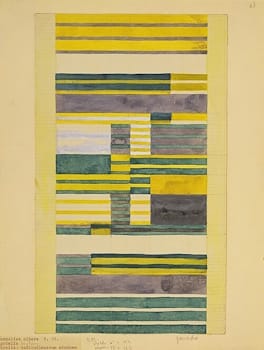

A subtle yet potent turning point: this gouache sketch reveals Albers transitioning from painting to textiles, envisioning the modernist geometry that would define her groundbreaking weavings.

Anni reluctantly entered the weaving school since she, and many other women, were systemically barred from most other practices. She yearned to join Josef in the glass workshop, where she thought her talents would be more aptly applied outside of the restrictive two-dimensional plane. Anni considered weaving to be a "sissy" practice that relegated women to the fringe of artistic production into the underappreciated domain of craft. But the weaving workshop changed the trajectory of Textile Art - it was no longer a practice of needlepoint relegated to sitting rooms; textiles could be innovative, monumental, and moving.

Despite her dislike of the restrictions that led her to the weaving workshop, she soon found that the confines of the weaving practice allowed her to expand her understanding of weaving as a means of visual communication and material exploration. Albers thrived in this great period of creative consideration. Senior artists such as Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky had not yet become revered masters of their practice yet were artists tearing their practices down to their foundations in order to rebuild them in a new, innovative image.

Albers learned to experiment within the basic structure of weaving and textile design, becoming one of the most prolific and renowned members of the workshop. As one of the Bauhaus's few profitable workshops, weaving was vital not only artistically but institutionally: it demonstrated that modern craft could be translated into designs for mass production. For the Bauhaus, this wasn't simply a matter of revenue - it embodied the school's radical mission to unite art and industry, proving that beautiful, functional design could be accessible to everyday life while also ensuring the school's survival.

Mass production was framed as a way to make good design accessible to everyone, not just the wealthy elite. If Bauhaus designs could be produced affordably, they would fulfill the school's social mission of uniting beauty with everyday life. Teaching students how to earn a living was practical, not just ideological. By collaborating with industry, Bauhaus artists could ensure their own careers.

In 1924, Albers published an essay, "Bauhaus Weaving" that described both a history of weaving and spoke to its future potential. Noting that very little had changed structurally from the "ancient craft" of textile weaving, she stressed that modern equipment had not revolutionized the basic grid structure of woven cloth. She lamented that current mass production had lost contact with the materiality of weaving and that the divide between designers and weavers had led to poorly designed and poorly crafted products. The Bauhaus weaving workshop, with its synthesis of design and craft emerged as the solution to this industrial stalemate. While she celebrated the handloom (which she would continue to use in her own work), she ended the essay with a vision for modern textile production, based on the designs and materials developed through craft-based experimentation.

Albers made her mark on the Bauhaus, the weaving art form, and the conception of "women's" crafts with her work. Beyond the integration of abstract modernism into textile weavings, Albers also introduced new technologies to the workshop. When the Bauhaus won a commission for the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gerwekschaftsbundes (ADGB) School, it was a testing ground for their ability to craft industrially feasible designs. Albers developed a set of textiles for the ADGB auditorium, using different types of synthetic fibers and cellophane to create acoustic panels. Her research into these materials influenced the manufacturing of similar panels and led to new innovations in theater design.

Anni received her diploma in 1930, and she and Josef stayed at the school as teachers. The Bauhaus suffered as the geopolitical climate of Germany descended in the wake of World War II. In 1933, rather than comply with the regulations of the Third Reich, the Bauhaus staff elected to close the school after immense pressure from imposing political powers. This left students and staff such as the Alberses without employment or a place to convene with their fellow artists and friends.

There was a keen awareness among the Bauhaus artists that Anni's Jewish heritage would make her a target of the Nazi's advances through Germany. With this in mind, the Albers were began contemplating their options for surviving in this frightening new era. In the summer of 1933, they were approached by the American architect Philip Johnson. Johnson greatly admired Anni's textile work, and he helped foster the connection that would bring the Alberses to America. Johnson introduced the Alberses to Edward Warburg who helped fund the groundbreaking Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

Escaping Nazi Germany, the Alberses moved to North Carolina to fully commit to their tenure as professors at Black Mountain College. From their arrival in 1933, Anni was an assistant professor, and Josef was the creative epicenter - chosen to be the head of the painting program. In 1934, Albers founded the Black Mountain College weaving program which she spearheaded until the school's closure in 1956. Although her pedigree was quickly rising, Albers' textile classes were still dismissed outside of the close-knit community of Black Mountain College. Alongside Albers, Franziska Mayer, a Swedish textile artist, and Trude Guermonprez, an esteemed textile designer and production weaver, helped shape a generation of artists. Their influence of incorporating textiles, weaving techniques, and Bauhaus design principles can be seen in the works of notable alumni such as Ruth Asawa, Robert Rauschenberg, and Ray Johnson as well as architects like Don Page and Claude Stoller.

Albers' pedagogical approach as the leader of the textile department at Black Mountain College focused on dissolving the disciplinary boundaries of textiles. She wanted her students to challenge the material hierarchy that art history presented. Textile practices deserved the reverence and respect that their counterparts of painting and sculpture had historically received. Anni's teaching methods aimed to push her students to a point where they were imagining the progression of art from a zero point. She wanted them to imagine the progression of art as it made sense to them from the very beginning. Albers would approach her students by having them imagine that they were in a desolate place such as an empty beach or a desert in Peru without clothing, pottery, or even the least aide of technology. When they had clearly imagined this deprivation of materials, she would pose a simple question, "And now what do you do?"

As a challenge, she took her students outside to collect an array of natural materials such as sticks, reeds, and grasses. They were then instructed to "invent" looms out of these found materials before moving on to the Peruvian back strap loom. This was all in an effort to create context for every aspect of weaving leading to automated factory looms and production. She wanted them to viscerally imagine what a textile could be, its uses, and its material origins. By utilizing the architectural nature of intertwining layers of weft and warp, Albers made often small-scale textile works analogous to the scale and effort of architecture.

While traveling in Europe, the Alberses saw pre-Columbian art in museums, and they were eager to explore the places that produced such innovative works. Along with friends and colleagues from Black Mountain College, the Alberses traveled to Mexico and further into South America over a dozen times between 1935 and 1967. Anni began avidly collecting pre-Columbian and Peruvian art and textiles. She and Josef amassed a collection of around 1,400 objects from their travels. Albers admired their expansive use of color, form, and technique in pottery and textiles, and went to great lengths to research long-forgotten textile methods employed by these cultures. The geometric designs, repetition of patterns, colors, and abstract forms spoke to Albers' inclination away from representation. She thought of the Peruvian and Mesoamerican artists as her teachers, and she took great care to study and take inspiration from their designs.

Mature Period

After over a decade of teaching and immense creative exchange, Anni and Josef left Black Mountain College in 1949. The couple moved to New Haven, Connecticut where Josef became the chairman of the department of design at Yale. This move marked the beginning of a prolific period for Albers. Now that she was no longer teaching, she could dedicate all her energy to making art and writing two novels, On Designing (1959) and On Weaving (1965).

In 1949, she became the first weaver to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Since the success of her exhibition, the MoMA has accumulated the finest collection of her works. This show then traveled throughout America, showcasing her weavings to a large audience and cementing her reputation as the leading textile designer in the country. Albers' time at the Bauhaus instilled her with a distinct aptitude for the integration of textiles into modern living spaces.

The 1950's saw the beginning of her period of "pictorial weavings," or woven works that were intended to be hung on walls like paintings instead of having a solely utilitarian purpose. Albers focused on combining new and innovative as well as humble, overlooked materials in this series. The juxtaposition of transparent cellophane, metallic gold and silver thread, and natural jute produced visually entrancing pieces that beckon the viewer to sit and immerse themselves in the work.

This 1925 design marks Albers' pivotal transition at the Bauhaus, where she transformed weaving from student exercise into a modernist art form that fused abstraction with functional design.

In 1970, the Alberses relocated to the county of Orange in Connecticut. Josef continued painting and theoretical work, and Anni, at the age of seventy, lessened her focus on weaving and took a dedicated interest in printmaking. Albers became fixated with the methodical and process-oriented nature of lithography. When she left weaving for printmaking, Albers thought that textiles might become a dying art. However, she did not abandon the practice for long.

Josef died in the spring of 1976 after being admitted to the hospital with medical complications. Albers visited her late husband's gravesite daily, honoring their promise that if one were to die before the other, the surviving partner would go by with the day's mail and read the letters while sitting in the car next to the gravesite. After his death, the majority of Anni's time was filled with the tireless preservation of his legacy as well as continuing her own artistic practice. She attended many exhibitions and openings such as the 1983 debut of the Josef Albers Museum in Bottrop, Germany.

Albers died on May 9, 1994, nearly two decades after her late husband Josef.

The Legacy of Anni Albers

Anni Albers' legacy is the radical transformation of Textile Art from a traditionally undervalued craft into a modernist, conceptual, and respected artistic discipline. Through her groundbreaking work at the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College, she redefined weaving as a medium capable of architectural structure, philosophical depth, and aesthetic innovation. She championed the idea that textiles could communicate visually and intellectually - just as powerfully as painting or sculpture.

Her legacy also includes a deep reverence for material and process. In works that merged ancient Andean techniques with modern abstraction, she bridged cultures and time periods, showing that innovation often lies in looking backward as much as forward. As the first textile artist to have a solo show at MoMA and the author of the seminal book On Weaving, Albers set a foundation for future generations of artists working with fiber, print, and form.

Many artists today echo Albers' values, whether in their approach to material, abstraction, gen-dered labor, or process. This includes fiber sculptor Sheila Hicks, multidisciplinary designer and performance artist Tanya Aguiñiga, wire sculptor Ruth Asawa, fashion and textile designer Christina Kim (Dosa), fiber artist Liz Collins, and fiber sculptor Magdalena Abakanowicz.

Her influence is seen not only in fiber art but also across architecture, design, Feminist art, and material studies. She remains a visionary, proto-feminist icon who wove together intellect, intui-tion, and integrity into every thread of her output.

Influences and Connections

-

![Josef Albers]() Josef Albers

Josef Albers -

![Wassily Kandinsky]() Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky - Gunta Stölzl

-

![Bauhaus]() Bauhaus

Bauhaus -

![Textile Art]() Textile Art

Textile Art - Pre-Colombian Art

-

![Robert Rauschenberg]() Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg -

![John Cage]() John Cage

John Cage - Ruth Asawa

-

![Paul Klee]() Paul Klee

Paul Klee -

![Josef Albers]() Josef Albers

Josef Albers - Franziska Mayer

- Trude Guermonprez

Useful Resources on Anni Albers

- Anni AlbersBy Brenda Danilowitz, Magdalena Droste, María Minera, Priyesh Mistry, Jennifer Reynolds-Kaye, T'ai Smith

- Weaving at Black Mountain College: Anni Albers, Trude Guermonprez, and Their StudentsBy Michael Beggs and Julie J. Thomson

- Anni & Josef Albers: Equal and UnequalOur PickBy Nicholas Fox Weber

- Anni and Josef Albers: Art and LifeBy Julia Garimorth

- Anni AlbersBy Ann Coxon, Briony Fer and Maria Müller-Schareck

- Anni Albers: Camino RealBy Brenda Danilowitz and T'ai Smith

- The Woven and Graphic Art of Anni AlbersOur PickBy Nicholas Fox Weber

- Josef + Anni Albers: Designs for LivingBy Nicholas Fox Weber and Martin Filler

- Anni and Josef Albers: Latin American JourneysBy Heinz Liesbrock and Brenda Danilowitz

- The Prints of Anni Albers: A Catalogue Raisonne, 1963-1984By Nicholas Fox Weber and Brenda Danilowitz

- Anni Albers and Ancient American Textiles: From Bauhaus to Black MountainBy Virginia Gardner Troy

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI