Summary of Elizabeth Catlett

Elizabeth Catlett was a vociferous American artist and activist who confronted the themes of race, gender, and class inequalities through stylish bronze, wooden, and terracotta figurative sculptures, and arresting wood and linoleum prints. In a career spanning 70 years, she found her creative home in neighboring Mexico where she took up permanent residency and joined the radical left-wing printmaking collective, Taller de Gráfica Popular. Curator Melanie Anne Herzog summarized her body of work as "visual declarations of the dignity, strength, vulnerability, and resilience of Black women, Mexican working people, and those suffering under oppression throughout the Americas".

Accomplishments

- Catlett make her mark through sculptures of Black female torchbearers, such as the 18th century poet Phyllis Wheatley, and pioneers associated with the 1960s Civil Rights movement, such as Martin Luther King Jr. But it is her more intimate mother and child series that offer perhaps the most persistent theme in her sculptural work. Overall, her sculptural style is marked by an austerity that, in the words of the Met Museum, "navigates a line between abstraction and realism, cubism and biomorphism".

- Once Catlett took permanent residence in Mexico (in 1947) she joined the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) collective and shared with them their drive to produce politically conscious art. It was through the TGP that she mastered the techniques of wood and linoleum block printing and she became adept at blending Mexican techniques with African-American history. She produced her renowned The Negro Woman graphite and paper series (1946-47), while arguably her single most iconic image, Sharecropper (1946), was produced using the linoleum printing technique.

- Catlett worked in solidarity with the 1960s Black Power movement. One upshot of this relationship was her Singing Head series of sculptures. The Black singing voice had proved a potent tool for articulating the demands of the movement with artists such as Nina Simone and James Brown using their popular singing voices to articulate these concerns. Catlett's Singing Heads, which stylistically carried the influence of Primitivism and Cubism, represented her own faith in the power of song to inspire change.

- During the period of the so-called "Red Scare", Catlett was debarred from America by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAAC) on grounds of her activism and her close associations with communists Diego Rivera and David Siqueiros, and her membership of the TGP (labeled a "Communist front organization" by the American Embassy). Today, however, Catlett, with other Black writers and artists, including Langston Hughes, Lena Horne, and Paul Robeson, are considered heroes of resistance in the telling of 20th century African-American history.

The Life of Elizabeth Catlett

Biographer, Melanie Anne Hertzog describes Catlett as a "visually eloquent [and] pivotal intercultural figure whose powerful art manifests her firm belief that the visual arts can play a role in the construction of a meaningful identity, both transnational and ethnically grounded".

Important Art by Elizabeth Catlett

I Am the Negro Woman

The Met Museum writes that "Many modern artists who sought social justice turned to printmaking as an effective means of informing the public and promoting change. Catlett studied printmaking in Mexico City, where the great public murals by artists such as Diego Rivera impressed on her art's powerful social function. [This is] one in a set of fifteen prints entitled The Negro Woman that Catlett created as a testament to the oppression, resistance, and survival of African American women".

This linocut series, (later re-named the Black Woman), was produced soon after Catlett arrived in Mexico and began attending the Taller de Gráfica Popular (People's Graphic Arts Workshop). It shows the face of a young anonymous Black woman (possibly a self-portrait), turned slightly to the left, and gazing upward with a concentrated expression. Other works from this series include images of notable historical African-American women such as Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Phyllis Wheatley. Catlett once said of the series that she "wanted to show the history and strength of all kinds of Black women. Working women, country women, great women in the history of the United States. [...] I wanted to do something that has to do with all of us. That's what gave me some direction in art".

Recently, curator Heather Nickels has re-examined Catlett's Black Women series as seen through the lens of the "Strong Black Woman trope", which was a term coined in the 1970s, and has its roots in "chattel slavery and the idea that black women, like black men, were not human, and therefore did not have the same emotional issues as white individuals". Nickels suggests that although "a number of the women [in Catlett's artworks] appear to be strong both mentally and physically", it is possible to bring a different meaning to the images and to interpret "what seems to be strength and confidence [rather as] a form of repression and suppression of emotions and emotional trauma that black women experience on a daily basis".

Linocut on paper - Museum of Modern Art, New York

Sharecropper

On childhood visits to her maternal grandparents farm in North Carolina, Catlett learned first-hand of the economic plight faced by sharecroppers, a term that described tenant farmers (many of whom were former slaves) who paid for the land they rented with a portion of their crops. It was a system that trapped many sharecroppers in a life of toil without just reward. When she arrived in Mexico, Catlett took her creative lead from the muralists and other socially motivated artists she mixed with at the artist collective, Taller de Gráfica Popular. This work was to become one of her most famous, and was first exhibited in 1952 in Atlanta, under the title Negro Woman. It was also printed in the journal Artes de Mèxico in 1957, under the title Cosechadora de Algodón (Cotton Harvester). Indeed, in printmaking, Catlett had found the most expedient and democratic medium (in that it is relatively inexpensive, and more easily disseminated to a wide audience) with which to offer a voice "for people who do not have one".

While in Mexico, Catlett learned of the concept of mestizaje, a term that describes the blending of Indigenous and European bloodlines, and Mexican cultures. She saw a further parallel between the experiences of agrarian workers in Mexico and the sharecroppers in the United States. In Sharecropper, Catlett presents her figure from a low angle, imbuing her (or him?) with a sense of everyday heroism. Curator Anne Umland writes that "Sharecropper is hardly intended to arouse pity or rage: its composition and cropping make the viewer look up at this figure as someone to be respected and even venerated. The safety pin that holds her jacket closed is a succinct sign of poverty, while her broad-brimmed straw hat would have sheltered her from the sun when working the fields. The economy of the print's narrative is countered by the variety of its patterns and marks and its dramatic lighting. These, along with the simplified planes of the figure's body, face, and hat, demonstrate Catlett's modernity".

Linocut on paper - Museum of Modern Art, New York

Mother and Child

During her career, Catlett sculpted many versions of Mother and Child. This 1956 version uses the pre-Hispanic hollow terracotta form which she had learned from Francisco Zúñiga Chavarría (considered by many to be the most important sculptor in the modern Mexican style). Curator Anne Umland notes that in this, and similar Mother and Child sculptures by Catlett, "the faces are ethnically specific, including tenderly detailed aspects of Black physiognomies such as tightly curled hair, broad noses, and full lips. The body of the mother, by contrast, is generalized: despite its small size, it has the gravity and weight of one of Michelangelo's sibyls, or, closer to Catlett, of the monumental, muscular types seen in the paintings of Catlett's contemporaries the Mexican muralists".

Umland continues that "The asymmetry of the mother's pose contributes to the sculpture's dynamism, while her downturned gaze and particular quality of physicality - its private, protective, introspective tenderness - likely owe to Catlett's own experience as a mother: the impression is less of a model observed than of memories of what it feels like to cradle the weight of a child". By way of comparison, some of her earlier Mother and Child sculptures (those produced between 1939-41 and before she became a mother herself), although accomplished and elegant, lack the emotional weight of this later version.

Artist and art professor Wendell Brown has put forward the interesting hypothesis that Catlett's sustained interest in the Mother and Child theme fomented during her time at the University of Iowa in the late 1930s where she roomed with African-American writer and poet Margaret Walker. Like Catlett, Walker's grandparents had been slaves and, like Catlett, her grandmother would recount her experiences of female servitude. Brown suggests that Walker's 1966 novel, Jubilee, was based on these stories, and focuses on the theme of African-American motherhood. He envisions a scenario in which Catlett and Walker were "swapping the stories" their grandmothers had told them, and developed parallel accounts (in art and literature respectively) of the themes and messages that arose from those conversations.

Terracotta - Museum of Modern Art, New York

Seated Woman

Curator Melissa Wolfe has called Seated Woman "a marvelous example of the strong female form, mix of naturalism and abstraction, lustrous finish and incorporation of wood grain into the subject for which Catlett is most celebrated". Although she learned much about sculpture from Mexican artist Francisco Zúñiga during the late 1940s and 1950s, arts administrator Delyn Stephenson observes that "In contrast to Zúñiga's women, who were often languid, and almost appear to be in their own world, Catlett's women are heavy, centered, and take up space, invoking Catlett's intention to portray social realism in her work and represent gender and race in very white and male-dominated artistic spaces. [...] She believed that affirmative depictions, such as in this sculpture, were a means toward social change". Catlett produced several other versions of Seated Woman (in wood and bronze from the 1960s through the 2000s) and although their styles, expressions, and positions differ, all convey a similar sense of strength, solemnity, and feminine presence.

Stephenson continues that in Seated Woman, "the sculpture surface has been finished to a smoothness that emphasizes the grain of the wood. You can see the outlines of the woman's clothing. Catlett reveals the shape of the body, with elegantly rounded forms, broad hips and shoulders, and firmly placed legs". It is in this way, indeed, that the form and positioning of the woman's body references pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican sculpture. At the same time, notes Stephenson, "the woman's face, like most of Catlett's women, is considerably more stylized than the figure, drawing [inspiration] from African art". The artist herself stated that she was moved by "black beauty, not the female nudes of the European artists, but the women of the African wood carvers and the pre-Hispanic stone carvers".

Mahogany - Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri

Students Aspire

In 1974, Catlett's alma mater, Howard University, invited twenty artists to submit proposals for a sculpture to grace the entrance to its new chemical engineering building (in the School of Engineering). The seven finalists submitted models and maquettes to a university arts committee. After a long drawn out selection process, Catlett (who had been honored by the university with a solo exhibition two years earlier) was finally chosen to realize her project. Students Aspire is a 1½ ton bronze statue featuring a male and female figure with outstretched arms holding aloft a medallion adorned with an equal sign. The four medallions that complement the figures are symbols connected to the science of engineering, while the base of the sculpture sees the couple standing on a platform containing the roots of a tree adorned with human faces representing the idea of the growth of knowledge for all. Black Art: An International Quarterly said of the work (in 1977) "The two students are holding each other up to express unity rather than the competition that exists in education. The equal sign signifies scientific as well as social equality - that everyone should be equal; men to women, students to faculty, blacks to everyone else".

The Smithsonian Archive of American Art writes, "On May 12, 1978, at the formal unveiling of Students Aspire, the Acting Dean for Howard University's School of Engineering, Dr. M. Lucius Walker Jr., called upon the words of civil engineer Samuel C. Florman, in his work The Essential Pleasures of Engineering, to comment on the nature of arts and sciences collaboration. 'Humanists may be pleased to see us (engineers) relying upon the creative artist,' Florman wrote. 'Of course we rely upon the artist! . . . He is our cousin, our fellow creator.' What Florman so eloquently articulates here, and what Dr. Walker sought to reiterate in his opening remarks, is the truth of the proximity artists and scientists already share: that the artist has a knowing bond with the engineer, for she, too, is an inventor. For artists like Elizabeth Catlett, who are known for their sculpture work with metals, woods, and marble, the shared body of science and art is all the more undeniable. After all, for the sculptor - whose hands must use force and fire to transform material - engineering is an art form for constructing both objects and ideas".

Bronze - Howard University School of Engineering, Washington D.C.

Singing Head

This 1980 version of Singing Head is one of a number carrying the same title (including a bronze (1968), another in tropical wood (1975), and another carved from red onyx (1979)). The root of these works lies in the 1960s when "vocal empowerment" became a key component of the Black Power movement. Indeed, the Black singing voice was a potent tool for articulating demands for social and racial equality, with artists such as Nina Simone, James Brown, Stevie Wonder and Sly and the Family Stone using their singing voices to broadcast these concerns. Catlett's Singing Heads represent the artist's shared faith in music's ability to inspire change.

This later version is significantly more abstracted than its predecessors. While living in Harlem in the mid-1940s, Catlett studied with Russian modernist sculptor Ossip Zadkine who pushed her to introduce elements of abstraction in her figurative work. The African-American artist Unity Lewis (grandson of esteemed artist and historian Samella Lewis) notes, "the left side is never identical to the right side of a person's face when you look at [Catlett's] work, because that's not how it is in nature [in this incarnation of Singing Head] one side is pretty figurative and geometric and the other side goes super abstract". The Smithsonian Art Museum adds that "To Elizabeth Catlett, the face is a key to both racial identity and the inner essence of humanity. This is particularly true of Singing Head, part African, part pre-Columbian in derivation. The enigmatic, undulating form exudes a somber vitality suggestive not simply of the power of song but of life itself".

Black Mexican Marble - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.

Biography of Elizabeth Catlett

Childhood

Alice Elizabeth Catlett was the youngest of three children (two girls and a boy) born to middle-class African-Americans John and Mary (born Carson) Catlett. She grew up in Washington DC in a house built by her grandfather. Her father was a teacher in the local public school system, having previously taught math at Tuskegee University, Alabama. Sadly, he died while his wife was pregnant with Elizabeth leaving his widow to provide for her children emotionally and financially. Her mother worked several jobs, including one as a high school truancy officer. Catlett became absorbed with art from a very young age and remembered being especially fixated on a bird that her late father had carved from wood.

The Catlett siblings spent many hours in the care of their paternal grandparents. They had been freed slaves and they passed down first-hand accounts of slavery, and stories of their African heritage, to their grandchildren. Catlett also enjoyed summer vacations in Durham, North Carolina, at the home of her maternal grandparents. Here she became captivated by the work of local sharecroppers (the memory never left her and would later provide her with the subject for one of her most iconic artworks). Back in Washington DC, Catlett attended Lucretia Mott Elementary School before enrolling at Dunbar High School, an academically elite public school, and the first high school to serve African-Americans in the United States (she made her first-ever sculpture, an elephant carved out of soap, at Dunbar). Catlett's early concern for issues around racial identity was no doubt reinforced by her art teacher who was a direct descendent of abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Catlett graduated from Dunbar in 1933.

Education and Early Training

Following her graduation from Dunbar, Catlett won a scholarship to attend the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, but in the era of segregation, her offer was rescinded when the school learned of her color. She was, however, welcomed into the historically Black Howard University in Washington DC, where she initially majored in design and drawing before transferring to painting. Her mother had saved enough money to cover the fees for her first semester, and Catlett won scholarships to cover future education fees.

At Howard, Catlett was taught by artists James Herring, James Porter, and James Lesesne Wells, and philosopher Alain Locke. One of her most influential teachers was the renowned African-American educator and artist, Loïs Mailou Jones. Catlett graduated with honors in 1935 but believing a successful career as an artist was beyond the reach of a Black woman, she moved to her mother's hometown of Durham, where she took up the post of art teacher at Hillside Highschool. However, Catlett was unhappy with the fact that Black teachers were paid less than White teachers, and campaigned (albeit unsuccessfully), with her colleague Thurgood Marshall, for equal pay.

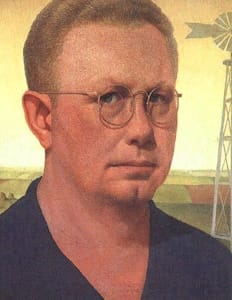

Around this time, Catlett developed an interest in the paintings of Grant Wood and enrolled in a Masters' program at the University of Iowa (where Wood taught). While there, she studied drawing and painting with Wood, and sculpture with Harry Edward Stinson. She lived off-campus, and her roommate was African-American writer and poet Margaret Walker. In 1940, Catlett graduated with two other students in the first cohort to earn a Master's Degree in Fine Arts from the university (with Catlett also being the first woman to do so). Curator Melanie Anne Herzog writes, "Her description of her thesis carving, Negro Mother and Child, in the written portion of her Master of Fine Arts thesis reveals her attention to the relationship of subject, form, and materials, as well as why her chosen subject mattered to her: 'To create a composition of two figures, one smaller than the other, so interlaced as to be expressive of maternity, and so compact as to be suitable to stone, seemed quite a desirable problem. The implications of motherhood, especially Negro motherhood, are quite important to me, as I am a Negro as well as a woman'". Negro Mother and Child won first place in sculpture at the 1940 Chicago American Negro Exposition.

Catlett moved on to New Orleans to teach at Dillard University, where one of her students was African-American artist, curator and historian, Samella Lewis. Lewis later recalled the time Catlett took a class to the Isaac Delgado Museum of Art (now the New Orleans Museum of Modern Art (NOMA)) to see a Pablo Picasso exhibition. As the NOMA now tells it, "much of the city was racially segregated, including City Park - and, by extension [the Isaac Delgado] Museum of Art. As the chair of the art department at Dillard University from 1940 to 1942, Catlett was determined that her students should have the same access to art as their white peers [and] defied segregation orders to arrange for her students to visit [the exhibition]. For most of them, it was their first time in an art museum". Lewis duly acted on Catlett's instruction to her students to collect each other's work and to "see themselves and have ownership of a history of themselves".

Catlett spent the next summer in Chicago, studying ceramics at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and lithography at the South Side Community Art Center. It was in Chicago that she met fellow Black artist Charles W. White, whom she married in December 1941. Herzog writes "[the summer of 1941 in Chicago] was the height of the Chicago Renaissance, a vibrant period of community based, socially engaged cultural expression by Chicago's Black visual artists, writers, musicians, and dancers. Their overtly progressive and radical politics and their assertion of the power of 'art as a weapon' mark the fundamental difference between the Chicago Renaissance and the earlier 'Harlem Renaissance' [and that many of the Chicago artists, including White] were more critical than their Harlem Renaissance predecessors in their portrayals of Black community life as circumscribed by race and class oppression".

In 1942 the couple moved to New York where they were befriended by artists and intellectuals, including W. E. B. Dubois, Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglas, and Paul Robeson, who had been connected with the earlier Harlem Renaissance. Catlett studied lithography at the Art Students League of New York, and took classes with Russian modernist sculptor Ossip Zadkine, who pushed her to explore abstraction in her work. While at the Students League Catlett also studied with Raúl Anguiano, one of the founders of the Mexican Taller Gráfica Popular (TGP) printmaking collective. Her friendship with Anguiano fuelled Catlett's desire to visit Mexico.

Catlett taught adult education classes (in sculpture and sewing) at the George Washington Carver School in Harlem (where her coworkers included Black artists Gwendolyn Bennett, Ernest Crichlow, and Norman Lewis). Herzog states that "she learned from her students about how their economic circumstances shaped their lives [and this] solidified her awareness of the privileges afforded her by her education and the ways that her middleclass upbringing had circumscribed her understanding of the hardships endured by working-class people and those living in poverty. Deeply moved by what she termed the 'cultural hunger' of the women with whom she worked at the Carver School, Catlett sought a Julius Rosenwald Fund Fellowship to produce, as she wrote in her 1945 fellowship application, a "series of lithographs, paintings, and sculptures on the role of the Negro woman in the fight for democratic rights in the history of America'". Catlett was awarded the Fellowship to study in Mexico.

Catlett had already developed her interest in muralism in the mid-1930s when she had been employed with the Works Progress Administration (although she was fired two months for lack of initiative and experience). White accompanied her to Mexico, though they revisited the United States to divorce within a year. Catlett returned to Mexico as a permanent resident. She befriended muralists Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, painter Frida Kahlo, and printmaker and muralist Francisco Mora. Through her connection to Mora, Catlett joined the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) printmaking workshop. Catlett and Mora were married in late 1947, later raising three sons, Francisco, Juan, and David (all of whom also grew up to work in the arts).

Art historian Leah Dickerman explains that, "The [TGP] printmaking collective made presses, tools, acids, and inks accessible to all to facilitate the emergence of a new working class artist who would create inexpensive, reproducible art for revolutionary change - championing the poor, denouncing Western imperialism and economic exploitation, and calling out hypocrisy. It was as much a discussion group as a workshop". Catlett once recalled that "People would come to the workshop if they had problems: if the students were on strike; or trade unions had labor disputes, or if peasants had problems with their land, they would come into the workshop and ask for something to express their concerns. [...] I learned how you use your art for the service of people, struggling people, to whom only realism is meaningful". Works with titles such as, In the Fields; In Sojourner I Fought for the Rights of Women as well as Negroes; I am the Negro Woman; In Harriet Tubman I Helped Hundreds to Freedom; and I Have Always Worked Hard in America (all between 1946-47) were indicative of Catlett's committed socialist leanings.

From 1948, Catlett attended Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado (known colloquially as "La Esmeralda"), where she studied wood sculpture with José L. Ruíz, and terracotta sculpture with Francisco Zúñiga. Although she had shifted her focus from printmaking to sculpture, Catlett continued to be involved with the TGP for a further two decades. Catlett also became the head of the sculpture department at Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in 1959. Despite protests against her appointment based on her gender and foreigner status, Catlett remained in post until her retirement in 1975. Speaking about the differences between her printmaking and sculpture, Catlett stated, "I'm thinking differently in the two mediums. In the printmaking, I'm thinking about something social or political, and in the sculpture, I'm thinking about form. But I'm also thinking about women, Black women".

Mature Period

In the 1950s, Catlett was investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAAC) because of her close associations with communists White, Rivera, Kahlo, and her continued membership of the TGP, which the US government had declared a "Communist front organization". As Hertzog explains, "Like other US leftist expatriates in Mexico, she had been subjected intermittently to harassment by the United States Embassy throughout the 1950s. Her decision to seek Mexican citizenship came after she was forcibly taken from her home by the Mexican authorities and imprisoned as a 'foreign agitator' during a strike by railroad workers in 1959. Her arrest was part of a move by the Mexican government to suppress trade unionists and the left, an effort that included the arrest and deportation of US citizens living in Mexico who were designated 'Communist' by the US Embassy. Soon after her release from prison, Catlett applied for Mexican citizenship to avoid further mistreatment and possible deportation. When her Mexican citizenship was granted [in 1962], she was immediately labeled an 'undesirable alien' by the US authorities and barred from her country of origin".

Catlett's first Mexican solo exhibition was held at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plàsticas, San Carlos, in 1962, the same year as her large-scale work, Figura (1962), won the Tlatilco prize in Mexico's first national sculpture biennial. These pieces saw her remain essentially true to her preference for figurativism despite the wider post-war shift towards abstraction. In 1963, Catlett was among nearly 100 Mexican women who traveled to post-Revolution Cuba for the Congress of Women in the Americas. Newly galvanized, she returned to Mexico where she helped form the Unión Nacional de Mujeres Mexicanas (National Union of Mexican Women) which was committed to fighting for the civil rights of the campesinas (Mexican peasant women). In 1964, Catlett produced Mujer (Woman), a life-size wood sculpture dedicated to the dignity of the campesinas.

Late Period and Death

Hertzog explains that "Despite her expatriate status, Catlett had not been forgotten in the United States. As a younger generation of African-American artists claimed her as a foremother, her work found renewed visibility. A 1970 article in Ebony magazine, 'My Art Speaks for Both My Peoples', highlighted her status as an accomplished artist and educator in Mexico and emphasized her Black Nationalism. One photo caption reads, 'Armed with power tools and chisels, Miss Catlett begins the liberation of another of her figurative Black sisters imprisoned in a log'". In 1971, with the support of colleagues and friends who wrote to the US State Department on her behalf, Catlett obtained a special visa to attend the opening of her solo show at the Studio Museum in Harlem. In 1975, having retired from teaching at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, Catlett moved to the city of Cuernavaca, Morelos. By 1983, she was allowed to freely enter and leave the United States and she and Mora bought an apartment in Battery Park City, New York, where they lived a portion of each year.

Despite her increased visibility on the contemporary United States art scene, Catlett's art had not gained the same level of critical attention as it had done in Mexico. That situation changed in 1993 when New York's June Kelly Gallery opened an exhibition of her sculptures to great acclaim. It led to future solo exhibitions across the United States with works being acquired for the permanent collections of the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian, and New York's Metropolitan Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art.

In 2002 Catlett regained full American citizenship. The following year she received the International Sculpture Center's Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2007, a new residence at the University of Iowa was named in her honor. In 2008, Jared Leigh Cohon, president of Carnegie Mellon University, having learned that Catlett had been denied admission decades earlier (on the basis of her race), presented her with an honorary Doctorate. Catlett passed away peacefully in her sleep at her home in Cuernavaca on April 2, 2012, at the age of ninety-six. She was survived by three sons, ten grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.

The Legacy of Elizabeth Catlett

Many academics and historians have cited Catlett as torchbearer for female African-American artists of the last century, and advocate for continued (and greater) recognition of her accomplishments. She was, as curator Lucia Olubunmi Momoh has noted, "one of the earliest recognized Black women artists whose work focused on uplifting other Black women and girls". As Catlett herself stated, "No other field is closed to those who are not white and male as is the visual arts. After I decided to be an artist, the first thing I had to believe was that I, a black woman, could penetrate the art scene, and that, further, I could do so without sacrificing one iota of my blackness or my femaleness or my humanity".

And yet her art resonated within a wider context of socially engaged art through her long and close alliances with Mexican art and culture. The National Museum of African American History and Culture states that, "'Ni de aquí, ni de allá' is a common saying amongst Latinxs with ties to Spanish speaking Latin American and Caribbean nations. The phrase translates to 'Neither from here, neither from there.' It articulates a sense of displacement that occurs when belonging is shared between two places and not being fully accepted in either because of this hybridity. Contrastingly, Elizabeth Catlett found a way to be 'de aquí y de allá,' 'from here and from there.' She harmonized her African-American identity with an adopted Mexican identity through her life, art, and activism that resulted in an embrace from her two homes".

Influences and Connections

-

![Grant Wood]() Grant Wood

Grant Wood -

![Diego Rivera]() Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera -

![David Alfaro Siqueiros]() David Alfaro Siqueiros

David Alfaro Siqueiros - Lois Mailou Jones

- Francisco Zúñiga

-

![Frida Kahlo]() Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo -

![Jacob Lawrence]() Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence -

![Aaron Douglas]() Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas ![Charles White]() Charles White

Charles White- Gwendolyn Bennett

-

![Mexican Muralism]() Mexican Muralism

Mexican Muralism -

![Social Realism]() Social Realism

Social Realism -

![Identity Art and Identity Politics]() Identity Art and Identity Politics

Identity Art and Identity Politics -

![Harlem Renaissance]() Harlem Renaissance

Harlem Renaissance - Chicago Black Renaissance

- John T. Biggers

- Unity Lewis

-

![Frida Kahlo]() Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo -

![Jacob Lawrence]() Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence -

![Aaron Douglas]() Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas ![Charles White]() Charles White

Charles White- Gwendolyn Bennett

Useful Resources on Elizabeth Catlett

- Persevere and Resist: The Strong Black Women of Elizabeth CatlettBy Heather Nickels

- Elizabeth Catlett: Works on PaperBy Jeanne Zeidler

- Elizabeth Catlett: In the Image of the PeopleBy Melanie Anne Herzog

- Elizabeth Catlett, Sculpture: A fifty-year retrospectiveOur PickBy Lucinda H. Gedeon

- Elizabeth Catlett: Art for Social JusticeBy Klare Scarborough

- The Art of Elizabeth CatlettBy Samella Lewis

- Struggle and Serenity: The Visionary Art of Elizabeth CatlettBy Mora J. Beauchamp-Byrd and Gayle Louison

- Black Artists in America: From the Great Depression to Civil RightsBy Earnestine Lovelle Jenkins

- Women Artists of the Harlem RenaissanceBy Amy Helene Kirschke

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI