Summary of Peter Doig

Peter Doig went from being an artist whose peers were too embarrassed to show alongside him, to possibly the most internationally loved painter of our time. He is a leading figure in contemporary art's 'return to painting' and is particularly responsible for re-inserting magic, narrative, and lyricism into painting today.

Doig is a meticulous colorist, who often uses uneasy, disquieting color combinations to create simultaneously charming and foreboding landscape paintings. Doig similarly combines seemingly incongruous, disparate reference points in his work often, inserting images from his own lived experience, film, art, and literary histories together in one composition.

Accomplishments

- Doig's paintings almost always contain human figures, although they are often partly obscured, hidden, or dwarfed by their environment. He rejects the split between figurative and abstract painting, however, and uses recognizable tropes of abstract painting - such as the dot or splatter - in the service of representation or suggestion - as in his snowscapes.

- Doig uses color chaotically and extremely effectively. His palettes can be subdued, cool, warm, or bright, but he is unparalleled in his understanding of how to (un)balance a composition via color. Complementary colors, sickly greens, sentimental pastels, and uncompromising reds all feature heavily, demonstrating a boldness with color that is unique in his generation.

- Magical Realism refers to a genre of literature and art in which everyday situations are interrupted, or mixed with, supernatural, spiritual, or other unlikely and uncanny events, environments, and characters. Doig has developed a magical realist painting style, which has some resonances with Surrealism, however is particular in its suggestion of narrative, character, and conflicting worlds. Doig combines imagery from multiple sources - film, art, and literary references as well as his own memories - to create these part realist, part magical scenes in his paintings.

Important Art by Peter Doig

Milky Way

In this mesmerizing canvas, pinpoint stars share a black and blue skyscape featuring a cloudy Milky Way. From the horizon a stretch of trees grows, glowing alien and coral-like, waving into the air as if in water. They are reflected beneath on a still black lake in which floats a lone girl in a canoe, her tiny body enhancing the painting's sense of scale.

The dreamlike work references Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night, produced a century before as an hallucinogenic, emotive, portrayal of van Gogh's view from the window of his room at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole lunatic asylum. The piece also references a number of 21st Century elements, with its echoes of current literature and film combined with the artist's own experience and imagination, as is his signature style. Doig said: "The tree line is a mixture of what I could see from my working space in my parent's barn and other sketches I made of northern-looking pines and dying trees. The idea was the trees were illuminated by city light or artificial light from afar - I had just read Don Delillo's White Noise (1985) that influenced the light in these paintings as well." The girl slumped in the canoe references the final scene of Sean S. Cunningham's 1980 horror movie Friday the 13th in which an exhausted young female protagonist boards and then falls asleep in a canoe on an otherwise huge empty lake. The eery canoe in this would mark the entrance of a motif that would appear again and again throughout his work.

This mode of combining reality, memories, fictions, and images from film and photography became Doig's trademark style and marks a bold integration of postmodern pastiche and collage sensibilities with traditional painting and historical reference points.

Oil paint on canvas - Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Charley's Space

On a snow-capped hill sits a large wooden house. Its roof is dusted with snow and there are dark forests in the background. On the right of the canvas a figure, which is cut off in the middle by the painting's edge. The bottom two thirds of the canvas are filled with a snowy, sometimes colorful, landscape. This work is rich in colors, textures and full of visual interest, but it is also obscure and hard to read. Much of the composition is overlaid with a large, floating orb.

This piece was begun during Doig's final year at Chelsea School of Art and would come to represent the beginning of the snow scene motif that would dominate much of his art.

Katharine Arnold of London auction house, Christie's, said: "In taking up archetypal images of Canada's landscape, Doig sought to distance himself from its specifics. These were not paintings of Canada in a literal sense, but rather explorations of the process of memory. For Doig, snow was not simply a souvenir of his childhood, but a conceptual device that could simulate the way our memories may be transformed and distorted over time." "Snow draws you inwards," Doig once said, which is why he so often used it as a device in his work, encouraging viewers to enter into his own remembered and filmic landscapes.

The circle in the middle of the piece is a visual reference to the opening scene of Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941), in which a flashback shows the protagonist (now on his deathbed) in an ambiguous snowy landscape. The circle also resonates with a number of theatrical and film devices: the spotlight, camera lens, etc. and this painting deftly harnesses the nostalgia, melancholia, and emotion of filmmaking, while amplifying the medium's ambiguity and mystery - this painting is a still moment that will not be explained at some other point in the narrative.

The snowflakes are both figurative and abstract, and play with mark-making techniques to show how a painter might think about both snow (descriptively) and the colored dots of an abstract composition (formally). The complex, yet whimsical, relationship between form, brushwork, and content in this work is an important moment in contemporary painting.

Oil on canvas - Whitechapel Gallery

Blotter

In Blotter we see a gloved figure standing on a sheet of frozen ice, watching his own feet as he appears to stamp in puddles, making ripples spread about him. His reflection is visible beneath and he is backed by a snowy bank, and higher up, a darkening forest. The movement on top of the ice is mesmerizing and the figure is totally absorbed in his action. The ice is rendered in calming purples, grays and blues.

The title referred to the process of building up color - literally soaking paint into the canvas - but also to the experience of being completely absorbed in a place or landscape. To start, Doig took a photo of his brother on ice onto which he had pumped water to create more interesting and vivid reflections. Doig was fascinated by the use of reflection in film, which is often used to represent an entrance point into another world. In this piece he reference's Jean Cocteau's 1950 film Orphée.

Additionally, blotting paper can be used to carry LSD, a drug that Doig took as a teen. Art critic Sean O'Hagan said: "A painting like the knowingly titled Blotter is charged with that heightened, fractured, but pinpoint-clear way of seeing that anyone who has taken the drug will immediately recognize." This was what Doig was trying to achieve with his work; he wanted the viewer to experience states of minds that are hard to describe.

Blotter won the first prize in the 1993 John Moores Painting Prize exhibition, representing a turning point in Doig's career, and an appetite for this strange and enticing form of Magical Realism.

Oil on Canvas - The Walker Art Gallery

Canoe Lake

This canvas features a green canoe floating on a yellow lake. The colors are acidic and sickly. A feminine figure slumps in the boat, as her hand dangles into the water, meeting its reflection. Behind the lake, reeds reach upwards.

This work was one of seven canoe paintings that would become one of Doig's trademarks. Canoes have long been used to symbolize Doig's childhood home, Canada, in art and imagery, but Doig also favors boats as they create a suggestion of hidden depths. He said: "Because you think of floating. There is a lot more below". Art critic Adrian Searle saw something darker in the canoe motif: "Figures in canoes and boats drift through Doig's show, as though - a disconcerting thought, this - biding their time, waiting to ferry us to the underworld." In either interpretation, the canoe is a precarious vehicle for travelling the unseen waters of Doig's paintings.

As with Milky Way (1989-90), the motif of the girl in the canoe is borrowed from the ultimate scene of slasher movie Friday the 13th. He said: "People thought it was about the horror in the film. It was never about that. It was more about the mood - an image of a woman in a boat. Why is the woman in the boat? Why is her hand dangling in the water? It's almost as if she's fallen asleep and is in the process of waking up."

Of course, the in-between-ness of the half sleeping girl in the canoe is itself a horror trope, with links to the undead, to death, and to ghosts roaming bodies of water. Although Friday the 13th's girl protagonist is ostensibly a survivor of the film, Canoe Lake also cites John William Waterhouse's The Lady of Shalott (1888), the famous Pre-Raphaelite rendering of the suicidal protagonist of Tennyson's eponymous poem. The painting's unnerving imaging of a non-site (which simultaneously exists in our world, the underworld, the world of the horror movie and that of the Pre Raphaelites) remains a troubling testament to the power of painting on the human psyche today.

Oil on canvas - The Saatchi Collection

Echo Lake

In the middle of this surreal landscape a police car stands as an officer approaches the starlit lake in the foreground, his reflection visible beneath. He is peering out towards the viewer with his hands aloft as if he is shielding his eyes to see into the darkness. His mouth is open as if he is calling out. Eerie forests absorb the light, and horizontal bands of color in the middle of the piece are muddy and dark, while the greens of the trees behind are ghostly.

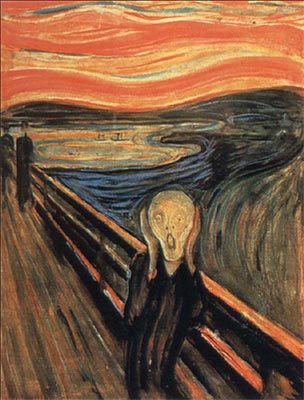

The piece's darkness, the figure's pose and the eerie background all refer back to Edvard Munch's Ashes (1894), painted more than 100 years earlier. Doig said: "I looked at the coloration and the expression. Also I felt, she's looking out on to a lake. In my painting, a policeman looks out across the lake towards the viewer, the screamer. I took that directly from Munch."

Nicholas Serota, Chair of Arts Council England, said Doig's paintings "have a kind of mythic quality that's both ancient and very, very modern. They seem to capture a contemporary sense of anxiety and melancholy and uncertainty. Lately, he's gone more toward the sort of darkness we associate with Goya." This is evident here. The piece is menacing, asking more questions than it answers. Again we see the reflection motif, bringing up thoughts of drowning in the unknown. The low vantage point suggests we, the viewer, are in the lake, perhaps floating in one of Doig's famed canoes. We are far enough away to be unable to hear the officer's shouts of warning or rescue. Doig was always looking to produce "an image that is not about a reality, but one that is somehow in between the actuality of the scene and something that is in your head". By positioning us, the viewer, as the "screamer" in his own painting, Doig again centralizes an embodied, emotive experience of his work, an ideal that had long been absent in discussing important aspects of contemporary art's relationship to its audience.

Oil paint on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Two Trees

At three and a half meters wide, this piece is so monumental that when it was installed in the South London Gallery, windows had to be removed to get it in. The canvas depicts three young men, standing in front of the ocean as the rising moon or setting sun brightens the horizon.

The piece took six years to complete and Doig worked on it up until the moment it was delivered to the gallery. All of the artist's signature motifs are there; water, reflection, a solitary boat, snowfall, vivid color, and mysterious messages, but here the violence hinted at in previous pieces becomes more pronounced, literally foregrounded in the painting.

On the left a hockey player in a helmet wears a camouflage uniform, which ironically functions to make the player, holding his big stick, even more visible. In the middle, a young man's head is either dressed in what could be a knitted hat or showing an exposed brain. This figure referred to a killing that took place in Doig's own Trinidad neighborhood, according to press reports at the time. On the right a man films a scene with a camcorder - signposting events in which onlookers film scenes of death and devastation, rather than stepping in to help.

Mark Hudson, art critic, said: "This is art that's designed to resonate in the mind as much as the eye: a sumptuous Magic Realism for the digital age, with a random, search-engine-like connection-making rendered in oil painting that delights with the sheer richness of its surfaces."

Oil on linen - Michael Werner Gallery

Biography of Peter Doig

Childhood

Peter Doig was born in Edinburgh in 1959 to Mary and David Doig. At the age of two, his family moved to Trinidad where his siblings Andrew and Sophie were born. When he was seven, the family moved to Montreal, Canada, due to his father's job as a shipping merchant. He was sent to a Scottish boarding school from the age of 12 thanks to money left by a great-aunt, but after three years of unhappiness, his parents let him come home. His mother had been worried he'd be expelled; he was "an adventurous, free spirit" in her words. The family moved to Toronto where Doig struggled at school. He was not an academic child and preferred to spend time with friends, listening to music, smoking weed or taking LSD.

This transitory childhood robbed him of a sense of belonging, which lasted throughout adulthood. He never lived in a house for more than three months at a time. He said: "That's all I knew and that's why I don't really belong anywhere. Then again, I do feel Scottish in some way. Maybe it's to do with visiting my grandparents there every summer as a child, but I am aware of my Scottish ancestry. It's there all right, but it would be pushing it to label me a Scottish painter. Or, indeed, an anywhere painter."

Early Years and Training

By the age of 17 Doig had dropped out of school to take up various jobs. It was not until he found himself lonely and bored working as a laborer on a gas drilling rig that Doig picked up a sketchbook for the first time. He had no real 'natural' drawing skill, but his father had been an amateur artist and his great-aunt a professional, so he decided on painting as a career, despite the fact that he was poor at drawing. In 1979, he took himself off to London to go to art school. He enrolled on a foundation course at Wimbledon College, where he met Bonnie Kennedy, who was to become his wife. The following year he enrolled at St Martin's, but he was held back by his lack of skill as a draughtsman. He recounted how one of his teachers held up a life drawing of Doig's, declaring it the worst he had ever seen. He learned to get round it through taking photographs, and projecting them onto canvas to paint on top.

He lived in King's Cross, which he described at the time as "a mad, rough place, full of oddballs and artists". Doig felt comfortable in the local scene and started hanging around with musicians and fashion designers. At college, he said, he "found his voice", despite being intimidated by his peers and the "general air of cool that hung over the place". He began his artistic career painting urban scenes, which he said were "less about making paintings and more about making images".

After he graduated, he moved back to Montreal where his wife, Bonnie Kennedy, had been offered a job at the fashion firm Le Château. They got married in 1987, and Doig worked designing film sets, but felt cut off from the community in London. He returned at the age of 31 to enroll on an MA course at Chelsea School of Art where he found an industry going through a huge change as the Young British Artists stormed onto the scene. It was here that he met lifelong friend Chris Ofili, who would go on to become the first black winner of the prestigious Turner Prize. They bonded through their love of painting, Trinidad, and music, and have been close friends ever since.

It was around this time that Doig realized he was doing something quite different from his peers. With the exception of Ofili and Jenny Saville, most of his contemporaries thought that painting was obsolete. Doig said: "I was out on a limb. My work looked very different to everything else on show and, not just that, but some of the artists did not want to show their work in the same space as me. They obviously thought my paintings were some sort of dreadful throwback or somehow not serious enough or absolute kitsch."

His work remained unpopular for a few years but in 1990 his career began to turn around when he won the Whitechapel Artist Prize and three years later the John Moores Painting Prize.

In 1992 the couple's first child, Celeste, was born, then Simone was born two years later. Doig was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1994.

Mature Period

In 2002 the Doig family - now comprising two more daughters, Eva and Alice - settled in Trinidad, inviting comparisons to painter Paul Gauguin, who moved from France to Tahiti. They had their son, August, there, and three years later Ofili moved to the island to join them.

By 2007 Doig had become Europe's most valuable living painter when his painting White Canoe (1990-91) sold at auction for a record-breaking $7.5 million. He held this record until Lucien Freud's Big Sue was sold to the London-based Russian billionaire, Roman Abramovich, for $33.6 million the year before Freud's death in 2011. Although the $7.5 million sale catapulted Doig into celebrity status, the sale troubled him. It was, Doig believed, a symptom of an art market gone mad. "I was absolutely shocked that someone would pay so much," he said, "but I was also struck by the pressure it put me under. To go into a studio and think you're going to make a painting that's going to make a million dollars or a hundred thousand."

Doig has dealt with personal difficulties in the past decade. In 2012 his 24-year marriage to Bonnie Kennedy ended. His father - to whom he was very close - died, and Doig was taken to court over a painting that had been falsely attributed to him - a complicated and protracted lawsuit that kept him out of the studio for months at a time. He had to prove in court that he was not the artist behind a bizarre desert landscape signed "1976 Pete Doige". The case took four years to conclude, and his whole family became involved before it was found that Doig had nothing to do with the work.

In 2015 he had another daughter, Echo, with curator Parinaz Mogadassi. He now lives in Trinidad where he leads a simple, healthy life. He spends his time working alone in the studio and to relax he kayaks, swims, plays ice hockey, and skis. He has set up a film club, along with Ofili, which meets in a large room next to his studio every Thursday night where he and friends drink beer, watch arthouse movies and talk about what they have seen.

The Legacy of Peter Doig

Defiant in the face of conceptualist, multimedia, deskilling practices, Doig's paintings use specific, autobiographical moments to connect with universal emotions in a mystical and intangible way. Unlike his YBA contemporaries, such as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst, Doig specifically worked to make his work appear handmade, creating a space for the artist's traditional skills to flourish in British contemporary art of the time and beyond.

Curator Keith Hartley said that Doig's work speaks to the question of whether painting still matters. Doig has answered it, Hartley said, by "looking back and realizing that there is a lot to be retrieved from the history of painting that can inform painting today. He has an extraordinary visual memory which coalesces with his personal memories when he paints. So, an incident that he witnessed can be transformed by the interaction of all these elements into a painting that possesses an extraordinary resonance." Doig's prolific painting career has ensured that questions of color, composition, and evocative figuration remain central to the work of young contemporary artists, especially painters.

Influences and Connections

-

![Chris Ofili]() Chris Ofili

Chris Ofili - Hurvin Anderson

- Michael Armitage

- Lisa Brice

-

![Chris Ofili]() Chris Ofili

Chris Ofili - Derek Walcott

- Lisa Brice

Useful Resources on Peter Doig

- Peter DoigBy Peter Doig, Richard Shiff, Catherine Lampert / March 17, 2017

- Peter Doig (Contemporary Artists)By Adrian Searle, Kitty Scott, Catherine Grenier, Hannes Schneider, Arnold Fanck / January 1, 2007

- Peter Doig: No Foreign LandsBy Stéphane Aquin, Keith Hartley, Angus Cook / October 31, 2013

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI