Summary of Louis Daguerre

The influence of Daguerre's intervention on the shaping of the industrialized world is hard to overestimate. Having carved out a successful career as a theatrical scenery painter, the Frenchman turned to science and optics in search of a way of improving the production of his profitable entertainments. His move into the nascent field of photography led him ultimately to the development of his daguerreotype camera; the first form of mechanical reproduction to produce a finely detailed and permanent photographic record. The daguerreotype, which quickly spread throughout the world, proved to be the catalyst that has altered the way we have come to view and represent our world, including the radically altered perception of art, and what its function was; or what it should, or could, become.

Accomplishments

- Opinions differ as to when one can date the start of modernism, but there can be no doubt that Daguerre's "technological miracle" sent a shockwave through the sciences and the visual arts. Indeed, the daguerreotype "machine", which recorded the world with much more fidelity than the human eye and hand ever could marked a decisive turning point in the history of art.

- On the one hand, the daguerreotype had delivered a profound blow to the world of art by rendering realist painting all-but passé. But the daguerreotype had also liberated the artists in the sense that he or she no longer carried any responsibility for representing his or her world literally. For better or worse, Daguerre had effectively announced a brand new era in art history; an era marked by unprecedented experimentation and innovation.

- As camera technology improved, equipment became more mobile, and art photography more spontaneous and playful. The careful staging that was the daguerreotype's legacy lived on however in the "higher", or "spiritual", developments in the photographic arts. The fixed large format image came to define Straight Photography which created high contrast, sometimes semi-abstract, images that were reliant on size and context (usually a gallery wall) to realize their full aesthetic potential.

- The privilege hitherto of the bourgeois classes, the daguerreotype allowed for the democratization of expensive and time consuming painted portraiture. For the first time, the working classes could afford to create histories and mementoes of their own lives (and sometimes deaths) through photographic images that would adorn their walls and mantlepieces.

- Daguerre was quick to signal the huge potential for the medium of photography. With a view towards the sciences, he created images of dead insects; while in respect of the arts, he created images that captured light and shadows in expressive ways. He also experimented with microscopic and telescopic versions of the daguerreotype enabling him to photograph subjects ranging in scale from spiders to the moon.

The Life of Louis Daguerre

Daguerre believed that the "most useful and extraordinary [...] instruments of science" were those, like his daguerreotype, that were valued equally for the "influence which they exert upon the arts".

Important Art by Louis Daguerre

The Ruins of the Holyrood Chapel

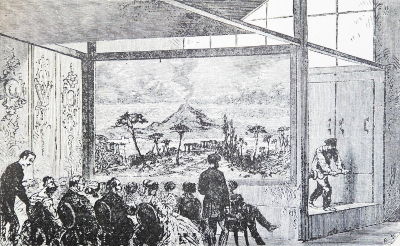

Daguerre's name is inextricably linked to the invention of practical photography but he had already made a name for himself with his extravagant diorama entertainments which proved hugely popular amongst Parisians (and Londoners) during the 1820s. His purpose-built, revolving, theater featured finely detailed architectural ruins and panoramic tableaus painted (by Daguerre and his colleague Charles Marie Boulton) onto 70 by 45 ft transparent linen sheets which would then be "brought to life" through lighting and sound effects (and sometimes even performers and stage props). The Ruins of the Holyrood Chapel proved to be one of his most popular diorama presentations.

In order to perfect his dioramas, Daguerre would prepare oil sketches through which he tested various color effects. Occasionally, he displayed these as easel paintings as was the case here. The Ruins of the Holyrood Chapel was in fact exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1824 with the historian and founder President of the Third Republic, Adolphe Thiers, declaring that "the appreciators of the beautiful, by approaching the table of Mr. Daguerre, had the [...] advantage of enjoying its execution, so firm, so broad and so dexterous in details", and the director of the Louvre, Louis Nicolas Philippe Auguste de Forbin, hailing Daguerre as "one of the most remarkable [painters] of the time".

It is not known whether Daguerre visited the historical Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh, though several early 19th century artists and writers had been drawn to the rich history of Scotland due largely to the popularity of Sir Walter Scott's novels. In fact, Daguerre painted two other Scottish views - Esquisse de l'Intérieur de l'Abbaye de Roslyn (1824) and Personnages Visitant une Ruine Médiévale (1826). What becomes evident through studies of interior ruins is that Daguerre was able to finesse the various ways lighting worked through his unique diorama tableaus. Indeed, the oil painting captures all the illusionism of gothic drama within the decorative detail of the architectural ruin.

Oil on canvas - Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, UK

L'Atelier de l'artiste (The Artist's Studio)

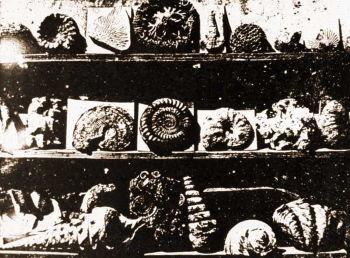

The Artist's Studio is widely considered the first successful daguerreotype. Natural light emanates from a window, casting its dramatic shadow across the artist's plaster-casts and other effects. There is a discernible romanticism in Daguerre's photograph in the way that it intones a direct link between photography and a traditional still life painting. Indeed, while it is generally agreed that Daguerre lay the foundations for the revolution in photographic reproduction, the image points in fact to something more modest in Daguerre's ambitions.

Daguerre, who was by now well known for his diorama exhibitions, was not without his distractors, many of whom harboured worries about the seemingly incessant march of industrialization. Concerns about the use of optical instruments and their threat to the traditions of history and genre painting sat within these wider anxieties. But this apprehension distracted from the fact that Daguerre was primarily interested in producing unique (rather than multiple) images, albeit that they would be rendered scientifically, on a silver-lined copper plate, rather than on linen or canvas. His photographic experiments were in fact extensions of his diorama paintings in the way that Daguerre was pushing for ways of better capturing subtleties and variations in light. It was only in the final printing process that these nuances in lighting became diffuse and Daguerre's still lifes provided the template, rather, for a role for photography that would allow for the dissemination (and subsequent analysis) of museum objects and artefacts.

Copper plate - Société Française de Photographie, Paris

Boulevard du Temple, Paris

Given the length of exposer times (typically 10 to 15 minutes), and the bulky and nearly immobile equipment, daguerreotypes were usually confined to the studio: still lifes, portraits or, in this iconic example, a street scene captured from the window of Daguerre's own studio. In the beginning, the world had to stand still in order to be photographed and Daguerre produced many still lifes and images of roof tops. One can see that there is no evidence of traffic on the busy boulevard while the only trace of human life is seen in the lower left of the frame where a shoe-shiner and his customer have remained immobile long enough to leave the only permanent human mark on the copper plate.

Daguerre made various views of the Boulevard du Temple and these were presented to several courts of Europe as evidence of his discovery. The scientific community was astounded at the detail in the images. On seeing the first results of the daguerreotype in 1839, La Gazette du France declared that photography was such a significant invention that it "upsets all scientific theories on light and optics, and it will revolutionize the art of drawing"; Daguerre, it continued, had for the first time in history created a "fixed and everlasting impress that could be taken away from the presence of the object". The artist Paul Delaroche seemed to be in full agreement with the Gazette's assessment when he lamented, "from this day, painting is dead".

Copper plate

Early photograph of United States Capitol, Washington, D. C., east front elevation, 1846

Plumbe was a Welsh engineer whose family had emigrated to the United States in 1821. He was an impassioned supporter of the importance of railways to the economic growth of a fledgling nation and when the daguerreotype reached America in 1840 he saw a brand new business opportunity to help fund his vision of railways expansion. Barbara Natanson, Head of Reference for the Print Division of the Library of Congress, noted, that "not only did Plumbe hear of and see a working daguerreotypist, but [he] envisaged the potential of photography establishing a network of 27 working studios that would take portraits as well as selling pictures and offering training. He also submitted several patents related to the Daguerre process and is thought to be the first photographer to franchise his studios".

On January 29, 1846 the United States Journal reported that "Mr. Plumbe's National Daguerrian Gallery at Concert Hall, is an establishment whose superior merits are well deserving the notice of all who feel an interest in the beautiful art of Photography [...] We are glad to learn that this artist is now engaged in taking views of all the public buildings which are executed in a style of elegance, that far surpasses any we have ever seen [...] It is his intention to dispose of copies of these beautiful pictures, either in sets or singly, thus affording to all, an opportunity of securing perfect representation of the government buildings".

Natanson comments that the Library of Congress holds a number of portraits from Plumbe's daguerreotype collection but his architectural photographs are of the greatest historical significance. His photographs of the Capitol Building were very likely the first and were taken before the 1850s which saw the expansion of the building through the addition of two new wings and the iconic dome. Natanson says of this image that it "is classically composed seeking to highlight the grandeur of the building from an elevated perspective, playing on the symmetry [and showing] an amazing amount of [picture] information". (Sadly Plumbe hit financial troubles in the late 1840s and was forced to sell his studios. He never realized his dreams for railroad expansion and committed suicide in 1857.)

Copper plate - Print Division, Library of Congress, USA

Burial site of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Clay, Jr.

War photography has a rich and morally complex history. Associated chiefly with documentary and news reporting, early nineteenth century images of war, such as those produced by Matthew Brady during the American Civil War and Roger Fenton during the Crimean War, benefitted from rapid technical advances in glass plate negatives that allowed for the mass-reproduction of their images.

The very first known photographs of war were, however, daguerreotypes (which produced a single mirror-like positive image that could not be mass-reproduced) made during the Mexican-American war of 1847. An unnamed American photographer made a series of some fifty daguerreotypes which captured scenes from the war in Saltillo (Mexico). The series featured portraits of military personnel, landscapes and, as is the case here, a Lieutenant's burial site. But, as the historian Megan O'Hearn observed, "While the images provide insight into daily life on the periphery of the war, they are especially notable for what they do not depict: in them, we see neither active battles or wounded and dead bodies, nor the idealization and glory sometimes associated with war".

The photographer's subject choices would have been determined by two external factors: his personal safety and the manifest limitations of his bulky equipment. Indeed, the cumbersome and fragile daguerreotype process insisted that the "world stood still" while it captured its pictures and so daguerreotypes could not claim to be the natural heir to war drawing and painting which typically showed acts of heroism on the battlefield. But, as O'Hearn points out, "the lack of action or heroism found in these anonymous photographs represented a departure from tropes of war imagery that would redefine war as seen by the public". Indeed, for all their lack of mobility, the first daguerreotypes effectively introduced the new age in visual representation in which the realities of war would be made increasingly vivid to those back home.

Copper plate - Amon Carter Museum of American Art

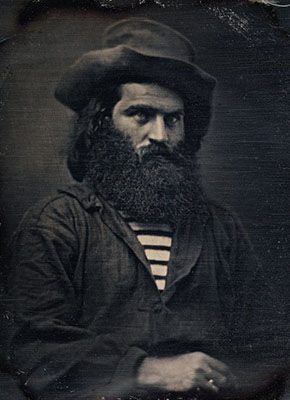

Portrait of an unidentified man

There was a different perception of what the daguerreotype was in America and Europe. The French had offered Daguerre's invention to the world as a scientific device - the nineteenth century French poet Charles Baudelaire even declared that photography was "the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies" - that produced flat results that were manifestly inferior to the best painted portraiture. In America, the daguerreotype was seen rather as a way of making portraiture more accessible with the sitters able to flaunt (or exaggerate) their social status. However, when gold was discovered in San Francisco in 1848, the daguerreotype showed that photographic portraiture could, given a different set of social circumstances, be more provocative. Indeed, according to the director of the Canadian Photography Institute, Luce Labart, the gold rush portraits "disrupted common thinking about photography history" and that the "technology of the daguerreotype was incredible [with a] sharpness [that] is barely equalled today".

With the Californian gold rush, prospectors (the "forty-niners" as they became known) flocked to the San Francisco area in search of their fortune. Some local communities descended into near lawlessness with swindlers and racketeers operating out of Boomtowns that disappeared just as quickly as they had arrived. The "forty-niners" were then a hardened bunch who came, in the words of Labart, to epitomize "the American Dream: starting over from nothing, powered simply by an appetite for wealth attained quickly through bold actions and sheer luck".

Referencing the detail of the portraits themselves, Lebart observed in the forty-niners a "hardness in their eyes" and through their daguerreotype portraits "affluence had [a] new iconography [as] the aristocrat gave way to the bandit, equipped with his aggressive toolkit [of] pistols, knives, and shovels". Speaking of this image in particular, Lebart observed a look that was "subversively defiant [and] disarmingly modern" in the way that his "debonair foulards, [his] manicured beard" and his "wide-brimmed hat" gave him a look that comes close to "that of a contemporary hipster".

Copper plate - Canadian Photography Institute, Vancouver, British Columbia

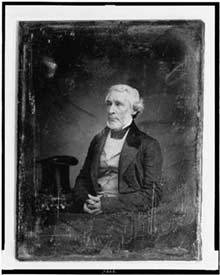

Self Portrait with a Daguerreotype Camera

Wetherby began his career as a commercial portraitist around 1835 and he, with the likes of Erastus Salisbury Field, were amongst the first in the United States to spot the business potential for the daguerreotype. Wetherby worked in and around Boston before relocating, via Louisville Kentucky, to Iowa City in 1844. While in Boston he implemented what was at that time an ingenious time-saving technique for making portraits: he asked his sitters to pose for his daguerreotype from which he would then compose their portrait at his own leisure (it is known that Field would even piece together daguerreotypes to be copied as group portraits). It is thought that this self-portrait, in which Wetherby is pictured with his own daguerreotype, was the painter's blueprint for just such a purpose.

Both Wetherby and Field have been claimed for the American Folk Art movement which writer and curator Holger Cahill had described as an earnest, non-academic, art form that celebrated "the simple and unaffected childlike expression of men and women who had little or no school training in art". Indeed, Wetherby (like Field) was known for his flat, "beginners" portraits which was the preference of his ordinary paying clients. But the daguerreotype had a wider function within the 19th century folk art tradition. As historians Floyd and Marion Rinhart explained, "the charming simplicity of American [folk] art exerted a powerful influence during the daguerrean era". Indeed, Folk Art was reproduced by daguerreotypes for both public and private viewing and for the purposes of posterity, advertising, and even insurance. Speaking specifically of Folk Art portraiture, the historian Laura Laubenthal noted that the photographic copies "did not require a large amount of skill and choice on the part of a daguerreotypist to reproduce them [and the] best way to capture a successful likeness of a painting was to position it squarely in front of the camera in an environment with equal, diffuse lighting to prevent glare".

While in Louisville, the Louisville Dime newspaper printed the following appraisal of Wetherby's new working technique: "We had yesterday afternoon, the opportunity of spending a few moments in the studio of Mr. Wetherby, on Market Street. He had just finished likenesses of several of our fellow citizens, and for true reflections of the originals, faithfulness of expression and beauty of finish, we confidently pronounce them unsurpassable. Mr. W is an artist of no ordinary merit, and we hope our friends will evince their appreciation of his talents by liberally patronizing him, and thus secure his permanent location here".

Copper plate - Print Division, Library of Congress, USA

Heirloom Harvest

Speaking in 2016 to Chelsea Matiash of TIME magazine, the photographer Jerry Spagnoli speculated that there were no more than 15 to 20 people working "seriously or routinely" with the daguerreotype process but that it would always "endure as an art form" in the same way that there "will always be people [...] who want to make oil paintings". For his part, Spagnoli, who had been working on an ongoing series he called The Last Great Daguerreian Survey of the Twentieth Century, described how it had taken him "perhaps a dozen years to really, finally put together a way of making daguerreotypes" and that when a photographer produces their own equipment "from scratch" (as he had) it affords them the liberating "ability to control the image that [he or she doesn't] have with industrialized photography".

Spagnoli had conceded that his daguerreotype came with "idiosyncratic limitations inherent in the technology" but that the "slow exposures, small size, limited color sensitivities, temperamental chemical reactions and the difficulties in viewing the image on a sheet of polished silver [combined] to present the viewer with the experience of having to negotiate the reality depicted". For Spagnoli the daguerreotype was "inviting in its straightforwardness" but that the resultant image "demands compromises from the viewer" in the way that it asks them to think flexibly about "what is and is not the truth in a documentary photograph".

Spagnoli's Heirloom Harvest project was conceived over a fifteen year period where he visited Amy Goldman's Hudson Valley farm - who was "the world's premier vegetable gardener" according to the New York Botanical Garden. Goldman describes the farm as being about "the pleasure of cultivating the land [and] preserving our agricultural heritage, and the beautiful and unique heirlooms that truly are organic pleasures". Springer's goal was then to "preserve these cherished varieties in another way - with the historical daguerreotype process, producing ethereal images with a silvery, luminous depth and a timeless beauty, underscoring the historical community and value of knobbly gourds, carrots fresh from soil". In this way, one can say that Spagnoli had revived in the daguerreotype what was, under its inventor's initial intention, a means by which one might objectively document the world in which we live.

Copper plate

Biography of Louis Daguerre

Childhood and Education

Born in 1787, in Cormeilles-en-Parisis, France, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre was raised in a well-to-do middle-class family. Louis's father was a committed royalist and, despite the onset of the French Revolution, he even named one of his daughters after France's condemned last queen, Marie Antoinette. The country's political upheaval meant that Daguerre's schooling was littered with interruptions. He managed to develop his talent for drawing however, and aged 13 Daguerre became apprenticed to an architect (it is also thought that he worked in some capacity as an inland revenue official during the same period).

At the age of 16 Daguerre moved to Paris where he studied and practiced panoramic painting for operatic productions under I. E. M. Degotti at the Paris Opéra. Before long, Daguerre had graduated to lighting director for several Parisian theaters. Daguerre also gained notice for his dancing skills and worked as a stage extra at the Opéra. But it was as an artist for theatrical scenery that he truly excelled. He earned a reputation for atmospheric landscapes and night effects which he demonstrated to novel effect in prestige productions such as Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp.

In the spring of 1821, Daguerre and the French panorama painter Charles Marie Bouton had come together to invent the diorama theater. The diorama was billed as a "scenographic entertainment" that took place in a specially designed theater. Accommodating as many as 350 patrons at a time, audiences would view translucent landscapes and architectural views, hand painted on linen, and brought to life by deep perspective and crepuscular lighting effects. Color filters were employed in such a way as to simulate movement. The spectacle was also enlivened with sound effects, stage props and sometimes even through the placement human figures. The diorama was a public and critical success with audiences willing to accept the illusion that they were viewing living scenery. Though some commentators have cited the diorama as an early forerunner of cinema, diorama productions lacked any kind of narrative impetus which allowed instead for feelings of romantic contemplation amongst its audiences.

Most patrons would stand (though there was limited seating) for a show that ran between 10 to 15 minutes before the image would rotate, on a huge floored turntable, to reveal a second painting of similar dimensions (some later dioramas even featured a third painting). Daguerre opened the diorama theater in Paris in 1822 and his second theater opened in London's Regent's Park in the fall of 1823. After a decade or so of success, Daguerre ran into financial difficulties. Dioramas were costly to produce, their novelty was on the wane, and an outbreak of cholera in Paris crippled ticket sales in the French capital. By the mid-1830s Daguerre faced commercial ruin.

Daguerre had been closely following scientific developments in photography since the late 1820s. He was looking for a way of incorporating mechanically produced images into his diorama system (Bouton had abandoned his involvement with the diorama and Daguerre saw photography as a potential means of replacing him). He had made the personal and professional acquaintance of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce who, in 1826, had created the world's first photograph through his heliographic process. The heliographic technique used a photograved plate method to fix an image (through a camera obscura) and from which one could then take multiple prints. The primitive heliographic process required excessively long exposures and developing time and lacked fine picture quality. This led the two men to develop a more advanced method which they called the physautotype. The physautotype, which they unveiled in 1832, involved covering a polished plate with an alcohol and lavender oil resin solution which was then exposed to sunlight and developed in the fumes of turpentine. The final results proved to be somewhat erratic, however; often producing distracting positive/negative effects.

Mature Period

Niépce died in 1833 but Daguerre pushed ahead with their earlier experiments and in 1835 Daguerre made his breakthrough. Having placed a highly polished, mirror-like, silver coated copper plate (exposed through a camera obscura device) in a lightproof chemical cupboard, he removed the plate 20-30 minutes later to find that the image had developed. Having examined the cupboard he noticed that it housed a broken thermometer and that the mercury vapor must have allowed the image to develop. Daguerre had still not solved the puzzle of how to fix a permanent image, however. The fixing process was only achieved when he realized that he could remove the silver iodide from the copper plate with a simple sodium thiosulfate (salt based) solution. Daguerre had advanced Niépce's initial process -- to justify naming as a new process, the daguerreotype (he reduced exposure times from fifteen to three minutes and developing time to thirty minutes). It would prove to be the first commercially viable form of photography.

Although daguerreotypes predated the negative sheet, they could be copied by a process of "redaguerreotyping" the original plate. Copies of originals were also produced through lithography and engraving while painted portraits based upon daguerreotypes began to appear in popular publications. The first daguerreotype cameras, meanwhile, were custom made by opticians, instrument makers and even by the photographers themselves. The most popular style of camera was a sliding-box device with the lens positioned in the front of the box. A second, smaller box was placed in the back of the larger box while focus was achieved by sliding the rear box backwards or forwards. This process produced a reversed image (though some more sophisticated cameras were fitted with a mirror to correct the reversal). It was only when the sensitized plate - which could vary in size: whole, half, quarter, sixth, ninth, sixteenth - was placed in the camera that the lens cap would be removed and the exposure achieved.

Daguerre formally presented his invention to the Académie des Sciences on January 9, 1839. His work made such an impression many eminent scientists of the day travelled to Daguerre's studio to see demonstrations. The American inventor of the telegraph, Samuel F. B. Morse, was moved to comment on the daguerreotype's picture detail: its "exquisite minuteness of [...] delineation" as he put it. On January 9, 1839 a full account of the daguerreotype was presented to the Académie by the eminent astrologer and physicist François Arago. Daguerre's patent was acquired by the State, and, on August 19, 1839, the French Government announced that the daguerreotype would be offered as a gift "Free to the World". Daguerre himself had registered the patent for England one week earlier (August 12) and thereby stalling the development of daguerreotype photography there (Antoine Claudet, a student of Daguerre's, was amongst the very few people licensed to take daguerreotypes there).

Once the daguerreotype had been licensed in Britain, a new, somewhat macabre, genre emerged. The so-called "post-mortem" daguerreotype became popular in Britain (and in America) and was seen by many Victorians as a way to filling a yearning for commemoration, remembrance and spirituality. The daguerreotype allowed parents and relatives to possess affordable "spectral", or "post-mortem", photographs which captured intimate images of deceased - loved ones (usually children amongst whom mortality rates were highest). Daguerreotypist were sometimes even instructed to ensure that the bodies' eyes were opened, or else, eyes might be painted onto closed eyelids, to give the illusion that the corpse was still living.

Late Period

In honor of his invention, the French government paid Daguerre an annual stipend of 6,000 francs which he lived off with the insurance payment he received from a blaze that destroyed his theater in 1839. The heir of Niépce's estate, Isidore Niépce, was also granted an annuity of 4,000 francs by the State. Daguerre was awarded the French Legion of Honor in recognition of his achievement and was made Honorary Academician at the National Academy of Design in the same year. Daguerre was described as a shy and modest speaker but he offered demonstrations and classes, and even published a brochure on the mechanics of his invention. A company was created to manufacture the equipment for making daguerreotypes, with a share of the profits going to both Daguerre and Isidore Niépce. But as the daguerreotype grew in popularity around the world, it came down to others to advance Daguerre's original design.

Having effectively retired, Daguerre returned to his first passion and spent the last decade of his life painting diorama-like tableaus for local churches in and around the Paris suburb of Bry-sur-Marne. He died there of a heart attack on July 10, 1851, aged 63.

The Legacy of Louis Daguerre

Although millions of daguerreotypes were produced worldwide, Daguerre's system had become all-but obsolete by the mid 1850s. William Fox-Talbot's "sensitive paper" based calotype process had emerged as its chief rival during the 1840s and the latter's faculty for duplication finally won out over the vastly superior picture quality of Daguerre's invention. But by then the Frenchman had already put his indelible stamp on the age of modernity. By the dawning of the twentieth century, photography had become so commonplace almost anyone could make their own pictures and create their own personal histories. Meanwhile, the Frenchman's invention provided the template for an underlying aspect of the modern age: the documentation and recording of things and peoples as part of a larger social project of classification and ordering.

Daguerre saw his invention first and foremost as a scientific development. Indeed, when the Eiffel Tower was built in the late 1880s, his name was inscribed on its base next to those of 71 other influential French scientists and inventors. The daguerreotype lent support to advances in medicine, astronomy, anthropology and archaeology. Yet its impact upon the development of the visual arts proved most profound. Liberated from the necessity to record the world literally, artists entered a modern period defined by an unprecedented level of formal experimentation. As for the history of art photography, then one need look no further than the Straight Photography of Paul Strand, the collective efforts of Group f/64, the portraiture of August Sander, and the industrial recordings of Bernd and Hilla Becher, to find a direct lineage back to the model of the daguerreotype.

Influences and Connections

- I. E. M. Degotti

- Pierre Prévost

- Joseph-Nicéphore Niepce

- François Arago

- Samuel Morse

- Antoine Claudet

-

![Romanticism]() Romanticism

Romanticism - French Panoramic Painting

-

![August Sander]() August Sander

August Sander -

![Ansel Adams]() Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams -

![Bernd and Hilla Becher]() Bernd and Hilla Becher

Bernd and Hilla Becher - Jerry Spagnoli

-

![William Henry Fox Talbot]() William Henry Fox Talbot

William Henry Fox Talbot - Samuel Morse

- Antoine Claudet

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI