Summary of Cecily Brown

Cecily Brown might have settled for a comfortable spot in the London art scene where she'd have been quite at home. Just as she was wrapping up her art school studies, the trendy Young British Artists were making their mark. Instead, like countless aspiring artists before her, Brown left London for edgy, make-it-or-break-it New York City. Her meteoric rise to art-world fame included signing on to one of the most prestigious galleries in the world: the Gagosian. Brown is best known for producing huge canvases covered generously with pigment and incorporating sexually explicit themes. Her work is most often compared to that of Abstract Expressionism superstar, Willem de Kooning, which Brown admired intensely. Whereas De Kooning's images of women are often regarded as expressly objectifying of women and even violent, Brown's work has been characterized as a feminist redux of De Kooning's.

Accomplishments

- The genre of the grotesque in painting had been largely dominated by male artists like Francis Bacon and Gilbert & George and their overtly sexualized depictions of women. Cecily Brown was one of the forerunners in the expansion of the genre to encompass the work of female painters. In Brown's depictions of frank sexual subjects, the grotesque prevails despite the sometimes contradictory lavishness of her materials - heavily applied paint and generously varnished canvas. The lavishness itself is expressive, unsettling, and visceral, confirming that the subject matter of a given work is typically intended to disturb the viewer.

- In some regards, Brown is thought to have successfully built her own career on the legacy or, less positively, remnants of the male Abstract Expressionists. She mocks sexuality with equal parts sensuality and repulsion, incorporating what she refers to as "abject ideas about the body, the cheap and nasty." Brown has persisted in her efforts to subvert the machismo of male artists before her, including Ab Ex predecessors de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, and has transformed what might easily be construed as sexism and prurience into a kind of unflinching examination of human nature, including sexuality, violence, and excess.

- Brown is frequently discussed in the context of feminist art. Not unlike preceding feminist artists who actively challenged the canon, which some assert has traditionally presented "masculine" art as exemplary of a kind of performative bravado in the making of large-scale works, Brown has consistently asserted her own artistic authority. While the themes of her work may be construed as feminist to some degree, more importantly, Brown regards her overall approach to art-making as distinctly feminist. She said recently in a related discussion: "I don't drive. I don't cook. I can't do lots of things, and I'm really quite proud of that. Painting is what I can do..."

Important Art by Cecily Brown

Puce Moment

Puce Moment is a large-scale amalgam of multiple, sprawled human bodies depicted in an intense, orgiastic state. Typical of Brown's early work, this one is crowded with partially abstract fragments of genitals, thighs, arms, breasts, and heads with gaping mouths, all in lurid pinks and reds. In works such as this one, sexuality is rendered as grotesque; what might otherwise be construed as sensual because of the rich application of paint and glossy varnish becomes visceral and repugnant.

Brown's early repertoire comments on and challenges the traditional male gaze in the depiction of the nude female form. According to feminist theory, traditionally, representations of the nude female form provided an image of woman to be possessed by the male viewer via the gaze. In pictures such as Puce Moment, male and female bodies alike are grotesque mounds of flesh, parts assembled in a confusing hodgepodge in which male and female are indistinguishable from one another and sex is repugnant. In such a context, the gaze itself becomes repulsive and the possibility of possession is thwarted.

Oil on canvas - Saatchi Gallery

High Society

High Society is a chaotic mixture of erotica and money. Brown frequently titled her earlier works after classic Hollywood films, and this is no exception. The painting is teeming with an assortment of nude, muscle-bound males and high-society men attired in tailcoats and top hats suggestive of opulence and frenetic sensual engagement. Some of the male figures are seen ejaculating into the indiscernible fragments of bodies and penises. The background, a combination of luscious gold and blue, evokes an elaborate Baroque, Rubensian tableaux stretching across massive canvases or a Tiepolo fresco alive with the cavorting nude bodies of ancient gods gracing the ceilings of palatial dining rooms. Brown mocks the vulgarity of such imagery and the entire display in High Society reads as a frenzied mess of sex amidst a gossipy dinner party of the elite, an allusion to the writings of F. Scott Fitzgerald, which the artist cited as a source of inspiration. The colors and the composition of the scene can also be connected to the bright works of Cézanne and to the early abstract pieces by Pollack. As with many an artist, Brown was heavily influenced by the painters who came before her and frequently references them. "A great artist steals," she quipped.

Oil on linen - Saatchi Gallery

Trouble in Paradise

This particular painting recalls the bold color, dramatic brushwork, thick and furious application of paint, and sexualized subject matter of Willem de Kooning's paintings from the early 1950s. Trouble in Paradise marks Brown's shift away from her previous works' literal depictions of explicit sexual content to a more slippery and more elusive approach to representation. Objects seem to be in constant flux and the much looser brushwork succeeds in suggesting rather than the overtly describing body parts.

The left half of the picture offers portions of a woman's anatomy in disjointed pieces lying beneath a blanket of chaotic color. The woman's legs appear to be parted, while a man in the upper right hand corner with gaping mouth peers down at her, exemplifying the leering male gaze. Just to the right of center looms the disembodied nude back of a male turned away from the woman in complete self-absorption, perhaps representing her own erotic fantasy. The severe black background heightens a sense of drama in this piece, adding a sinister tone. Brown explains that her use of somewhat abstract, fragmented figures and objects pushes the viewer to fill in the gaps in order to reveal their own desires when confronted with such elusive narratives.

While, stylistically, still quite similar to her Abstract Expressionist predecessor, Brown makes a definitive thematic break from de Kooning in a kind of symbolic panning out from his almost obsessive, zoomed-in focus on lone female subjects who are rendered hideous by the male gaze. Instead, Brown's feminist pivot implicates the male objectifiers by including them in compositions that leave little question as to the dynamics of the sexual engagement playing out on her enormous canvases.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Hard, Fast and Beautiful

This painting demonstrates the unremitting carnality of Brown's work despite her use of a somewhat muted, minimal palette. A dance of wispy, charcoal gestures mingles with white strokes on the canvas to depict a pair of lovers. The artist represents an erotic coupling as motion, with the lovers tumbling across the surface of the work, smudging and mixing the pigment while engaged in the act. This harkens back to the work of Yves Klein, whose models, covered in bright blue paint, were directed to roll upon and press their bodies to the canvas to create an abstracted impression.

Hard, Fast and Beautiful is a work that demonstrates Brown's transition away from the trademark grotesque images so distinctive of her early oeuvre. They have become abstracted to the point of near unrecognizability, taking on a conceptual quality as she has reconsidered how most effectively to represent the energy of sex. The figures are harder to discern here now and the flesh is no longer represented with the bright, lurid palette of works like Puce Moment. However, the effect is that the awareness of emotion and energy are only heightened.

Saatchi Gallery - Oil on canvas

Black Painting 1

This piece is part of a series of works Brown titled the Black Painting Series, which she named after Francisco Goya's series of the same name. Her series focuses on sex and death, and this particular piece contemplates the connection between the two. In the picture, a night scene, a lone male figure in repose is being tortured by evil spirits. The man is painted in whites and grays, which make him appear ghostly. The smudged body seems to be disappearing as we look on as though the spirits are pulling him into the dark abyss. At the same time, his arched back though and open, exclaiming mouth suggest that he may be in a state of orgasm. The flashes of white overhead are either emanating from the man's body or are closing in on him. The pleasure and torment are obvious and conflicting.

This painting as well as the series itself demonstrates once more Brown's obsession with the work of the Old Masters, whom she references with a frequency suggesting that such paintings are less homages than updates. Specifically, this picture calls to mind Goya's etching, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1799) (not a work from the Black Paintings series, however) as well as Henry Fuseli's The Nightmare (1782) and William Blake's Jerusalem (1820). Like Goya's works from the Black Paintings series, Brown explores dark, disturbing themes using a palette that is unmistakably anxiety inducing in itself.

Oil on linen - The Broad

Combing the Hair (Côte d'Azur)

This work pulses with sexuality, although the darker undertone of many of Brown's similarly themed and populous paintings is missing. Rather than a lurid and chaotic amalgam of whole and partial human bodies rendered in a sometimes heavy-handed amassing of paint and hostile brushwork, Brown depicts a sunny beach in the South of France teeming with nude and partially clad bodies here. The prominent penis on the right side of the canvas leaves little doubt as to the erotic nature of the work and the sweeping brushstrokes reference the title as does the scarcely noticeable crudely articulated blue hair comb in the upper right corner. However, the overall effect of the work in comparison to earlier paintings of similar scale and theme is of frivolity as though something significant has been resolved and sexuality is being celebrated rather than indicted.

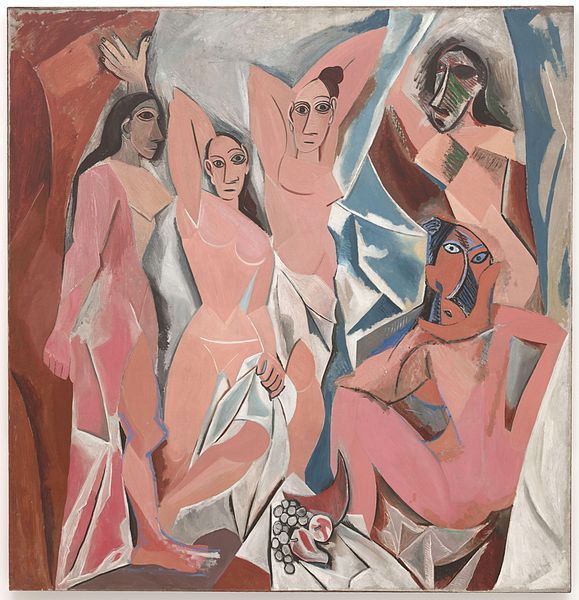

As with so many of her works, Brown references her artistic predecessors, from Matisse's flamboyantly colored, sprawling nudes and Picasso's Demoiselles. The leering cat in the center of the canvas suggests Manet's Olympia, its symbolism: unadulterated carnality.

Gagosian Gallery - Oil on linen

Oh I do like to be beside the seaside

Known for her "bigger-is-better," large-scale works, Brown surprised the art world with a radical U-turn when she began making small-scale paintings around 2004. Even her approach to painting was a departure for, rather than the sometimes physically challenging activity of working on an enormous canvas on the wall or the floor, Brown used a ladder to create an easel at which she stood, literally zooming in while still endeavoring to keep her brushwork loose and gestural. She didn't begin showing these small works, which have been referred to as "jewel-like," until after leaving blue chip gallery, Gagosian in May of 2015.

The small works, most no larger than 17 inches, verge on complete abstraction, although Brown insists that she begins them with a figural concept in order to maintain control and to avoid rendering the works fully abstract and thus, in her view, merely "decorative."

Oh I do like to be beside the seaside takes its title from a popular, early-19th-century British music hall song. While reminiscent of the large-scale, brightly colored orgiastic images of her early career, the recognizable objects such as body parts -- often genitalia -- are absent and instead the canvas is alive with colorful brushwork that emphasize Brown's early association with Abstract Expressionist painters like Mitchell and de Kooning. A decidedly cheerful, picturesque landscape, the painting evokes the Fauves and Cézanne.

39 of the small works, which Brown began referring to as the "Neurotic paintings," appear in a book of her work, The English Garden, which Brown co-produced with American writer friend, Jim Lewis. Her exhibition at Maccarone had the same title. While the small works have been referred to as "a hesitation in the artist's trajectory," for Brown they seem to be explorations of self-control, challenges in containment.

Oil on linen - Maccarone Gallery

Biography of Cecily Brown

Childhood and Education

Cecily Brown, the daughter of British novelist, Shena Mackay, and influential art critic and curator, David Sylvester, grew up in the idyllic countryside of Surrey. As the child of somewhat bohemian parents, she grew up immersed in the arts. Sylvester introduced her to the painter, Francis Bacon, when Brown was still young and the influence of Bacon has remained a constant. Her mother's creativity, work ethic, and drive also encouraged Brown to aim for a career in the arts, although she claims that, by the age of three, she had already decided to become an artist.

In 1985, at sixteen, Brown left her more traditional academic school in order to focus on art at the Epsom School of Art and Design in Surrey. Two years later, she moved to London, where she took drawing and printmaking courses at Morley College, studied under the painter Maggi Hambling, and cleaned houses to financially support herself. Brown had forged a close relationship with Bacon, regarding him as a close friend; the two had grown close while visiting local art exhibitions together. In 1993, Brown graduated from Slade School of Fine Art in London with a BA in Fine Arts and with First Class Honors. While at Slade, she was awarded first prize in the National Competition for British Art Students.

Middle Period

Brown found it difficult to establish herself in the art scene of early 1990s London, at the pulsing heart of which were the Young British Artists with their attention-commanding installations and spectacle works. She believed she might fare better in New York City, where she had fallen in love with the sunlight in a previous stay as an exchange student during her years in college. The contrast between bright, vivacious New York to gloomy London intrigued her, and so in 1995, she made the move across the Atlantic.

Brown began working for an animation studio in New York City and experimented with that medium. She created an erotic mixed-media film titled Four Letter Heaven, which premiered at the 1995 Telluride Film Festival. She was slightly skeptical of painting and first spent her time in the city exploring other creative avenues. As she put down roots in the city, Brown lived the life of the stereotypical starving artist, working as a waitress and living on pizza and bagels. During the evenings, she spent her time making art and eventually began focusing solely on painting in her studio in the Meatpacking district of Manhattan. She painted almost feverishly, typically working on as many as twenty paintings at once.

Brown's large-scale paintings depicted a kind of chaotic and violent sexuality. The works featured a flurry of bodies, which were abstract but still discernible. Her success came fairly quickly, with her first solo show taking place at Deitch Projects in 1997. After a second successful exhibition the following year and the resulting commercial and critical praise, Brown relinquished starving-artist status. At the age of 29, Brown was picked up by the Gagosian Gallery, one of the most esteemed and influential galleries in the world. Although she was represented by a major gallery and her work had begun appearing in prominent museums, Brown, whose confidence in her abilities was easily shaken, was surprised by her own achievement.

During those early years of her mercurial success, Brown shared a studio with the artist, Sean Landers, with whom she also had an intimate relationship. The studio was her safe haven, while the grid of the city was like her refuge. Brown spent as much time as possible in the studio painting almost obsessively and still felt dissatisfied with her productivity. She admitted that, during her early years in New York as a young, up-and-coming artist she drank heavily and partied often, and in some ways welcomed a life of drama and intensity. One of the most dramatic episodes in her life occurred in 2000, when her boyfriend, the artist Russell Haswell, attempted to slit her throat during a particularly heated quarrel and then jumped out the apartment window in an attempt at suicide. The attempt failed and the two parted ways. In retrospect, Brown blamed the myth of the tormented genius artist and the lifestyle that seems to demand that an artist moves between the worlds of the almost manic decadence of New York City and art world life and the rigorous self-discipline of the studio.

Current Work

Brown's style has evolved over time. Her early focus on highly charged sexual themes, with the heavily impastoed canvases of roiling figures was expanded through the years to incorporate more diverse subject matter. Sexual themes are tempered so that there is a subtlety or even vagueness to her work, which the artist says now features a myriad of topics -- "life, death, and the kitchen sink." In May 2015, Brown left the Gagosian gallery after 15 years to the tremendous surprise of the art world. Her more recent work is smaller in scale, with some paintings no more than 17 inches tall. She married architecture critic, Nicolai Ouroussoff and they have a daughter named Ella.

In 2015, her work was at the center of a debate concerning art and appropriation when it was observed that the work of artist, Sherie' Franssen, looked uncannily like that of Brown. The debate featured equal measures of amusement and vitriol on the part of Brown supporters and Brown herself declared that Franssen was little more than a copyist, an assertion that seems a little problematic coming from an artist who made no secret of appropriating themes and styles from past artists.

Brown's career has been the subject of controversy for many reasons. When her work is compared to that of De Kooning, for instance, she's characterized as a kind of "feminist" counterpart to the infamous Ab Ex painter who often portrayed women as hideous monsters. However, critics contend that there is nothing particularly overtly feminist about Brown's work, which New York Times art critic, Roberta Smith, has referred to as "lackluster" and bereft of "necessity."

The Legacy of Cecily Brown

Cecily Brown's emergence as a female artist capable of challenging the gendered status quo not only of the art world but of what many regard as the hyper-masculinity of the Abstract Expressionist movement is perhaps her most lasting contribution. The rhetoric that has traditionally been applied to reinforce concepts of both a feminine style of painting and feminine subject matter, while not completely absent from critiques of Brown's vigorous, unrelenting style and unapologetic themes, stands out as ridiculously anachronistic at the least. The artist's feminism is not and never has been a cudgel but, rather, a brush with which she asserts her skill, energy, and intellect in work that is not especially directly feminist in terms of subject matter but demands its rightful place in the art world and in the larger world where the gender binary is under constant challenge.

Influences and Connections

![Jeffrey Deitch]() Jeffrey Deitch

Jeffrey Deitch![Larry Gagosian]() Larry Gagosian

Larry Gagosian

Useful Resources on Cecily Brown

- Cecily BrownOur PickBy Dore Ashton

- Cecily BrownBy Klaus Kertess

- Cecily Brown: The Sleep Around and the Lost and FoundBy Terry R. Myers

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI