Summary of Michael Andrews

Michael Andrews stands out as a distinctive figure in 20th-century British art for his ability to weave complex psychological and environmental themes into his work. Known for his versatile style, which ranged from haunting portraits to expansive landscapes, Andrews captured the essence of his subjects with a unique blend of realism and abstraction. His paintings often reflect a deep engagement with the natural world and human experience, and his later work is imbued with a contemplative, almost spiritual quality. What sets Andrews apart is his meticulous attention to detail, his ability to evoke profound emotional and intellectual responses through his use of light, color, and composition and his detailed and eclectic source material.

Accomplishments

- Andrews' preoccupation with the human figure reveals his deep fascination with the complexities of social interactions and the subtleties of personal identity. This interest allowed him to focus on themes of isolation, connection, and the passage of time in his work. Whilst in his earlier "party pieces" these themes are more obvious, some of his later art uses nature as a metaphor for human interactions or contains smaller, more symbolic figures.

- Andrews' keen observation and meticulous depiction of outdoor settings, from the vistas of the Australian outback to the rugged landscapes of Scotland, reflect his deep reverence for nature. Through his work, Andrews invites viewers to consider their relationship with the environment, highlighting the interconnectedness of life and emphasizing both the impermanence and continuity of the natural world.

- In his later years, Andrews underwent a significant transformation in his methods of painting, most notably by creating images through spraying paint onto his canvases. This allowed him to achieve a more atmospheric and ethereal quality to his work. This experimentation can be seen as a forerunner of aerosol art and it influenced a generation of artists who saw the potential of the technique to convey mood and ambiance in innovative ways.

The Life of Michael Andrews

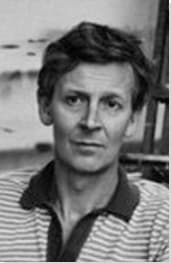

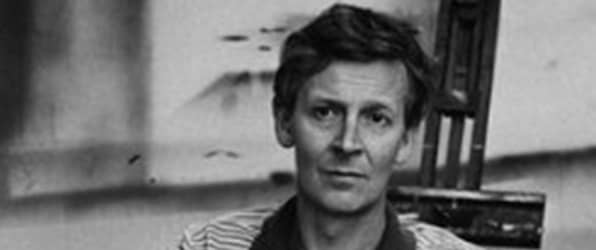

Paradoxically, the shy and reclusive Michael Andrews was obsessed with observing human nature and social interaction, frequenting clubs and parties with fellow School of London artists such as Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, and Frank Auerbach.

Important Art by Michael Andrews

The Deer Park

The Deer Park is one of Andrews' earliest "party pictures" - group scenes that explore human behavior. The painting takes its name from a 1955 Norman Mailer novel, which tells the story of a former Air Force officer (recently discharged due to psychological problems) who moves to the fictional Desert D'Or, California, where he encounters a range of morally depraved Hollywood residents, from movie stars to film executives and pimps. In Andrews' painting, he re-imagines a gathering from Mailer's novel, replacing the characters with the likenesses of iconic historical figures, such as French Symbolist poet, and rebellious thrill-seeker, Arthur Rimbaud (seated front center) as well as Hollywood actresses Marilyn Monroe and Brigitte Bardot, both of whom were known for having torrid love affairs.

Art historian Mark Hallett calls The Deer Park one of Andrews' "painted collages". He notes that Andrews "juxtaposes a mass of visual elements taken from various photographic sources [and tests] out the possibilities of a new kind of painting of modern life, in which the forms of pictorial fragmentation and overlap associated with collage are brought to bear on the narratives and imagery of hedonistic party-going, as expressed in contemporary literature, journalism, photography and film". In addition to the photographs of Rimbaud, Bardot, and Monroe that Andrews' painted from, he also based the background of the image on Diego Velasquez's Philip IV hunting Wild Boar (1632-37). A 1964 issue of Art and Literature included photographs of Andrews' studio, in which he had pinned up vast numbers of images taken from magazines, newspapers, and other sources, suggesting that his process for these "painted collages" involved first collaging found images, which he would rearrange and later paint once he was pleased with the composition.

Andrews' lengthy planning process for The Deer Park (which involved not only collaging found images, but also immersing himself in related novels and films) allowed him to paint it rather quickly, over the course of just a few weeks, which was highly unusual for him. As Hallett writes, "The picture is a hectic and confusing one, and deliberately so. It is structured by the roller-coaster sweep and plunge of a balcony and stairwell down to its left, and by the odd combination of semi-transparent screen and curved viewing platform on its right. This strange, almost free-floating, architecture pours forth a crowd of men and women who variously dance, embrace, sit, and talk, and who spill out into the lush green landscape in the background. The painting's sense of flux and uncertainty is reinforced by its sketch-like and visibly rushed character; it really does have the feel of a picture painted in a hurry".

When The Deer Park was first exhibited in 1963, it garnered rave reviews that called it "one of the most ambitious and original of recent English pictures", "an extraordinary bundle of contradictions and ambiguities", and "a painting of huge ambition".

Oil on board - The Tate, London, England

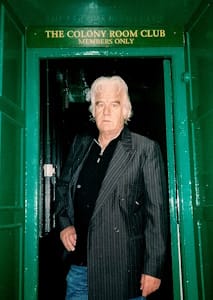

The Colony Room I

Andrews often accompanied fellow artists Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, and John Minton to the Colony Room, a private members' club in Soho founded in 1948 by Muriel Belcher, who had modeled for Bacon. At these gatherings, Andrews' wasn't known to get too involved in drinking and dancing, and it seems that his interest in London's bohemian party scene derived more from his love of observing human social behavior. As art critic Skye Sherwin asserts, "Perhaps the painting says more about the artist than the crowd [...] The sense of his distance is palpable. The bar's green walls suggest an underwater world. It's like peering into an aquarium, where the fish flirt, puff up and quietly peck". It is unsurprising, then, that a few years later, Andrews would produce a series of paintings that explored the parallels between schools of fish and groups of people.

In The Colony Room I, Andrews depicts a typical evening at the club, and depicts several of his friends including Bacon, Freud, and Belcher, as well as writer Jeffrey Bernard, photographers John Deakin and Bruce Bernard, and model Henrietta Moraes. All the figures are engaged in conversations with one another, except for Freud, who stares straight from the painting with what arts writer and curator Tom Morton calls "a glare so scalpel-sharp that it might sober us from a lifetime's boozing". In this way, the figure of Freud challenges the viewer as though they are an incomer to the club, highlighting their separation from the social activity taking place elsewhere and reflecting Andrews' role as passive observer rather than active participant.

Morton describes the style of this, and other "party pictures" by Andrews, as "Edouard-Manet-meets-grimy-pop". Arts writer Fisun Güner calls The Colony Room I "a dour postwar equivalent of a 19th century atelier painting featuring a gathering of esteemed artist colleagues". She also notes that Andrews' "party pictures" juxtapose "isolated moments of violence and hilarity, sexual abandon and existential isolation", and "possess a mind-warping, hallucinatory quality, both disorientating and disconcerting. They also show that Pop art didn't entirely pass him by, as it did Freud, Bacon, Auerbach, and Kossoff."

Oil on board - Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, England

Lights VII: A Shadow

After 1970, Andrews' work changed significantly, both in terms of style and subject matter. His paintings ceased to include human figures, although, as he explained, "I think I'm probably very conscious of there being an onlooker there. In other words whenever there isn't somebody in my picture you can assume there's a visitor looking at whatever the picture depicts". His work at this point became more meditative, influenced by Eastern philosophies such as Zen Buddhism. He also began to experiment with a new method of applying a mixture of water and acrylic paint with a spray gun, creating what art critic Jonathan Jones calls an "eerily tentative and dreamlike" quality, and prefiguring the popularity of aerosol art. Art critic Matthew Collings asserts that, "whatever he understood Zen to be, his surfaces were no longer turbulent, the handling appeared instead almost non-existent, a matter of a few stains and simple outlined forms created using a spray gun and stencils".

Andrews' Lights series of the early 1970s, created in this new style, followed the journey of a hot air balloon as it floated above the countryside. In Light VII: A Shadow, the final work in the series, the shadow of the balloon is visible on a desolate sandy beach, just below a blue ocean. Jones, who has been self-admittedly "haunted" by this work ever since he first saw it, writes that "Painted in flickering yet precise detail, the dark image cast onto bright sand is beautifully real, but it's not real at all. It is merely a shadow. To paint an object just by its shadow recalls the ancient philosopher Plato's claim that we are like prisoners in a cave where a fire burns, seeing not real things but only their shadows on the wall. Andrews seems to be saying that art too is just a shadow, a secondary glimpse of a life elsewhere. When you look at the painting in its opulent frame, you realise that reality is failing in other ways, too. For the great turquoise expanse of sea that laps the beach is not quite in perspective: what at first seems to be a literal depiction looks, on second glance, more like two expanses of abstract colour, blue over sandy yellow. It could be a Mark Rothko abstraction but for the shadow of the balloon. That shadow is all that makes this moment real."

Acrylic on canvas - Private collection

School IV: Barracuda under Skipjack Tuna

Between 1977-81, Andrews produced a series of four paintings titled School, which depict schools of fish. School IV: Barracuda under Skipjack Tuna presents two separate groups of fish above a reef in a vibrant blue ocean. Always fascinated by human behavior, Andrews used the motif of schools of fish as an analogy for the interpersonal behavior and social hierarchies he observed between his daughter and her schoolmates in the playground. The arrangement of the barracuda and skipjack tuna within the composition symbolizes the intricate balance of power and the constant struggle for dominance and survival in the natural world. This also functions as a metaphor for individuals navigating complex social structures, often driven by instinctual desires and the necessity to adapt to their environment.

Art critic Matthew Collings explains that, for the series Andrews "worked out curious new methods of putting a picture together. He took slides, projected the outlines of the photographed fish onto the canvas, drew round them with a pencil, and then improvised methods of animating these flat shapes. He worked with stencilled shapes taped to the canvas, spraying around or within them to create basic silhouettes, and then complicating the effect with further internal shapes, so the impression is of flickering forms". This can be seen as a development of his earlier painted collage technique. This meticulous attention to detail compared with the fluidity of the aquatic setting also underscores the delicate interplay between aggression and harmony, emphasizing the universal nature of these themes across different forms of life.

Acrylic on canvas - James Hyman Gallery, London, England

Permanent Water Mutidjula, by the Kunia Massif (Maggie Spring, Ayers Rock)

In 1983, Andrews took a nine-day trip to Ayers Rock in Australia's Northern Terriotory, a site that art critic Michael Spens calls the "primal psychological and geological hub of Australia". He immersed himself in the environment, repeatedly climbing up and down the enormous mound (which he came to view as a "cathedral"). Spens writes that Andrews "experienced the potency, the latent spiritual energy of the place and its history in a contemplative way". The artist later recalled the experience as an "intensive reckoning". He took hundreds of photographs and did several sketches and watercolors in situ. He also felt compelled to collect samples of the earth, believing that touching it later on would help to reconnect him to that original experience. The next three years would see Ayers Rock as the main subject of Andrews' work. One of these was Permanent Water Mutidjula, by the Kunia Massif (Maggie Spring, Ayers Rock).

This painting draws on the appearances of traditional Aboriginal art, evident in the depiction of the land and water. This is integrated with a Western landscape painting style, creating a fusion that honors the Indigenous heritage while presenting it through a contemporary lens. The meticulous rendering of Ayers Rock and the surrounding natural features reflects the artist's deep respect for the sacredness of these sites, highlighting their spiritual and cultural importance. The interplay of light and shadow, along with the use of vibrant earth tones, evokes the mystical and timeless quality of the Australian outback, bridging the gap between ancient traditions and modern artistic expression. As art critic Jonathan Jones asserts, Andrews' paintings of Ayers Rock "do justice to nature at its wildest in a way that bears comparison with Turner - yet the geology they reveal, under an empty blue sky, is so bizarre it mocks the very act of representing. Andrews does what all the School of London artists in postwar Britain were trained to do: he just paints what he sees. And the result leads us to doubt our own eyes, as the ochre masses of Australia's rocks turn into abstract shapes, coloured stains". In fact, the result can be seen as reminiscent of Dali's surreal landscapes.

Andrews' technique of applying a mixture of acrylic paint and water in a spraygun produced the dreamlike effect of the piece and as Jones notes, this method "removes his direct physical touch from the painting surface. He is not pressing a brush down, not making his mark. The paintings appear to be made passively, in a reverie. They well up out of the light and shadow. Looking at the world from far away, with a mystical scepticism, he sees it as marvellous but not quite real".

Acrylic on canvas - James Hyman Gallery, London, England

Thames Painting: The Estuary

The last painting produced by Andrews in his lifetime (executed while he was undergoing treatment for cancer) was the monumental (over seven feet tall) Thames Painting: The Estuary, which takes the River Thames as its subject. The image depicts an area near to where the artist lived in his final years and it captures the serene, yet dynamic essence of the river. The painting's expansive composition portrays the estuary at low tide, with its vast mudflats, meandering channels, and glistening water surfaces reflecting the sky. Andrews uses a muted palette of blues, grays, and earthy tones to evoke the calm, meditative quality of the scene.

Included in the background of the painting are six silhouetted figures, taken from a Victorian-era photograph. Art critic Alastair Sooke writes that one of these figures "appears to be a ferryman - an allusion, presumably, to Charon, who, in Greek mythology, ferried dead souls to the underworld across the River Styx". This is a powerful piece of imagery given Andrews' need to confront his own mortality during the creation of the piece. The estuary, as a place where river meets sea, also symbolizes transition and fluidity, embodying themes of change, connection, and the passage of time. Andrews' portrayal emphasizes the estuary's role as a living, breathing ecosystem, resonating with his broader environmental and existential concerns.

Curator Richard Calvocoressi asserts that in the painting "Andrews has produced an "extraordinary effect as though the tide has washed over the canvas". Calvocoressi goes on to explain that, to create this effect, Andrews "mixed solutions of turpentine and grit and poured them, from a bucket, on to the canvas, which he had placed on the floor. He then used a hairdryer to blow the liquid about, just like the wind blowing the tide. It's as direct as that: unpainted, almost."

Calvocoressi also notes that "There's no horizon in the painting, so you have this extraordinary sensation of looking down, and across, at the same time. We are engulfed by the thing". Likewise, art critic Matthew Collings writes that "Large areas appear to be playful evocations of the river, close-to and distanced both at once. Your viewpoint might be that of a body drowning or a gull soaring above".

Oil and mixed media on canvas - Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, England

Biography of Michael Andrews

Youth

Michael Andrews was the second child of Thomas Victor Andrews, an employee of Norwich Union Insurance, and Gertrude Emma Green. He was raised in a devout Methodist household and attended the City of Norwich School. During his final year, he took art classes in the evenings and on Saturday mornings, studying oil painting with artist Frank William Leslie Davenport, a member of the Norwich Twenty group of painters.

Education and Early Training

After school, Andrews completed his National service, spending most of the two years in Egypt, where he used his free hours to paint watercolors. Immediately afterwards, he enrolled in the Slade School of Fine Art, where he studied under William Coldstream, William Townsend, Lawrence Gowing, Lucian Freud, and Francis Bacon. His peers and friends included Victor Willing, Keith Sutton, Diana Cumming, Euan Uglow, and Craigie Aitchison.

In 1953, he was awarded a scholarship in painting to the British School at Rome. Here, Andrews befriended Italian film director Lorenza Mazzetti, and painted a portrait of her at the Spanish Steps. Mazzetti then invited Andrews to co-star alongside Eduardo Paolozzi as a feaf character in her film Together (1955), which was shot in London.

Mature Period

In 1959, Andrews' painting A Man Who Suddenly Fell Over (1952), created while he was still a student at Slade, was acquired by the Tate. Calvocoressi notes that this was the beginning of Andrews' "whole interest in human behavior". According to Andrews, the semi-autobiographical painting was about "the complete upsetting of someone's apparently secure equilibrium and about their most immediate efforts at recovery and their attempt to conceal that they have perhaps been badly hurt or upset".

During the 1950s, Andrews became enamored with London's party scene. Though shy and self-conscious, he frequently joined fellow artists Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, and Francis Bacon on social outings at the Colony Room, a private members' club. Arts correspondent Paul Levy explains that "This dingy, smoke-filled, one-room, after-hours Soho drinking club was run by the hard-boiled Muriel Belcher, who, if you were male and she liked you, called you either by a girl's name or by the rudest of all four-letter words". Andrews painted a mural in the club, as well as executing a painting, Colony Room I (1962), which depicted a party scene there.

Andrews' paintings of the next decade or so were similar "party pictures", which curator Richard Calvocoressi describes as "paintings about human beings losing their self-consciousness, losing their inhibitions, [and which] kind of portray society in a state of delirious disintegration". In 1958, Andrews had his first solo exhibition at London's Beaux Arts Gallery (where he had a second show in 1963). That same year, he began teaching at Slade, and at the Chelsea School of Art, though he admitted he did not enjoy teaching. Around this time, he was sharing a studio with Irish painter Patrick Swift.

In 1961, Andrews relocated to his own studio space in London. In 1963, he began living with June Keeley, a woman whom Levy calls "warm" and "pretension-deflating". The two later married, and had one daughter, Melanie, in 1970. Following Andrews' death, Melanie shared warm memories from her childhood, such as her father teaching her to swim in a lake in Scotland. This moment was later turned into a painting by Andrews titled Melanie and Me Swimming (1978-79). Though his party-going days were behind him, Andrews continued to see his School of London artist friends, such as Freud, who would spend Christmas Day with the Andrews family each year, insisting on watching The Wizard of Oz.

Late Period and Death

From around 1970, Andrews' work shifted in tone, as he was increasingly inspired by Zen Buddhism. He stated, "Zen is active meditation (painting in my case) leading to sudden enlightenment which is unself-- or selfless-- consciousness which is realising things just as they are: interdependent. [...] You don't lose individuality or identity by dropping your idea of concept of yourself (your ego) or by acknowledging the fact of interdependence; on the contrary it becomes subtle and unrestricted. That's my understanding anyway." He ceased to paint portraits, and focused instead on landscapes.

While he continued to paint scenes of London and the surrounding areas, art critic John Russell explains that "from 1975 onward, Scotland seized Mr. Andrews's imagination, in part for its stern and often tumultuous history, in part for the austere and geometrical ritual of deer stalking in castle country". Andrews and his wife took their daughter to vacation in Scotland every summer, where they stayed on a friend's estate in Perthshire. Andrews developed an interest in deer hunting, of which he painted several scenes. Calvocoressi notes that in these works, Andrews was concerned primarily with the relationship between man and nature.

In 1978, Andrews relocated to Geldeston on the Norfolk/Suffolk border, before moving to the Norfolk village of Saxlingham Nethergate in 1981. He said of the town "I like the antiquity of it. I was terribly affected by the fact we are living in a 7th-century village (a favourite century of mine)". In 1983, he took a trip to Ayers Rock in Australia, which became the subject of several of his sketches and paintings. In 1988, Andrews served on the Board of Trustees of The National Gallery in London, although he found the journey from Norfolk to be cumbersome, and did not complete his term.

During this period, Andrews moved away from the heavy impasto favored by the School of London artists, instead using a spraygun to apply thin layers of acrylic paint, and even at times leaving parts of the canvas bare. Throughout his career, Andrews shared qualities with his School of London peers, such as his preoccupation with the human form and with landscapes, particularly the relationship between mankind and the natural world. As Moorhouse and Tufnell note, "it was his firm conviction that some sense of the world and our place within it can be formed from reflecting on human nature. [...] Even when people are not physically present in his work - as in his paintings of balloons, fish and certain landscapes - his images are redolent with human significance". Yet, as curator Richard Calvocoressi argues, "in many ways, Andrews was very different from the other painters in the [the School of London]. They were studio-bound artists, painting portraits and claustrophobic interiors. But with Andrews, after a certain date, there are few portraits, and practically no self-portraits. He spent most of the Seventies and Eighties painting big, wide landscapes".

In 1991, Andrews had his first and only New York show, at the Grey Art Gallery of New York University. The following year he moved back to London to a flat in Battersea, near the Thames. The river was the subject of his final work, Thames Painting: The Estuary (1995). Shortly after moving back to London, he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. He underwent surgery in 1994, but died the following year. His funeral was held at St. Mary's Church, Battersea, and he was buried in Perthshire.

The Legacy of Michael Andrews

Compared to his School of London peers, such as Francis Bacon, Leon Kossoff, and Lucian Freud, Andrews and his work was much less well known. Tate director John Rothenstein once stated that he "was in danger of being taken for a rumour rather than a person". This is due, in part, to his shy, even reclusive, personality, and in part because he worked painstakingly slowly, had a relatively low output over the course of his forty-year career, and exhibited infrequently. Nevertheless, as curators Paul Moorhouse and Ben Tufnell recognize, Andrews as "one of Britain's leading post-war painters" whose work "was characterised by intensity of observation and exacting technical virtuosity".

Freud, in fact, saw Andrews' limited production as a positive, once stating that "Andrews is such an economical painter, he only paints masterpieces". Art critic Matthew Collings writes that "The scenes [Andrews] summoned up from lively and exciting surfaces were dreamy and a little weird, like visions: faces, furniture, landscape, decorations, a drunken mood, the London glamour scene. All this but with richly elusive literary associations, too, as if his model of painting was that it should also be a bit like a book". Art critic John Russell asserts that "No living painter was better at taking a well-beaten subject and giving it a whole new spin". Andrews' dreamlike creations and surreal landscapes went on to influence the Magic Realism of artists like Scottish painter Peter Doig.

Influences and Connections

-

![Alberto Giacometti]() Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti -

![Diego Velázquez]() Diego Velázquez

Diego Velázquez - William Coldstream

- William Townsend

-

![Lucian Freud]() Lucian Freud

Lucian Freud -

![Francis Bacon]() Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon - Patrick Swift

-

![Peter Doig]() Peter Doig

Peter Doig -

![Matthew Barney]() Matthew Barney

Matthew Barney -

![Coco Fusco]() Coco Fusco

Coco Fusco ![Karen Finley]() Karen Finley

Karen Finley

-

![Lucian Freud]() Lucian Freud

Lucian Freud -

![Francis Bacon]() Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon - Patrick Swift

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI