Summary of Manuel Felguérez

Felguérez is one of Mexico's principal post World War II artists. As the first of his country's artist to broach the formal possibilities of geometric and gestural abstraction, he stood at the forefront of Mexico's move into its "post-muralist" era and he helped align Mexican art with the international avant-garde. His paintings, sculptures, assemblages, and public works represented the artist's total commitment to exploring the aesthetic and material values of the artwork. Felguérez was also the first of his generation to embrace the dawning of the computer age through the production of a number of pioneering digital artworks. His willingness to embrace the overlaps between art and science also led to distinguished teaching positions in Mexico and the US.

Accomplishments

- Felguérez became a torchbearer for the revalidation of post-war Mexican art. He was a leading player in the formation of the Generación de la Ruptura (the "Rupture Generation"). The group collectively affected a "rupture" in the Mexican art and culture by rising up against the socio-political and nationalistic tendencies of works made famous by iconic Mexican Muralists such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco.

- In addition to the influences of Cubism and Constructivism, Felguérez looked towards contemporary European and American avant-gardes, especially Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel, to formulate his "multiple space" painting and sculpture style. These paintings and reliefs used combinations of basic geometric forms and more expressive and gestural elements. He called this process "creating chaos and order".

- During the mid 1970s, Felguérez was at the center of a cutting-edge arts and science research program. In collaboration with the Harvard mathematician Mayer Sasson, Felguérez conceived of the idea the "aesthetic machine" (La máquina estética). Although his work in this field was relatively short lived, his efforts to explore the aesthetic possibilities for new digital technologies gained widespread recognition across the artistic and academic worlds.

- Felguérez's self-analysis was manifested in the art he produced. He was engaged with ontological questions, and his search for this "essence" in his art was reflected in his eagerness to experiment with the tensions between images and materials. In his ongoing push to achieve the ultimate aesthetic freedoms, Felguérez vowed to "never repeat myself".

The Life of Manuel Felguérez

The art critic Jorge Alberto Manrique wrote, "An obsession with finding a kind of philosopher's stone of art is, it seems, what structures all of the varied and even contradictory work of Manuel Felguérez".

Important Art by Manuel Felguérez

Mural de Hierro (Iron Mural)

In 1961, Felguérez took on a project to create a mural for the inauguration of the Diana Cinema. The enormous mural, 28.5 x 3.85 meters, is an important example of the sculpted mural work for which the artist would become well known. The mural is an assemblage of various metal pieces of industrial waste and motor parts. The pieces, all of a rust-brown hue, are arranged in a line that covered close to 30 meters of an ochre wall in a style that was influenced by Constructivist collage. It represents a reinvention of Mexican Muralism in the way that it drifts away from the mimetic and narrative characteristics of the murals that had been produced by artists like Diego Rivera.

Mural de Hierro proved a very controversial piece. Other Felguérez murals made before the 1960s incorporated found materials such as scrap metals, stones, and sand. However, the press deemed this work to be an act of provocation since it did not honor the Mexican Revolution or the ordinary people of Mexico. The mural marked a decisive break with the official discourse on muralism, tied as it had been to the concepts of nationalism, education, and realism that had dominated the "official" Mexican art scene since 1920. Regarding the controversy Felguérez stated "[The Iron Mural] sparked so much debate, but it also led to the recognition of a new plastic language". It is interesting to note that the mural was left abandoned and without maintenance until 2014 when the University Museum of Contemporary Art set about restoring it to its original glory.

Junk metal assemblage - Private Collection

La Máquina del Deseo (The Desire/Love Machine)

La Máquina del Deseo crossed the line of what art was "meant to be" in 1970s Mexico. The work, which broaches the overlap between art and science, is a geometrical assemblage consisting of mobile aluminum pieces and automotive paint held in place by a fixed center structure. The sculpture has a set of metallic panels that feature big circular cutouts that allow us to see the whole structure of the work. A set of rectangular panels in black, red, orange, and white are arranged in two semicircles that contrast with the gray metallic outer panels. Under and above these panels we see lines of three-dimensional cubes in orange and black. We might call the work a "halfway" piece: half-sculpture; half-installation. The title merely reinforces the work's enigma: what kind of machine is this?

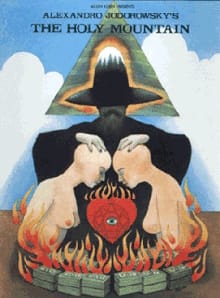

La Máquina del Deseo is possibly the most transgressive piece produced by Felguérez during the 1970s. The original work was designed for the film The Holy Mountain at the behest of the film's Chilean director, Alejandro Jodorowsky who challenged Felguérez to, "see what you come up with because we're going to create an art factory". Felguérez devised a mechanical device through which the actors could engage in acts of love and desire. As Elizabeth Mistry writes, "The film - partly bankrolled by John Lennon and Yoko Ono - gained cult status and notoriety in equal measure for its depiction and what could only be described, even before the #MeToo era, as the exploitation of women. At one point, a naked woman is seen to arouse and be aroused by [Felguérez's] installation". The original sculpture, and its model, were lost after filming, but a reproduction of the piece was made in 2017 under the artist's supervision.

Aluminum and Automotive Paint - Collection Manuel Felguérez and Páramo Contemporary Art Gallery, Guadalajara, Mexico

Tension hacia tres (Tension towards three)

In Tensión hacia tres Felguérez sought to experiment with the possibilities of combining the analytical capabilities of computers with the creativity of the artist. It would form part of a bigger project called The Multiple Space. This abstract painting features a set of geometric shapes with alternating colors. The composition is structured yet dynamic. A pair of black triangles, a mauve, and two ochre, parallelograms are positioned diagonally on the bottom right side of the painting. It is this diagonal placing of shapes that gives the composition its sense of dynamism. Contrasting with this, three white ovals are set at the center of the piece, providing a place on which the viewer's gaze can come to rest. The ovals (to which the artwork's title refers) create a sense of tension while also giving structure to the composition. From between the ovals two red lines emerge and drop following the dynamic diagonals of one of the ochre parallelograms, and, behind all of this, a large gray area, that feels like a background, can be seen in the top left side of the piece.

Art historian Cuauhtémoc Medina saw the work as part of a body of work (The Multiple Space) organized around a "visual alphabet" through which "Felguérez could propose a 'combinatory syntax' that would generate designs supposedly continuous with his own pictorial style". But Felguérez refuted the idea, put to him by the art critic Robert A. Parker, that the computer might have overruled his own creativity. He said, "I tried to relate to the computer from the standpoint of what was already my style. An artist's style is as distinctive as his fingerprints. I sought to identify the features that defined my style I didn't care whether that style was good or bad; what mattered was that, after 25 years making art, my work possessed a language ruled by a syntax that only I used. And it seemed to me that if I was able to input into the computer the combination of elements that make up my style, and kept the work of the machine strictly within those boundaries, then the computer would be unable to invent anything new, or go beyond".

Acrylic lacquer on silk - Tamayo Museum, Mexico City

Jardín del Recuerdo (Garden of Memory)

Jardín del Recuerdo is another example of Felguérez's abstract work. Here, however, we see a more gestural element. The work features a dark textured background rendered in a combination of ochres, blues, grays, reds, oranges, and black. Through this combination Felguérez has created a tactile, three-dimensional, effect. In the center, a set of gestural and curved lines in black creates an amorphic figure/shape that provides a central point on which the viewer's gaze can focus. The spaces created by the curved lines are filled with some gray and ochre, but mostly the artist chooses bright white and red to fill in the central organic figure. These color choices contrast with the background making this central figure/shape even more pronounced.

This artwork, completed in 1987 (more than a decade after he abandoned his interest in digital art projects) is a testimony to the evolving and diverse abstract language of the artist. Even though it still incorporates basic geometrical forms (a staple of Felguérez's art) this piece has a much more intuitive slant. The piece also features a more organic use of shapes, which alludes to the title of the work (The Garden of Memory). Exactly which kind of garden, or what kind of memory, Felguérez refers to remains unknown, however. The free movements are strongly reminiscent of Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel, which the artist acknowledged as influences on his art.

Oil on canvas - Tamayo Museum, Mexico City

Puerta al tiempo (Door to time)

A fine example of Felguérez's approach to public art, the sculpture Puerta al Tiempo sits in the lobby of the General Rectory headquarters at the Metropolitan Autonomous University. The piece weighs some 26 tons and is made of carbon steel. The sculpture was expressively planed by the artist for this space and hangs from a set of supporting girders and features a set of black rectangular metal pieces that merge to form an abstract geometric shape. The choice in material and color renders the sculpture both visually and physically "heavy". The different metal pieces are set in sharp diagonals, which give the sculpture a dynamism that contrasts with its weight.

The sculpture's positioning maximizes its visual impact. It is hung atop the lobby entrance making it look as if it is almost floating on air. This seems like a wholly counter-intuitive placing given that it is such an excessively heavy piece of sculpture. Indeed, the artist stated that its position presented him with the greatest challenge and that he developed a set of solutions through the use of strategically positioned girders. The artwork demonstrates thus Felguérez's willingness to test the limits and uses of raw materials and for creating innovative solutions when creating three-dimensional pieces. The combination of these characteristics create an artwork that simply cannot be ignored. The University, which had commission an earlier sculpture by Felguérez (in 1978), housed an art gallery dedicated solely to his art.

Carbon Steel - Metropolitan Autonomous University, Mexico City

Agenda 2030

In 2018 Felguérez was commissioned to create a painting for the United Nations headquarters. The piece, which measures approximately two-by-five meters, is perhaps the very epitome of the abstract language he developed throughout his long career. The composition is organized around a set of rectangular shapes to which swaths of paint are superimposed. The background has two main rectangular shapes in white and ochre. A set of gestural curved lines in black, and splashes of golden paint, are placed on top of the trick rectangular outlines of the background. The ribbons of paint provide the composition with a dynamism that contrasts with the static background.

Agenda 2030 is displayed in the hall of flags that lead to the General Assembly Hall of the United Nations headquarters - possibly the most important international building in the world - and was commissioned following a series of negotiations with Mexican ambassadors. The commission asked for a painting that would represent the values of international cooperation set by the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 agenda and which would represent the UN's universal and international character. The artist himself stated that "The mural doesn't' have an ideology in its imagery that undermines the universal, it's abstract". At the unveiling ceremony of the painting, the UN Secretary-General stated, "I believe that nothing could fit better here than this magnificent work that will unite us all in the goal of making a fairer globalization, a better world for all, and a safe planet". This highly prestigious commission marks one of the greatest honors in the artist's career; a fitting swansong to such a long and distinguished career.

Oil on acrylic on canvas - United Nations headquarters, New York

Biography of Manuel Felguérez

Childhood

Manuel Felguérez Barra was born in December 1928, in Zacatecas, North-Central Mexico. The area is known for its rich deposits of silver and other minerals, its colonial architecture, and the important role it played during the Mexican revolution. However, at this time Zacatecas was in the midst of the Cristero uprising, a rebellion that was originally religious but quickly turned into a battle for land ownership. Felguérez's family was forced to flee as the workers of the hacienda (large estate and plantation) that Felguérez's father owned, took control of his land by force. In the 1930s, the hacienda was expropriated under President Lazaro Cárdenas, taking away most of the family's holdings. In 1934 the family decided to abandon any interest in the hacienda and relocated to Mexico City where his father tried to petition the federal government for compensation for the loss of the family's property.

Sadly, Felguérez's father died in 1935, and he grew up under the guardianship of his mother and his maternal grandparents. The boy's grandparents owned a cinema which his mother managed and, as the arts journalist Elizabeth Mistry writes, "The time he spent there sparked a lifelong interest in the moving image, which was to come to a head many years later when he collaborated with the director Alejandro Jorodowsky on the 1973 counterculture sci-fi epic, The Holy Mountain". Felguérez liked to box and was a keen supporter of Lucha libre (professional wrestling) at the Arena Mexico (even earning money by supplying live bats as between-bouts props). It was also in Mexico City where the artist first tried marijuana and campaigned for its legalization throughout his life. Felguérez received his primary, secondary and high school education through the Marxists school Colegio México and was also a Boy Scout from age eight. It was in the Scouts that he met his best friend Jorge Ibargüengoitia, who would later become an important Mexican writer. Through their membership with the Scouts, and its international exchange program, Felguérez and Ibargüengoitia took the chance to tour Europe in 1947.

Early Training and Work

Once in Europe, the two friends took the chance to visit many museums and cultural sites, including the Louvre Museum and Notre Dame in Paris, The Vatican Museum in Vatican City, and the British Museum in London. The two friends traveled mainly by hitchhiking and staying at the houses of Scouting contacts. Felguérez was deeply impressed with European art, especially by the English Romantic painter, J.M.W. Turner. According to an anecdote shared by Felguérez and Ibargüengoitia, the pair were in London traveling by boat on the Thames River when the artist made a sketch of his surroundings, signed it, and presented it to his friend stating, "See, now I am an artist!". Ibargüengoitia said later that, although he laughed at the time, he felt that this was the very moment when Felguérez's artistic career began.

Upon their return to Mexico in 1948, Felguérez enrolled in the arts Academy of San Carlos, despite his family's wishes for him to become a doctor. However, he only studied in San Carlos for four months, having become frustrated by its focus on muralism and its worship of the Mexican School of Painting. Felguérez took the decision to return to Europe to continue his art education. He enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, where he took courses with French-Russian Cubist, Ossip Zadkine. The experience would provide the foundations for his love of abstract art, something quite alien to Mexican artists at the time.

Returning to Mexico in 1950, Felguérez undertook a bachelor's degree in anthropology and history. This led him to take classes in modern art and crafts with the Costa Rican-Mexican artist, Francisco Zúñiga. The following year he met his first wife, and future mother of his two children, Ruth Rohde. During this time the couple moved to Puerto Escondido where the artist made a living selling handicrafts. Indeed, the dominance of the state-funded Mexican Muralism movement made it very difficult for Felguérez to make a living as an artist and he was limited to exhibiting his art in small, independent galleries. It was during in this period that Felguérez started producing his assemblages - or what are now often referred to as his "sculpted murals" - for which he used materials such as shells, scrap metals, stones, and sand to create abstract works.

In 1954 Felguérez held his first exhibition at the French Institute of Latin America. It proved a great success, with the artist selling the entire collection. This exhibition also earned him a scholarship to study at the Académie Colarossi in Paris. He relocated to France (with his small family) residing in a large apartment in the Maison du Mexique complex (a post-graduate student's residence located at the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris). While in Paris, Felguérez met the artist Lilia Carrillo who was studying in the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Their professional relationship, which saw them visit Georges Braque's studio, and exhibit together at the Petit Palais museum, led to a romance.

In 1958, Felguérez had his first individual exhibition in 1958 at the Antonio Souza Gallery in Mexico City. The journalist and historian Socorro Garcia records that Souza's tenure as the owner of the gallery reflected his interest in promoting art that did "not follow the line of 'the Mexican school'", and which found its "form of expression in abstraction". (Among the other artists to exhibit at Souza's gallery were, Gunther Gerzso, Juan Soriano, José Luis Cuevas, Wolfgang Paalen, Lilia Carrillo, Felipe Orlando, Maka, Roger Von Gunten and Pedro Coronel.)

Mature Period

Felguérez divorced Rohde in 1959 and married Carrillo the following year on a trip to Washington D. C.. Back in Mexico, the newlyweds became part of a group of artists who became known as "La Generación de la Ruptura" (the "Rupture Generation"). The term "La Ruptura" was coined by the poet and Nobel laureate, Octavio Pax, who used it to describe a new generation of Mexican artists and writers who rejected the nationalistic values of the Mexican School of Painting and the Mexican Muralism movement in favor of complete aesthetic freedoms. Many artists identified with the new movement, including Cuevas, Coronel, Francisco Toledo, Leonora Carrington, and Vicente Rojo. La Generación de la Ruptura was not, then, defined by a homogenous style, but rather a shared interest in exploring the stylistic traits of current international (non-Mexican) art trends. In Felguérez's case, this included Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel.

During this period, Felguérez produced paintings, and the first of his signature sculpted murals, for private and public buildings. He completed two of his most important murals at this time: the Iron Mural (1961), at the Diana Cinema, and Song to the Ocean (1963), at Deportivo Bahía. The murals revised the Mexican tradition (of muralism) by employing a more abstract and experimental approach. Felguérez had shown a way of approaching muralism outside the strict narrative and nationalist ideals it was linked with historically.

His openness to foreign influences allowed Felguérez to develop a more universal style and to foster a dialogue between Mexican art and international movements. The artist later stated, "Our generation abandoned nationalism, and this led us to the other extreme, to internationalism and universalism". However, his art failed to win over the Mexican art establishment which remained stubbornly committed to the values of the Muralists. That being so, Felguérez had to complement his income with teaching jobs. He took up posts at the arts faculty at the Ibero-American University, and the National School of Plastic Arts at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Then, in 1966, he accepted the overseas role of visiting professor at Cornell University (in the US).

Felguérez was also involved in the formation of Salón Independiente exhibitions which ran between 1968-71. Historian Daniel Quiles explains, the first Salón "was a response to 'Exposición Solar 68' the official showcase of contemporary Mexican art sponsored by the 1968 Olympics [...] Objecting to that exposition's nationalism, rigid formal categories, and emphasis on prizes, the forty-five artists who presented in the first Salón stressed 'free expression,' without political or commercial motives, as well as international representation". Quiles adds that "the 1968 edition had been put together with relative haste and was barely documented; only a handful of the exhibited works could be recovered [...] By the next year, however, the organizing artists - among them Arnaldo Coen, José Luis Cuevas, Helen Escobedo, Manuel Felguérez, Francisco Icaza, Myra Landau, Felipe Orlando, Ricardo Regazzoni, Rojo, and Kazuya Sakai - had given the event an austere revolutionary identity. They set up a governing board, raised funds, and forbade members to join other salons or show in biennials premised on competition or nationalism".

Late Period

As a result of his work at the Ibero-American University and UNAM, Felguérez ventured into experiments with Digital art. At the time there were just three computers in Mexico, one at the Mexican Institute of Social Security, and two at the UNAM. Through his work at UNAM, the artist experimented further with geometric forms (by now a motif in his art) using computers. The project, according to Art Historian Cuauhtémoc Medina, "was mostly a rehearsal for systematic production, based on strictly postulating a visual combinatory language". In 1973, as a direct result of his experimentation process, the artist published the book The Multiple Space outlining his creative processes and how these dovetailed with digital technology.

As curator Esteban King explains, "at the beginning of the seventies, he began a series of investigations focused on exploring a system based on the combination of certain basic elements (such as the triangle, the square, the circle and their derivations) to build, according to his own words, a 'plastic alphabet'. To achieve this, he thoroughly analyzed the production he had made throughout the previous decade and synthesized the elements that made it up; in his own words, he 'geometrized' his time in Art Informel, with which he discovered the components that structured his own creative practice. In this way, he developed a kind of language, with its own operating rules, which he included under the name 'The multiple space'".

In 1973 he also produced a sculpture/prop for Jorodowsky's controversial quasi-religious/science-fiction movie, The Holy Mountain. Also in 1973, Felguérez was formally acknowledged within his own country's arts establishment when he was inducted into Mexico's Academia de las Artes. In 1974, five years after suffering an aneurysm which left her paralyzed, his wife (Lilia Carrillo) died. He married Mercedes Oteyza (the ex-wife of Mexican novelist, Juan García Ponce) in the same year (they remained married until his death).

In 1975, and on the back of the publication of The Multiple Space, Felguérez was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to work with the Colombian engineer Mayer Sasson at the Harvard Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis at Harvard University. Felguérez stated in an interview, "When you teach art, you encounter two different knowledge fields: one that is rational and one that is irrational. The latter cannot be taught, because it depends on sensibility. But rational knowledge can be taught, and in doing so I was surprised to see that I was using the resources of logic and mathematics. My style was conceived in mathematical terms, and this made me wonder whether computers could be of help. But I wasn't sure about they could do, so I decided to use them in an intuitive way. Nevertheless, before I actually set to do it I went through three years of analysis and three more years before I started working with Mayer".

Felguérez and Mayer explored the limits of a computer's capacity to analyze and systematize combined with the creative faculties of an artist. They named the venture, Difference and Continuity. Felguérez soon learned to use the technology to create art his first computer art project, The Aesthetic Machine. By using a process of codification, selection, or contradiction based on the original model of his mathematical drawings, he was able to multiply and reproduce selected designs; what he called "forms-ideas". The upshot was a set of sculptures and paintings that established him as the pioneering figure in the development of digital art in Mexico.

Historian Abby McEwen explains that in 1976, Felguérez left computed design behind him and, in his words, "went back to turpentine. [...] I began working with a game of chance [playing] intellectually with the idea of chaos and order. In place of the chaos created by the computer, I was trying to figure out how I could create chaos on a canvas. The easiest way to do it was to splatter the paint and let gravity decide the forms". McEwen explains how Felguérez "evolved his technique over the years, incorporating the squirt gun, dripping paint from the can, and moving the canvas itself".

Felguérez continued to produce art into his eighties, experimenting and traveling for exhibitions. His late works mainly focused on abstraction often containing basic geometric shapes such as circles, triangles, rectangles, and squares. He described his art as being in constant experimentation and he believed it was this evolution that distinguished an artist from an artisan. In 1987 he was named an "illustrious citizen" by the state of Zacatecas and in 1988 received Mexico's prestigious National Arts Award.

In 1998 the City of Zacatecas opened the Manuel Felguérez Abstract Art Museum featuring about 100 of his works, along with another 110 works by Mexican and international artists working in an abstract style. Felguérez donated many of the artworks from his own collection under the condition that the museum would be dedicated to the abstract art of his and future generation/s. In 2018 he received a commission to make a large-scale painting to be placed at the hall of flags that lead to the General Assembly Hall of the United Nations headquarters. It was a fitting finale for the artist who died in 2020 from COVID-19, at the age of 91.

The Legacy of Manuel Felguérez

Felguérez was the leading figure in the development of abstract art in Mexico, and as such, he was as an inspiration to post-war Mexican artists. Indeed, as one of the founders of the La Generación de la Ruptura (the Rupture Generation), he helped widen the nationalist discourse set by the Mexican School of Painting. He brought about a renewal of Mexican art - through what the British-Mexican artist Brian Nissen called a "remarkable pictorial intelligence" - by suggesting new artistic possibilities at a time when figurative muralism was the all-conquering national art.

In underlining the "vitality and relevance" of his works, curator Pilar García pointed to Felguérez's "expertise in working with large format pieces, through a multidisciplinary and collaborative logic". His penchant for experimentation, moreover, made him one of the first to recognize "the possibilities that exist in the relationship between science and art by ascribing a creative quality to the [digital] machine". It was, for Garcia, this "conjunction - always present in his work - between the pictorial and the sculptural [that] proposes different visual solutions to a specific form" that helped deliver Mexico onto the international stage of late twentieth century avant-gardism.

Influences and Connections

![Ossip Zadkine]() Ossip Zadkine

Ossip Zadkine- Jorge Ibargüengoitia

- Lilia Carrillo

- Francisco Zúñiga

-

![Cubism]() Cubism

Cubism -

![Constructivism]() Constructivism

Constructivism -

![Abstract Expressionism]() Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism - Informalism

- Alejandro Jorodowsky

- Vicente Rojo

![Ossip Zadkine]() Ossip Zadkine

Ossip Zadkine- Jorge Ibargüengoitia

- Lilia Carrillo

- Francisco Zúñiga

-

![Digital Art]() Digital Art

Digital Art - Rupture Generation

- Abstraction

Useful Resources on Manuel Felguérez

- Manuel Felguérez: Trajectorias/TrajectoriesOur PickBy Pilar García, Manuel Felguérez

- Manuel Felguérez. El future era Nuestro (In Spanish)By Pilar García, Manuel Felguérez, Cuauhtémoc Medina, Angel Miquel, Daniel Montero

- Manuel Felguérez. Obra púbica/Public WorksBy Jaime Villarreal

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI