Summary of El Greco

El Greco's life and work were marked by a deep underlying devotion to God. Compelled as a young man to become an artist, he mastered a longstanding tradition of Byzantine icon art, yet by the time he eventually settled in Spain his inspiration was largely drawn from the burgeoning Italian and Spanish Renaissances. Although his early ambitions were to become a court painter, his individual style that began to emerge in Spain quickly catapulted him from the confines of any conventional school. He became vastly interested in the new Mannerist movement, a group who disavowed the mere imitation of nature in art, and instead sought to express the underlying psychological aspects of a work beyond its mythological or religious themes. These concepts informed a body of work that is deeply evocative of the Divine and universally noted for manifesting the spirituality that lay beneath all being.

Accomplishments

- El Greco is best known for his tortuously elongated figures painted in phantasmagorical pigmentation, which almost resembled chalk with its blunt vividness. Drawing upon Byzantine tradition while incorporating a Mannerist's veer from reality, these abstracted, expressionist forms established a new visual dialogue that broke away from traditional modes of representation in Classical art.

- The importance of imagination and intuition over subjective characterization was a fundamental principle in El Greco's style, allowing him the freedom to discard such classical criteria as measure and proportion. Instead, he employed techniques such as radical foreshortening to challenge perceptions of the norm.

- A tendency to dramatize rather than describe marks the painter's work, articulated through bold, unreal choices in color, and the juxtaposition of highlights next to dark, thick outlines. These jarring contrasts result in an emotional transference from painting to viewer.

- El Greco's work has also been cited as a precursor to Expressionism for its presentation of the emotional in ways that had not been articulated before. He is also said to have had an influence on the Cubists, most notably Pablo Picasso, because of the way his paintings reconsidered form and figure beyond literal reality.

Important Art by El Greco

The Holy Trinity

The Holy Trinity, painted between 1577 and 1579, depicts God holding a dying Christ in his arms, as they float amidst clouds in heaven, with the dove of the Holy Spirit flying over their heads. Surrounding them are six angels in colored robes, and behind them, coming from above is a bright golden light. The painting is part of El Greco's first major commission for the Church Santo Domingo in Toledo, and, as soon as it was completed it established him within the community as a revered artist. Today it is considered one of his masterpieces, and noted as one of Édouard Manet's favorite paintings.

This early example of El Greco's work presents a synthesis of the two major influences that define him: the Renaissance masters and the Byzantine iconic tradition. Although the composition shows affinities with the works of Michelangelo and Dürer, and both artists are believed to have been a profound inspiration for this painting, the work also already shows various unique attributes that defined El Greco's body of work and composed his signature language. Art historian Keith Christiansen claims that, "He made elongated, twisting forms, radical foreshortening, and unreal colors the very basis of his art." All of these aspects are present in The Holy Trinity: the brilliant and expressive use of color in the robes, the continuity between forms and substance in the intertwining of the bodies of the figures, the elongation of the figures, especially in Christ's body, and the imaginative dream like quality that defines the overall feeling of the painting. One of his main characteristic techniques is also already used in the work profusely, which is the use of highlights next to dark and thick outlines to create a profoundly dramatic effect.

A specific interpretation can be found in the colors employed, where the gloomy aspect of the clouds can be seen to represent death, opposing the golden rays above that symbolize the eternal; the two emphasize the duality between life and the ever after. Overall, this is the main interpretation of the work: an embodiment of the eternal as a reality thereby instilling a new sense of hope and devotion in the faithful.

Oil on canvas - Museo del Prado, Madrid

The Nobleman With his Hand on his Chest (El caballero de la mano en el pecho)

This painting is a portrait of a nobleman or knight around the age of 30, whose real name is unknown. He is dressed in traditional Spanish clothing holding a sword in one hand while the other is poised over his heart. Staring intensely at the viewer, he is portrayed in a manner that is profoundly realistic yet also imaginative. With an aspect deeply characteristic of El Greco's work, the depiction possesses specific technically accurate features such as the beard, combined with stylized elements, such as the elongated fingers and torso. The muted, dark colors and tones contrast greatly with the white of the ruffles. The dramatic use of contrast and light greatly enhances the emotional and psychological depths that define the subject.

Although El Greco was mostly known for his religious themes, he was also a prolific portraitist, known for capturing the character and personality of his subjects in an intuitive way. This painting is considered to be his most famous portrait. It is also an example of his breaking away from the traditional Renaissance style and his Byzantine background through a more Mannerist, imaginative mode. El Greco was known to claim that an artist "must study the Masters but guard the original style that beats within your soul," emphasizing the importance of establishing and being true to his own vision and individual artistic language.

This portrait can be seen as a direct influence on the portraiture works later developed by other art movements such as Expressionism. In a broader way, El Greco's ability to transform reality to expose an inner vision or inner world, can be seen as a precursor of Modern Art.

In this context, it is also of reference to Picasso's painting entitled Portrait of a Painter, after El Greco, from 1950, that can be seen as a tribute to El Greco's way of envisioning and understanding art, which established a great influence on Picasso from the very beginning of his artistic career. In the work, Picasso combined El Greco's use of dark browns and ochres with his signature Cubist language, echoing centuries later, El Greco's ever-present iconography.

The painting is featured in the cover of a Vangelis album entitled El Greco from 1998.

Oil on canvas - Museo del Prado, Madrid

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (El entierro del conde de Orgaz)

This large painting, three and half meters wide by almost five meters high, is universally regarded as El Greco's greatest masterpiece and most famous work. It was commissioned by the parish priest of Santo Tomé in Toledo, and is considered to be a prime example of Mannerism. Along with Tintoretto, Agnolo Bronzino, Jacopo da Pontormo, and others, El Greco is considered one of the main Mannerist artists. His contribution to the development of the movement is marked by visual compositions that moved away from an idealized perfection into a world charged with tension and emotional complexity through form, imagination, and expression.

El Greco referred to this painting as his 'sublime work.' The Burial of Count of Orgaz is a popular legend in Toledo of a pious and charitable man who left a large sum of money to the church after his death and was subsequently buried and escorted to heaven by Saint Stephen and Saint Augustine. The funerary scene is portrayed at the bottom of the painting, with the Count surrounded by the two saints, followed by other noble men and clergyman of the time in 16th century clothing, captured in a static way. It is contrasted with the celestial kingdom in heaven that includes Mary, Christ, God, John the Baptist, and the angels, who all observe the scene, depicted in a more organic free flowing way, so as to represent the intangibility and immateriality of spirit. The young boy at the left is said to be Jorge Manuel, the artist's son.

One possible interpretation that is in the juxtaposition of the worlds: the physical world of earth and the spiritual world of heaven, each portrayed in their own ways. Earth is captured in normal scale with more proportional figures, whereas heaven is composed of swirling clouds and abstract shapes, with a more intangible quality to the figures. This clear distinction greatly allows for two ideas: on the one hand a union between both worlds is proposed, on the other, the separation of the worlds is enhanced. Another interpretation is brought forth by art Historian Dr. Vida Hull who claims the painting represents "a visionary experience." In her view, the amorphous character and the elongation of the bodies all convey a profound otherworldliness, as it is the soul of the Count that is being brought up to heaven.

Burial scenes were often depicted as a main religious theme in art. Other notorious works of burials, painted after El Greco's, include the Burial At Ornans (1849) by Gustave Coubert, The Burial of the Sardine (c. 1812-1819) by Francisco Goya, and the Burial of St. Lucy (1608) by Caravaggio.

Oil on canvas - Iglesia de Santo Tomé, Toledo

Madonna and Child with Saint Martina and Saint Agnes

Madonna and Child with Saint Martina and Saint Agnes depicts Mary and the baby Jesus seated on clouds in heaven, accompanied by Saint Agnes holding a lamb on the bottom right and Saint Martina on the bottom left. The figures dominate most of this large-scale painting, intertwining with each other in a complex interdependent way. The painting was originally placed opposite another of El Greco's paintings, Saint Martin and the Beggar, in the Chapel of Saint Joseph in Toledo and represents a body of work made between 1957 and 1607 of various commissions characterizing his mature period.

This work is an example of his deeply expressive nature and stylized approach to form. The use of brilliant vibrant colors, that is also so characteristic of El Greco's paintings is very much present in the work, featuring the cloaks of the angels and Mary in deep reds, blues, and yellows. For El Greco, the use of color was considered to be a fundamental feature of every painting, much more than form, and he thought it was a profoundly complex issue claiming that he considered the imitation of color "to be the greatest difficulty of art."

One way of interpreting the work is brought forth by the novelist and art critic Aldous Huxley, when in 1950, he claimed that, "the intention of the artist was neither to imitate nature nor to tell a story with dramatic verisimilitude," but rather to create "his own world of pictorial forms in pictorial space under pictorial illumination ... using it as a vehicle for expressing what he wanted to say about life." In this perspective it is the underlying message, the portrayal of the spiritual realm as a real presence of the world, that grants the work its universal significance.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

View of Toledo

The painting depicts a view of the city of Toledo where El Greco lived for most of his life. The landscape is painted in a dramatic manner, with vivid vegetation in the foreground and tumultuous clouds that seem to be announcing a storm as background. The city is depicted with grey tones, as it sits at a distance at the top of the natural hills, leading down into the Roman Alcántara bridge. The buildings are depicted in a cloud-like form, an organically clustered agglomeration.

El Greco approached the subject in the same manner as he did his other works, drawing inspiration from reality but remaining untrue to it. He invented the scene in order to convey the emotions that he desired; besides the castle of San Servando being located correctly, all the rest of the buildings are derived from his imagination.

The portrayal of a landscape subject was an unusual subject for the time, especially in a Spanish context, which garnered El Greco consideration as the first landscape artist in the history of Spanish art. This particular rendition of the sky is one of the best known in Western art. It is the only surviving example of El Greco's landscapes and very little is known about its story, origin, or circumstances.

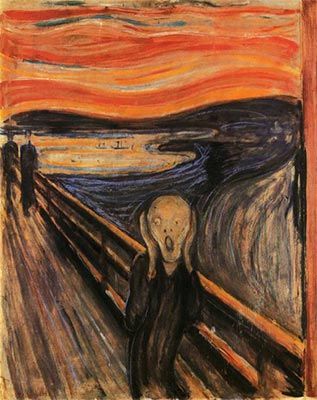

The imaginative language of the painting can also be seen as a direct influence on Expressionism. Both Edvard Munch's The Scream of 1893, with its dramatic flowing sky and clouds, and Van Gogh's landscapes such as The Starry Night painted in 1889, with its contorted vegetation and dramatic skies, can all be seen to further El Greco's viewpoint.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

The Ecstasy of St. Francis of Assisi

The painting depicts the ecstasy of St. Francis, a popular subject in classical art also depicted by Caravaggio in 1595, by Giovanni Bellini in 1475, by Giovanni Baglione in 1601, and various other notorious artists whom were all drawn to the story. It depicts the scene from the legendary life of Saint Francis of Assisi, a 12th century Italian saint, who two years before his death in 1224, embarked on a journey to Mount La Verna for forty days of fasting and prayer. One morning as he prayed, he went into a religious ecstasy and received the stigmata (the marks of Christ upon his body as he was nailed to the cross) by an angel or seraph. In the painting, El Greco portrays St. Francis in this exact moment with a face full of the emotions of devotion, pain, and surrender. In front of the Saint is a skull, usually associated with the Saint, and a symbol of mortality.

El Greco was fascinated with this subject, as it is generally sustained that his workshop possessed over a hundred representations of St. Francis. However in this painting, El Greco dispenses his usual light, colorful and bright representations, and creates an overall dark and somber atmosphere to re-create the painful and dramatic experience of the Saint.

Although the painting is also an example of Mannerism, its use of high contrast darkness and light seems reminiscent of another artistic language that can be associated to the dramatic works of Rembrandt in the 17th Century.

Oil on canvas

Christ blessing (The Saviour of the World)

This painting depicts Christ holding one hand on a blue globe, and gesturing to heaven with the other. There is a white light shining either from behind him or from within him, acting as a halo against the black dark background. It is painted in El Greco's signature fluid style and possesses a profound aesthetic and psychological force, mainly granted by the intense look of Christ's eyes that stare deep into the observer. The vivid bright red color of his robes deeply contrast with the subdued and somber color employed in the rest of the painting. As is characteristic of his body of work, the elongated fingers and torso, deeply inspired by Tintoretto and Titian, grant the painting a dreamlike quality that is both real and profoundly unworldly, seeming to make Christ belong, physically and metaphorically, to both worlds.

This work reflects a good example of El Greco's mode of combining a more Byzantine iconic tradition with the more humanistic approach of the Renaissance, while still rejecting an exact imitation of reality. As Art historian Keith Christiansen claims, "El Greco rejected naturalism as a vehicle for his art just as he rejected the idea of an art easily accessible to a large public. What he embraced was the world of a self-consciously, erudite style, or maniera," deeply associated to Mannerism. By denying the world around him and moving away from realistic and naturalistic languages, he embodies the realm of the spirit through movement and freedom of form in a symbolic and metaphorical way. In fact, El Greco is known for claiming, "The spirit of creation is an excruciating, intricate exploration from within the soul".

Oil on canvas - Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK

Laocoon (Laocoonte)

The painting portrays the myth of Laocoon, a Trojan priest who according to legend, warned the locals about the Trojan horse and also profaned the temple of God. As a consequence, giant serpents sent by the angry Gods killed him and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus. In the painting, the three are depicted in the foreground being engulfed by the large serpents. On the right, one of the sons appears to be already dead as he lies on the ground, whereas Laocoon and his other son fight for their lives. The background features the Trojan horse and the town of Toledo surrounded by trees in intense blues and greens. These vibrant colors of life greatly contrast with the muted grey palette used for the figures that symbolize death. The two figures standing on the far right are presumed to be Apollo and Artemis who observe the unfolding drama.

Art historian Keith Christiansen claims, "No other great Western artist moved mentally - as El Greco did," emphasizing the underlying psychological intention of the work. In this sense, the main interpretation that can be drawn is derived from the myth itself, that man is powerless and hopeless in the realm of the Divine and must succumb to his inevitable fate.

This work is considered one of the best examples of El Greco's later works, and the only of his known paintings that depicts a mythological theme rather than a religious one. Along with The Vision of Saint John (1608-1614), it is known for having a profound influence on the Expressionist and Cubist movements because of its intense emotional imagery and its vivid accentuation of individual form within the overall composition.

Oil on canvas - National Art Gallery, Washington DC

The Vision of Saint John

This large canvas is considered another one of El Greco's masterpieces. It depicts a passage in the Bible, Revelation (6:9-11), which describes the opening of the Fifth Seal at the end of time and the distribution of white robes to "those who had been slain for the work of God and for the witness they had borne." In the foreground, we see the elongated figure of Saint John, on his knees with arms wide open, as he implores to God above. Behind him is displayed a group of naked figures, reaching up to the heavens for their robes, some of which are white and others which are colored. These are the souls of martyrs who have been crying out to God for justice.

The painting is one of various works commissioned by Pedro Salazar de Mendoza, an admirer and collector, for the Church of the Hospital of Saint John the Baptist (the Tavera Hospital). El Greco died before he was able to complete the painting and it is said that there was an upper part to the painting that is missing, believed to have been destroyed in 1880. Rumors state that the missing part may have depicted the Sacrificial Lamb opening the Fifth Seal.

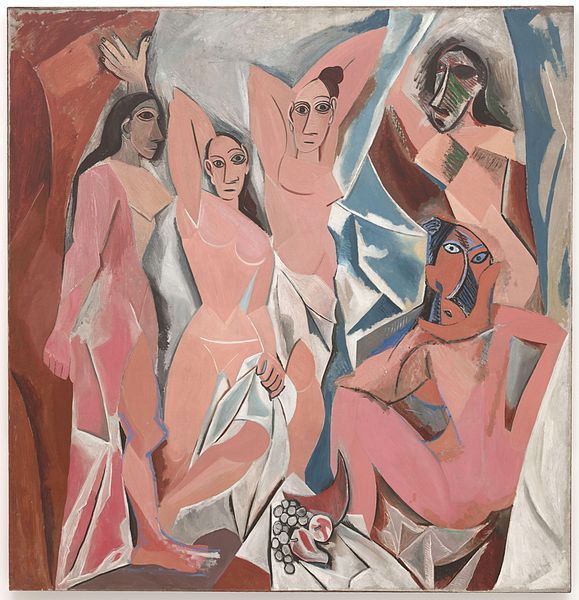

The work exerted a profound influence on Pablo Picasso, who is believed to have studied it profoundly using it as inspiration for the composition of his own masterpiece Les Demoiselles D'Avignon (1907). Connections can be drawn in the dynamic composition created between the various figures in both paintings.

Art critic Jonathan Jones, states that El Greco was "drawn to complexity, to obscurity, to sophistication," three characteristics that greatly define this work, and that he "spoke a messianic language of religious renewal." This renewal through faith is in fact, one of El Greco's main motivations, and is the prime underlying message of this work that emphasizes the salvation and protection of souls that are good.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Biography of El Greco

Childhood

Doménikos Theotokópoulos was born in 1541 in Crete, a Greek island that was part of the thriving Republic of Venice. Little is known of his childhood, other than the fact that he chose to be an artist at a very young age.

Education and Early Training

In his hometown, Theotokópoulos trained as an icon painter. The portraiture style was a popular means of depicting religious subjects in a static, devotional way. By the time the young artist was 22 years of age, he had become a master of this post-Byzantine type of art. In the years following his studies, he was commissioned to paint alter pieces for the local Orthodox churches.

Although the date is somewhat uncertain, it is believed that at the age of 26, Theotokópoulos traveled to Venice to pursue his artistic dreams, following in the footsteps of the artists that came before him. In Venice he found the opulence and inspiration he needed, surrounded not only by Byzantine art but also by the Italian Renaissance. He joined the studio of Titian, who was generally considered one of the greatest painters of the time. He began studying elements of Renaissance painting, especially perspective and figural construction, to learn how to depict complex narratives. However, as a young foreign painter his work was not well received.

Mature Period

After three years in Venice, in 1570, Theotokópoulos moved to Rome, where he lived in the quarters of the palace of a wealthy patron named Cardinal Alessandro Farnese. This position makes it clear that he was well connected, possibly recommended by a Venetian friend. Theotokópoulos joined the painters' academy and set up a studio with two apprentices.

It was in Rome that Theotokópoulos further developed his artistic skills and began to formulate a unique style. He drew upon the popular Renaissance style of the time but sought to distinguish himself by finding new ways to interpret the traditional religious subject matter. He found innovation in the Mannerists who were rejecting ideals of harmonious proportion, balance, static beauty, and naturalist presence. This resulted in works that contained both the agile, elongated, and romanticized figures and chromatic framework of the Renaissance with the violent perspectives, strange altitudes, and tempestuous gestures of the Mannerists filtered through his own prolific imagination and expressive view of life. The visual tension he managed to achieve through artificial distortion and unrealistic colors evoked a narrative drama, which lent a sense of emotional, psychological, and spiritual pulse to his paintings.

Although Theotokópoulos had joined the painters' Guild of Saint Luke and seemed to be "on the edge of a brilliant career in the city of the popes," as claimed by art critic Jonathan Jones, after six years in Rome, he still hadn't received any commissions. This is probably due to the fact that he openly criticized Michelangelo, who had died a few years earlier and was still well regarded in Rome. It is believed that he claimed he, "could replace The Last Judgment with something just as good, and more Christian."

His intense commitment to artistic development and understanding led him to Spain in 1577. First he went to Madrid, and then to Toledo, a profoundly commercial, historical, religious, and artistic center. It is generally accepted that it was here that he was named El Greco, 'the Greek,' by his friends. However, the name could have also been derived from his time in Italy, where it was custom to identify an artist by his place of origin. As he always signed his paintings with his full name in Greek letters, the name El Greco further emphasized the background he was profoundly proud of. Shortly after his arrival, he found himself surrounded by intellectual friends and generous patrons, finding the artistic respect he desired by receiving two major commissions for local churches.

This prolific artistic period also coincides with El Greco's conversion to Catholicism. Although other personal aspects of his personality are unknown, his utter devotion to creation is clear when he claims that he painted, "because the spirits whisper madly inside my head." El Greco wasn't only a painter who portrayed religious subjects; he was a profoundly religious man who lived within that spiritual world. This influence on his art was profound, in that it compelled him to articulate his art as an embodiment of a higher realm of spirit, repudiating the experience of painting as one of merely crafting a visually appealing piece. This lent to his position as a great modernist of his time. He was elitist and acted with superiority, considering "the language of art is celestial in origin and can only be understood by the chosen," and that he was created by God to fill the world and the universe with his masterpieces.

In 1578, he had a son named Jorge Manuel with Doña Jerónima de Las Cuevas. Although they were both officially recognized in letters and other documents as a couple, they never married. This unconventional approach has led to various speculations of an unknown previous marriage in Crete.

It is believed that at some point during his mature years, El Greco was commissioned to paint for King Phillip II, the richest and most powerful ruler in Europe at the time. This would finally give him the chance to become a court painter - his lifetime dream. However when he presented the works to the King, he profoundly disliked them and dismissed El Greco forcing him to return to Toledo.

Devoted to his vision, El Greco never changed his way of painting, no matter what type of opposition he encountered. Back home in Toledo however, he was happy to be met with the same appreciation and validation he had found before.

It is also known that in Toledo El Greco worked as a sculptor and an architect, however not many details of these forms of artistic expression exist. He was a man of extensive culture and knowledge, a Renaissance man, and his library is believed to have possessed all the classical Latin, Roman, Spanish, and Greek literature, including the architectural treatises of Vitruvies, Alberti, Serlio, and Palladio. Art critic Jason Farago further claims that, "El Greco was not a lone wolf or a hermit. He was a shrewd businessman and he had supporters, though nothing on the level of such hustling artist-politicians as Titian or Rubens."

Later Work

In 1585, El Greco moved to the medieval palace of Marqués de Villena, most likely in need of a larger painting studio. He enjoyed a stable social life, and was close friends with various scholars, intellectuals, writers, and churchmen. Between 1597 and 1607, he enjoyed his most active period of commissions, being contracted to paint for several chapels and monasteries simultaneously. This phase, considerable for its prodigious output, includes some of his most notorious works.

El Greco fell ill and passed away in 1614 while he was working on a commission for the Hospital Tavera. Although he did not leave a large estate upon his death, he had always enjoyed a comfortable life.

The Legacy of El Greco

El Greco is generally considered one of the leading figures of the Spanish Renaissance that defined the 15th and 16th centuries. Although at the time, due to his greatly individualistic expressive style, his art was received with much reluctance and confusion, he is now considered to be one of the "select members of the modern pantheon of great painters," as claimed by art historian Keith Christiansen, and is regarded as a true visionary artist that lived well ahead of his time.

His work found great appreciation in the 19th century, when a group of collectors, writers, and artists, especially the Romantic artists that admired his passionate eccentricity, brought it into a new light. However, it is generally considered that his unique artistic language, with its focus on expression was only fully understood in the 20th century, when the artistic panorama of the time developed a deeper appreciation for his art.

Fascinated by his imagination, sense of personal visual style, and overall composition, El Greco's work established a foundation for the development of Cubism, a movement in which artists began to abandon a single viewpoint perspective to play with geometric shapes and interlocking planes. He exerted a major influence on Pablo Picasso, who studied some of his works intensively and saw in El Greco's language a 'modern' approach to art. Picasso's painting entitled Portrait of a Painter, after El Greco (1950) can be interpreted as a tribute to the early master.

In a broad way, El Greco can be further seen as a precursor to the canon of modern art, leading the path away from traditional naturalistic approaches into a new artistic dialogue which emphasized culling from emotion, inner drama, and bold new renditions of color and free flowing figuration. His work laid a significant groundwork for the development of Expressionism and the Blaue Reiter Group. We can see a direct link to El Greco in many Expressionist landscapes that utilized a more organic approach to color and form like in the works of Vincent van Gogh.

Christiansen has written that above all, El Greco "was both the quintessential Spaniard and a proto-modern - a painter of the spirit," who rejected a materialist culture and chased the "inner mystical" constructions of life. He emphasizes, that, aside from El Greco's immense influences on various art movements and artists, it remains the spiritual and mystical attributes of his work that establishes his universal legacy.

Influences and Connections

-

![Titian]() Titian

Titian -

![Tintoretto]() Tintoretto

Tintoretto -

![Paolo Veronese]() Paolo Veronese

Paolo Veronese - Jacopo Bassano

-

![Classical Art]() Classical Art

Classical Art -

![Mannerism]() Mannerism

Mannerism - Venetian Renaissance

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI