Summary of Max Bill

Max Bill was one of the last great polymaths of European modernism, working across fields from painting to design to architecture. The style which he helped to define, Concrete Art, was one of the most influential movements in mid-century art, rooted in rationalism, efficiency of means and materials, and an unyielding emphasis on abstraction. Within graphic and commercial design, meanwhile, Bill helped to codify the sleek minimalism which defined the middle decades of the century, and his architectural projects were similarly influential on the post-war renaissance of modernism influenced by Le Corbusier and The International Style. As a teacher and critic he represented the enduring legacy of the Bauhaus, establishing a similarly influential design school at Ulm.

Accomplishments

- Max Bill did more than any other figure in modern art to establish the identity of Concrete Art. Rooted in Constructivism and De Stijl, Concrete Art proffered a stylish, geometrical minimalism (using precisely defined shapes and lines) with no representational aspect, often representing mathematical formulae in visual terms. Concrete Art, and therefore Bill, influenced many subsequent art movements, including Kinetic Art and Hard-Edged Painting.

- Max Bill was the co-founder and, from 1950, the first principal of the Ulm School of Design in West Germany. This hugely influential institution was seen as a successor to the Bauhaus, updating its emphasis on functional creativity with new ideas such as semiotics and modular building techniques. Through his close association with the Ulm School, Bill became an enormously consequential figure within mid-century European art and culture generally.

- Bill was amongst the last of a generation of modernist artists who worked across a wide range of media with seeming ease. Initially training as a silversmith, he remained active in commercial design throughout his life alongside his work in painting and sculpture, as well as being an architect and an influential critic and teacher. The ideas underpinning Bill's Concrete Art emphasized a problem-solving role for the artist in relation to society, perhaps leading him to take on this wide range of personae.

- Bill was, perhaps surprisingly, extremely influential on the development of modern art in South America, despite never living there and having no biographical connection to the continent. After his work was featured in the first São Paulo Biennale of 1951, he inspired generations of Concrete Artists in Brazil, Argentina and beyond. This led to Latin America becoming the primary center of the Concrete Art movement and also influenced the emergence of Neo-Concretism in the late 1950s.

The Life of Max Bill

A true twentieth-century Renaissance Man, Max Bill was educated by luminaries of early-twentieth-century modernism such as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, and Le Corbusier.

Important Art by Max Bill

Construction

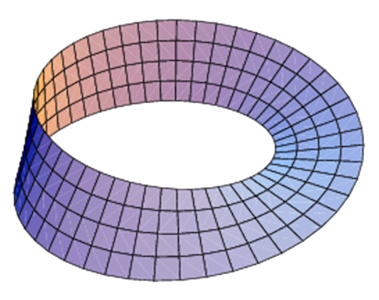

Construction (1937) is a masterful demonstration of Max Bill's commitment to geometric abstraction and the principles of what would later be known as Concrete Art. Its form is a continuous loop, intricately interwoven to create a sense of fluidity and motion, despite the rigidity of the grey granite. The shape exemplifies Bill's exploration of mathematical forms in art, by which he sought to translate abstract concepts into tangible, visually engaging structures.

The piece is based on the form of a torus (a geometrical form similar in appearance to a donut). That shape has been bisected and reassembled into two rotated forms, with their smooth, polished surfaces gracefully balanced along an axis. The design invokes sacred geometry, as the torus symbolizes the rotational solid of a sphere, and its planar top reveals two perfect circles. That fundamental shape, first seen in this 1937 sculpture, gives an early indication of how Bill would work throughout his career, creating multiple variations on a single geometric theme.

Bill's use of a Möbius strip-like form challenged traditional notions of sculpture by introducing a continuous surface that defies conventional spatial logic. This innovation has been noted by critics and curators as a pivotal moment in the evolution of abstract art. The construction process involved assiduous planning and execution, requiring not only artistic vision but also technical skill to manipulate the granite into an intricate and balanced form.

Grey granite

Four Constructions on the Same Theme

In Four Constructions on the Same Theme, Bill developed a series inspired by a spiral movement that transitions through geometric shapes: from a triangle to a square, then to a pentagon, an octagon, and back again. In this sequence, the third side of the triangle extends to form one side of the square, resulting in an incomplete triangle and creating a continuous spiral of straight lines, each of equal length. Within the confines of strict limitations and a palette of prismatic colors alongside black, grey, and white, Bill crafted fifteen precise variations on this geometric theme.

This work is an exploration of geometric abstraction and color theory. It is constructed from a background glass painting with two reliefs, showcasing Bill's meticulous approach to form and structure. It exemplifies his belief in the integration of mathematical precision with artistic expression, using simple geometric shapes to create complex visual rhythms and harmonies. As Bill wrote, "concrete art is the pure expression of harmonious measure and law. It organizes systems and gives life to these arrangements by means of art. It is real and spiritual; non-naturalistic while close to nature. It aspires to the universal yet cultivates the unique; it suppresses individuality in favor of the individual."

Background glass painting with two reliefs - Zurich Art Museum

Haus Bill (also known as Casa Villiger or the Villiger House)

Haus Bill is a residential home and artist's studio located in Zumikon, near Zurich. Spanning approximately three hectares and bordering a nature conservation area, the property exemplifies Bill's classic style as an architect. In particular, the house reflects Bill's economy of means to achieve stylish, modernist-minimalist results.

During the 1940s, architectural commissions were scarce and heavily restricted, due to the use of cement and steel for defense purposes. Despite these limitations, Bill, with his experience in prefabricated systems, received a commission to build a small private house in the countryside. He was permitted to use only a minimal amount of cement for the foundations, so designed a skeletal wooden structure with exterior walls made from prefabricated Durisol sheets. Durisol was a type of construction panel made from a composite of wood fiber bonded with cement which was highly durable and insulating. Bill's use of Durisol panels was part of a broader movement towards energy-efficient prefabricated housing design in Switzerland, which became very important in the late 1940s in addressing post-war housing shortages.

Bill's choice of materials not only made the construction process more efficient but also demonstrated a commitment to functionalism and simplicity, core principles which he had inherited from the Bauhaus and would later apply at Ulm. The design thus emphasizes clean lines, open spaces, and seamless integration with the surrounding landscape. The Bill Haus can be seen, in short, as a practical application of Bill's belief in the social responsibility of design, aiming to provide affordable, well-designed housing.

Durisol concrete blocks and timber frames - Bremgarten, Switzerland

Ulm Stool (Early example used at the Ulm School of Design)

The Ulm Stool is one of Max Bill's most celebrated works, epitomizing the sleek, minimalist style of mid-twentieth-century design. Crafted from three planks of untreated natural spruce wood and a lateral wooden bar, this iconic piece of furniture embodies simplicity and elegance, designed to be lightweight yet sturdy. Its versatility allows it to function not only as a stool but also as a small table, or even a carrying container.

For Bill, functional design was to be a crucial aspect of post-war economic recovery in Northern Europe. In order to maximize efficient use of materials, the design of objects for domestic, industrial, and commercial use would have to be increasingly practical, pragmatic, and minimalistic. At the same time, there was an increasing emphasis on the aesthetics of functional objects at this time, inspired by the new consumer culture of the USA. For the first time, products, often mass-produced in a factory, could be prominently featured in magazines for their artistic beauty. It was in this context that Bill propagated his existing approach as a designer.

In terms of its specific application, the Ulm Stool was created in collaboration with Indonesian-German industrial designer Hans Gugelot in order to meet the furniture needs of the Ulm School of Design, the school that Bill had cofounded in 1950. Resources at the school were limited, therefore, according to the HfG-Archiv Ulm, the stool embodies the school's ethos of achieving maximum functionality with minimal means. More generally, it is a tangible manifestation of Bill's belief that design should seamlessly integrate functionality with aesthetic appeal. The work stands as an icon of mid-20th-century design.

Wood and dowels - Originally designed for the Ulm School of Design

Endless Ribbon

Bill's Unendliche Schleife (Endless Ribbon) series was created from the mid-1930s until the mid-1990s, consisting of an ongoing series of public sculptures, many in civic and urban spaces, based on the form of the Mobius strip. Because of the sheer scale of this sequence of works and the fact that many are widely publicly visible, these works are amongst the artist's best-known.

In this example, made from bronze, the smooth, reflective surface of the material enhances the sense of movement and elegance in the design, guiding the viewer's eye along its edges. The design itself is of course inspired by the geometric shape discovered by the nineteenth-century German mathematician A.F. Möbius, a loop made up of a single surface, with "top" and "bottom" merging seamlessly into each other. In deploying this single, continuous surface to create a sculptural form, Bill was responding to the new physics of the twentieth century - ideas such as time-space relativity - which challenged traditional understandings of space and solid form.

Displayed at the open-air museum of sculpture in Middelheim, Antwerp, this piece is amongst many widely viewed iterations of the Endless Ribbon series. Other, similar works can be seen at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Pompidou Center in Paris, and the Louisiana Art Museum in Denmark. The series as a whole stands as testament to Bill's fascination with translating complex mathematical concepts into visually compelling art.

Bronze - Open-air museum of sculpture Middelheim, Antwerp

Pavillon Sculpture

Composed of 23 identical granite blocks, each measuring 42 x 42 x 210 cm, the Pavillon Sculpture forms an inviting walk-in pavilion, with pillars and arches that viewers are able to walk under and through. Its dynamic appearance, varying with the viewing angle, underscores Bill's mastery in creating works that invite continuous exploration and interaction. Meanwhile, the use of identical components to create a varied whole is comparable to his earlier exercises in methodical alteration of a single geometrical form. The granite, sourced from a long-closed quarry in the Black Forest, grants historical significance as well as material heft to the work.

According to the City of Zurich, the artwork is a key piece from Bill's later period and exemplifies the ideals of the Zurich School of Concrete Art. That school, rooted in Bill's 1930s-40s collaboration with artists such as Richard Paul Lohse and Leo Leuppi, emphasized pure abstraction and the use of geometric forms, moving away from any basis in organic form or representation of an external object.

The Pavillon Sculpture is not only important for its formal qualities, however. It also represents Bill's vision of integrating art into daily life and public spaces, thereby reinforcing the social function of art. The sculpture has been praised for its transformative impact on the urban landscape. Situated on the bustling Bahnhofstrasse, it offers a space of tranquility and contemplation amidst the city's hustle and bustle.

Granite - Zürich, Switzerland

Biography of Max Bill

Childhood

Max Bill was born in the small town of Winterthur in eastern Switzerland, near Zurich, in 1908. He lived with his parents and brothers in an apartment directly above the tracks of the railway station, where his father was deputy station manager. Understandably, Bill's earliest drawings were of trains. As a child during the First World War, he also observed the transportation of injured soldiers in troop trains across Switzerland. Later in life, he vividly recalled the whimpering of the wounded, and how his mother would offer them fruit juice through the train windows.

Bill's mother, originally from the small Swiss town of Brugg, had a natural talent for teaching, nurturing her sons' creative and intellectual pursuits with skill and patience. The artist's grandfather, a colonel in the Swiss army, would sometimes take him on tours of Brugg, showing him various military bridges and explaining their modes of construction. Although Bill was initially unimpressed by the military themes of these talks, he later developed a keen interest in the technical aspects of bridge-building.

Two of Bill's uncles, Adolf Weibel and Ernst Geiger, were moderately successful landscape painters, part of the Swiss generation influenced by the Impressionist Giovanni Giacometti and the Expressionist Cuno Amiet (two figures seen as spearheading modern art in the country). Ernst, who studied medicine, forestry, and natural sciences before taking up painting as a side-interest, became young Max's favorite uncle and a role-model. It was at this time that he developed an abiding desire to be a painter.

Art was an integral part of life in Bill's parents' home. In 1918, his father took him to an exhibition of self-portraits by contemporary Swiss artists in Winterthur. It was there, at the age of nine, that Bill encountered painting in the new, modern style influenced by the Swiss Realist and later Symbolist Ferdinand Hodler. However, he was unaware of the hugely influential Dada movement that had begun two years earlier at the Cabaret Voltaire performance space in Zurich, opened by Hugo Ball. Later, Bill's work would stand for a model of control and rationalism in abstract art that was in many ways the counterpoint to the enduring spirit of the Zurich Dada.

Early Training and Work

Max Bill initially aspired to become a geologist, but his academic performance was not seen to meet the required standards. Indeed, university education per se was not an option for him, but his desire to paint was unwavering, and would remain so throughout his life. His father insisted that he learned a trade, so Bill chose silversmithing, an art-form with historical roots dating back to the Middle Ages.

In 1924, therefore, at the age of 16, Bill enrolled in the School of Applied Arts in Zurich. The school's director, Alfred Altherr, was a highly progressive and influential figure. Besides his role at the school, Altherr directed the Museum of Applied Arts and was the founder and president of the Swiss Werkbund. Under his guidance, Bill developed a love for his subject, although silversmithing had initially been a choice made partly under parental guidance. The museum's exhibitions, organized around fundamental themes such as "the form without decoration" and "the chair," also left a significant impression on the budding theorist and critic in him.

After completing his apprenticeship as a silversmith in Zurich during 1924-27, Bill made the hugely consequential decision to take up studies at the Bauhaus, then based in Dessau, Germany. Initially associated partly with Expressionism, the Bauhaus had developed to become the primary school for Constructivist aesthetics and teaching methods in Europe, and one of the key centers of modern art in Europe as a whole. "I can still remember that very morning," he later reminisced, "just before I arrived at the railway station in Dessau, the facade of the Bauhaus building suddenly appearing opposite. There was nothing else like it: striking white walls and large dark glass facades and, in the foreground, the students' house with balconies and red-lead doors. Sensational!"

As a student during 1927-29, Bill was profoundly influenced by the now-legendary Bauhaus faculty, including the painters Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Josef Albers, the sculptor and designer Oskar Schlemmer, the pioneer of abstract photography László Moholy-Nagy, and the master of modern architecture Walter Gropius. Bill's time at the school was highly productive, not only influencing his future artistic sensibilities but also giving him a grounding in the social and philosophical issues wrapped up in the study of modern art.

In addition to essential courses, Bill took optional "free painting" classes with Klee and Kandinsky. He was particularly influenced by Klee, with whom he conversed in Swiss-German. Bill later recalled that he only grasped the value of Klee's famous, intuitive and experimental learning methods - published in English as Pedagogical Sketchbook [1968] - several years aftewards. According to his son, Bill mounted his early watercolors, like Klee, on passe-partouts (a mounting technique involving placing artwork on a thick piece of paper or cardboard with an opening cut in the center) and signed them in Klee-style handwriting.

Bill also maintained a long association with Josef Albers, later seen as a key figure in the Concrete Art movement which Bill himself would pioneer. Albers taught his student not only about painting, but about the wider creative and socially committed relationship that artists and designers should develop with their physical environment. This was influential on Bill's later approach to art, which was rooted in the idea that creative actions needed logical motives and reasoning. This concept is at the heart of Concrete Art.

Bill left the Bauhaus after two years and returned to Switzerland, probably because he was unable to pay his student fees. The rise of fascism in Germany led to the closure of the school under ideological pressure in 1933, after it had briefly relocated to Berlin in 1932. Many of the key figures fled to other European countries or to North America. Switzerland would remain neutral during the ensuing years of tumult, just as it had during the First World War, allowing Bill to remain in his home country across the 1930s-40s.

Mature Period

After a brief relationship with the French performance artist Nusch Éluard (later married to the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard), Bill married Binia Mathilde Spoerri, a cellist and photographer, in January 1931. Across the 1930s, Bill earned his living primarily through working as a graphic designer and typographer in advertising and publishing. He collaborated with Binia, herself a notable artist, on several commercial projects.

He continued to work as a painter and sculptor, developing the minimalist, rational style that would later be described as Concrete Art, involving a small number of colours, shapes and lines arranged in logical, predetermined sequences. In 1937, Bill formed the Allianz group to promote Concrete Art, along with the artists Richard Paul Lohse and Leo Leuppi. The group held its first show in Basel that year, and subsequent exhibitions were mounted across Switzerland during the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Although, by the late 1930s, Bill aspired to work as an architect, he was offered no major commissions before the Second World War. However, he had acquired contacts amongst the young architects associated with the so-called New Objectivity (a minimalist modern style, mostly concerned with painting, that had roots in Constructivism, and which had influenced the design of the Bauhaus Dessau). They offered him work on elements of architectural projects, including signage for the shopping and business center in Zurich known as the Zett-Haus (Z-House). Bill also began creating sculptures during this period, including the Lange Plastik (Long Sculpture) (1933) and the earliest iteration of his Unendliche Schleife (Endless Ribbon or Mobius strip) design (1935). He took charge of designing an anti-fascist magazine in Zurich, which featured the works of Italian anti-fascist novelist Ignazio Silone and Swiss art-historian Georg Schmidt, a member of the Basel-based anti-nazi art collective Gruppe 33.

In 1943, Max and Binia had a son, Jakob, later a scholar and artist. In 1944, Bill began teaching at the Zurich Kunstgewerbeschule. After the culturally fallow years of the war, he began to gain recognition for his work across painting, sculpture, design, and architecture during the late 1940s. In 1950, he became the first principal of the Ulm School of Design (in German, the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, or HfG). This school was widely seen as a successor institute to the Bauhaus, and was strongly influenced by anti-fascist ideology, having grown out of a school of adult education founded by Inge-Aicher Scholl, sister of the White Rose Movement leaders Hans and Sophie Scholl, who were executed for protesting against the Nazi regime. The Ulm School of Design offered courses in art, writing, graphic and commercial design architecture, and more, updating the Bauhaus's pedagogical approach to take in new theoretical and technological developments such as semiotics, information theory, and modular building techniques.

Bill's aim at the school was to apply the progressive and humane principles that had steered the Bauhaus to post-war German reconstruction, an effort supported by the USA's Marshall Plan, which was pumping huge amounts of money into Europe to facilitate its regeneration, in return for greater market access for American goods and services. A true founding spirit, Bill even designed Ulm School's campus, as well as serving as rector, tutor, and head of the architecture department.

The Ulm School attracted students and faculty from around the world, becoming the most important design school in post-war Europe. Its philosophy - that no aspect or object of modern life could not be redesigned in a more rational, practical, and beautiful ways - became hugely influential. It also reflected the ethos of Bill himself, who, as well as remaining a practicing painter and sculptor, designed everything from electrical plugs, clocks, stools, and watches to multi-story buildings during his time at Ulm. His connection to the school ensured his legacy within various schools of modern design.

As an architect, Bill's uber-rational, minimalist approach was becoming widely fashionable and influential, part of the second wave of modernist architecture that was sweeping across Europe and Latin America at this time. His Ulm Campus embodied this approach, which underpinned many of the new civic and social housing and town-planning projects of the post-war decades, as older, nineteenth-century urban dwellings were cleared and new estates and towns, often on the outskirts of cities, sprung up.

Late Period

Various personal and political conflicts led to Bill's resignation from the Ulm School in 1956. However, by this point, Bill had by established himself as an internationally respected artist, designer, and architect. In particular, his influence on Latin American art and culture was huge.

The reasons for Bill's great popularity in South America are various. In 1951, he participated in the inaugural São Paulo Biennale in Brazil, winning the grand prize for sculpture. This event was pivotal, introducing his ideas to a wide audience on the continent. In a wider sense, Bill's rational and logical approach to art and design resonated with the region's burgeoning modern art movement. This was rooted partly in the desire to create strong national cultural identities as countries such as Brazil emerged from the privations of war and the longer shadow of European rule.

South America already had a burgeoning Concrete Art movement, connected to groups such as the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invencíon, founded in Buenos Aires in 1944 by Tomás Maldonano, later a student and tutor at Ulm. But after Bill's reception on the continent, the movement expanded and flourished. In Brazil, artists such as Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark drew inspiration from Bill's approach to form and space, integrating these concepts into their pioneering works. Likewise, in Argentina, artists like Raúl Lozza and Alfredo Hlito adopted Bill's principles, which significantly shaped their approach to geometric abstraction. Indeed, it was largely in Latin America rather than Europe that the term "Concrete Art" became widely used. In the mid-1950s, the Concrete Poetry movement was founded by the Noigandres poetry group, based in São Paulo, and the Swiss poet Eugen Gomringer, Bill's secretary at Ulm. This was another significant development in mid-twentieth century art connected to Bill's influence in South America.

During the 1960s-70s, Bill worked on ever-more prestigious and large-scale sculpture, design, and architecture commissions. In particular, his ongoing Endless Ribbon series of sculptures, inspired by the Möbius strip, appeared in more and more public spaces across Switzerland and Germany. Notable architectural projects included the pavilion for the Swiss National Exhibition in Lausanne in 1964. Bill continued producing studio artworks and his international presence as a painter grew. Major worldwide exhibitions during this time included the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1974). His poster design for the 1972 Munich Olympics became an iconic work of stylish commercial art.

Bill also dedicated himself to education, offering lectures and publishing essays. And he became an influential critic through his writing and speaking on design, architecture, and industrial technology. A committed anti-fascist throughout his life, he became involved in politics, serving on the Zurich City Council and the Swiss National Assembly across these decades.

Bill's cool, rational style continued to attract praise and acquire prestige even during the 1980s, when a shift to Neo-Expressionism and more gestural styles of painting was taking place. A major international exhibition of his work was held at Kunsthaus Zürich in 1988. He continued to work tirelessly until his death on December 9, 1994, following a heart attack at Berlin Tegel Airport.

In 1974, Bill had begun a relationship with the art historian Angela Thomas, when she was 26 and he was 66. They lived together for many years before marrying in 1991. Angela endeavored to support his work and legacy after his death, founding the Max Bill Georges Vantongerloo Foundation to ensure that Bill's contributions to art and design remain recognized and appreciated.

The Legacy of Max Bill

According to his son, the artists and critic Jakob Bill, Max Bill "was a multi-talented man," just like "the medieval concept of homo universalis. He was regularly informed about what was going on in all those fields and he never took any vacation; it was as if, by going from one area of interest into another, he regenerated himself. It filled him with energy again and again every time he turned to something different."

Renowned in the fields of applied arts and design, Max Bill stands out as a leading figure in Concrete Art. Art historian Yve-Alain Bois describes Bill as "the supreme heir of the prewar tradition of (European) geometric abstract art." As a co-founder of the Ulm School of Design, Bill played a crucial role in shaping the post-war design education landscape. Bill's emphasis on applying Bauhaus principles to real-world problems and his dedication to functionalism and simplicity have left an enduring mark on the field. His work seamlessly integrated mathematical precision with aesthetic beauty, demonstrating that art and design could be both practical and visually compelling.

Bill directly influenced a whole generation of artists and designers, particularly within the Concrete Art and Neo-Concrete movements. In Latin America, his impact was particularly significant, inspiring artists such as Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, and Hélio Oiticica with his emphasis on clarity, structure, and the elimination of unnecessary elements. These artists adopted Bill's ideas of pure abstraction and integrated them into their work, much of which is now even better-known than Bill's. Through Concrete Art, moreover, Bill's work had an impact on all the subsequent movements in modern art influenced by the Concrete Artists' technological and minimalistic tendencies, including Kinetic Art, Hard-Edged Painting, and more.

Influences and Connections

-

![Josef Albers]() Josef Albers

Josef Albers -

![László Moholy-Nagy]() László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy ![Georges Vantongerloo]() Georges Vantongerloo

Georges Vantongerloo- Richard Paul Lohse

- Leo Leuppi

-

![Lygia Clark]() Lygia Clark

Lygia Clark - Franz Weissmann

- Lygia Pape

- Hélio Oiticica

- Ivan Serpa

- Amílcar de Castro

- Waldemar Cordeiro

-

![Concrete Art]() Concrete Art

Concrete Art -

![Kinetic Art]() Kinetic Art

Kinetic Art -

![Op Art]() Op Art

Op Art ![Neo-Concrete Art]() Neo-Concrete Art

Neo-Concrete Art- Mid-century Modernism

Useful Resources on Max Bill

- Constructive Clarity: Max Bill and His Time, 1940-1952Our PickBy Max Bill, Fiona Elliott, Angela Thomas

- A Subversive Gleam: Max Bill and His Time: 1908-1939Our PickBy Angela Thomas Schmid, Max Bill, et al.

- Max BillBy Manuel de Junco, Max Bill, et al.

- Max Bill: No Beginning, No EndBy Angela Thomas Schmid, et al.

- Circle! Square! Progress!: Zurich's Concrete Avant-garde. Max Bill, Camille Graeser, Verena Loewensberg, Richard Paul Lohse and Their TimesBy Thomas Haemmerli, Brigitte Ulmer

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI