Summary of Marianne Brandt

Marianne Brandt is one of the most important artists of the Bauhaus School, and by extension, one of the most influential of all early 20th century designers. Moving up through the ranks of apprentice to head of the Dessau Bauhaus metal workshop, she epitomized the so-called “New Woman” of the Weimar era. Brandt’s “total” utilitarian objects – from tea sets, to lamps, to desk sets - were at once functional and elegantly modern. Her best designs - beautiful to behold in their geometrical simplicity - are today considered icons of early 20th century design. Brandt also became highly regarded for her experimental photography and photomontages. It was through the latter that she began to scrutinize contemporary society and to set about deconstructing myths about women’s place in the age of modernity. Like many of her friends and colleagues, the rise of Nazism stymied Brandt’s career as a professional designer/artist and after World War II she settled into a successful career as an educator and curator.

Accomplishments

- Brandt's willingness to experiment with new materials and design techniques placed her at the center of a movement set on redefining the possibilities for modern industrial design. Totally abandoning her early forays into expressionist painting, Brandt embraced geometric abstraction and the principle that cutting edge design must also meet practical utilitarian needs. Her design pieces are today viewed as the very best incarnations of the famous Bauhaus mantra: “form follows function”.

- Brandt designed many prototypes for commercial production and successfully negotiated contracts with public production providers, including the Kandem lighting company. The Bauhaus/Kandem relationship stopped abruptly in 1933 when the Bauhaus school was shut down by the Nazis. However, Kandem continued producing Brandt’s iconic Kamdem Lamp, an artefact that is singled out today as a benchmark in the development of 20th century interior design.

- Although now widely acclaimed, Brandt’s photography remained largely unknown to the public before being promoted through the Berlin Bauhaus-Archive in 2005. Since then, her photomontages, which saw her unpick gendered and/or political power structures, have offered an insider’s perspective on the so-called “New Woman” of the Weimar era. These pieces have, moreover, brought an added layer of critical complexity to Brandt’s legacy.

- Having left the Bauhaus, Brandt took on the post of head of design at the Ruppelwerk metal goods factory. Denting her early enthusiasm, Brandt found herself pitched against the forces of a hostile management resistant to her ideas of product modernization. Nevertheless, Brandt possessed the mettle to overhaul the company’s ornate forms and decorations by introducing minimalist geometrical designs crafted from modern materials such as metal, enamel, glass, and wood.

The Life of Marianne Brandt

Art historian Elizabeth Otto writes, "In many ways a quintessential New Woman, Brandt is best known for her sleek designs for household objects, which have come to epitomize Bauhaus aesthetics".

Important Art by Marianne Brandt

The Infuser and Strainer

At only three inches high, Brandt’s iconic Infuser and Strainer is devoid of unnecessary ornamentation or embellishment. Her design is characterized rather by smooth, clean lines, and a cylindrical shape that speaks of functional efficiency. In this respect we see clear evidence of Brandt’s ability at balancing artisanship with avant-garde innovation. As the V&A museum describes, “theusual elements of a teapot have been reinvented as abstract geometric forms. The handle, a D-shaped slice of ebony set high for ease of pouring, provides a strong vertical contrast to the object's predominant horizontality. Although the pot’s functionality is carefully resolved, its visual impact lies in the uncompromising sculptural statement it makes. It is defiantly modern”.

Design academics, McDermott and Pandolfo, note that “[Brandt’s] approach moved away from the creation of a purely rhetorical object and towards the consideration of the functionality of the object which became a fundamental principle of industrial design”. Indeed, her design embodied the spirit of the De Stijl and Constructivist movements, both stylistically and in the way it was conceived with the primary goal of entering into everyday life. But, as design academics McDermott and Pandolfo also point out, these high modernist ideals notwithstanding, “the tea infuser was not suitable for mass production at that time and all examples in existence [today] are handmade. Brandt herself wrote about the difficulties of mass producing these types of objects. However, the objects (tea sets, ashtrays etc) designed at this time did attain an iconic status in terms of representing a particular approach and have since been mass produced by Italian homewares company, Alessi”.

Silver and ebony - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Pariser Impressionen (Parisian Impressions)

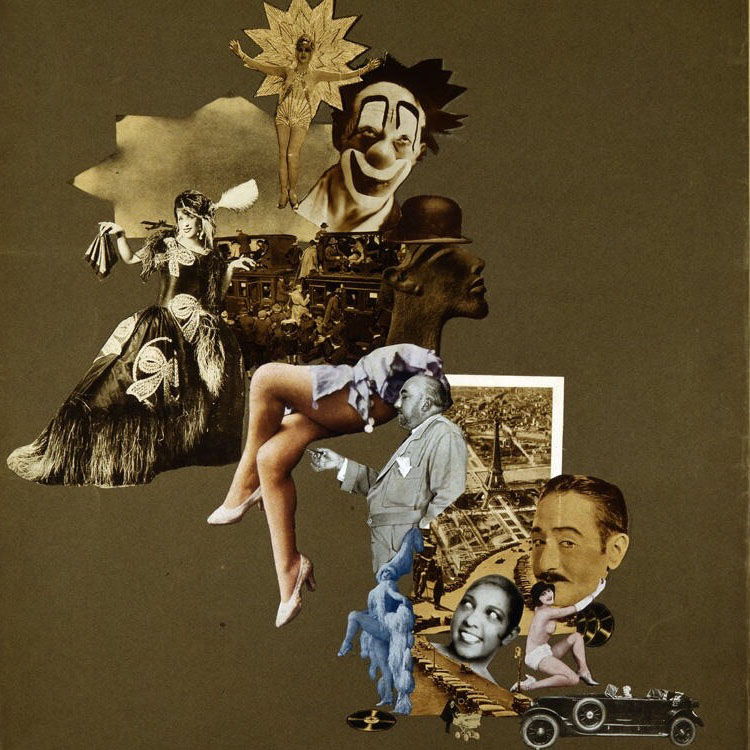

For her photomontages, Brandt was mentored by Moholy-Nagy and his wife, Lucia Maholy. The resultant collages, compiled from the Weimar Republic's vast illustrated press, saw her form critiques of society, its technological evolutions, and, in the case of Parisian Impressions, the role of women in modern society. Parisian Impressions (inspired by Brandt’s own experiences of Paris) offers a vivid portrayal of la garçonne, an image of femininity that emerged in France during the 1920s. La garçonne (a feminization of le garçon, meaning “boy”), symbolized a modern, independent, woman who took on a masculine “tomboy” look.

Brandt’s montage guides the viewer through Paris from the perspective of a flaneuse — a female inversion of Charles Baudelaire’s male secret street observer, the flâneur — whose gaze challenges the perception of women as passive objects of male desire. Brandt’s depiction of modern women in Paris is layered and complex, celebrating their allure while questioning the power structures that shape their lives. Brandt uses the Eiffel Tower as an icon for the city, while feminine spectacle is embodied by the showgirls who fill the composition. Among them is the famous dancer and singer, Josephine Baker (one of the most successful African American performers in French history) gazing toward the center of the montage. She looks askance at a suited male who is fetishizing the disembodied legs of a showgirl.

At the lower-right corner, a woman drives through Paris, joined by the image of headless men in tuxedos in the back seat. This juxtaposition of feminine agency with ghoulish imagery alludes to the dark undercurrents of feminine pleasure and freedom in a modern metropolis like Paris. One figure, draped in blue, suggests femininity as performance, while another in pink represents sexual empowerment. Brandt’s women are joined with an image of the American actor Adolphe Menjou, whose oversized head functions here as a parody of his role in A Woman of Paris (1923), a romantic drama (written and directed by Charlie Chaplin) about a woman torn between true love and a comfortable domestic life.

Photomontage - Collection of the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

Kandem Lamp 702e

Designed by Brandt and Hin Bredendieck, Kandem Lamp 702e represents a turning point in the development of modern lighting design. Offered as a prototype to the Kandem metal factory (in Chemnitz), the lamp’s streamlined simplicity was a radical departure from the company’s over ornate designs of previous eras, and it became the first piece to fully realize the Bauhaus’s commitment to produce affordable, mass produced, modern designs. The lamp is made of lacquered steel, with an ivory matte finish. Its design is minimalist, with a cylindrical base that tapers upward to support a hemispherical lampshade. The curved lines of the shade create a harmonious contrast with the straight edges of the base with the overall effect being one of symmetrical balance. With a metal base that allows for possibility of wall mounting, the Lamp represents a triumph of design and workmanship.

McDermott and Pandolfo write, “Integral to a successful industrial project is the acknowledgment that design is part of a complex system and that developing fruitful relationships is crucial to achieving the goal of product development, manufacture and use. [Kandem lamp No. 702] overcame the threshold of industry production and was manufactured in the many thousands over a period of more than a decade”. The Design Encyclopedia, meanwhile, lists the Kandem Lamp as “a piece of design history that encapsulates the Bauhaus movement’s ideals. Its innovative features and aesthetic appeal underscore the timeless relevance of Bauhaus principles in today’s design landscape. […] pieces like the Kandem Lamp remind us of the [Bauhaus] movement’s enduring legacy in shaping our visual and functional world”.

Lacquered steel - Museum of Modern Art, New York

Untitled (Self Portrait with Camera)

The Bauhaus was fully committed to creating art fit for the modern age and was at the cutting edge in fields including architecture, typography, carpentry, metalwork, weaving, and theater. All these disciplines had dedicated workshops by the time Brandt left Dessau in 1929. But photography had not been taught or promoted within the school. It was Brant’s mentor, László Moholy-Nagy, who had been the most passionate advocate for the advancement of experimental photography. As the Met Museum writes, “He demonstrated unusual camera vantages and various darkroom techniques that were tantalizingly fresh: they constituted, he believed, a ‘new vision’ for a medium that was surely the expressive vehicle of the future”. Brandt carried Moholy-Nagy’s enthusiasm for this (relatively) new medium forward through a series of experimental, untitled self-portraits.

One of her most striking pieces, Self Portrait with Camera, shows Brandt holding up her camera to capture her reflection in a wall mirror in the Bauhaus atelier. She is framed against Gropius’s architectural elements, with a snowy white landscape symbolizing - either ironically or hopefully given that she would leave Dessau Bauhaus the following year - an open and bright future. Brandt’s gaze is direct, and her pose exudes self-confidence. The sharp contrast between light and shadow, combined with the sleekness of her appearance, meanwhile, emphasizes her faith in the age of modernity, and her role in shaping it. Brandt often utilized reflective surfaces, such as metal spheres, to distort her image, and thereby underpinned her primary role as a metalworker. It was an approach that prefigured the performative and conceptual strategies employed by the likes of American artist Cindy Sherman, and British artist, Sarah Lucas, in their own explorations of femininity and self-representation.

Silver gelatin photograph, modern print - Collection of the Bauhaus-Archive, Berlin

Mit allen zehn Fingern (With all 10 fingers)

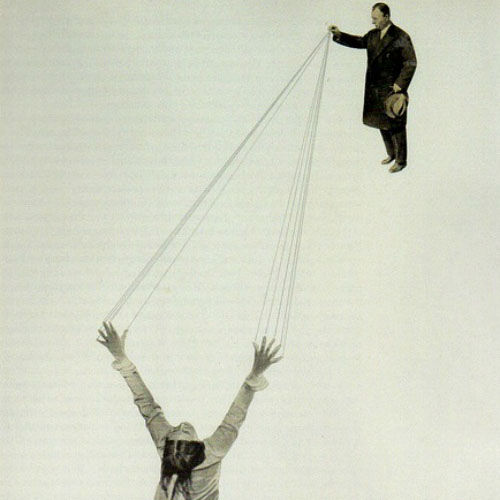

Brandt’s photomontage reads as a commentary on her role as a working woman in the final years of the Weimar Republic, and the stark economic situation in which she (and others like her) found herself. It is one of her bleakest, and most powerful, compositions. Brandt had left the Bauhaus in 1929 moving to the Ruppelwerk GmbH metal factory in Gotha (via a short spell with Gropius at his Berlin studio). It was a very unhappy time for Brandt who, having been brought in to modernize the factory’s ornamental output, faced resistance from an overbearing and conservative management team. With All Ten Fingers portrays a New Woman (Brandt or someone like her) dramatically posed in their fashionable attire. The figure kneels with her head thrown back and arms outstretched, evoking the image of a supplicant before a deity. However, rather than a god, it is a businessman (or manager) who looms above her, tugging at marionette strings that are attached to her ten fingers. The straight pencil-drawn strings connecting them across an empty expanse of paper underscore the power play between the two figures.

The minimalist style of With All Ten Fingers aligns with Brandt’s montages forward of 1929 and reflects the influence of her mentors, Moholy-Nagy and Lucia Maholy. The composition connotes a complex interplay of emotional ties and power dynamics that speak of her feelings of suppression within the Ruppelwerk, and as a woman in the faltering Weimar Republic. Indeed, the central halftone image of the woman, which was cut from the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, was part of an article highlighting the hardships facing aspiring actresses in Weimar Germany. By isolating her subject from her original surroundings, Brandt elevates her as a symbol of the Modern Woman whose livelihood (like her own) was in grave peril. Historian Elizabeth Otto writes, “With All Ten Fingers picks up the montage idiom that Moholy-Nagy was developing at the time to express frustration with the fetters placed on her creativity outside the Bauhaus’s modernist crucible. Not merely reflective of her personal experience, the very acts of working in this avant-garde medium and using the least number of pictorial elements possible were also a rebellion against and an antidote to the kitschy ornamentation of Ruppel’s metal designs”.

Photomontage - Collection of the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

Desk Set

Desk Set represents a period of personal transition for Brandt. Having joined the Ruppelwerk factory, she was given the title: "head of the design department for metal goods in coated steel panel". Brandt set to the task of revising Ruppelwerk's artisan products which were considered over ornate and therefore “unmodern”. She told Gropius that in taking the position her goal was to "bring the confusing and uncharming product range of the Ruppelwerk in line with the Bauhaus philosophy". However, once in post she met with hostile resistance to her project, so much so, in fact, Brandt confided in Moholy-Nagy that she “would not mind to be made redundant”. That she stayed in the factory’s employment (until the end of October 1932 when she was finally released by Ruppelwerk due to its dire financial situation) was out of a basic need to provide financial assistance for her family and friends.

Against the backdrop of this difficult working environment, Otto explains that “Brandt still managed to introduce important changes by entirely removing luxury goods and joke articles from the product line, replacing them with useful products. In terms of the product's design, she also managed to overcome the ornate forms and decorations. Instead, she enlivened the reduced works of coated steel plate with glass elements, wooden balls and chrome parts”. Desk Set was one such work. Comprising a letter opener, inkwell, and paperweight, the individual pieces are crafted from metal, enamel, glass, and wood, with each component formed through geometric shapes and clean lines.

Desk Set was created during a period when the looming threat of the Nazi party was a dark cloud hanging over cultural production in Germany. The Bauhaus, a liberal arts movement dedicated to modernizing the applied arts, felt these pressures most acutely. (Indeed, the School was forced to close after Hitler came to power in 1933, even though its ethos lived on outside of Germany.) Given the political context in which it was produced, Brandt’s work represents then a modest act of artistic defiance. Some historians have, however, queried Brandt’s decision to join the Reichskulturkammer (the Nazi artists’ organization) in 1933 (albeit that this was the only way that artists could legitimately gain access to materials). But, as art critic William Cook argues in his article, “The real story of Bauhaus and the Nazis”, “Like most artists, [the Bauhaus artists] were fairly indifferent to the wider world, absorbed in their own work, generally amoral rather than immoral”.

Metal, enamel, glass and wood - The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Biography of Marianne Brandt

Childhood

Marianne Brandt was born Marianne Liebe in 1893. Very little is known about her early family life, but it is generally thought that she was the daughter of a prominent industrialist residing in Chemnitz, Germany. At the time of her birth, the city was an industrial powerhouse and was often referred to as the “Manchester of Saxony” on account of its thriving textile and mechanical engineering industries. While Chemnitz’s cultural scene was overshadowed by its industries, the city did enjoy a burgeoning arts scene. Wealthy industrialists (possibly even the Liebe family) supported the construction of cultural institutions, such as theaters and museums, and commissioned artworks that merged traditional craftsmanship with modern industrial aesthetics. The city was also witness to the influence of the Jugendstil movement, which emphasized decorative arts and nature-inspired designs that chimed with Germany more generally in its openness to innovation and aesthetic reform.

Early Training and Work

In 1911, an 18-year-old Brandt embarked on her formal arts education at a privately run art school. A year later she transferred to the Weimar Saxon Grand Ducal Art School (130 km west of Chemnitz), one of the few institutions in Germany to accept female students at that time. She spent 1916 and 1917 on a placement in Munich before returning to Weimar Saxon from where she graduated in 1918. Brandt worked as a freelance artist from her own apartment-cum-studio which she shared with her future husband, the Norwegian painter Erik Brandt. They hired a female life model, though Brandt’s portraits were heavily influenced by the decorative Art Nouveau and Expressionist styles as practiced, respectively, by German, Fritz Mackensen, and Austrian, Oskar Kokoschka.

Brandt exhibited her paintings for the first time in 1918 at the Galerie Gerstenberger in Chemnitz. The following year Marianne and Erik were married and set off on extended tours of Norway and Paris before returning to Weimar in 1921. Brandt’s time in Paris opened her eyes to a host of new artistic styles, and once back in Germany, she took courses in sculpture given by Richard Engelmann at the Weimar Academy of Fine Arts. Engelmann was a known for figurative works that created a harmonious blend of the classical elegance and the modernist currents of his time. Having been seduced by the pure functionalist leanings of the Bauhaus, Brandt ceremoniously burned most of her paintings. She said later, "I gave up a career as an independent artist to join the Bauhaus because of the widely held view that two painters [she and Erik] could not really make a living in the long term from those unpaid arts. Furthermore, the Bauhaus held really an almost magical attraction for me”. Brandt joined the Weimar Bauhaus as an apprentice in 1924.

The Weimar constitution mandated that “women should have unrestricted freedom of study” and in his first cost estimate for the new student intake, school director, Walter Gropius, had reckoned on a split of “50 ladies and 100 gentlemen”. It transpired that the school’s mix of sexes was pretty evenly matched. However, most of the female students were channeled into the weaving workshop. Brandt was able to buck this trend with the full backing of the Hungarian, László Moholy-Nagy, who had recently been made Formeister (form master) of the Metal Workshops. He welcomed Brandt onto his programme. She settled in quickly and attended workshops run but other Bauhaus luminaries including Josef Albers, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky.

Moholy-Nagy had replaced the Swiss Expressionist painter and color theorist, Johannes Itten in 1923. Under Itten's leadership, the workshop sought to create works of a highly individualistic nature (Itten’s famously refused to “correct” students’ errors out of fear this would crush their creativity) that drew comparisons with the work produced by the Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshops movement). However, Itten's worldview was at odds with the industrial ambitions of Gropius who wanted to foster a "type of worker, unknown until now, that is suitable for industrial and artisanal activity". Moholy-Nagy, who had taken his lead from De Stijl, and the Russian Suprematists and Constructivists, set about reforming Itten’s syllabus: “We have devoted little to ornamental objects because they cannot be considered part of the elementary needs [of the people]”, he declared.

Brandt later recalled, “At first, I was not accepted with pleasure—there was no place for a woman in a metal workshop, they felt. They admitted this to me later on and meanwhile expressed their displeasure by giving me all sorts of dull, dreary work. How many little hemispheres did I most patiently hammer out of brittle new silver, thinking that was the way it had to be and all beginnings are hard. Later things settled down, and we got along well together”. Working with primary geometric shapes (spheres, cylinders, and cubes) Brandt created unique and finely crafted utilitarian items including a partially nickeled brass ashtray, a silver-plated brass and ebony teapot, bowls, and eggcups. She, and her colleague, Wilhelm Wagenfeld, soon became the standout members of the metal workshop. When the Bauhaus relocated to Dessau, the Brandts moved to Paris where they stayed for nine months. Once back in Germany, Brandt joined the Dessau Bauhaus (in the summer of 1925) when she took primary responsibility for its lighting design. Her ME78B hanging lamp (1926), made of aluminum with a pulley system for height adjustments, became a fixture across the Bauhaus campus.

Soon after joining the Dessau Bauhaus, Brandt made her first excursions into photography, producing a series of abstract photograms (dynamic black-and-white compositions, made by laying objects on photo paper to produce abstract clusters of shapes). However, Brandt’s personal expression found an outlet in the realms of photographic self-portraiture and photomontage. Her self-portraits, including, Selbstportät mit Lilien (Self-Portrait with Lilies) (1923-24), and the photomontage, Pariser Impressionen (Parisian Impressions) (1926–27), document her attempts to come to terms what it meant to be a “New Woman of the Bauhaus”. These works both critiqued and celebrated contemporary femininity blending intimate personal emotions often against a backdrop of urban public spaces. Commenting on her photomontages, New York’s International Center of Photography (ICP) writes, “Brandt first focused her analytical gaze on contemporary society and politics, and, in particular, on the ominous and destructive aspects of modern technology so apparent in the First World War. Drawing on the vast array of visual material made available by the Weimar Republic's burgeoning illustrated press, Brandt’s photomontages relied upon the technologies of modern visual culture to challenge pictorial conventions and imagine new roles for women”.

Mature Period

In April 1927, Brandt accepted a paid position in the metal workshop under the title “Mitarbeiter” (Associate). In 1928, following Moholy-Nagy’s departure, Brandt became the acting director of the workshop, successfully negotiating with private firms for the mass production of Bauhaus products. As design historian Rebecca Viet writes, “This marked a major shift in the school's operations, and the students began designing prototypes for commercial production, a scheme that brought greater public prestige and a stream of income to the Bauhaus. Brandt designed a number of commercially successful objects—including, most famously, the Kandem bedside table lamp (with fellow student Hinrich ‘Hin’ Bredendieck)”.

Brandt left the Dessau Bauhaus in December 1929 when the Swiss architect, Hannes Meyer, became its director. In 1930 she spent five months at Gropius's Berlin practice where she advised on the design for mass-produced and modular furniture. She then moved to the Ruppelwerk GmbH metal goods factory in Gotha where she assumed the role of head of design in the enameled steel household goods department. Here, however, her modernist vision met with resistance from many of the established management. Undeterred, she pushed ahead in her new role and became the only woman to earn a diploma from the workshop. Between 1930 and 1932 Brandt successfully overhauled the product line, gaining valuable experience in designing for the mass market. Most importantly, the position provided her with financial security during the global economic downturn (that followed the 1929 stock market crash). However, the role’s creative limitations — requiring her to pander to middle-class tastes she dismissed as the “kitsch of Grunderzeit [historicizing] of the years following the Franco-Prussian war” — proved exasperating. In a 1932 letter to her friend Marthe Bernson, a despondent Brandt expressed her despair, writing, “Everything is pitch black, and the situation doesn’t seem particularly hopeful for me”. In the autumn of 1932, Brandt was released by Ruppelwerk and she attempted to establish herself as a freelance designer.

By January 1933, Brandt had relocated to Hamburg, but the move proved unsuccessful. The political climate following Hitler’s rise to power drove her to leave Germany altogether. She moved to Oslo, but returned within a month to Chemnitz to care for her ailing father. During the Nazi era, Brandt joined the Reichskulturkammer (the Nazi artists’ organization) to gain access to materials (although she never joined the Nazi party) but her art, melancholic watercolor and tempera paintings, were apolitical and never intended for public exhibition. Brandt received some financial support from Moholy-Nagy and Gropius, but her career had been stalled by the Nazi’s repressive policies and the day-to-day challenges to scrape a living. In 1935 her sense of isolation was compounded when she was divorced by Erik Brandt (following the couple’s long estrangement).

Late Period

In 1936, Brandt suffered another personal setback when her father passed. Navigating the Nazi era largely on her own, she endured significant hardships as her tight Bauhaus network dwindled to sporadic correspondence (many of her colleagues having fled Germany). After World War II, Brandt remained in Chemnitz, where she focused on rebuilding her family home, which had been badly damaged in the Allied bombings. By 1949, she began to reestablish her career as an educator, lecturing at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts from 1949 to 1951 and later, between 1951 and 1954, at the Academy of Applied Art in Berlin. She also visited China where she curated the exhibition Deutsche Angewandte Kunst (German Applied Art) in Beijing and Shanghai.

In the 1970s, a renewed interest in women working in the field of modern art and design brought her to the attention of a whole new audience. In her later years, Brandt dedicated herself fully to teaching, living in East Germany until her death in Kirchberg, Saxony, at the age of eighty-nine. After her death, her body of work was acquired by the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau (Bauhaus Dessau Foundation), ensuring her legacy would continue to inform and inspire future generations.

The Legacy of Marianne Brandt

Marianne Brandt’s name belongs to a select list – Anni Albers (textiles); Benita Koch-Otte (textiles); Otti Berger (weaving); Ilse Fehling (stage and costume design); Margarete Heymann (ceramics); Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp (mural painting) - of pioneering female figures working within the Bauhaus. Excelling in industrial design, Brandt created items such as lamps, ashtrays, and teapots that have become emblematic of the Bauhaus ethos. Her minimalist designs are icons of modernist functionalism and continue to inspire contemporary designers such as in the “objects should never shout” approach as practiced by furniture and product designer Jasper Morrison. McDermott and Pandolfo add that “What is not so well recognised [about Brandt] is her role as an accomplished industrial designer leading a team and collaborating with a manufacturer to create a successful mass produced product. That this was achieved when the profession itself was emerging, points to the magnitude of her accomplishment [and her] deserved place in the pantheon of pioneer industrial designers”.

Brandt is also highly regard for a body of photographic work. Her photomontages in particular picked at the loose threads of modernity in the way they asked viewers to pause and question women’s place within it. As art critic Ben Davis writes, “Brandt seems to have viewed her time at the Bauhaus as a golden age, but one whose promise had deserted her. And her photomontages, with their intimations of the tensions unresolved by the Bauhaus’ promises of progressive industry, are thus infused with a sober kind of wisdom”. It was a view echoed by academic, Melissa A. Johnson, who wrote, “Photomontage, in general, demands careful looking, and Brandt’s are no exception. […] Only with attentive examination do the complex combinations of images, the layers, cut edges, different media sources, become apparent. […] They seem simultaneously to invoke, yet halt, the perpetual movement of 1920s modernity to provide a means of analysis”.

Influences and Connections

-

![Josef Albers]() Josef Albers

Josef Albers -

![Anni Albers]() Anni Albers

Anni Albers -

![Herbert Bayer]() Herbert Bayer

Herbert Bayer ![Hannes Meyer]() Hannes Meyer

Hannes Meyer- Lucia Moholy

-

![Max Bill]() Max Bill

Max Bill ![Charles Eames]() Charles Eames

Charles Eames- Dieter Rams

- Jasper Morrison

- Naoto Fukasawa

-

![Laurie Anderson]() Laurie Anderson

Laurie Anderson ![Charles Atlas]() Charles Atlas

Charles Atlas- Gunta Stölzl

- Alma Siedhoff-Buscher

Useful Resources on Marianne Brandt

- Tempo, Tempo! The Bauhaus Photomontages of Marianne BrandtBy Elizabeth Otto

- Bauhaus Goes West: Modern Art and Design in Britain and AmericaBy Alan Powers

- I Am All Of Glass: 7th International Marianne Brandt AwardBy Linda Pense, Kunstverein Villa Arte Chemnitz Kunstverein Villa Arte Chemnitz

- Marianne Brandt. Fotografien am Bauhaus. (German Edition)By Elisabeth Wynhoff

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI