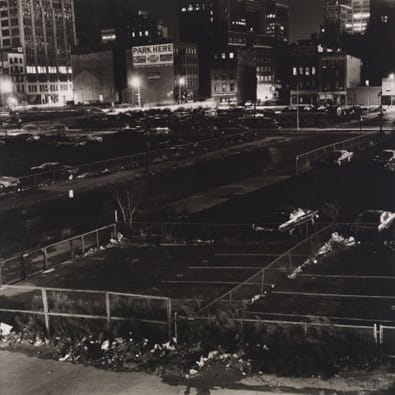

Summary of Peter Hujar

Peter Hujar is now widely acclaimed for his black and white portraits of New York's bohemian East Village community, taken between the late 1960s and early 1980s. While an overview of his work reveals Hujar's mastery of other photographic genres - notably animal portraiture, and nocturnal street-photography - it was for his ability to tease out the psychological vulnerability of his sitters that set him apart from his contemporaries. Given that they were gay men whose lives were often cut short by the 1980s AIDS epidemic, many critics and historians focus on differences between Hujar's humanist outlook and the more formal/studio-based style of Robert Mapplethorpe. Unlike Mapplethorpe, Hujar refused to court publicity and remained wholly indifferent to the commercial demands of the New York art market. Admired by fellow artists for staying true to his artistic convictions, Hujar is also celebrated for a darkroom prowess that lends his images a truly rarefied print quality.

Accomplishments

- Hujar portraits - many featuring damaged and emotionally fragile characters caught contemplating their own mortality - are remarkable for their subtle blend of humanism and unvarnished authenticity. Hujar held a deep distain for overly-staged compositions, preferring an unobtrusive camera technique that always allowed his subjects to "own the image".

- Although it seriously stymied his own career progression, Hujar's uncompromising attitude towards photographic art (and avant garde art in general) provided inspiration for many younger artists. Nan Goldin and David Wojnarowicz looked up to Hujar as a highly principled artist who set an example to others through his stubborn refusal to give onto the demands of the commercial art world.

- Hujar gravitated towards the derelict haunts and dilapidated dwellings of the bohemian downtown milieu - where he also lived. "My work comes out of my life", he proudly stated. Peter Schjeldahl, art critic for the New Yorker, perfectly summed at Hujar photography when he said it stood at "a historic crossroads of high art and low life in the late twentieth century".

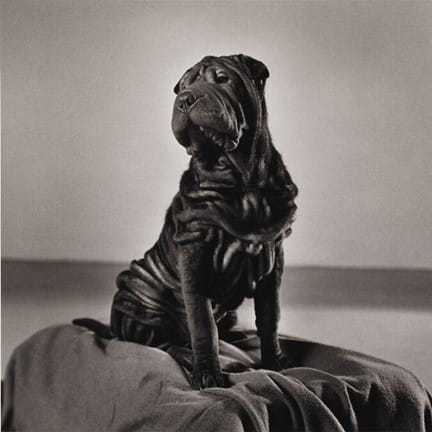

- Many have observed that Hujar treated his animal subjects with the same gravitas and technical perfection that was the trademark of his human portraits. Critics and fellow photographers have singled out works such as Will (1985) (a Shar Pei breed of dog) for the way Hujar seemed to possess an innate understanding of animals which he captured in a uniquely personable way.

The Life of Peter Hujar

Susan Sontag wrote, "Fleshed and moist-eyed friends and acquaintances stand, sit, slouch, mostly lie - and are made to appear to meditate on their own mortality ... Peter Hujar knows that portraits in life are always, also, portraits in death".

Important Art by Peter Hujar

Smiling Girl, Southbury

Between 1956 and 1958, Hujar visited homes for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Southbury, Connecticut and in Florence, Italy. His friend, and director of the Peter Hujar Archive, Stephen Koch, called the resultant images "[Hujar's] first set of really masterful work". Smiling Girl, Southbury (1956) captures a group of girls at play in the grounds of the Southbury Training School. The three girls to the left, look outside the frame as if observing someone engaged in an exercise or game. Closest to the camera, slightly to the right of center, is a girl who engages Hujar's camera with a beaming smile, while a classmate is seen behind her also grinning at the photographer. Alluding to Hujar's observational style, Novelist Hanya Yanagihara suggests that these photographs "are remarkable for their self-assurance and clarity of vision, not to mention the matter-of-factness of their gaze".

For the art critic Brian Sholis, these works were early indicators of Hujar's worldview. He wrote, "Neither sentimental nor aggressive, these small black-and-white images possess the empathy and compositional rigor we associate with Hujar's unruffled portrait work of the 1970s and '80s. [...] Hujar recognizes in each child an essential human dignity that, I think, would escape most of us, with our cultural biases and reflexive attunement to difference. (This openness would serve him well in later decades as he photographed the eccentric figures of the downtown demimonde.)". Commenting on these images (and similar portraits he made of outpatients attending a Bronx mental health clinic), meanwhile, Koch wrote, "Peter believed that there are in the world certain exceptionally favored people who live entirely in the present - unlike himself, unlike most of us, but perhaps like these children. Emotionally, in their essential being, they never absent themselves; they are always fully here. They are present for everything".

Gelatin silver print - Matthew Mark Gallery, New York

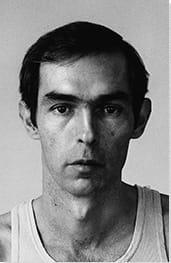

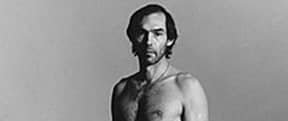

Nude Self-Portrait, #3

Hujar's Nude Self-Portrait series formed as part of his portfolio application to attend a prestigious "Master Class on Photography" run by the legendary fashion photographer, Richard Avedon. Although he had already been working in commercial photography, Avedon's Master Class convinced Hujar that his future was in art photography (rather than in commercial work). In this black and white image, a naked Hujar is seen at a distance from the camera in a stark, unadorned studio. He stands on one leg; his body contorted and his head thrusting downward, as though caught in the middle of a ritualistic dance. The photograph is playful, yet also intimate and dark, with his head and face rendered almost in silhouette.

Arts writer Mark Alice Durant said of this series: "With echoes of Eadweard Muybridge and influenced by recent encounters with Yvonne Rainer's Judson Dance Theater, the photographs have a coolness and raw physicality that hint at some of the qualities that characterized his later work". Hujar activates the empty space of the room with his body, much as the Conceptual and Performance artist Bruce Nauman had done in works such as Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square (1967-68) (it is unknown whether the two artists were aware of each other's work). Moreover, this work stands as an early indicator of Hujar's dark room talents. As curator Olivia McCall argues, Hujar "was such a master printer that few, honestly, can compare to the work that he did in the dark room and the way that he brought out emotional depth through the way that he printed the photograph, and the way that he emphasized the tonalities of the image, he really brings out an intimate narrative that speaks to knowing someone quite deeply".

It would be another decade before Robert Mapplethorpe (the photographer with whom Hujar is habitually compared) turned to "erotic" self-portraiture as the central theme in his work. But, as Hujar's friend and social commentator Fran Lebowitz, recalled, "Peter and I shared the distaste for Robert. [One] of the reasons is that Peter thought Robert was silly, you know, which he was. And he thought that Robert copied him in certain ways, which of course he did".

Gelatin silver print - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

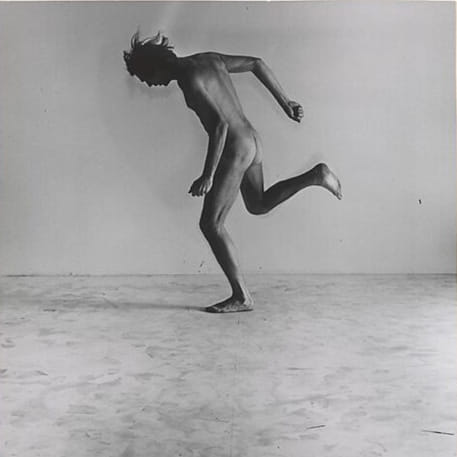

Candy Darling on Her Death Bed

Some of Hujar's most famous portraits were of the "transgender superstar", Candy Darling. This image was captured at Columbia University Medical Center in New York, shortly before her passing from cancer in 1974 (aged just twenty-nine). Having formed their friendship in the 1960s at Andy Warhol's Factory, they bonded over their unhappy upbringings: Darling, born in 1944 as James Slattery, had, like Hujar, had to deal with a violent alcoholic upbringing, while both had to deal with homo/transphobic prejudices. Darling had enjoyed a degree of stardom, appearing in a number of underground films produced under the creative umbrella of the Factory (such as Paul Morrissey's Flesh (1968)). However, in 1972 Warhol told a devastated Darling that he wanted films that replaced "chicks with dicks" with "real women". As arts writer Amelia Rina explains, "[Soon after this news] Darling was diagnosed with lymphoma. Those close to her suspect it was caused by the hormones she took to grow breasts - at Warhol's suggestion. In the ultimate tragedy, it may have been her effort to transform into what she believed was her true self that killed her".

Rina says of Candy Darling on Her Death Bed: "Hujar expertly rendered the high contrast between the darkened room, Darling's alabaster skin, her dark shirt, the white hospital bed sheets, and the fluffy white chrysanthemums floating on a darkened back wall, recalling the classic Hollywood glamour she loved so dearly. [...] In her reclined pose, common to Hujar portraits, Darling looks as though she could be relaxing in her own bed if it were not for the strange sterility of the hospital room décor. With her perfectly applied make up and famously blond hair, Darling looks ready to go to a party, but upon remembering her illness, her dark eye make up and angular physiognomy turn her face into a skull, prophesying her impending death. The image complicates its viewing - continually shifting between seducing with its beauty and repelling with its morbidity. [Hujar] captured this confusion of expectation, reality, and fantasy that permeated Darling's entire life with an eloquence that no one else could have matched".

Gelatin silver print - Tate Modern, London

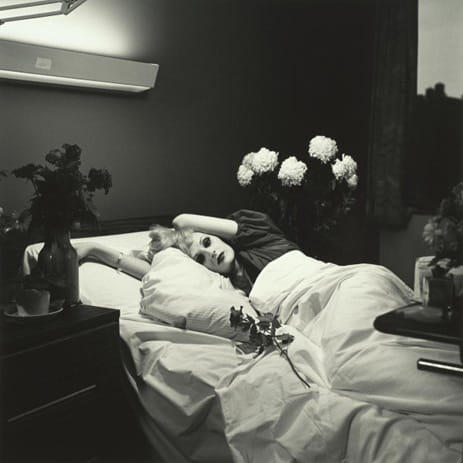

West Side Parking Lot, NYC

Hujar produced many shots of the streets, parks, and piers of New York City. These works are commonly referred to as his "queer city" photographs. His nocturnal street photographs typically captured images of men cruising for homosexual encounters in public spaces, many in Stuyvesant Square Park just a few blocks from Hujar's loft on Second Avenue, and on the abandoned piers along the Hudson River. Artist and writer Mark Alice Durant argues that "Hujar's restlessness led him to wander beyond the confines of the studio. Like Brassai, Hujar was a poet of the urban nocturne, prowling the streets with his camera as the day unraveled. Brassai's Paris is gritty, erotic, sentimental, yet impersonal. Hujar's photographs of New York's streets at night embrace emptiness and furtive gestures, glowing skyscrapers, assorted rubble, discarded rugs, boys in drag, and girls passed out in his doorway. His nighttime images of the Hudson river are disquieting, suggesting powerful currents not fully understood by the dappled surfaces".

While most of his queer city works were of young party-goers and gay men cruising for casual sex, West Side Parking Lots (1976) is devoid of a human presence. Writer John Douglas Millar observes that there is "a queer joke embedded in this picture: the words 'park here' printed on the building top-left, and below them the word 'leather.' These parking lots were a cruising ground for gay men in the 1970s, and they were near the infamous leather club The Mineshaft, which was located at 835 Washington Street". Hujar's friend and photography critic Vince Aletti adds that "In many ways Peter Hujar defined downtown for me. He went places I never dared to and hung out with people I'd only read about". Lebowitz, too, stated that Hujar "took me to places taking photographs where I never, ever would have gone. [...] Peter was physically fearless in the city, that's for sure, when there were plenty of places that were dangerous to go in New York".

Gelatin silver print - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

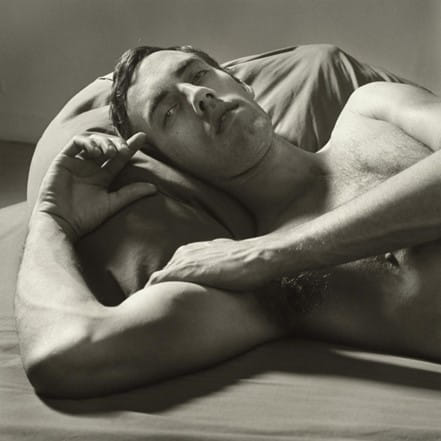

David Wojnarowicz Reclining (II)

One of Hujar's favorite models was his one-time lover, and long-time friend and protégé, the painter and photographer David Wojnarowicz. The two had met around 1980 in a bar where Wojnarowicz was working as a hustler. Art critic Peter Schjeldahl writes, "Wojnarowicz said that Hujar 'was like the parent I never had, like the brother I never had.' In return, he inspired fresh energies in Hujar's life and late work". Here Hujar frames Wojnarowicz from the chest-up, as he reclines on a mattress on the floor, with his head resting on a pillow. Wojnarowicz's index finger points toward his temple, while his left arm folds across his naked chest, with his left hand gripping his right bicep (thereby underlining his masculinity). He gazes directly into the camera, with an expression that emphasizes his personal connection with the photographer. Koch said of Hujar's portrait, that " [he knew] how to make people look great [...] David was a perfectly okay person, but a young god from Mount Olympus, he was not [...] except Peter made him look like that and knew exactly how to do it".

Hujar's sitters would recall how he was adept at coaxing them to "open up" in front to the camera through sweet-talk. Photographer Gary Schneider recalls that, both in and out of the studio, "Hujar made everyone feel like you were his only friend, and that was very flattering". Photographer Nan Goldin stated that "[Hujar's] pictures are exotic but not in a shallow, sensational way. Looking at his photographs of nude men, even of a naked baby boy, is the closest I ever came to experience what it is to inhabit male flesh". Yet viewing his intimate shots of Wojnarowicz today, we can read an additional layer of sad poignancy. At the time of their creation, Hujar knew he was going to die as a result of his HIV/AIDS diagnosis. It was a fate that also awaited Wojnarowicz who succumbed to the disease five years after his friend and mentor.

Gelatin silver print - The Tate, London

Will

Although best known for his portraits of human subjects, Hujar is also widely admired for his masterful photographs of animals. Hujar's earliest animal photograph dates back to 1969 with a portrait called Horse in West Virginia Mountains. In what was an indication of what was to come, the image, featuring a short stout horse, pictured in profile against the backdrop of a foggy mountainous landscape, captured something of the creature's personality. Critic and curator Abigail Solomon-Godeau said that when Hujar first showed her his animal prints "[She] was stunned, not because of their manifest formal perfection but by their quality of austerity, their evocation of inwardness and interiority, and especially, their gravitas, a gravitas as much in evidence in his pictures of animals as in his human sitters". Produced some 16 years after Horse in West Virginia Mountains, Will, a dark-colored Shar Pei dog, stands as Hujar's most famous animal portrait.

Sat obediently in a studio, Will is placed in a simple setting, against a blank wall, and seated atop draped fabric. Will conveys something of the animal's unique personality, and also display's Hujar's sublime darkroom technique, here emphasizing the contrasts that highlight the sharply-defined dog against the soft-focused background. Hujar lends Will a true sense of canine majesty. Hujar's friend, the photographer Gary Schneider, stated that he and Hujar thought Will was such "a pretty image" they decided to produce exclusive prints to give as gifts to people like the doctors who were or had been treating, or had treated, Hujar's HIV/AIDS diagnosis. Schneider recalls Hujar making aesthetic decisions in the printing of the image, such as making it "slightly haloed around the dog" and dictating the specific quality of blacks that were to be achieved, so as to add a sense of "brightness". Goldin called Hujar "the best photographer of animals I've ever met" adding that he approached his animal subjects with the "same rare empathy" one could see in his "highly personal [human] portraits".

Gelatin silver print - Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Biography of Peter Hujar

Childhood

Peter Hujar was born in Trenton, New Jersey, to Rose Murphy, a waitress who worked tables in Lower Manhattan. His father, Joseph John Hujar, was a bootlegger who abandoned his mother before their son was born (father and son would never meet). Without the financial means to properly support him, Rose sent her son to live with his Ukrainian grandparents on their farm in neighboring New Jersey. He spent these formative years in the care of his grandparents, both of whom spoke no English. In 1946 (following the death of his grandmother), Hujar moved to New York City where he lived with his mother and her second husband. Having been handed down a camera by Rose in 1947, the twelve-year-old Hujar was determined to pursue a career as a photographer. His friend, the writer Linda Rosenkrantz, describes how he came to view his mother as a "neglectful and abusive alcoholic who had abandoned [him] as a child [and] then threw a gin bottle at him when he was 16 at which point he left her domicile forever". (Rosenkrantz adds the footnote that while he was "undeniably conflicted and resentful" towards Rose, "he did care about her".)

Education and Early Training

In 1953, Hujar enrolled at the School of Industrial Art, in Manhattan. At this time he was drawn towards fashion photography, such as that routinely featured in up-market magazines such as GQ and Harper's Bazaar (it would not be long before he worked, albeit briefly, for both publications). Hujar also habitually frequented photographic galleries in Greenwich Village and larger institutes such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Through these visits he became especially captivated by the "gritty" street portraiture of Lisette Model. Of his own efforts, meanwhile, Hujar's creative writing teacher (at the School of Industrial Arts), the poet Daisy Aldan, offered him great encouragement and reassurance (and even allowed a temporarily homeless Hujar to sleep on her couch). New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl called Aldan a "free-spirited lesbian" who implored Hujar to pursue his dream at all costs: "Peter. You are an artist - you don't know it yet, but you are. And you will be one until you die. [...] You must go out and find the ten most important commercial photographic studios in the city. Knock on the door and ask for a job doing anything. Sweeping the floors, if necessary". Following Aldan's advice, Hujar got his first foothold in the industry by working menial jobs (including walking his boss's dog) in a number of commercial studios.

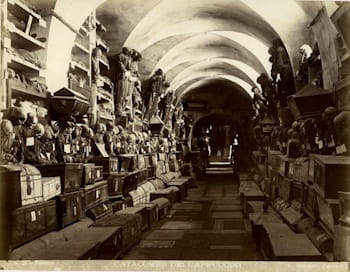

In 1958, Hujar travelled to Italy with the artist Joseph Raffael who was visiting the country on a Fulbright scholarship (the scholarship was awarded as part of a cultural exchange program between the US and Italy). Hujar secured his own Fulbright scholarship in 1963, and returned to Italy with his then lover, the artist Paul Thek. Art critic Alex Needham called the Hujar's photographs of the Capuchin Catacombs in Sicily as "a dozen startling shots of 17th-century skeletons in their graves, taken in 20 minutes".

Soon after arriving back in the US (in 1964), Hujar became chief assistant in the commercial photography studio of Harold Krieger. He also made the acquaintance of Andy Warhol and began to hang-out at Warhol's Factory (where he mingled with "outsiders" such as transgender actress Candy Darling and drag artist Jackie Curtis). Hujar posed for four of Warhol's Screen Tests (1963-66). The Screen Tests were a series of three minute black and white films, featuring hundreds of individuals (and later projected in slow-motion) showing the subject (directed by Warhol to remain motionless) from the shoulders up, against a plain photobooth-like backdrop. Hujar appeared in Warhol's film, The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys (1964) which was compiled from the Screen Tests series.

Hujar was by now open about his homosexuality, and for a while, was in sexual relationships with Raffael and Thek simultaneously. In 1967, Hujar attended (with the likes of Alexey Brodovitch and Diane Arbus) a master class on fashion photography taught by photographer Richard Avedon and art director Marvin Israel. Although Hujar enjoyed the class, he took the decision there and then to commit fully to the idea of legitimizing the photographic medium as a modern artform. As Koch explained, "Peter never doubted for one second that photography was art. It is true that a lot of people had different ideas, that it was not seen as art and it was not valuable. I remember a time when you could buy a print of the Jewish giant by Diane Arbus for $500 easily. Peter didn't accept such a thing".

Mature Period

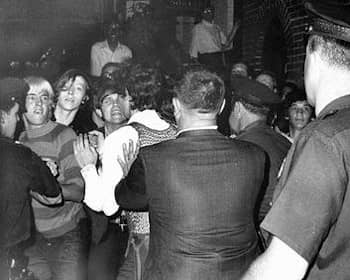

Hujar produced photography for the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) magazine, Come Out! - "A Newspaper By And For The Gay Community" - that published (over eight issues) following the Stonewall Riots of 1969. However, it was the only time that Hujar's art and sexual politics explicitly overlapped. In 1969, Hujar shot a series of photographs of men at the peak of orgasm.

Moving into the early 1970s, Hujar started collaborating with artist Stephen Lawrence on the publication of a textless journal called Newspaper which "championed a method of chaotic reading of images". Writer John Douglas Millar explains that "The journal looks like a conceptual object. Images from gay and straight porn, mainstream and countercultural news media, advertising (sometimes commissioned adverts, though they are placed within the journal without being obviously so), work by artists including - amongst many others - Paul Thek, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Ray Johnson, Andy Warhol, Yayoi Kusama, Peter Beard and, in every issue, several images by Hujar himself, are arranged within the foundational structures for Minimalism and Conceptualism, the series, and the grid".

In 1973, Hujar moved into a loft apartment (the previous occupant was the pansexual underground actress, Jackie Curtis) above the Eden Theater in New York's East Village. He spent the rest of his career photographing the artists, drag queens, and other bohemian characters who populated the neighborhood. The Art Institute of Chicago (AIoC) writes, "Hujar would go on to photograph extensively the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, an absurdist project founded by [playwright] Charles Ludlam, and The Cockettes, a psychedelic theater troupe based in San Francisco. Hujar photographed performances by these companies but often paid more attention to capturing the actors and dancers backstage, in moments of transition - as they put on their costumes and make-up, preparing to embody the characters they would play". Hujar would also venture (with his camera) into S&M clubs and visit the abandoned piers on the west side of the Hudson River where gay men would meet for illicit sexual encounters.

Late Period and Death

In 1975 Hujar's first book of photographs, Life and Death, was published. It included several of his Palermo catacomb shots and boasted an introduction by the renowned critic, Susan Sontag. Koch notes, however, that when Sontag produced her own book, On Photography, two years later, two things irked Hujar: "First, he wasn't mentioned, and he absolutely believed, and he probably was right, that he just wasn't famous enough, even though she knew how good he was. The other thing was that it raised questions about whether photography is or is not an art, and that was a fatal error that he would absolutely not accept. At one point he quoted having been in the conversation with Richard Avedon [who said to him] 'You know, Peter, there are times when I wonder if maybe Susan is the enemy'".

In 1981, Hujar met the young gay artist David Wojnarowicz. After a brief period as lovers, the two men settled into a platonic relationship that was part friendship, part mentorship. Koch writes, "Peter was almost uniquely serene and open about being gay. He wasn't aggressive about it. He didn't preach or overstate his identity, but nothing about being gay made him ashamed, or secretive, or uptight. This was very unusual. Especially in those days, most gay people went through some sort of personal or social trauma learning to cope with their otherness, and they had scars that showed. The two men differed, however, in their commitment to gay activism, with Wojnarowicz aggressively advocating for AIDS awareness".

Hujar was diagnosed with AIDS in January 1987 (after which, he would never take another photograph). The timing of his diagnosis overlapped with that of fellow queer photographer, Robert Mapplethorpe. Koch writes, "When they were dying, the photographer Lynn Davis used to move back and forth between their places every day. And when she arrived, they always asked, 'How's the other one?' Peter died fairly long before Robert [March 1989]. Robert used every conceivable medical device he could find to just keep breathing, whereas Peter, I wouldn't say he accepted death, but it came to him in a lot more natural way". In accepting the inevitability of his passing, Hujar told Koch (in a statement that now reads as not a little ironic), "I have decided I want two graves. [...] There should be one grave for me. The other grave should be for my work. [...] I'm not gonna let them make me famous after my death".

Hujar died on November 25 of 1987 at the Cabrini Medical Center in New York. Wojnarowicz photographed his friend, mentor and former lover on his death bed. His funeral was held at the Church of St. Joseph in Greenwich Village, and he was buried at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. Hujar bequeathed his estate to Koch, who later reflected that, "in a way, he was famous. But it was a very odd fame. I am tempted to call it a kind of secret fame. His reputation was simultaneously widespread and covered; at once powerful and almost invisible. [...] In that glamorous but secret place he had made his own, he stepped - incognito, as it were - into his authentic eminence".

The Legacy of Peter Hujar

Hujar has at last received the recognition he deserves. He was a significant figure within the New York's queer art scene between the late-1960s and mid-1980s and his images of East Village bohemians, not to mention his nocturnal street scenes and animal portraits, have secured him a reputation as an unobtrusive and empathetic chronicler whose technical mastery in the dark room was unequalled. His friend and biographer Stephen Koch writes, "The camera was Peter's instrument of intimacy. Its lens gave him something he could not otherwise achieve and could not live without: an equilibrium between closeness and distance". Sir Elton John (whose photography collection totals more than 7,000 pieces and is one of the largest private collections of photography in the world) has commented that Hujar's "humanity, depth and sensual insights aren't for everyone, and don't need to be, but once his pictures get into your bloodstream they are impossible to shake".

It is well known that Hujar fame was (and continues to be) overshadowed by Robert Mapplethorpe (a photographer whose work Hujar once dismissed as "silly"). Curator Joel Smith suggests that "Part of the reason [Hujar] was eclipsed was because of the great success of Mapplethorpe, who filled a niche and very spectacularly filled the image of a bad-boy photographer privy to those kinds of secrets of dark, nighttime gay lifestyle. It was easy for the mainstream culture to think of [the publicity shy Hujar] as 'the other one,' or 'the minor one.' He did not have Mapplethorpe's knack of promoting himself". But commenting on the commercial failure of Hujar's (only) book, Portraits in Life and Death (1976), art critic Alex Needham wrote, "[today the book] is recognised as not only a priceless document of a vanished culture, but as a collection of some of the finest portraits ever taken. Hujar insisted on printing all his pictures himself, and his meticulous efforts in his darkroom on Second Avenue resulted in black-and-white images that marry psychological acuity with flawless technique".

Influences and Connections

-

![Richard Avedon]() Richard Avedon

Richard Avedon -

![Lisette Model]() Lisette Model

Lisette Model - Marvin Israel

-

![David Wojnarowicz]() David Wojnarowicz

David Wojnarowicz -

![Alexey Brodovitch]() Alexey Brodovitch

Alexey Brodovitch -

![Diane Arbus]() Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus ![Susan Sontag]() Susan Sontag

Susan Sontag- Candy Darling

-

![David Wojnarowicz]() David Wojnarowicz

David Wojnarowicz -

![Alexey Brodovitch]() Alexey Brodovitch

Alexey Brodovitch -

![Diane Arbus]() Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus ![Susan Sontag]() Susan Sontag

Susan Sontag- Candy Darling

Useful Resources on Peter Hujar

- Peter Hujar's DayBy Linda Rosenkrantz

- Peter Hujar: Speed of LifeOur PickBy Philip Gefter, Joel Smith, Steve Turtell, and Martha Scott Burton

- Portraits in Life and DeathOur Pick

- NewspaperOur PickBy Peter Hujar, Steve Lawrence, and Andrew Ullrick

- Peter Hujar Curated by Elton JohnOur PickBy Elton John

- The Shabbiness of BeautyBy Moyra Davey

- Peter Hujar: NightBy Bob Nickas

- Peter Hujar: Lost DowntownBy Vince Aletti

- Peter Hujar: Love & LustBy Jeffrey Fraenkel

- Changing Difference: Queer Politics and Shifting Identities: Peter Hujar, Mark Morrisroe, Jack SmithOur PickBy Lorenzo Fusi, Marco Pierini, Bill Arning, and Fiona Johnstone

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI