Summary of Mark Bradford

Los Angeles-born Mark Bradford is an acclaimed visual artist known for his innovative use of mixed media and his engagement with social and political issues. Growing up in a racially shifting neighborhood and later working in his mother's hair salon, Bradford developed a deep understanding of urban life and cultural identity, themes central to his work. Shy, Black, gay, and exceptionally tall, Bradford faced early experiences of marginalization that shaped his perspective and artistic voice. Although he began his formal art training later in life, he has honed a practice that blends abstraction with social commentary, which has earned him international acclaim as one of the most important artists of his generation.

Accomplishments

- Bradford's breakthrough came in the early 2000s with his use of end papers - thin sheets used in hairdressing - which he layered and sanded to create complex, textured surfaces. This evolved to his signature use of excavated and recontextualized signs, flyers, posters, and other paper ephemera of his life in the city and his surrounding environments - layered, scoured, and removed to give the visual and textural effects of actual painting.

- Although typically abstract in appearance, Bradford's work consistently examines underlying themes of displacement, survival, and resilience within the Black community he grew up in, and continues to work within, offering a deeply personal perspective on historical and contemporary social issues such as the LA Migration of the West Adams neighborhood, the AIDS epidemic, and the Rodney King Riots.

- Bradford's contributions extend beyond the art world, as he has reinvested many of the fruits of his success back into the communities that fostered him, most empathically through Art + Practice, a nonprofit blending art and social services which he co-founded with his partner Allan DiCastro.

The Life of Mark Bradford

Black, gay, exceptionally tall, Mark Bradford was naturally shy as a child. However, these very qualities became the foundation of his artistic identity. Inspired from experiences in his mother's hair salon and extensive reading, Bradford's mixed-media and conceptual works serve as powerful representation of racial struggles, enriched with reflective depth.

Important Art by Mark Bradford

Death Drop, 1973

Death Drop (1973) was created by Mark Bradford when he was twelve years old. The footage, shot on Super 8 film, captures a young Bradford performing a dramatic fall. With his mouth open and arms outstretched, he appears to have been struck down, collapsing as though by a violent force. Yet, in his ascent, he seems to rise in a moment of resurrection, as if reaching toward the heavens. In a perpetual state of ecstatic uncertainty, Bradford's body oscillates between death and transcendence, confronting its own mortality only to rise above it.

Bradford explains, "When I started to go through puberty, the body that I was born into started to grow to be six-foot-five at 12. I was just this shy little weird kid, which I was completely fine with, but now you have all these debates around your body and disappointment." He adds, alluding to his burgeoning queerness, "And I'm just 12 years old trying to have a good time, but having to navigate people's perceptions of me, it's just constant object-subject."

This early work was featured in Bradford's 2023 exhibition You Don't Have to Tell Me Twice at Hauser & Wirth in New York, serving as a poignant self-portrait that delves into themes of vulnerability and resilience. Its autobiographical nature offers insight into Bradford's early engagement with performance and his exploration of personal identity.

The piece acts as a precursor to his later work, Death Drop (2023), a larger-than-life sculpture depicting the artist in the iconic "death drop" pose from gay ballroom culture. Bradford has expressed that he wanted the sculpture to be performative yet address persecution, noting, "That's why this sculpture has a puffer jacket - he's outside. It's not in a space of protection, which would be the club." By juxtaposing these two works, Bradford creates a dialogue between his past and present selves, highlighting the enduring impact of societal pressures and the quest for self-acceptance.

Single-channel video, no audio, 20 second loop - Hauser & Wirth, New York

Burn Baby Burn

Burn Baby Burn exemplifies Bradford's innovative use of mixed media to redefine abstraction. The artwork features a densely layered composition of geometric shapes, primarily rectangular and square, which seem to float across the surface. These forms were created using fragments of paper and other materials, adhered to the canvas and then manipulated through techniques such as sanding, scraping, and eroding. The color palette is predominantly neutral, with shades of beige, white, and gray, punctuated by vibrant accents of neon orange and yellow, creating visual tension.

The work reflects Bradford's re-contextualization of found materials from city environments, such as merchant posters and billboards. In Burn Baby Burn, the overlapping shapes and text embedded within the composition allude to the fragmented narratives and experiences of modern life. The title, evocative of the 1965 Watts riots, situates the work within a socio-political frame, hinting at the racial and cultural tensions that underlie much of Bradford's art. Through this work, he bridges the gap between the personal and the collective, creating a dialogue about the impact of socioeconomic and cultural dynamics on individual lives and communities.

Mixed media on canvas - Private collection

Big Daddy

Bradford's Big Daddy was part of the Can You Feel It? series, demonstrating the artist's ability to blend personal narrative with broader cultural critique. The work is presented in a triptych format, featuring repeated images of a young child's face - possibly a reflection of Bradford's own memories or a representation of collective identity. Each panel incorporates hand-written words, such as "Big Daddy," "mijo" (a Spanish term of endearment derived from "mi hijo," meaning "my son.") and "fasss" (a stylized or phonetically rendered word to describe someone nosy or meddlesome, especially in Caribbean vernacular and Jamaican Patois). These fragments of text hint at familial relationships, street language, and cultural expression, drawing viewers into intimate resonance with themes of race, identity, and belonging.

The materiality of the work underscores Bradford's signature use of found and ephemeral materials to construct layered compositions, transforming discarded or overlooked materials into works of conceptual depth. The use of patches, reminiscent of torn paper or fabric, adds a tactile quality to the piece, reinforcing themes of fragmentation and reconstruction.

In Big Daddy, this technique becomes a metaphor for how racial and class identities are pieced together through personal and societal histories. The handwritten text and repeated imagery suggest the pervasive influence of social roles and cultural labels, while the raw, collage-like textures evoke the struggles and resilience of those who navigate such systems. Through this work, Bradford offers a poignant commentary on the ways personal histories are inscribed by cultural forces.

Lithograph with collage - Private Collection

Shoot the Coin

Shoot the Coin is a monumental work measuring approximately twelve feet high and twenty feet long. At first glance, the canvas appears predominantly white, but closer inspection reveals subtle colors, branching lines reminiscent of blood vessels, and fragments of printed text. Stepping back, the composition transforms into a vast, winter-like landscape, showcasing Bradford's signature technique of layering materials such as paper and string, which he sands and erodes to expose underlying strata.

The intricate and complicated creation process results in a richly textured surface that invites viewers to explore its details while symbolically reflecting the complexities of urban life. Bradford sourced materials for this piece from his surroundings, imbuing it with themes of urban development and its socioeconomic repercussions. The work serves as both a personal exploration and a broader commentary on collective history, illustrating the impact of urbanization on communities and how these forces shape identities and landscapes over time.

This work was included in the exhibition Through Darkest America by Truck and Tank at White Cube gallery. The title of the exhibition was inspired by the former American president Dwight D. Eisenhower's 1919 Transcontinental Motor Convoy, which eventually led to the establishment of the U.S. interstate highway system. The painting reflects on how these highways dissected communities, particularly in Los Angeles, often fragmenting neighborhoods and altering their social fabric. Through this lens, the artwork serves as a commentary on the disruptive effects of infrastructure on urban landscapes and the communities within them; a striking example of Bradford's ability to blend formal aesthetics with social commentary.

Mixed media on canvas - Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Bell Tower

Bell Tower (2014), installed in the Tom Bradley International Terminal of the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), is a monumental and immersive piece of public art. Constructed from plywood, aluminum, and paper, the four-sided structure blends ancient and modern elements, described by Bradford as a fusion of a medieval bell tower and a contemporary Jumbotron. Bradford's choice of materials - recycled paper and weathered wood layered onto a rigid aluminum framework - echoes his interest in the urban environment and its visual language of decay, reconstruction, and resilience. The panels are marked with abstract imagery, evoking a sense of historical palimpsest as though the work is recording stories, advertisements, and movements of the urban landscape over time.

As a child, Bradford often persuaded his mother to take him to LAX, where they would have dinner and watch planes take off and land. During his teenage years, he would skip school to take the bus to the airport, drawn by the allure of the international terminal, particularly the old Pan Am area. Watching planes arrive from destinations like Switzerland or Ghana, Bradford would eagerly rush to the gates, mingling with arriving passengers and pretending he was one of them. "It was the first time I ever heard foreign languages," he recalled. Additionally, he would return luggage carts for a dollar each to earn money for lunch, cementing a relationship with the airport that later inspired his work.

Open at the bottom, Bell Tower reveals its rough interior, inviting passengers to ponder its purpose. Many glance up curiously, unsure whether the piece is unfinished or deliberate. Without any public announcements or press releases about the work, travelers are left to interpret it on their own. Standing beneath the structure, its presence is undeniable - softening the sound of the bustling hall while its raw design juxtaposes the sleek, polished airport environment. "Whether you like it or not, it's contemporary art in an airport," Bradford explained, "and it does exactly what I wanted it to do - makes people think."

Aluminum structure, wood/paper panels - Los Angeles World Airport

Tomorrow is Another Day

Tomorrow is Another Day (2017), presented inside the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennial, is a massive, spiraling sculpture affixed to the ceiling. Its concentric rings resembling a vortex, dominates the interior, forcing viewers to look upward and confront the work's imposing scale. The U.S. Pavilion itself resembles Monticello, the Virginia plantation owned by the third U.S. president Thomas Jefferson. Visitors were required to enter through a side door, replicating the path enslaved individuals would have taken. Bradford filled the inside space with Abstract Expressionist works that drew inspiration from contemporary issues, including the rise of Trump, police violence, and the Black Lives Matter movement. The installation, which Bradford described as his "most urgent exhibition to date," powerfully connected historical narratives to present-day struggles.

The pavilion's title, Tomorrow Is Another Day, echoes Vivien Leigh's closing line from Gone with the Wind, the 1939 historical romance film set during the American Civil War and Reconstruction era. However, Bradford's work extends its focus to confront the legacies of the Civil War. Through his research, Bradford came to see the enduring complexities and unresolved tensions surrounding the Civil War. He noted the ongoing debate in the U.S. over the removal of Confederate statues and pointed to controversial remarks, such as those made by former White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, who claimed the Confederacy acted in "good faith." Bradford sees these debates as an entry point for deeper conversations about race and the country's history. "I think it's a complex and uncomfortable conversation we need to have," he stated. "Then we begin to talk about race in this country in a very fundamental way - who founded it, who built it." Bradford's work challenges viewers to confront these uncomfortable truths and engage with the lingering impact of the past on the present.

Inside US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Life Size

Bradford's Life Size (2019) was created as a conceptual and critical piece for Frieze Los Angeles, presented by Hauser & Wirth. The work explores themes of surveillance and societal control, encapsulated in the form of a body camera - a device increasingly associated with law enforcement and the dynamics of power. By elevating the body camera to an art object, Bradford forces viewers to confront its dual symbolism: as a tool of accountability in the age of police violence and as a potential instrument of oppression. The sleek, almost militaristic design of the object contrasts sharply with its loaded sociopolitical context, inviting conversations about its implications in the digital and social spheres.

The work is hyper-detailed, emphasizing the body camera's utilitarian and invasive nature. By labeling the object with a serial-like number (MBX#a12317p106034) and isolating it against a stark white background, Bradford creates a sense of anonymity and uniformity, akin to mass-produced surveillance equipment. The scale of the piece, larger than life, amplifies its menacing presence, making it impossible to ignore. The interplay between object, scale, and context transforms Life Size into a meditation on the omnipresence of surveillance in contemporary society.

In today's divided society, the widespread documentation of violent encounters - captured through iPhones or police body cameras - has done little to deliver definitive truths. Bradford suggests that such images raise questions about the proper use of force, the assignment of blame, and the notion of righteousness. "There's this idea that a camera will protect its citizens because we will look at the imagery and due justice will follow, but there are so many ways to interpret truth. That hasn't been the case," Bradford explains. "In a way, those body cams are actually representing human bodies, we're taking that imagery, and we're making decisions based on what comes out of that camera. When a verdict comes down to footage, the consequences of something so small are so high."

Cast handmade cotton paper, pigment, gouache, ink, letterpress - Hauser & Wirth

Fire Fire

Fire Fire exemplifies the artist's signature approach of layering materials to evoke a sense of history, tension, and transformation. The work combines vivid hues of gold, blue, orange, and black, creating a chaotic composition that feels both organic and deliberately constructed. Bradford's use of mixed media such as paper, paint, and other urban detritus - imbues the canvas with a tactile richness, giving the impression that the surface is alive with movement and narrative depth.

The title suggests urgency and destruction, as well as a potential for renewal, a duality often present in Bradford's works. The gold and black tones dominate the composition, suggesting both opulence and the aftermath of combustion, while the brighter, fragmented areas of color interrupt the darkness like sparks of resilience or resistance.

Mixed media on canvas - Hauser & Wirth, New York

Biography of Mark Bradford

Childhood

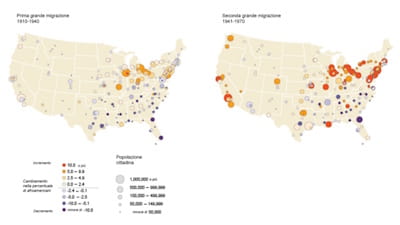

Mark Bradford was born on November 20, 1961, and grew up in a boarding house with his mother and sister in West Adams, an historic Los Angeles neighborhood that had once been a prestigious enclave for wealthy white families. By the mid-20th century, many African Americans moved to the area during the Great Migration. This led to racial tensions and urban changes, like the construction of freeways, which caused many white residents to leave for the suburbs. By the 1950s, middle-class Black families started buying the large, three-story Victorian homes in West Adams at low prices and often turned them into boarding houses. Bradford likened his childhood home to "a raggedy Titanic, grand but fallen on hard times." The residents of the boarding house became an extended family to him; he saw the owners as surrogate grandparents and their adopted daughter, Tennia, as a sister.

Bradford has never known his biological father. Reflecting on this absence, he once remarked, "If I had a father, he more than likely wouldn't like the son I turned out to be." As a gay child who faced bullying at school, Bradford grappled with feelings of rejection from an early age. "At six, I thought, what did I do that was so bad? What sin had I committed? And I realized I did nothing. I was just me. And me wasn't good enough," he recalled, highlighting the profound sense of alienation he experienced in his formative years.

When Bradford was eleven, his mother, Janice Banks, decided to move him and his sister to a small apartment near the beach in Santa Monica. Immersed in this predominantly white community, Bradford quickly adapted, embracing the carefree lifestyle of a "beach kid," spending his days surfing and exploring the streets. However, Bradford's frequent skipping class led to poor grades during high school. In junior year, he transferred to a continuation school designed for under-performing students, where the self-directed curriculum proved to be a better fit. Free from the constraints of traditional schooling, Bradford thrived, focusing on independent reading and excelling in ways he hadn't before.

During his teenage years, Bradford's towering height of nearly six feet eight inches made him stand out in ways that erased his boyish identity. Attempts to conform by playing basketball were short-lived, as the sport's aggression and relentless criticism pushed him to quit. Instead, Bradford turned inward, channeling his energy into intellectual pursuits that sparked his curiosity. He discovered a love for reading, which became a powerful outlet for his imagination.

Early Training and Work

After high school, Bradford began working full-time in his mother's hair salon where he had been involved since the age of eleven. As he recalled, "At that point, I took hair styling classes and got my license." He explained, "I was bridging worlds. I lived in Santa Monica and worked in South Central, but I never thought of myself as a Black kid in a white neighborhood or a West side kid in a Black neighborhood."

In the early 1980s, he embarked on his first trip to Europe, driven by a mixture of motives. Inspired by James Baldwin's Giovanni's Room, he dreamed of visiting Paris, and he was also deeply anxious about the emerging AIDS epidemic, first reported in 1981. "The churches called it God's wrath," said Bradford. "It was so new and terrifying. People said if you stayed out all night and went to nightclubs - which I did a lot because I love to dance - you were definitely going to die. Later, a doctor told me, 'Good news, you don't have AIDS. Bad news, you're going to get it.' Between crack cocaine, drive-by shootings, and AIDS, I thought there was no way I'd survive. I had to leave."

After returning home, Bradford began a pattern of working in the salon for six or seven months to save money before heading back to Europe. "I'd always make sure my mom had the business covered, finding someone to replace me," he said. "I met so many people and had fun - I was young. But there was always a sense of being haunted. Coming back was heavy. Someone would be in the hospital, someone else didn't make it. It was a very dark time."

In 1990, shortly after returning from another stint in Europe, Bradford saw an advertisement for a new program at Santa Monica College offering mentoring and free studio space for two years to promising non-student artists. Although he had only begun to consider becoming an artist, he applied with a small portfolio of paintings and drawings and was accepted. At the time, he continued working at his mother's hair salon, which had relocated to Leimert Park. Bradford had a natural talent for hair styling, relying on intuition and quick problem-solving - a skill his mother praised, saying, "When you can fix a mistake, that's when you know you're good." This mindset carried into his art practice. "I look at a painting and know it's not right, and I'll dig into it," he said. Working late into the night after salon hours, Bradford began producing pieces that caught the attention of Jill Giegerich, a teacher at the college. She encouraged him to pursue professional art training and introduced him to the director of California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), who offered Bradford a full scholarship. At thirty, Bradford enrolled at CalArts.

Reflecting on that period, Bradford said, "It was the first time I slowed down. I'd been moving fast since I was fifteen, but I wasn't fully formed and knew nothing about the art world." During the 1990s, CalArts prioritized art theory over practice, and Bradford immersed himself in writings by theorists like Clement Greenberg, Rosalind Krauss, and Hal Foster. The prevailing belief that painting was obsolete didn't sit well with him, but he set painting aside to explore photography, video, installation, sculpture, and performance. "Painting had grabbed me most at Santa Monica College," he recalled, "but I decided to put it on hold and return to it in grad school if the urge remained." By the time he began graduate studies at CalArts in 1995, that urge was still strong.

In graduate school, Bradford grappled with abstraction. He admired Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Robert Rauschenberg but struggled with the physicality of their materials - oil paint gave him headaches, and Rauschenberg's work felt too heavy for his sensibilities. Instead, Bradford spent hours at a nearby Kinko's printing various ads, texts, and images, collaging them onto large sheets of paper that he would ultimately discard. Faculty members Thomas Lawson and Darcy Huebler encouraged him to preserve his work, which bolstered his confidence, though he rarely found the results satisfying. For his graduate thesis, Bradford staged a conceptual performance, hiring a local high school marching band to parade through his graduation ceremony, an unconventional project that embodied CalArts' emphasis on Conceptual Art.

Mature Period

When Bradford graduated, he doubted he would succeed in the art world. Returning to full-time work at the salon, he paid off his art school loans and relished the community the salon provided. "I was shy, but at the salon, I could talk and make people laugh," he said. He also rented a studio in Inglewood, where he experimented with art after hours.

One day, Bradford noticed a hair end paper - a tissue-thin sheet used for perms - on the salon floor. The way it caught the light inspired him to incorporate it into his artwork. That evening, he took several boxes of end papers to his studio, beginning an experiment that would eventually shape his unique artistic language. Drawn to their translucence and affordability, initially burning the edges with matches, and later using a blowtorch, he created grids with the papers, layering them with thin washes of hair dye before adding another layer. "End papers were fifty cents for a box of two hundred," he explained, contrasting their cost with the prohibitive price of traditional art supplies. He also sourced mismatched paints from Home Depot for a dollar a can, saying that "If Home Depot doesn't have it, Mark Bradford doesn't need it."

The end papers discovery and exploration would evolve into a signature artistic process for Bradford. The process includes preparing a stretched canvas and carefully building its surface with ten to fifteen layers of different types of paper. These include white and colored paper, newsprint, reproductions, photographs, and printed texts, each layer meticulously sealed with clear shellac. To introduce linear elements, he occasionally incorporates materials like string or caulking. Once the surface has reached the desired thickness, Bradford employs power sanders and other tools to strip away portions of the layers, uncovering fragments of earlier strata. This technique reveals vibrant colors, unexpected contrasts, and textured details that add depth to the composition. It is only after this transformative sanding process that the painting's direction begins to take shape, guided by the interplay of the uncovered elements.

In 1997, Bradford first met Allan DiCastro during a Halloween parade. DiCastro, who was raised in a working-class neighborhood in South Chicago as one of five siblings under the care of a single mother, had put himself through Illinois State University before relocating to Los Angeles in 1987. There, he took a banking job and became deeply involved in social causes, eventually serving as president of the Mid-City neighborhood council. Bradford admired his dedication, noting, "I watched him work forty unpaid hours a week for the council." The two frequently discussed collaborating on a community project. "I suggested we start a neighborhood art space," Bradford recalled. "But Allan wanted to go further - combining contemporary art, social justice, and community activism to see what we could create."

In 2001, Bradford completed two significant works with end papers: 43G Spring Honey and 45R Spiced Cognac, named after hair-dye shades. Measuring eight by twelve feet and nine by eight feet respectively, these grid-like paintings featured small rectangles in yellow, cream, and white. Eileen Norton, the first collector to purchase Bradford's work, acquired these pieces. Norton, an educator-turned-collector with deep ties to South Central Los Angeles, discovered Bradford through Thelma Golden, the chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem. Golden, impressed by his work during a 2000 studio visit, featured him in her landmark 2001 exhibition Freestyle. The show spotlighted twenty-eight young African American artists redefining race in contemporary art, a movement Golden termed "Post-Black art." She described Bradford as a "fully mature artist" with a profound grasp of art history and its boundaries, affirming her commitment to collaborating with him throughout her career.

At a financially precarious time, Bradford sold Norton a large and a small painting for $5,000, followed by two more for the same price each. Norton even became one of his salon clients, recalling his frank assessment of her hair. "Mark told me, 'Your hair is not cute.'" When she challenged him to improve it, he replied confidently, "Of course."

Golden's Freestyle exhibition catapulted Bradford into the spotlight, though his rapid success came with challenges. A 2003 solo show at the Whitney Museum's Altria project space received a critical review from Roberta Smith of The New York Times. While she praised The Devil Is Beating His Wife (named after a folk saying about sunshowers), she dismissed other works as "vacuous and discombobulated." Bradford took the critique as a wake-up call, using it to refocus. He soon began Los Moscos ("The Flies"), a monumental ten and one-half by sixteen-foot painting inspired by the vibrant cultural shifts in Inglewood, where Hispanic immigrants transformed the streets with vivid storefronts and lively public life. The painting's title referenced day laborers gathering outside Home Depot near his studio, reflecting the community's resilience and visibility.

Some of his most powerful works from this period explored political themes. While still working part-time at the salon, a client suggested he paint something about the 1921 race massacre. Unfamiliar with the event, Bradford delved into research, uncovering the long-suppressed history of the tragedy, where dozens of Black residents were killed, and one of America's wealthiest Black communities was destroyed. Bradford also recalled his own experiences during the 1992 Rodney King riots in Los Angeles. "There was a curfew, and National Guard troops on the streets, but we put up blackout curtains and kept working," he said. These events inspired pieces like Scorched Earth (2006) and Black Wall Street (2006), where roiling blacks and reds evoke the devastation of Tulsa and Los Angeles, intersected by streaks of white and yellow suggesting resilience amid destruction.

As commented by artist and writer Thomas Micchelli, "By abstracting the stuff of everyday life - rather than treating as an object of irony or ridicule - Bradford is in a very real sense exalting it ... he is folding his own time into a sacred space."

Late Period

In 2009, Bradford was awarded a $500,000 MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant, which allowed him to purchase a historic Art Deco building in Leimert Park. This acquisition enabled him and Allan DiCastro to begin realizing their long-discussed vision for Art and Practice, a private foundation combining contemporary art, social justice, and community activism. Over time, the foundation acquired two additional buildings in the neighborhood, including one that housed Bradford's studio. While renovations are ongoing, Art and Practice has already opened an exhibition gallery and initiated programs such as artist residencies and support for foster youth - a focus inspired by research showing alarmingly high numbers of foster students in local schools. Partnering with the Right Way Foundation, they provide resources like job training and educational support for young adults transitioning out of foster care, operating from what was once Janice Banks' hair salon.

Yet Bradford's art is not confined to didactic or activist approaches. Instead, the artist draws a clear line between his artistic practice and social initiatives. For him, social action serves to complement and support his art rather than define it, with a significant portion of Art and Practice's funding coming directly from his personal income. As he stated, "At the end of the day, I'm an artist. I may make work and decide to do something political, but it will come out of an artist's position. It won't come out of society telling me I have to. If I do, it's because I choose, as an artist, to do it."

Bradford's rise to prominence has been remarkable. His first major retrospective, held in 2010 at the Wexner Center for the Arts, traveled to esteemed museums across the United States, solidifying his reputation in the art world. Today, his work commands impressive sums, with his large-scale paintings selling for up to $1 million in the primary market. Despite his financial achievements, Bradford remains dedicated to innovation and creating meaningful work, continuously pushing the boundaries of his artistic practice.

In 2023, Bradford presented You Don't Have to Tell Me Twice at Hauser & Wirth in New York, his first major solo exhibition in the city since 2015. The exhibition featured monumental canvases that continued Bradford's exploration of the Great Migration of African Americans from the South. Notably, the show included works inspired by European tapestries, depicting flora and fauna native to areas like "Blackdom," an early twentieth-century African American settlement in New Mexico. Through these works, Bradford examined themes of displacement, survival, and resilience, offering a deeply personal perspective on historical and contemporary social issues.

Though Bradford has considered moving to places like Mexico City, Athens, or Venice, he remains firmly anchored in South Central Los Angeles, captivated by its constant transformation. "It's always shifting, eating itself, and becoming something new. I love that energy," he says. He contrasts this dynamism with the rigidity of middle-class suburban life, where manicured lawns and social rules often feel suffocating. "It's like everyone's lawn looks perfect, but I just want to go up there and pee on one of them," he jokes, expressing his disdain for conformity.

Today, Bradford and DiCastro live a block away from his childhood home in South Central. Their residence, which DiCastro has been carefully restoring for a decade, stands as a testament to their shared commitment to the neighborhood that has profoundly shaped Bradford's life and art.

The Legacy of Mark Bradford

In both art and life, Bradford has refused to shrink himself to fit societal expectations or physical spaces. "I don't change for the rooms; I make the rooms adapt to me," he asserts. "I'm going to be Mark all the time, and wherever I decide to be, I belong." This empowerment of one's place in the world coupled with an undying commitment to produce art using innovative materials while remaining engaged with social issues has cemented Bradford a place as a role model for many young artists.

His influence on contemporary art also extends to his nuanced engagement with themes often associated with relational aesthetics. Coined by French art critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud in 1996, the term refers to an artistic practice that prioritizes human interactions and social contexts as the medium of art itself, rather than focusing solely on traditional aesthetics or material objects. In this sense, many of Bradford's works explore the broader dynamics of human relationships and experiences within shared environments, provoking conversations and thoughts among audiences.

As a gay African American man, addressing issues of race, gender, and marginalization, he has inspired artists like Rashid Johnson, whose work explores Black identity and masculine vulnerability. Bradford's engagement with peers such as Theaster Gates, renowned for revitalizing cultural spaces, and Glenn Ligon, whose text-based art interrogates race and sexuality, reflects a shared commitment to addressing social issues through art.

Influences and Connections

-

![Glenn Ligon]() Glenn Ligon

Glenn Ligon - Lauren Halsey

- Theaster Gates

-

![Kara Walker]() Kara Walker

Kara Walker -

![Julie Mehretu]() Julie Mehretu

Julie Mehretu - Rashid Johnson

-

![Social Practice Art]() Social Practice Art

Social Practice Art -

![Identity Art and Identity Politics]() Identity Art and Identity Politics

Identity Art and Identity Politics - Afro-Futurism

- Contemporary Abstractionism

Useful Resources on Mark Bradford

- Mark Bradford (Phaidon Contemporary Artists Series)By Cornelia H. Butler

- Mark BradfordBy Christopher Bedford

- Mark Bradford: Tomorrow Is Another DayBy Peter Hudson

- Mark Bradford: Pickett's Charge HardcoverBy Stéphane Aquin, Evelyn Hankins

- Mark Bradford: End Papers HardcoverBy Michael Auping

- Mark Bradford: Scorched Earth HardcoverBy Connie Butler

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI