Summary of Morris Graves

Graves was the first modern painter of the Pacific Northwest to gain national and international recognition. Gaining early notoriety for a series of spectacular Dadaist pranks, he is best known as an introspective and intensely spiritual artist who brought the influence of East Asian aesthetics and philosophy to bear typically through images of birds, flowers, chalices, and other symbols of Eastern spirituality. A one-time friend and enemy to Mark Tobey, he was (like Tobey) a member of the so-called Northwest School, and was celebrated by many of his followers as a modern day mystic who came to view art as an act of pure communion between man and the natural world.

Accomplishments

- In an era when Abstract Expressionism was seen as the way to express the pure unconscious, Graves "inner eye" gave rise rather to a figurative style known as "symbolic consciousness". Paying homage to Eastern values, he turned to symbols of the natural world as a means of seeking absolute truth (or redemption) through art. Given the supremacy of the New York School, his painting stood out as the most original American art of its time.

- Deeply troubled by the "noise" of the modern industrial world, Graves pursued a life of "purposeful isolation". By devoting his paintings and drawings to the sights and sounds of the natural world, his aim was to tap into the part of the collective American psyche that draws the individual back to the beauty of their unspoiled environment.

- Known for his paintings and drawings, and to a lesser extent his Dadaist performances, it is often overlooked that Graves devoted an enormous amount of creative energy to building aesthetic living environments that would provide the ideal conditions for him to realise his artistic vision. His self-built homes - "The Rock", "Careladen", "Woodtown Manor", and "The Lake" - were, according to his biographer, Deloris Tarzan Ament, his "unsung works of art" and stood out as unique artistic havens of "exemplary beauty and serenity".

- By turning in his late career to the theme of wildflowers, Graves had come full circle from a childhood preoccupation. Graves produced minimalist paintings often featuring singular flowers in jars. Painted on un-primed surfaces using dark earth tones, with small bursts of light colors, Graves introduced the Zen ideal of beauty as an absolute concept to the register of modern American art.

The Life of Morris Graves

A deeply spiritual man Graves declared "I paint to evolve a changing language of symbols"; that is, to develop a language by "which to remark upon the qualities of our own mysterious capacities which direct us toward ultimate reality".

Important Art by Morris Graves

Moor Swan

Speaking of Graves's work, curator Nancy Wilson Ross suggested that "religiously motivated painting depends for its communicability on its use of symbols [and in] order to be generally intelligible it must submit to the demands of a prescribed iconography, a language of symbolic representation in which observer shares with artist the ideas impelling its creation". At the same time, the symbol of the bird has spoken throughout history of the artists' own state of mind. As the art critic Gerald Heard added, "in all significant painting from Catal Hüyük to Hieronymus Bosch the Bird has stood for that drive or force which bears the migrant soul of man into another state".

With its sinuous neck and arched back rendered in Chinese-style brushwork, Graves's lone Moor Swan is almost camouflaged by the earthy colours of its desolate surroundings. In nature, the moor swan is isolated from its white counterparts, its colour associating it with darkness and death. Yet the black swan also carries connotations of a most divine creature, even though it does not conform to the expectations of nature. Read this way, one can perhaps see why Graves chose it as his subject: a creature, like him - a deific outcast. Indeed, Graves alluded this assessment when he stated that "Seeing divine creations [...] seem sufficient reasons to use painting as my voice". Interpreting Moor Swan as a symbolic self-portrait, the Seattle art critic Deloris Tarzan Ament added that "One glance and you know that the swan feels misunderstood; that he holds secrets".

Moor Swan brought Graves's his first taste of recognition. Having submitted the painting to the 1933 annual exhibition of Northwest artists held at the Seattle Art Museum, it won him the $100 first prize.

Oil on canvas - Seattle Art Museum

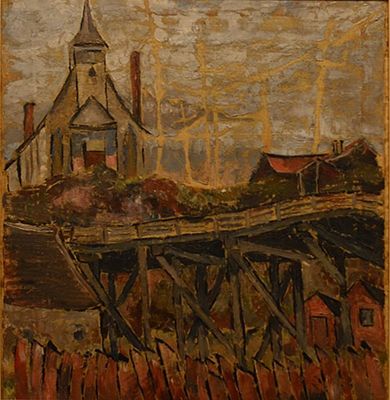

Church at Index

In Graves's bold graphic painting, we see the artist's appreciation of the work of Cezanne, Van Gogh and Japanese prints in the strong outlines and fragmentation of form. There is also a resemblance here to Mondrian's early deconstruction of churches and trees. One of Graves's early supporters, Elizabeth Bayley Willis, stated that "Graves had developed his style from the minute examination of moss, and the study of scaly surfaces of old barns, and used loose painting with a palette knife on coarse absorbent canvas hoping to attain the quality of antiquity of old frescos". It is, however, the transparent dusky light of the Northwest that is the recurring feature in Graves's early paintings. Ament cited Malcolm Roberts, a Surrealist painter of the period, who referred to "this daily magical interval [as] the 'Hour of Pearl'", or what painters on the French Riviera knew as the "'l'heure bleue'".

Ament described the effect thus: "This long leave-taking of light is a time of transformation. Such light is visible in Graves's early paintings, which seem to be set neither at night nor in daylight, but in some charged intermediate illumination. They carry a sense of consciousness transforming and refining itself to more idealized levels. Faint perfect forms echo crisp imperfect ones; gray shapes spill into color. They are permeated with longing".

Oil on canvas - Seattle Art Museum

Dove of the Inner Eye

At the top center of this painting, a dove - the enduring emblem of peace - is drawn to a ray of light despite being tightly ensconced in a rocky crevice making it an object of prey for an approaching snake. Webs of angular white lines, clearly influenced by the calligraphic style of Mark Tobey, shimmer above the color field, trapping the bird much like a fly in a spider's web. Graves's move in the 1930s from oil to watercolour, tempera and ink allowed him to display his intricate draftsmanship and offered a range of media for greater refinement and delicacy. Given the time it was produced, the image would seem to reflect the artist's heightened anxiety about being drafted into the military (during the Second World War). Yet the painting also carries a timeless mythic and allegorical resonance.

At his Fidalgo Island residence (which he called "The Rock") Graves lived alone with his beloved Swiss dachshund, Edith (named in honor of the poet Edith Sitwell). There he meditated, painted, and listened intensely to night sounds, drawing the wildlife that made those sounds from his imagination. He also tried to paint sound under the Vedic religious concept that sound and form merge into one and the same thing. When the weather conditions allowed, Graves walked out under darkness before returning to The Rock where he painted until sunrise. It was under these conditions that he produced his famous Inner Eye series which symbolised Graves's own spiritual quest for self-realization. "The birds became characters in a hallucinatory drama created by the body language of their eyes, feathers, posture, and the white light that falls on them and gathers around their feet," wrote Kay Larson, art critic for New York magazine.

Opaque watercolor on oiled paper - Seattle Art Museum

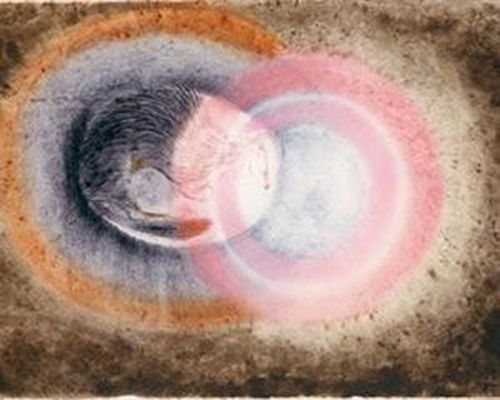

Hibernation

Graves's Hibernation series signify something of crossover point in his career. Having left America for Ireland, the series saw him distil all traces of his personal anxieties (about industrialization and war); focusing solely on a deep and pure meditative quality that tapped into the artist's lifelong preoccupation with nature and Eastern philosophy. The painting itself depicts a mink, curled in a foetal position, hibernating peacefully in the core of the earth. The animal appears to be encased in a luminous egg from which emanates a cosmic pulse that is rendered by Graves in pink, and warm, earthy tones. Graves's "floating" creatures confirm the artist's fascination with the transcendental aspect to be found in natural phenomenon. Indeed, according to the art critic Gino Pennacchietti, "Graves sought to paint with such timelessness and worldlessness [as] to escape the affairs of man, the distortions of the natural world, and seclude himself into the frightening, yet humbling and sublime world of the earth".

Pennacchietti discussed the Hibernation series as offering a "fundamental break with artistic modernism" which did not meet with the approval of the "number one modernist taste-maker", Clement Greenberg. The famous critic spoke of Graves's "irreverent subject matter" which was so "narrow and [...] far removed from the mainstream" it was left with "nowhere to go". Greenberg wrote, "Graves is subtle [and] had to be within the narrow limits set for himself". He added that "Something very spontaneous, very valid, moves at the bottom of his art, but for the present it does not materialize as anything much more than an impulse, an initial impulse". It was not lost on Pennacchietti, however, that by the 1950s Graves and the other Northwest school artists would "influence a whole generation of Abstract Expressionist painters, including some of Greenberg's choice favourites like Pollock".

Watercolour on paper - Smithsonian American Art Museum

Instruments for a New Navigation

Circles of glass or pale stone are balanced on slender rods above solid stone pedestals. Many of them are perforated with a central lens, suggesting an instrument to be looked through. They are totem-like, ritualistic and ceremonial. In a significant shift in scale and departure from his paintings, Graves developed this series of sculptures during his stay in Ireland. In the era of space travel and space exploration, it offered his personal meditation inspired by his observations of the night sky and the burgeoning American/Russian space race. The pieces were, he said, "designed to feel their way into a new aspect of the three-dimensional phenomenal universe [...] in search of the human spirit as it implores itself to gain insight into the mystery of consciousness".

In 1964, the works came to the attention of NASA scientists and engineers, who invited him to include his art on the early lunar exploratory missions. Graves came up with a 12-inch gold rod tipped with an amethyst to be installed on the Orbiting Astronomical Observatory, but the project was dropped when it was feared that the amethyst would disintegrate and pose a threat to the Observatory. A disillusioned Graves dismantled the works and did not display them until the final year of his life.

Cast bronze, glass, and stone

Summer Flowers for Denise

Late in life, the near-reclusive Graves turned his attention to wildflower painting. In this example, a spray of purple flowers are arranged at a respectful distance from a burst of white flowers in a rack of glass bottles, reminiscent of the paintings of Giorgio Morandi. The background is geometric, formal and mysterious, the whole composition Japanese in design. Against chalky, fading surfaces, reminiscent of aged fresco, Graves would set small, intimate objects: a bottle or two of wildflowers and perhaps a bowl of plums, so placed as to suggest that each is an individual treasure. As still lifes, they were "profoundly still". The subjects seem to be in fact not flowers (or fruit) so much as light. They are painted with such delicacy that the pigment seems almost breathed into place. Graves projected intensity into them by rendering the images veiled and shimmering, suggesting not only the fleeting life of blossoms, but the evanescence of life itself.

Oriental in their sensibility, Graves's flower paintings are reminiscent of, and significantly distinct from, his early symbolic and metaphoric works. What unites them is the artist's lifelong quest to transform the spiritual into the pictorial. "We must so live," Graves wrote, "that we can sensitively search the phenomena of nature from the lichen to the day-moon, from the mist to the mountain, even from molecule to the cosmos - and we must dream deeply down into the kelp beds and not let one fleck of the significance of beauty pass unapprised and unquestioned and unanswered". The best of Graves's late flower paintings, wrote Ray Kass, "possess a delicacy of light and proportion that commands the attention of their audience and inspires a meditative calm".

Tempera on paper - Seattle Art Museum

Biography of Morris Graves

Early Years and Training

Following a failed attempt to establish a homestead farm in Fox Valley, Oregon, the bankrupted Graves family returned with their new-born son to Washington state where they resettled in Edmonds, a city 15 miles north of Seattle. Graves's biographer, Deloris Tarzan Ament writes that during her sixth pregnancy, Graves mother, "had prepared a pink layette, certain that after five sons, this would be a daughter". She was, nevertheless, enamoured with her youngest son stating: "He was a beautiful baby - big brown eyes and dark hair, with a little faraway look in his eye - and very friendly. We named him after Morris Cole, our favorite minister".

Graves was a sickly child, given to mood swings, and long spells of introspection but he developed a passion for the natural world during long periods of recuperation from bouts of pneumonia. He passed the days in the family garden watching birds and mentally designing gardens for them to live in. By the age of 10, Graves could identify some 40 varieties of wildflowers and he started entering wildflower bouquets into county fair competitions, and arranging flowers for his family's Methodist church. His mother remembers that, aged just 11, he presented an eight-foot-high Easter cross covered with flowering cherry blossoms to the church. It was around this time that Graves first daydreamed of becoming an artist. He spoke of seeing a collection of allegorical murals in Century magazine and, although he couldn't remember the name of the artist, the images stayed with him: "There was something about the volume of those forms on a two-dimensional plane that impressed me greatly" he recalled.

Lacking in aptitude for formal education, Graves dropped out of high school in his sophomore year and, in 1928, he and his brother, Russell, joined an American Mail Line ship as cadets. The ship sailed to Manila, Japan, China, Hawaii, and San Francisco. During shore leave in Japan he explored the countryside on the outskirts of Tokyo, explaining later that the Japanese had "the right way to do everything. It was the acceptance of nature - not the resistance to it. I had no sense that I was to be a painter, but I breathed a different air". The influence of East Asian culture would have a life-long impact on his art.

In 1930, after stowing away on a coastal steamer bound for New Orleans, Graves stopped to visit his maternal aunt and uncle in Beaumont, Texas. Although he was already 20 years old, they persuaded him to stay long enough to finish his high school education. His eccentric behaviour, including walking barefoot to and from school, was a source of curiosity for the other students and his more accommodating art teachers. One of them, Bernice Burrough, later recalled that "he was so fascinating that some students followed him around to observe his interesting antics". Graves served as art editor for the school annual, Pine Burr, decorating it with art deco and Japoniste style bird motifs, before finally graduating as a 22 year-old. He spent the summer in New Orleans where he gained his first experience as a payed artist having been commissioned to paint decorative screens for a New Orleans business owner.

Mature Period

On his return to Seattle, Graves met and grew close to the painter Guy Anderson, a man with whom he haunted bookshops, travelled to the mountains and painted. They would share the same studio and an affinity for all things Oriental. Anderson was critical Graves's early flower and bird paintings, calling them "too decorative", and encouraged his friend to treat his subjects more symbolically. Anderson was happy to concede, however, that his partner "had remarkable taste and the experience of extraordinary color at his command".

Graves's painting Moor Swan, referred to by Ament as a "symbolic self-portrait", won him first prize in the Seattle Art Museum's 1933 Northwest Annual Exhibition; the major regional art event of the year and at which he would become a regular exhibitor. His win also led to the patronage and guidance of Dr. Richard Fuller, the museum's founding director. Graves and Anderson, with whom, it is widely thought, he was engaged in an intimate relationship, took a road trip to Los Angeles, along the way painting farm animals in the style of Gauguin and Van Gogh, and closely observing birds and the mineral world. They raided gardens for food, picked and sold strawberries, and camped in their truck or abandoned houses, which they also ransacked for antiques which they sold.

Graves built a small studio on his family's property (in Edmonds), but it burned down in December 1935, destroying many of his works and his cherished collection of Asian art objects. Possibly as compensation for his loss, Fuller offered Graves his first solo exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum. Around this time, he began his lifelong study of Zen Buddhism, attending the Buddhist temple in Seattle: "Zen stresses the meditative," he said, "stilling the surface of the mind and letting the inner surfaces bloom".

Anderson's mother had told Graves about Father Divine, a charismatic Harlem preacher who pronounced himself "God Made Flesh". Father Divine was on a mission (from God) to lead the chosen people out of the economic disaster of the Great Depression and in January 1937, Graves travelled to New York City where he spent five months with Father Divine's International Peace Mission movement. Though the Mission provided him with lodgings, Graves earned pocket-money by washing dishes and cleaning laundry. He took time out to sketch animals at the Bronx Zoo, as well as making a series of flat colourful images of Father Divine's "angels". On his return to the North West he bought 20 acres of land on Fidalgo Island at a tax sale for $40.

Around this time, Graves started to gain notoriety for his unusual behaviour which resonated with the bizarre antics of the Dada movement. For instance, in December 1938, he staged a protest at a John Cage concert in Seattle, arriving in regal style while his friends rolled out a ragged red carpet in front of him, spreading peanuts on the floor and brandishing dolls eyes fixed to opera glasses. In the fourth movement of Cage's quartet, Graves cried out "Jesus is everywhere!", before being escorted from the hall. He carried on the evening dancing alone outside the venue. Cage had been highly amused by the disturbance and became a devoted friend to Graves, even allowing him to move into his living room. The composer described his new friend in fact as "a colourful and pivotal figure among a small and adventurous group of young Seattle artists" while he himself started to participate with Graves in his Dadaist "performances".

Through his involvement with the Works Progress Administration (the WPA was established to employ out-of-work artists in the creation of art for municipal buildings and public spaces) Graves met Mark Tobey, an artist 20 years his senior. Graves (who was painting in brilliant reds and black, in tempera overlaid with beeswax) was impressed with the Seattle-based artist's calligraphic line and his use of tempera on Chinese paper. Graves began to deploy similar motifs of white lines seen through gauzy light in paintings such as Bird Singing in the Moonlight and Shore Birds Submerged in Moonlight. "He has put language in my hand", Graves said of Tobey. But his appropriation of Tobey's signature style, not to mention Graves's imminent commercial success in New York - achieved ahead of his elder - would lead to strained relations between the two. Tobey stated that "Without my ideas he would be nothing" but, as Ament pointed out, "by incorporating 'white writing' into narrative interpretations of nature, Graves used ['white writing'] in more metaphorical ways than did Tobey. In [Graves's] hands, it suggested a quality of consciousness".

Ament added that a frequent companion of Graves and Tobey was Lubin Petric (the then partner of Graves's younger sister, Celia). As Ament says, "Lubin, who was of solid Serbian stock, was himself a gifted painter, but his talent was lost to alcoholism. He regularly painted work in the style of Tobey and Graves - work that easily passed for paintings by those artists, especially since during the 1930s Graves did not usually sign his work". Growing tired of the WPA project, Graves headed for the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico in the fall of 1938. He returned to the US a year-or-so later with a chest full of beautiful rocks, and a collection of paintings he had made of fighting cocks.

In 1940, Graves began building a house on his Fidalgo Island land, naming it "The Rock". The house was, to begin with, little more than a hut but over time Graves extended The Rock through a series of single file rooms, some of which had windows covered with rice paper (to capture the shadows of the wooded surroundings). The premises could only be reached by a trail and Graves had to fetch water from a service station two miles away. His close friend and New York dealer Nancy Ross wrote: "No stranger could have found it undirected, for the road that reached it was little more than wheel tracks through a forest, leading at the end up a discouragingly steep slope to a rounded mossy plateau whose stony slopes pitched down hundreds of feet on all sides [...] One entered the house by way of a Japanese style garden: sand, wind-twisted trees and arrangements of several rocks so enormous one could hardly credit the fact that Graves had brought them up here".

Between 1940 and 1942, Graves worked at the Seattle Art Museum. It was the museum's policy to employ artists on a rotation scheme (two weeks on; two weeks off) to provide them with some income while also allowing them time to create art. During his two weeks off, Graves isolated at "The Rock", becoming fully absorbed in nature and his painting. He lived a nocturnal existence, venturing out under cover of night, and painting until dawn. Many of his "nocturnal" works featured his iconic motif of birds trapped in layers of webbing or barbs. These pieces were symbolic of the artist's heightened anxieties for the survival of mankind and the natural world under the duel threats of modern industry and world warfare.

Graves participated in two group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York: 35 under 35 and Mystery and Sentiment, both in 1940. But it was in 1942 that Graves achieved his major breakthrough. Following a visit to his studio, Marian Willard Johnson and Dorothy Miller (and despite some consternation from the artist himself) decided to promote his art. Willard Johnson gave him a solo show (the first of a total of fourteen over his career) at the Willard Gallery while Miller included him in MoMA's showcase for emerging American artists working outside New York, Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States. It what was an unprecedented endorsement for an upcoming artist, MoMA director Alfred Barr purchased a total of eleven works (at $100 each) for the museum. Ament added that "Not only did all 19 of his paintings in the show sell, but so did an additional 26 pieces not on exhibit, many of them to museum staffers". Art News described Graves as the "sensation of the show [...] His haunting pictures of birds bathed in a sort of ectoplasmic moonlight are something entirely new". The renowned art collector-cum-critic, Duncan Phillips, meanwhile, called Graves an "original genius" and bought several pieces for The Phillips Collection in Washington, DC. In Ament's words, Graves's "15 minutes of fame had arrived".

In 1942 Graves was drafted into the army. He registered as a conscientious objector, but having reported for his physical examination, he was informed that his application, which had been submitted late, had been rejected (evidence emerged later that his involvement with Father Divine had been a factor in his rejected application). He refused to take the oath of allegiance and attempted to flee before being caught by military police and transported to the stockade. On his release Graves escaped the camp and headed for home. His friends, the Japanese-American designer George Nakashima and his wife Miriam, were staying with his mother before being taken to a detention camp. Before the authorities took him away, Graves demonstrated his solidarity with his Japanese friends by hugging both George and Miriam. This innocent gesture led to allegations of being a collaborator and Graves spent the year in a military prison in Camp Roberts in California which he described as a "zone of evil" with a "regimental life and public toilet atmosphere". Graves deeply missed his dog, Edith, whom he left in the care of the Seattle curator and dealer Elizabeth Bayley Willis. He wrote many letters to the dog as well as to Willis. He pined for the Northwest saying he missed "the heavy rain on the roof, and the wonderful blue luminosity over the Sound at dusk".

While imprisoned at Camp Roberts, Graves sank into a deep depression. He became reclusive and refused to communicate with other camp members. In December 1942, a psychiatrist concluded that Graves was ill-equipped for military service and recommended he be returned to civilian life. He finally secured his military release in March 1943 with an "honorable discharge" (which he rejected). He wrote to Willis, "I am coming home home home home home home home home home home HOME. Dear God make me understand the magnitude of that privilege".

Graves's career quickly took up where it had left off. He painted the Morning Star and Journey series and held solo exhibitions at the Arts Club of Chicago, the Detroit Institute of the Arts, and the University Gallery, in Minneapolis, all in 1943. Four of his paintings were included in MoMA's Romantic Painting in America exhibition. Other paintings were exhibited at the Phillips Memorial Gallery, in Washington, D.C. According to Newsweek, Charles Laughton bought seven of his paintings, all of which the actor hung in his bedroom.

Despite his rising star, Graves was depressed, not least about surge in the building of local industry. In a lengthy letter to Willis, he wrote, "Do you think that I could live alone among the dry rocks and starved willows and not detect the thin cloud of waste pollen drifting?". Responding to the relationship between Tobey and Willis, meanwhile, he warned her off: "If you need a lover, do not look to Mark [Tobey]". Tobey would in fact propose marriage to Willis but again Graves protested to the coupling. Ament suggests that although Graves could not spell out the reason why, "it doubtless hinged on his knowledge of Tobey's sexual preference for men - something it would have been ruinous to Tobey's career to divulge at that time in history". She added that Tobey "knew immediately when Willis refused him that Graves was responsible for her change of heart [and that] rather than any quarrel over who claimed credit for white writing, may have lain at the heart of bitter feelings between the artists".

In 1945, Graves made a second application for a Guggenheim Fellowship. He wrote in his application: "The artists of Asia have spiritually-realized form rather than aesthetically invented imitated form. From them I have learned that art and nature are mind's environment, within which we can detect the essence of man's Being and Purpose, and from which we can draw clues to guide our journey from partial consciousness into full consciousness ... I seek to move away from that Western aesthetic which emphasizes personalized expression of forms without a profound content to support them ... to move away from exhibitionism called self-expression; and toward Eastern art's basis of metaphysical perceptions which produce creative painting as a record ... an outflowing ... of religious experience".

Despite public criticism from the likes of Clement Greenberg, who, writing in the British journal Horizon, said the range of Graves's work had "turned out to be so narrow as to cease even being interesting", Graves received the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1947 and headed for Japan. However, his passage was blocked by the US authorities and he was obliged to decamp in Honolulu for five months. In that time he produced some 50 paintings, inspired by ancient Chinese pieces in the collection of the Honolulu Academy of Art, and attended Japanese language classes at the University of Hawaii. Having had his visa to enter Japan rejected (probably because of his besmirched military record) Graves returned, with the Hawaiian-Japanese painter Yoni Arashiro, to Seattle where he used his grant money to construct a house in a forest above Richmond Beach.

Sited in a grove of cedar and maple trees, "Careladen" was one of the first homes in the Northwest to be built of cinder block. Designed with the help of architect Robert Jorgensen, the house was conceived along the lines of a French country house with 14-foot-high ceilings. Sadly (as far as Graves was concerned) Richmond Beach had proved a popular location for developers and the rising noise pollution caused by bulldozers and other industrial machinery would drive Graves away from Careladen. He could no longer hear the sounds of insects and birds chatter, or the movement of trees and expressed his torment through a series of paintings called Machine Age Noise. In a letter to Willard Johnson, he wrote: "The roads that have been smashed through woods in a day - a single day! - with bulldozers ... and the houses (flashy shacks) that are being built in a day along these roads (within earshot of Careladen) breaks my heart. HELL is here and now in all its Dante-terror".

In 1949, Graves exhibited at the XXIV Venice Biennale while also featuring in a traveling exhibition, Milestones of American Painting in our Century, organized by Boston's Institute of Contemporary Art. However, by the end of the decade Graves's stellar position in the New York art world was starting to fade as a result of the of rise of the New York School The New York critics had begun to disparage his work. Sam Hunter suggested that his painting lacked depth and was "more [...] autohypnotic hallucination than metaphysical revelation", while Robert Coates of The New Yorker wrote that "one feels that underneath the surface charm there is only emptiness, or at most, a thin, vaporous mysticism".

A despondent Graves traveled to England in the fall of 1949 as the guest of British art collector Edward James. James offered Graves a commission to paint murals in lunettes at his mansion at West Dean Park in Chichester, West Sussex. Although he declined James's offer, Graves stayed with his host for more than a month before crossing the English Chanel to Chartres in France. Renting three rooms in a seventeenth-century abbot's residence, he spent three months there in near solitude. He painted at Chartres Cathedral every day, describing it as "a great diagram of how to enter heaven" but rued that to gain entry to heaven "requires tremendous skill, and this I must acquire through the act of painting".

Returning to Seattle in 1950, he destroyed most of his Chartres works (Willis, one of the few to see the Chartres pieces, stated that "the work was sort of hard drawings and a few paintings of gargoyles; in fact nothing that I wanted him to show to anyone") and would fly into a rage when his paintings did not find a buyer. Although Willis continued to sell works by Graves (and Tobey) in Seattle and New York, demand for his work started to decline. "He was never the same again", suggested Willis, "All the old and beautiful sensitivity had faded, the Inner Eyes, the consciousness, all that was gone".

Late Period

The completion of Careladen took up most of 1952 and, in the spring of the following year, Graves staged an event that might be described in the future as a "happening". He sent invitations to everyone on the Seattle Art Museum mailing list. The invitation read: "You or your friends are not invited to the exhibition of Bouquet and Marsh paintings by the 8 best painters in the Northwest [The eight included Graves's friends and neighbors Clayton and Barbara James] to be held on the afternoon and evening of the longest day of the year, the first day of summer, June 21, at Morris Graves' palace in exclusive Woodway Park. Refreshments will be served".

Guests, some arriving in formal evening wear, found the driveway blocked by a trench. A banquet table with a 10-day-old turkey feast was drenched by a garden sprinkler as mood music and farm animal sounds played over speakers. With Graves and his cohorts refusing to answer the door, guests, some amused and others irritated, responded by storming off, sketching the scene, or stealing silverware from the table. Graves observed the chaos through a gap in the cinder-block wall. Ament wrote: "The principal casualty of the evening was Graves's friendship with Clayton and Barbara James, whose names he had added to the invitation without consulting them. They were not amused. In addition to having dug a trench to cross the access road, he had put coiled barbed wire on the ground between his place and the James's house. They were so offended that they put a painting he had given them inside the barbed wire and severed their friendship".

In September 1953, largely due to the efforts of Seattle gallery owner Zoe Dusanne, Life magazine ran a major article on the "Mystic Painters of the Northwest". It focused on Graves, Tobey, Anderson and Kenneth Callahan. By this time, however, the four men were barely on speaking terms. Callahan in particular was furious with Graves for dodging military service and took Tobey's side against him. Meanwhile, Life depicted Graves as a hermit and mystic: "When he is not creating [...] he devotes himself to the forest hideaway, potting gnarled, dwarfed trees, pushing huge rocks into strange formations, tending his flock of exotic fowl or merely sitting, contemplating new visions of the inner eye". The piece cemented Graves's place as an artist of national importance. But Willis noted that "When he became famous [Graves] lost all need for his beloved role as exhibitionist. The poverty-struck saint was also out of order. Further than that was the deadly, deadly fear that he could not create - knowing that his way of life had finally murdered the beautiful innocent generous child within him - the child who identified himself with absolute directness to every aspect of nature".

Graves believed his happiness and survival depended upon self-isolation and he could no longer tolerate life at Careladen (he sold the property in 1957). After a five-week spell in Japan, he moved to Ireland in 1954. Graves lived in various parts of the country before buying Woodton Manor (with the proceeds from Careladen), a dilapidated 18th century house near Dublin in 1958. Having spent a year restoring the property, Graves painted a collection of fantasy-folk creatures that became known as his Hibernation series. He was fascinated with the night sky and stories of space exploration, leading subsequently to "Instruments for a New Navigation", a collection of precisely rendered totemic bronze, glass, and stone sculptures inspired by the dawning Space Age. (Failing to find a market for these unusual celestial pieces, he dismantled them and did not display them again until 1999.) In 1957 Graves became the first US artist to receive the Windsor Award, bestowed by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and in 1962, as the guest of Indira Gandhi, he visited India where he met with Indira's father and the Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

Graves sold Woodtoown Manor in 1964 and destroyed much of the work he had done there before returning to the US. He stayed briefly in Seattle before buying another property, this time in Loleta, 18 miles south of Eureka, Northern California. The farmhouse was situated beside a small lake, in a forest of old-growth redwoods. "Something about these great old mature giant trees makes my heart go out to them", Graves wrote to his mother, "I love them more than my fellow man". Following the design pans of the Seattle architect Ibsen Nelsen, Graves built a secluded cottage - called "The Lake" - at the end of a narrow dirt road leading into the forest. The art critic Gino Pennacchietti suggested that Graves's story was very similar to "other deep ecologists and artists/thinkers who are connected to the natural world, and [who] choose to exist in a state of perpetual sauntering through the wilderness". In this respect, Graves followed the example of "Emerson and Thoreau [who] set out the archetypal template in the American experience of this way to think about nature and living harmoniously with the land".

The move to Eureka marked a dramatic shift in Graves's paintings. He would spend the remaining 35 years of his life a near recluse, observing the wildlife and watching sunrises and sunsets. Many of his paintings in his final years were of his own simple flower arrangements, marking a dramatic shift from the metaphysical bent of his earlier works. As Ament observed, "Gone were the black and gray washes [and in their place were] still life paintings that glowed with incandescent yellows, and rosy pinks, and deep, jewel-like carmine".

Although a sign posted at the entrance to his cottage read "No visitors today, tomorrow, or the day after", Graves occasionally allowed welcomed family members and old friends. One rare public outing was a music/dance collaboration, Inlets, in 1977, with John Cage and the choreographer Merce Cunningham. Graves's stage design for Inlets consisted of a large disk that moved slowly across the back of the stage, evoking the atmospheric cycle of a moon. In the last decades of his life he returned to his treasured theme of birds producing notable tondos works such as Spirit Bird and Waking, Walking, Singing in the Next Dimension in chalky circular sweeps. Graves died peacefully at home on May 5, 2001, just a few hours after suffering a stroke.

The Legacy of Morris Graves

The film director John Huston, who lived near Graves while in Ireland, described him as "the last living legend of the American West - the archetypal hermit of the wilderness". Indeed, in spite of his extraordinary critical and commercial success during the 1940s and early 1950s, Graves remained the quintessential artistic outsider who exerted little direct influence on the grand narrative of modern art. He was even damned with praise by the British art critic and painter Patrick Heron who called him a "charming illustrator". Graves was perhaps too individualistic to make a significant impact on any one movement or major figures, however, echoes of his work can be found in many Northwest artists including Jay Steensma, Nicholas Honshin Kirsten and Elizabeth Sandvig.

Graves's personification of the "artist-shaman" did, however, see him emerge as an important figure for the 160s counter-culture movement. Joseph Beuys would embrace the same persona and was fully aware of Graves's work through his interactions with John Cage in the early 1960s Fluxus movement. The painter and paleontologist Wesley Wehr was another admirer. He wrote that Graves's paintings "were not only beautiful aesthetic objects; they were, for me, paths to other kinds of personal knowledge and living". The poet Kathleen Raine said Graves caught "the essence of the very soil of America [...] an example of the new beauty attainable when that union is authentic and profound". On a slightly more irreverent note, a modern-day Dadaist brotherhood, who went by the name "The Mystic Sons of Morris Graves", paid homage to the artist by staging events such as the "Glorious Ruins Raffle", in which chances were sold to smash "a priceless piece of art glass by Seattle's renowned media darling, Dale Chihuly".

Influences and Connections

-

![John Cage]() John Cage

John Cage - Guy Anderson

- Dr. Richard Fuller

- Lubin Petric

- Nancy Ross

-

![Art Deco]() Art Deco

Art Deco -

![Dada]() Dada

Dada -

![Japonism]() Japonism

Japonism -

![Surrealism]() Surrealism

Surrealism - Zen Buddhism

-

![Joseph Beuys]() Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys - Fritz Bultman

- Jay Steensma

- Nicholas Honshin Kirsten

- Elizabeth Sandvig

-

![Merce Cunningham]() Merce Cunningham

Merce Cunningham ![Edward James]() Edward James

Edward James- Zoe Dusanne

- Ibsen Nelsen

- John Huston

Useful Resources on Morris Graves

- Morris Graves: Vision of the Inner EyeRay Kass (New York, George Braziller, 1983)

- Iridescent Light: The emergence of Northwest ArtBy Deloris Tarzan Ament

- Morris Graves: His Houses, His GardensBy Richard Svare

- Bachelor Japanists: Japanese Aesthetics & Western MasculinitiesBy Christopher Reed

- Morris Graves: Vision of the Inner EyeBy Ray Kass

- Morris GravesBy Frederick S. Wright

- Morris Graves: The Early WorksBy Theodore F. Wolff

- Morris Graves: The Flower PaintingsBy Theodore F. Wolff

- The Drawings of Morris GravesBy Ida E. Rubin, editor

- Calix, Cup, Chalice, Grail, Urn, Goblet: Presenting the Sexual Essence of Morris GravesBy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York

- Northwest Mythologies: The Interactions of Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan and Guy AndersonBy Sheryl Conkelton & Laura Landau

- Sounds of the Inner Eye: John Cage, Mark Tobey and Morris GravesBy Wulf Hurzogrenrath & Andreas Kruel

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI