Summary of Nobuyoshi Araki

Sex clubs, cats, rope bondage, nude women, and the bliss of newlyweds on a honeymoon are some of the most famous subjects of Nobuyoshi Araki. Probably the most famous and influential Japanese photographer of the post-war period, Araki's work is technically masterful and blurs the lines between high art, photo-biography, and pornography. His photographic practice is controversial, highly sexual, and frequently challenging to both a Western and a Japanese sense of propriety and personal expression.

Araki is known around the world for his prolific output and instantly recognizable brand of immediate and unflinching image-making. Despite this fame and profile, he has nevertheless been arrested for breaching obscenity laws and has been controversial in his working practices. For his detractors, many of his photographs reinforce damaging perceptions of Japanese women (particularly for a Western audience), and yet the artist and his advocates cite him as operating within a tradition of erotic work in Japan that stretches back hundreds of years.

Accomplishments

- Araki's photography is technically masterful whatever its subject, with the same focus, attention, and careful framing he affords a nude body also applied to his cat (Chiro), flowers, or the city of Tokyo and its residents. Subjects are positioned as equally valid signifiers and exemplars of beauty, reimagining hierarchies of what is and isn't important to reflect on aesthetically and drawing attention to the beauty of bodies in both ordinary and extraordinary situations, whether in the streets, sheets, or underground clubs.

- Araki developed an autobiographical mode of working with images that he calls 'I-Photography' (shi-shashin), in which his photography documents his life and the lives of those around him, recording the details and private moments they share. Nothing is off limits as a subject for the camera, with Araki even documenting his wife's deathbed. This way of working is inspired by the 'I-novel' (shi-shōsetsu) which was prevalent in the Japanese literary scene of the early 20th century. This way of working has proven to be inspirational for subsequent generations of biographical photographers who use the medium to explore the beauty and strangeness of their own lives.

- In addition to the quality of his work, Araki also insists on the value of the quantity of images he produces, reflecting his prolific work ethic. Whilst this can make his work difficult to quantify or accurately survey, the sheer volumes of photographs, videos, photobooks, and other material he produces has its own significance, reflecting the depth and centrality of his practice to his life. He suggests that, rather than individual works, it is the spread of images extending throughout his life that is significant, echoing the repeating and never-ending qualities of a Buddhist mandala.

- Araki's work has been legally controversial, with many of his images flaunting Japanese obscenity restrictions on the showing of pubic hair, for example. Despite public outcry, political condemnation, and police interventions, Araki refuses to modify his practice or desist from making his work. This defiance has consistently been positioned as a commentary on Japanese society and a challenge to the hypocrisy of censorship laws and other sexual repression. His practice therefore occupies a unique position where it is recognized as a vastly significant artistic export for contemporary Japan, but also a controversial and occasionally illegal body of work at odds with the establishment.

- Despite the controversy his work has attracted, Araki positions it within a continuum of Japanese art that stretches back to the 17th and 19th centuries. His work has particularly been compared to Ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world), woodblock prints that depict an idealised Japanese society through images of beautiful women and nature. Ukiyo-e also features Shunga erotica, an enduring and more obviously apparent influence on Araki's practice in its depictions of Kinbaku-bi (an ancient form of rope play and bondage). This tension between a very contemporary sexual and social progressiveness and a legacy of tradition is one of the most enduring and unique qualities of Araki's work.

Important Art by Nobuyoshi Araki

Sachin

This black and white photograph from Araki's first series, Sachin, shows the boy of the same name (a charismatic child from Araki's neighborhood of Shitamachi) on his back on the ground, doubled over in laughter as his older brother, Mabo, tickles him. We see only Mabo's right arm extending into the image at the bottom left corner. Other images in the series (which are all black and white) show the two boys aiming slingshots at the camera, play-wrestling, and running around the run-down apartment blocks of the Shitamachi area.

The Sachin series won a Taiyo award for photo reportage. The images convey a sense of nostalgia for childhood, and though the photographs convey no sound, the viewer feels almost as if they can hear the boys' laughter and playful shouts through the images. Said Araki, "I could see my own childhood in the boy called Sachin. I was taking pictures from the point of view of a child." The close attention to the individual subjects of the images, with the camera often close to the action and images taken from a low angle, contrast against the landscape shots and panoramas that had previously dominated representations of Tokyo. As a series, these images show the still-ramshackle nature of life in Tokyo even after the US occupation ended, with a backdrop of poverty offset by the aliveness and energy of the children that are Araki's subject.

Sachin led into another series by Araki, which he called Photographs of Me, for which he set up a makeshift photo studio, and had "regular" people from Tokyo come in to take portraits in rapid succession. The artist believes that in these portraits he conveys who he is through the way he photographs others. This autobiographical sensibility would go on to pervade his entire oeuvre.

Silver gelatin print - Michael Hoppin Gallery, London, England

Untitled

While on honeymoon with his wife and favorite muse, Yoko, in 1971, Araki bought a camera and photographed their entire trip. This image shows Yoko sleeping on a rowboat on the Yanagawa River during their honeymoon. Never one to miss an opportunity to discuss his sex life, Araki explained about the image, "It was our honeymoon so she was exhausted from all the sex." The resulting images became a series titled Sentimental Journey, one of Araki's best-known and most acclaimed works. Araki produced dozens of images, many of which were also published in Araki's 1978 photobook Yoko My Love, intended as an homage to his relationship with Yoko. In 1991, following Yoko's death from ovarian cancer the previous year, the artist published Sentimental Journey / Winter Journey, which presented images from the couple's honeymoon alongside more sorrowful images of Yoko during her illness, and even at her funeral.

This image is one of Araki's favorite photos of Yoko, and features in both Sentimental Journey and Sentimental Journey / Winter Journey. For Araki, it is particularly resonant in the way its composition almost seemed to foretell her coming death. He explained that "In Japan we say that you cross the Sanzu River when you depart to the 'other world'. I had no intention of taking a picture like that, so I feel that maybe God or someone made me take that picture. Her posture is like that of a fetus. Also, in the area where I grew up, we rest the deceased on rush mats. She happened to be sleeping on a rush mat. All by coincidence, it was all there." Despite Araki being most frequently discussed in regard to his erotic/pornographic photo work, his Sentimental Journey is widely considered to be one of the most important Japanese photobooks. Curator Maggie Mustard calls his relationship with Yoko "the nucleus of his most iconic work."

Japanese photography critic and historian Iizawa Kōtarō explains that "Sentimental Journey is structured like a shishōsetsu, or 'I-novel,' sometimes called a 'personal novel,' a Japanese literary form in which the first-person narrator delves deep into the intricacies of personal relationships. [...] The photographs in Sentimental Journey function as the text of an 'I-novel' might, delicately stitching together the story of the artist's relationship with a close other. He would later dub the technique shishashin, rendered in English as 'I-photography' or 'personal photography.' The form went on to become one of the important currents running through Japanese photographic expression." Araki himself asserted, "I believe it is the 'I-novel' that is the very closest artistic form to photography.

Gelatin silver print - Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Untitled from "Tokyo Lucky Hole"

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Japan's sex industry was booming. Araki ventured into sex clubs, private orgies, and other illicit sexual events, and documented the people and scenes he encountered. The image shown here presents a scene in a club in which large holes were cut in coffin-like boxes, allowing male clients below to reach through and fondle the naked females above. It is an uncanny image, with the details of the action obscured by the angle from which it is taken and the positions of its subjects. Toiletries are visible on the right of the image, adding a quotidian dimension to the sexual activity, whilst the pose of the woman suggests boredom or endurance rather than arousal. The male figure within the box is only visible as a disembodied and phallic arm, extending towards her genitals, heightening the strangeness and impersonality of the interaction.

The photobook Araki produced of these images, Tokyo Lucky Hole (1997), was named after one of the popular Tokyo sex clubs that he visited. The images in this series varied significantly, with some showing the exteriors of sex clubs and semi-nude girls waiting in the doorways to entice potential customers, and some showing the graphic sexual acts being carried out inside these establishments, such as intercourse on stages, in beds, and in cages, as well as "glory holes" in action, and more.

Arts and culture writer Alina Cohen asserts that "After viewing Araki's staged portraits, these pictures reveal the photographer as a keen observer of a raucous, apparently joyful community - sex becomes integral to the character of the city itself." Irish Photographer Barry W. Hughes says that Araki's Tokyo Lucky Hole caused his understanding of contemporary photography to "shift" and calls the book a "proverbial punch in the eye" and "a legend". He goes on to assert that "On each visit eyes widen, the pulse fastens and arousal heightens; this is photography as an illicit indulgence and it feels good. With each page too, still more is at hand to provoke through the imagined din of laughter and screams, howls and groans. [...]Tokyo Lucky Hole is a compendium of the grotesque in all it's unfettered, unashamed and gloriously troublesome deviancy."

In February 1985, the Japanese government passed the New Amusement Business Control and Improvement Act, which put an end to many of the sex-entertainment venues Araki photographed for Tokyo Lucky Hole. Thus, the photobook serves as a fascinating historical document of the unique period between 1978 and 1985 when Tokyo's citizens could explore their sexual desires and fantasies more freely. The New Amusement Business Control and Improvement Act of 1985 also affected artistic production, leading to harsh censorship of work by artists like Araki. He spent the next several years fighting against this censorship and was instrumental in getting the government to repeal some aspects of their indecency laws

Gelatin silver print

Bondage

In the middle of his career, Araki produced an extensive series of photographs of bondage, specifically kinbaku, literally "the beauty of tight binding", which was a formal system of ritualistic bondage developed during the Edo period (1603-1867) from a method used for binding criminals and prisoners. In this image the tight ropes restrict and frame the breasts and nipples of the model, who looks across the image and away from the camera. Whilst sexually charged, the image is also aesthetically interesting, with the shadows of the ropes and disturbed clothing further marking the skin of the model and her disheveled hair disrupting the stereotype of an immaculately formal and composed Japanese courtesan. Whilst the woman in the image does not appear to be in pain, her expression is ambiguous, and does not suggest sexual excitement or enthusiastic participation, a factor which complicates the relationship of the viewer to the action represented. This ambiguity is particularly complicated when seen within a context of the excessive sexualization and infantilization of Japanese women that characterizes much pornography.

While Araki's images of bondage are often criticized by Western audiences for perpetuating misogyny and the objectification/fetishization of women, some scholars argue that the images can only be properly understood if read through the cultural lens in which they were produced. For instance, curator Lou Proud sees such images by Araki as a "celebration of women". The artist himself says he wants to "free the women's souls" by tying up their bodies. Indeed, as in this photograph. the women in the images have calm, strong, controlled expression, and do not appear afraid, humiliated, or in pain.

In addition to drawing from the ritualistic, highly structured, kinbaku bondage method, Araki's images of rope-bound women are also influenced by other traditional elements of Japanese art and culture, including traditional Japanese dress, and shunga (Japanese erotic art, usually produced by woodblock print). Araki included plastic dinosaurs in many of the photos, which served as a stand-in for himself within the scene. This may also have been an allusion to the idea of the "lizard brain" (a common term for the brain's limbic cortex), which drives our most primal urges, including sex.

Gelatin silver print - Japigozzi Collection, Geneva, Switzerland

Erotos (Two Girls)

Araki's series Erotos (1993) poetically blends the two major driving forces behind his work, love (with Eros being the ancient Greek personification of love, desire, and passion), and death (Thanatos being the ancient Greek personification of Death). Unsurprisingly, all of the images are highly erotic, with some, including this photograph, presenting explicit scenes of nudity and sexual congress, and others (such as close-up images of blooming or decaying flowers and overripe fruit) alluding more subtly to sex, sexual organs, and death. Extreme close-ups and careful framing to echo or present genitalia are characteristic of Araki's practice during this period, with the side-on purse of a mouth appearing at first glance to be an anus, or an extreme close-up of a vagina placed alongside a raw oyster in its shell, drawing graphic and explicit attention to their similarity in shape and texture.

Erotos (Two Girls) frames two women with intertwined legs in the midst of sex vertically. The camera is an outside observer, watching the action from some distance, as Araki himself would have. Whilst sexual, in the image the heads of the two women are cropped from the frame, adding a strange and unsettling sense of dislocation and remoteness. The two intertwined bodies can therefore be read both erotically and as an image of death. While many viewers consider Araki's juxtaposition of sex and death to border on degeneracy, he has explained that he sees sex and death as the two driving forces behind the beautiful journey of life. Sex generates new life and death is the ending of life, a dichotomy that Araki has explored throughout his career.

Gelatin silver print - Michel Hoppen Gallery, London, England

Untitled from "Tokyo Radiation"

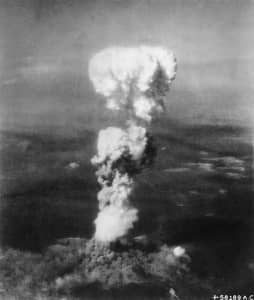

When Araki was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2008, he documented his journey through chemotherapy and surgery in photographs. This image shows his body from groin to chest as he lays on a hospital bed. His pajama top is pulled up to reveal his stomach, surgical scar, and catheter. Other images in the series (which are all shot in black and white) show medical equipment, an empty patio, and other snapshots of his surroundings at the time, documenting the strange dislocation between body and self that is created by medical crises.

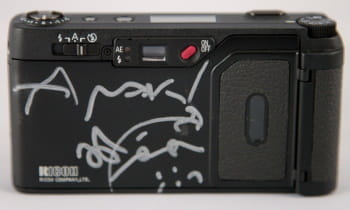

Araki's intention for this series of images, which he titled Tokyo Radiation (2010), was to draw a mental connection between his personal experience of radiation (as a medical treatment for his cancer) and the difficult, collective Japanese memory of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In order to deepen this connection, the artist manipulated the timestamp on his camera in order to mark each photograph as having been taken between August 6-15, the same date that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki occurred on - August 6th and 9th 1945, respectively. Following this bombing Japan surrendered to Allied forces on August 15th.

Arts editor Alice Nicolov emphasizes the fact that Araki "grew up in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing of Japan," and that these events went on to "permeate the photographer's documentation of everyday life". Prior to Tokyo Radiation, he had experimented with the effects of extremely high temperatures on the photographic development process in his 1995 series Shukei (Last Scenery) and his 2003 series ABCD. Exposing these images to high temperatures during development caused them to degrade and warp, as if they too had been victims of radiation.

Gelatin silver print - Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

Biography of Nobuyoshi Araki

Childhood

Nobuyoshi Araki grew up in Shitaya (now Taitō), an older neighborhood of downtown Tokyo. He was first introduced to photography during elementary school by his father, an amateur photographer whose day job was maintaining the family business of making traditional wooden geta clogs. Araki spent much of his childhood playing on the grounds of the Jōkanji temple that was across the street from his house. As Japanese photography critic and historian Iizawa Kōtarō explains, "This was known as a nagekomi-dera (throw-in temple) because during the Edo period (1603-1868) the bodies of prostitutes from the Yoshiwara courtesan district with no family to claim them had been dumped in the temple grounds."

Araki was part of the generation of Japanese who grew up in the years following World War II, when Japan was undergoing major changes as it rebuilt itself following its military defeat by the Allies. This post-war period, during which Japan was occupied by American forces (until 1952) included great social upheavals and economic hardship for much of the population. Many now important Japanese artists and cultural figures came of age alongisde Araki during this time, including photographer Moriyama Daido, artist Yayoi Kusama, actor and filmmaker Takeshi Kitano, and animation director Miyazaki Hayao, with the social changes and new dynamics of society providing a new perspective for many of this generation.

Education and Early Training

From 1959 to 1963, Araki studied film and photography at Chiba University, near his hometown of Tokyo. He disliked the regimented and highly technical approach of the program, which at that time took place within the engineering department. His final film project was titled Children in Apartment Blocks, which he then developed into one of his earliest photo series, Sachin (1964), which won an award from Taiyo magazine.

Araki then worked as a commercial photographer at the Dentsu advertising agency, which he found extremely dull. He did, however, use the Dentsu facilities to further his independent photography work, even using the company's photocopier to produce one of his early photobooks, The Xerox Photo Albums (1970). He held his first solo exhibition in 1965 at Shinjuku Station Building. In 1967, Araki's father passed away. One year later, he met the woman who would become his wife whilst at work at Dentsu - essayist Yōko Aoki. Art historian Matthew Kluk notes that these two events were "pivotal" in Araki's life, writing that "Death and love would become two of the principal driving forces behind Araki's profoundly human photography."

In April of 1970, Araki held an exhibition of enlarged images of his genitals, titled Sur-sentimentalist No. 2: The Truth about Carmen Marie, creating a minor controversy in the Japanese tabloid press and shocking some of the exhibition's audience.

Mature Period

Araki's began a prolific period of work that continued to expand his documentation of his life and muses, including Yoko, who went on to be Araki's most beloved and most photographed subject. The couple married in 1971, and Araki turned his photos of their honeymoon into the photobook Sentimental Journey (1971), which is considered one of the most important Japanese photobooks of the twentieth century. The following year, with Sentimental Journey a great success, Araki left his job at Dentsu and focused exclusively on his art. Araki was incredibly prolific, documenting his life with Yoko, flowers, nature, the city he lived in, and his pets. And, he worked extensively with magazines and models, exploring and documenting his own obsessions and experiences through the multitude of exhibitions, photobooks, and magazine articles he was producing.

This prolific production was accompanied by increasing acknowledgment by the art world and his peers, and he rapidly became a major voice in Japanese photography. In 1974, the same year his daughter Andrea died in an accident, Araki helped to found the Workshop School of Photography along with Japanese photographers Shōmei Tōmatsu and Daido Moriyama. In 1976 he opened the Araki Private Photo School, initially with ten students.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Araki became known for pushing boundaries with his "sex photography", straddling the line between art and pornography. In 1977, Araki began working for the Tokyo magazine New Self and at the same time began publishing two series, Actresses and Pseudo-Reportage for Weekend Super magazine, the precursor to Photo Age magazine. Photo Age and Araki published a series of prankish articles baiting the censorship laws in Japan throughout the 1980s, responding to new legislation by deliberately flaunting it. One article contained images of only pubic hair after the showing of genitals was made illegal, for example, and then, once the display of pubic hair was also made illegal, was followed by a series of images of shaved genitals with pubic hair hand-drawn over the image. In 1988 a series of Araki's contributions to Photo Age were so explicit that Japanese authorities had an entire issue of the magazine recalled and the magazine was eventually forced to close due to escalating legal costs. He also worked for Japanese Playboy during this period, as well as Japanese photography magazine Camera Mainichi.

Araki became better known to an international audience through his participation in Neue Fotografie aus Japan at the Kulturhaus der Stadt, Graz, Austria, in 1977. This major exhibition profiled the wave of new photography emerging from post-war Japan, including work by Araki, Daidō Moriyama, Akihide Tamura, and Yoshihiro Tatsuki. It was a major hit in Austria, attracting large audiences and exposing European art to the new perspectives of artists in the re-emerging global economy of Japan. Whilst Araki's work was recognized as explicit, critics and curators in the US and Europe positioned it as part of a vanguard of new subjectivism in Japanese photography rather than merely pornography, greatly increasing his profile in the international art scene.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Araki documented Japan's underground pornography scene and sex clubs, which had flourished relatively openly during this period. These risqué images of pornographic theatres, orgies, and sex workers were collected and released as a series of photobooks. In 1981, he produced his first film, a "pink film" (a Japanese genre that blends theatrical film with nudity and/or sexual content) titled High School Girl Fake Diary, for the Nikkatsu studio. It was not well-received by either his fanbase or followers of the genre, and the artist subsequently disavowed it, stating his disappointment. In 1992, he was fined 300,000 yen for an "obscene" gallery exhibition, and in 1993, police arrested gallery workers for selling his erotic photobook, Erotos (1993).

Late Period

Araki's beloved wife and muse Yoko died of ovarian cancer on January 27, 1990, the same year he was awarded with Annual Award of the Photographic Society of Japan. Continuing with his photography helped him to cope with this loss. Asian studies scholar Victoire Dufay explains that "Despite his apparent loose morals, Nobuyoshi Araki always proclaimed his real adoration for his wife, who he depicted in numerous photographs. Broken by grief, the photographer produced images tinged with gloom and solitude in the following years. He obsessively photographed Yoko's cat, the inside of his house, flowers and little plastic dinosaurs that he described as his companions." Tragedy struck again in 1994, when Araki's son Pablo died after a long illness.

In 1992, Araki met Swiss photographer and documentary filmmaker Robert Frank who was visiting Japan. The two artists bonded over their use of the camera to work through the process of grief. The same year, Araki held his first international solo exhibition, Akt-Tokyo: Nobuyoshi Araki 1971-1991 at the Forum Stadtpark, Graz, Austria, and also published Sentimental Journey / Winter Journey 1972-1992, which documented his relationship with his wife, from their early days of blissful young love to the challenging later years when she was struggling with her illness.

In 2008, Araki was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Surgery to remove the cancer was successful. In 2010 another muse, his beloved cat Chiro, died of old age. In October 2013, a retinal artery obstruction caused the artist to lose vision in his right eye, leading him to develop an exhibition titled Love on the Left Eye, held at the Taka Ishii Gallery in Tokyo in 2014, featuring photos whose right half had been blacked out. In recent years, he has worked with celebrities, shooting Björk and Lady Gaga, as well as for Italian luxury label Bottega Veneta. He continues to work voraciously. Björk recently stated, "he's the most energetic person I know [...] an artist like Araki is going to do everything at 9000 percent".

Over the past decade, Araki has been at the center of controversy regarding alleged sexual misconduct with former models, such as model Kaori, who in April 2018, wrote that while working with Araki between 2001 and 2016, she "worked without a contract, was forced to take part in explicit shoots in front of strangers, was not regularly paid and that her nude images were often used without her consent", leaving her severely traumatized by the experience. In solidarity with Kaori, and another model who came forward accusing Araki of inappropriately touching her, the activist group Angry Asian Girls Association protested the opening of an Araki exhibition in Berlin in December 2018.

The Legacy of Nobuyoshi Araki

Araki is widely regarded as one of the most significant post-war Japanese artists. Certainly within the field of photography, he has achieved a high level of recognition, despite the controversial subjects of his images. Art historian Matthew Kluk calls Araki "one of the most prolific figures in the field of Japanese photography", whilst David Frazier similarly cites him as "Japan's most important living photographer". Kluk suggests that "the frenetic nature of his photographs, which he tends to shoot with very little preparation, is emblematic of the Japanese experience of World War II and its chaotic aftermath."

Araki has produced an extensive and extremely varied body of work (including over 500 photobooks), which has influenced subsequent photographers in nearly all genres, including street photography, documentary photography, portraiture, erotic photography, and more. According to curator Maggie Mustard, he influenced fashion photography in regard to "this aesthetic of the candid, the hip shot, the emphasis on the explicit." Arts and culture writer Alina Cohen notes that Araki's "aesthetic is instantly recognizable, whether he's capturing submissive, rope-bound women, grungy group sex in Tokyo, or eroticized flowers. [...] Over the years, Araki has become a brand." Arts editor Alice Nicolov praises his "innate technical mastery of image staging and colour."

The work of American photographer Nan Goldin is often compared with that of Araki. After meeting in 1992, Goldin stated "I'd already heard about this wild man of Japanese photography and of his diaristic, intensely sexual work. [...] I was astounded to find a man on the other side of the planet who was working the same obsessions I was." They went on to do a number of artistic collaborations, most notably the photobook Tokyo Love: Spring 1994. Araki has also had a significant influence on younger Japanese photographers, such as Daifu Motoyuki whose 2014 photobook Project Family carries on Araki's "I-photography" approach, and Momo Okabe, who, like Araki in his younger days created a handmade photobook to present her sexually explicit photographs.

Araki's greatest legacy, however, may be the heated debates his career has sparked regarding the boundary between art and pornography. As Nicolov explains, "The endless question surrounding Araki's work is whether it's art, a brilliant masterpiece, a fantastic form of conceptual photography or misogynistic, gratuitous porn. [...] Maybe you see Araki as a dirty, lecherous old man living out his sexual deviancies by undressing and binding his models or maybe you see him as a Tensai (a master) who uses his camera to capture unimaginably intimate and shocking images as part of a huge body of work. Your choice." Even a positive review from art critic Taki Koji mentioned the "raping gaze" present in Araki's voyeuristic style. Yet some scholars, like curator Lou Proud, see Araki's work as "a celebration of women" rather than as misogynistic.

Influences and Connections

- Cari Theodor Dreyer

- Robert Bresson

-

![Robert Frank]() Robert Frank

Robert Frank - Daido Moriyama

- Keith Wong

- Shōmei Tōmatsu

-

![Street Photography]() Street Photography

Street Photography -

![Fashion Photography]() Fashion Photography

Fashion Photography -

![Documentary Photography]() Documentary Photography

Documentary Photography - Italian Neo-Realist Film

- French Nouvelle Vague Film

- Ren Hang

- Daifu Motoyuki

- Momo Okabe

-

![Robert Frank]() Robert Frank

Robert Frank - Daido Moriyama

- Keith Wong

- Shōmei Tōmatsu

Useful Resources on Nobuyoshi Araki

- Nobuyoshi Araki - Sentimental Journey 1971-2017Our PickBy Hiromi Kitazawa

- Nobuyoshi Araki: Self, Life, DeathOur PickBy Akiko Miki, Yoshiko Isshiki, and Tomoko Sato

- Araki. 40th Ed.

- Nobuyoshi Araki: Tokyo Novelle

- Nobuyoshi Araki, Hi-Nikki (Non-Diary Diary)

- Araki by Araki: The Photographer's Personal SelectionOur Pick

- Nobuyoshi Araki: Photo-Theater: Tokyo Elegy

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI