Summary of Menashe Kadishman

Despite a wide-ranging body of work, Kadishman remains best known as the sculptor and painter who introduced the seemingly innocuous motif of the sheep to the fine-art domains of Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and Neo-Expressionism. It was a unique thematic and formal combination that prompted the American art critic and poet Donald Kuspit to describe his art as "high-culture kitsch". Having built his reputation during the 1960s and early 1970s in England and America, he took the decision to return permanently to his homeland of Israel (to the detriment perhaps of his international standing) where he became absorbed in the themes of Jewish heritage and familial sacrifice. Kadishman typically approached these complicated topics through atheistic variations on the story of Isaac as told in the Hebrew Bible.

Accomplishments

- Kadishman's most iconic works stemmed from the artist's years working as a shepherd on a kibbutz. The sheep/ram became the major motif in his work and spoke of his fascination with the merging of man and his environment, the meeting of the industrial and the organic, and the symbolic significance of the ram in biblical storytelling. Kadishman's fascination with the animal led ultimately to a range of vividly colored "sheep portraits" that some critics have likened to the best portraits by Andy Warhol.

- In his early Minimalist sculptural phase, Kadishman focused largely on formal issues and the tension and balance between constituent materials. As his career developed, however, he moved towards a looser, more expressive style of sculpture. He earned special recognition for a monumental style of steel "cut-out" silhouettes that closely mimicked techniques more readily associated with line drawing.

- Kadishman's most famous installation, Shalechet (Fallen Leaves), features a walkway of metal disc "faces" that "crunched" when walked upon. It was first-and-foremost a memorial work that invoked the Shoah (Hebrew for the Holocaust) with the sound of metal-on-metal simulating the sounds of forced labor and the arrival of deportation trains. But Kadishman thought of himself as essentially a humanist whose work conveyed a more universal message; that is one that decried all violence and human suffering while speaking at the same time of hope for a peaceful future for his country.

The Life of Menashe Kadishman

Former shepherd Kadishman, who once stated, "sheep are a part of me", used his art to imbue the animal with a holy-like reverence: "I feel like every [image of] sheep hanging at home is like an icon of Saint Mary hanging in a Christian home".

Important Art by Menashe Kadishman

Suspense

Suspense is representative of Kadishman's minimalist period of mid 1960s, which was characterized by seemingly gravity defying structures. The artist developed this sculptural style while studying and living in London. He was influenced by the English abstract sculptor Anthony Caro, under whom he studied at St Martin's School of Art, and other members of the New Generation of British Minimalists in the 1960s. The idea for this sculpture can be traced back to sketches he made in 1963 and from which he created his first model in wood and stone. A second version was created in stone for his first solo show at London's Grosvenor Gallery in 1965. The following year, the Israel Museum commissioned Kadishman to create a larger version for the Museum's new art garden to be made in steel and, later, painted yellow.

Unlike his contemporary, the American Robert Morris, who was producing Minimalist sculptures that were at this time concerned purely with the work's formal arrangement, Kadishman's goal was to create a work that related directly to its context, in this case the desert landscape. In a desert environment, rocky masses, eroded by wind and water can topple over under the slightest movement. This sense of suspense is translated to the sculpture through the long rectangular segment that appears to be balanced precariously on top of the structure. The artist painted the sculpture in bright yellow inspired by "the color of the tractor in nature". In this way, he simultaneously referenced the natural environment and human interactions with nature. The Israeli author and scholar Gideon Ofrat added that "this modernist sculpture, autonomous in its abstract forms" also invoked "an ancient ritual [whereby] the dialectics of Israeli identity [...] unify the conflicts of the past and the future, the ancient and the progressive [and] the local and the universal".

Painted Steel - Israel Museum, Jerusalem

The Three Discs (Uprise)

Of the many examples of public art created by Kadishman, his monumental sculpture The Three Discs (Uprise) is probably his most iconic. Located at the Habima Square in the heart of Tel Aviv, it is now considered an important city landmark. Composed out of three large steel discs placed atop one another, the structure tilts at a 55° angle and reaches a height of 12 meters. The sculpture's power lies in its dynamic composition and gravity-defying quality. Depending on the viewer's vantage point, the diagonal motion can evoke either strength appearing as a rising force, or instability by giving the impression of a falling pillar.

Stylistically, the sculpture is executed in the Minimalist style that would dominate Kadishman's art in the late 1960s. Initially, he sketched the sculpture in 1963, before making a small granite model the following year. He also created a large-scale version painted in yellow for the High Park in Toronto. In the case of The Three Discs (Uprise), the artist purposefully wanted the steel to rust and erode overtime and under shifting weather conditions. Though sharing certain similarities in form, Three Discs differed from the steel Minimalist sculptures of Kadishman's contemporary, American Richard Serra, who was (at this point in his career) concerned primarily with creating works that would create both a visual and (meta)physical effect on the viewer.

Because the sculpture is in close vicinity to several key cultural institutions (Habima Theater, the Fredric R. Mann Auditorium, and the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion for Contemporary Art), it is often interpreted as a symbol of human creativity; the upward trajectory of the sculpture signifying the breakthrough of the human spirit. On the negative side, the sculpture has been read rather as a statement on the economic instability and high inflation that was rampant in Israel at the time of its construction. In 2015, the sculpture was the subject of national headlines when the mayor of Tel Aviv decided to utilize it as part of a campaign to raise awareness for breast cancer by placing a giant pink bra on two of the discs. The well-intentioned stunt backfired and drew criticism from the artistic community who deemed the intervention unbecoming of such an iconic national monument.

Corten Steel - Habima Square, Tel Aviv

Untitled

In the early 1970s, Kadishman turned away from Minimalism towards Conceptual Art. During this period, he created a series using phonebook pages as a basis for his drawings. Since he collected the pages from phonebooks found in American hotel rooms during his travels, Kadishman referred to the series as his "travel diary" or "the book of hotels I stayed at". In this instance, he crossed out the names and phone numbers from the page to evoke feelings of alienation and melancholy that captured his experiences of modern living.

Art historian Omer Mordecai noted the similarity between the series and the works of Franz Kline who created Abstract Expressionist drawings on phonebook pages in the 1950s. While both artists were drawn to the untraditional material, their motivations differed significantly. Kline was mainly interested in the aesthetic qualities of the page and used the material to further experiment with abstract forms. Kadishman, rather, chose the typographic backdrop to create imagery that reflected the human condition as experienced in the New York's urban environment.

The series should also be viewed in the context of new developments in Conceptual Art. Curator and critic Dalia Manor specified that means of communication were a major focus of Conceptual Art, as both subject and medium: "at that period, art by means of the mail, and works drawing inspiration from the telephone, were fashionable". Kadishman made his unique contribution to the trend, and later utilized the phonebook pages as the basis for a series of prints.

Pencil on a phonebook page - Private Collection, New York

The Sacrifice of Isaac

This monumental sculpture, located in the square of the Tel Aviv Museum, represents the artist's interpretation of the biblical story of the binding of Isaac. In the biblical narrative, God tested Abraham's faith by commanding him to sacrifice his son Isaac. Because Abraham obeyed, God sent a messenger to spare Isaac, and sacrificed a ram in his place. With his sculpture, Kadishman transformed the fundamental narrative of the biblical narrative. The sculpture consists of three elements: Isaac, the ram, and the mourning women. The character of Isaac is rendered to a flat face on the floor, with simple childlike features. On the left, the tall and imposing ram stands over Isaac, while the mourning women on the right look toward the scene, frozen in a state of pain. In Kadishman's version, there is no salvation for Isaac, who is ultimately killed by the ram. The artist excluded Abraham from the composition, eliminating the possibility of divine intervention or protection for Isaac.

Kadishman subverted the biblical myth to comment on the political and social realities of Israeli life, a country plagued by war and conflict since its inception. The sacrifice of Isaac represents the sacrifice of fathers and mothers who send their sons to war for the good of the nation. Isaac thus becomes a symbol for young soldiers in battle, for victims of war who die meaningless and random deaths. Moreover, Kadishman added the figures of the mourning women, a female presence that is absent from the biblical story. She emphasizes pain and sadness, and signifies the importance of women speaking out on subjects like politics and nationalism. Rather than including only Sarah, Isaac's mother, Kadishman presents two women, possibly as a way of representing both sides of the conflict and united by their common grief.

The Sacrifice of Isaac has a strong connection to the artist's personal biography. He developed the concept after his son Ben was drafted to the Israeli army. The artist reflected on his son's new status, his own past as a soldier, and that of his father before him. For Kadishman, sacrifice is a cycle of Israeli life, required of each generation in its defense of the nation state. Confronting this reality, Kadishman's art rejects the vicious cycle that perpetuates pain, sadness and grief: "I do not recall my life and country without war. But I am allowed to dream of it ... People make for themselves the rules by which they live - or die ... An eighteen-year-old does not send himself to war".

Corten steel - Tel Aviv Museum

Motherland

In the later phases of his career, the donkey became a central motif in Kadishman's art. Cut out of a steel sheet, this singular sculptural unit depicts the silhouette of a donkey in profile. The donkey's stomach is hollow, creating a compartment for a landscape scene. As the title suggests, Kadishman associated the animal with his homeland (of Israel). In this context, the landscape in the donkey's belly can be emblematic of a nostalgic past, specifically the early Zionist efforts that developed an agricultural society in the Jewish settlement. The sculpture points to the demise of this structure: the donkey is no longer a part of this idyllic landscape, instead it only projects the landscape as a remnant of the past. In this way, the artist also acknowledges the tumultuous history of violent conflict that was part and parcel of Israeli life.

Traditionally, the donkey is a beast of burden, an animal used to cultivate the soil and transport goods. Curator Gabriele Holthuis elaborated on the significance of the donkey in Kadishman's art: "the donkey acquires the role of a peaceful companion ... It is neither victim nor perpetrator, but a quiet observer, who bears in itself all the good and all the evil of this world". The sculpture represents the donkey as a vessel for the past, while the belly serves as a kind of mirror, projecting dreams and memories. At the same time, the donkey can also hold a message of optimism. In traditional Jewish iconography, the Messiah would arrive at the Gates of Jerusalem on a white donkey. But his version of messianism does not aspire for the reestablishment of an ancient Jewish kingdom, but rather a plea for peace and coexistence in his motherland.

Corten Steel - Israel Museum, Jerusalem

The Herd

Although Kadishman was first acclaimed as a sculptor, he become recognized more as a painter in the later phases of his career. Since the early 1980s, Kadishman painted several thousand sheep head portraits, which have become his trademark. For the artist, his sheep paintings function like traditional portraits: every sheep has its unique traits, and no two sheep are exactly alike.

With The Herd he selected five hundred of these paintings and arranged them in a way that mimics a herd or flock of sheep. Each canvas was mounted on two wooden squares and positioned upright on the ground. Painted in a Neo-Expressionist style, Kadishman presented a variety of portraits, ranging from monochromatic to brightly colored; from naturalistic to semiabstract images. Since Kadishman often identified the sheep as a symbol of innocence and sacrifice, some of the paintings were matched with drawings of sacrificial scenes. The audience experienced The Herd by roaming freely through the group of paintings. In this manner, the viewer can closely examine the animals: some timid, others more aggressive or just curious. When one walks through the paintings, they may also notice the backs of the canvases; plain brown surfaces that stand in contrast to the expressive portraits.

The art historian Ulrich Schneider interpreted The Herd as a metaphor for life. According to Schneider, the exposed backs of the canvases allude to gravestones, a reminder of the inevitable end of life. In 1996, the artist installed a version of The Herd in a meadow near the Ben Shemen Forest in Israel, creating a synthesis between art and nature. The canvases trembled in the blowing wind, and at times it appeared as if the sheep were grazing or lying down in the grass. Some of the paintings toppled over, giving the impression of fallen gravestones. On another occasion, the paintings were installed at a local cemetery, leaning against the tombstones. In the somber setting, the paintings evoked an atmosphere of sad peacefulness. In The Herd, Kadishman expressed the range of emotions that embody the human experience, while at the same time hinting at the fragile nature of life itself.

Installation, acrylic on canvas - Ben Shemen forest, Israel / Jaffa, Israel

Shalechet (Fallen Leaves)

Located in the Jewish Museum in Berlin, the installation consists of over 10,000 iron faces strewn across the hall. The iron discs are individually-cut, screaming faces, some reminiscent of the face in Edvard Munch's The Scream (1893). The audience is prompted to walk on the anonymous faces while hearing the metal crack under their feet. The sound of metal-on-metal reverberates in the space recalling sounds of forced labor or of trains arriving at a concentration camp.

Although the work is primarily associated with the Shoah (the Holocaust), it holds a universal message against violence and human suffering. Kadishman himself notes that the work can relate to different tragedies such as World War I and Hiroshima. In part, Shalechet derives its meaning from the context of its presentation. For example, it took on a new meaning in 2018, when it was exhibited at the Memorial Hall dedicated to the victims of the Nanjing massacre in China.

The name "Shalechet" ("Fallen Leaves" in English) comes from the poem "Soldiers", written in the trenches of World War I by Italian poet Giuseppe Ungaretti: "We are like leaves on the trees in autumn". Much like the turning leaves, the faces in the installation also change overtime: they are altered by rust and debris, and the molten metal hardens on the edges and inner spaces of the facial features. The leaf represents the cyclic transformation in nature, that can be compared to the different stages of life. In Shalechet, Kadishman provokes a potent experience to instill his humanist message, one that acknowledges collective human suffering and hopes for a new life in the spring.

Installation - Jewish Museum, Berlin

Biography of Menashe Kadishman

Childhood

Born in Tel Aviv during the British Mandate of Palestine, Menashe Kadishman was the son of two Zionist (supporters of the state of Israel as the Jewish homeland), Bilha and Ben-Zion Kadishman. His father, who immigrated from Ukraine in the 1920s, was a member of the Jewish militia (and later the national army of Israel) and Kadishman was raised in the Zionist spirit of the growing Jewish settlement. At the same time, his home environment fostered creativity: his mother painted, and his father dabbled with sculpture.

At the age of 15 Kadishman lost his father and began working to help support his family. Despite these early familial commitments, Kadishman found time to study painting under Aharon Avni. He then studied under painter and sculptor, and founder of the modernist art group "New Horizons", Moshe Sternschuss, and later with sculptor, printmaker, and wood carver, Rudi Lehmann who was known nationally for his representation of animals.

Early Training and Work

In 1950, Kadishman joined the Nahal infantry brigade, a division of the Israeli Defense Force that combined military service with the building of agricultural settlements. As part of his service, he worked for several years as a shepherd in Kibbutz Maayan Baruch and Kibbutz Yizre'el, both on Israel's northern border with Lebanon and Syria. Working as a shepherd, Kadishman came to appreciate the unique characteristics of the local landscape while his time spent living with the herds left such an impact on him it would shape his artistic vision.

By the end of the 1950s, Kadishman decided to complete his training abroad. His chosen destination was England, the home of sculptor Henry Moore, perhaps his greatest influences. On the advice of friend and artist Buky Schwartz, Kadishman enrolled at London's St Martin's School of Arts where he studied between 1959-61. There, he came under the influence of Anthony Caro, leader of the so-called New Generation of British sculptors. As the Israeli author and scholar Gideon Ofrat wrote, Kadishman "began his journey as a sculptor at the end of the 1950s with rough stone sculptures of "altars" [which were] inspired by his work on the archaeological excavations at Tel-Hazor in the Galilee [and] fashioned the altar through the abstract-geometric language he absorbed in the classes of Anthony Caro". In 1962 Kadishman moved to the Slade School of Art, where he was taught by a second prominent English sculptor, Reg Butler.

Although Kadishman was respected and admired by his peers, he struggled as a foreign artist in Britain. Without a British passport, he was not eligible for many official exhibitions, and often felt alienated within his own artistic circles. Still, he gradually built his reputation, and in 1965 held his first solo show at the Grosvenor Gallery in London. As art critic Dalia Manor noted, the curator of the Grosvenor Gallery "Charles S Spencer preferred to link his work to the artist's native land, Israel 'with its harsh, linear landscape, vast deserts (sic!), bare mountain ranges' and to his 'Hebraic attitude'". While in London, Kadishman met Tamara Alferoff, a British psychoanalyst. The pair married in 1965, and subsequently had two children, Ben and Maya. In 1967 Kadishman gained international recognition when he won the first prize for sculpture at the 5th Paris Biennale for young artists and in 1968 when he participated in Documenta 4 in Kassel, Germany.

Kadishman's sixties sculptures were Minimalist in style. They were large structures, composed of geometrical shapes, that appeared to defy gravity. He also gained recognition for combining unexpected materials such as metal and glass in sculptures such as Segments (1969).

Mature Period

At the turn of the 1960s - 1970s, Kadishman travelled to South and North America where he explored the relationship between art and nature. He first worked with trees during the international Sculpture Symposium in Montevideo. The setting was a forest, which led the artist to reassess his whole approach to art. Instead of using the sculpture he had brought to the site, Kadishman nailed yellow steel plates to the forest trees, creating a contrast between the organic and the industrial: "I wanted to work with the forest God had created, the organic forest, and to fit into it a mechanical forest, a man-made forest containing forms that would be a contrast to nature", he said. He was to further develop this Land Art experiment during his stay in New York.

By the time he arrived in New York he was recognized as a rising figure within Land Art movement, and he made friends of Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and Christo. As art historian Amnon Barzel says of his Central Park, New York: "The organic forms, the eucalyptus trees and the man-made angular technological forms, intermingled to define 'an artistic space' within the given space of nature. The straight-angled metal plates painted in industrially pigmented yellow seemed as if they had come out of a Mondrian painting in order to hover in three dimensions within the colors of nature".

In 1972, with his international standing on the rise, Kadishman unexpectedly decided to return to Israel (prompted perhaps by the breakdown of his marriage). During this period, he focused on monumental sculpture and public art, which allowed him to explore his fascination more fully with art and nature. He first developed an environmental series called The Forest through which he produced different sculptures of trees and tree silhouettes.

In the mid-1970s he produced his Suspended sculptures. These massive steel-wrapped structures were placed on adjacent hilltops. With no visible evidence of how the "floating" sculptures were made, Kadishman was encouraging his viewer to contemplate the relationship between engineering and nature and what natural forces might exist directly beneath the earth's surface.

In 1978, Kadishman represented Israel at the Venice Biennale, with the exhibition Sheep Project: Nature as Art and Art as Nature. Inspired by his days as a shepherd, Kadishman mediated between art and nature, acting as an artist-cum-shepherd. The Israeli Pavilion was transformed into a wooden pen populated by a flock of live sheep (that Kadishman bought in an Italian town north of Venice). He marked the sheep with patches of blue color like those used to mark ownership. By roaming around the pen, the sheep transformed into "living art", as the blue spots formed different abstract shapes. Kadishman said that he wanted his audience to feel the "visceral" experience of nature: "I want my work to exercise all the senses. Even those abandoned by art. Smell, sounds, touch. Now, in Venice, in the pavilion populated with sheep that move, chew and dung - the spectator exercises all his senses, because I demonstrate a segment of real life".

The Biennale was a pivotal event in Kadishman's artistic development, leading him to explore new mediums and themes. And the documentary photographs from his performance in Venice inspired him to experiment with color. Initially, Kadishman painted on the photographs to create prints, before transitioning to painting portraits of sheep. His sheep paintings came in many variations: sheep heads reminiscent of traditional portraits, sheep heads inspired by Andy Warhol's Pop Art portraits, large compositions of herds and paintings of shepherds tending to sheep. The sheep will become his ultimate trademark, reproduced in endless variations in both sculpture and painting. At the same time, he was criticized for using sheep as a kind of gimmick. Kadishman rejected this accusation claiming that painting sheep was a liberating experience, and the sheep was a symbol of great personal significance to him.

A decade after his return to Israel, Kadishman experienced a profound personal crisis. In 1982 he lost his beloved mother Bilha, underwent major stomach surgery, and witnessed the breakout of the First Lebanon War with his son, Ben, enlisted to the Israeli Defense Forces. Grappling with his personal difficulties, and the political reality of life at home, Kadishman began to frame the history of Israel around the concept of sacrifice (although thankfully Ben returned home unharmed). This process of self-reflection resulted in a series of works dedicated to the biblical story of the Binding of Isaac. According to the narative, God tested Abraham's faith by commanding him to sacrifice his beloved son Isaac. Because Abraham obeyed, Isaac was spared, and a ram was sacrificed in his place.

Kadishman personally related to the story and identified with the character of Abraham by equating the biblical sacrifice with the sacrifice of sending his own son to war: "The sacrifice of Isaac is not an abstract symbol for me. It is a part and parcel of my own biography and that of my generation, and it may be the biography of my children after me". Kadishman transformed the epic story by viewing it in secular terms, in his version Isaac is not spared and the ram remains a victorious and imposing presence. He initially developed his conception through drawings and paintings, before moving to monumental sculptures. Some versions of the sacrifice included the sheep, which the artist "connected metaphorically to soldiers who fell in wars".

Towards the end of the 1980s, Kadishman produced his Birth series. The series introduced the figure of the "Great Mother"; a woman who comes to symbolize the giving and taking of life and the universal principle of sacrifice. As Kadishman's website describes it: "In his unique treatment of this subject, the artist accords Sarah [Abraham's wife and mother of Isaac], a role of no less importance than of the father Abraham in the intended sacrifice of the son, Isaac. Sarah becomes a modem image of the mother of the fallen Israeli soldier - of all soldiers in all Wars". Similar themes of sacrifice are addressed in works like Pieta (1985), where the protagonist finds no salvation, and Prometheus (1986-87), which questions the value of heroic sacrifice altogether. At the center of all these artworks is Kadishman's humanist message. It is true that his work is centered around the Israeli experience, but it still relates to broader concepts of human existence and the self-destructive tendencies of humankind in general.

Late Period

In 1990 Kadishman received the highest national honor when he was awarded Israel's Dizengoff Prize for sculpture. As he moved into the period of his late career, he continued with some of his existing preoccupations while also expanding his repertoire. Other animals (apart from sheep) like birds, horses and donkeys became a part of his visual lexicon. Meanwhile, one of his most ambitious and well-known projects was the Shoah memorial installation Shalechet (Fallen Leaves) (1997-2001) which was housed at the Jewish Berlin Museum. Artistically, Kadishman also remained true to his fascination with nature and the local environment.

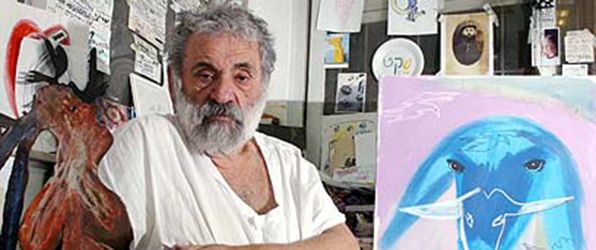

Over the years, the artistic community and the public came to know Kadishman as a vibrant, inviting, and generous individual. His studio in Tel Aviv was always welcoming of colleagues, family, and friends who would often drop by to chat and watch the artist at work. He remained prolific up until his death. Kadishman passed away on May 8, 2015 and was buried in the Kiryat Shaul cemetery in northern Tel-Aviv.

The Legacy of Menashe Kadishman

With artists Reuven Rubin and Mordecai Ardon, Kadishman ranks as one of Israel's greatest artistic pioneers. He has left a rich and diverse body of work that includes thousands of sculptures, paintings, and drawings, not to mention dozens of illustrated books. Kadishman's most important art is concerned with the natural and urban landscape and the idea of the collective memories and histories of the people of Israel. Several museums, universities, hospitals, parks, and streets throughout the country are adorned with Kadishman's work. The potency of his art was underlined when a newly installed sculpture, Birth (1990), placed in Ramat Gan National Park, was the center of a 2016 national news story when young orthodox women flocked to the sculpture believing it had the power to bestow fertility.

But although he was widely adored by the Israeli public and the Tel Aviv art establishment, Kadishman conceded in an interview with The Forward magazine that his move back to Israel (from New York) probably limited the reach of his fame. He said: "My mistake, if you can call it that, was to come back to Israel. It was [American sculptor] George Segal who told me if I had stayed in New York, I could have become one of the great American artists [but] I really have nothing to kvetch about. When I lived in Chelsea [in the 1970s], I would walk down 23rd Street and maybe get a nod or two. But here in Israel, when I stroll down Dizengoff Street [in Tel Aviv], I'm treated just like an Old Master". One might add that in the gift shops and galleries of Israel, tourists from around the world can take home a piece of Kadishman's art with his colorful sheep reproduced on everything from posters to calendars, to mugs, to computer mousepads.

Influences and Connections

-

![Henry Moore]() Henry Moore

Henry Moore -

![Anthony Caro]() Anthony Caro

Anthony Caro - Yitzhak Danziger

- Reg Butler

-

![George Segal]() George Segal

George Segal -

![Robert Rauschenberg]() Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg -

![Andy Warhol]() Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol - Isaac Witkin

- Dani Karavan

-

![Minimalism]() Minimalism

Minimalism -

![Conceptual Art]() Conceptual Art

Conceptual Art -

![Land Art]() Land Art

Land Art - New Generation Sculpture

- Hanna Sahar

- Lucas Shauvet

-

![George Segal]() George Segal

George Segal -

![Robert Rauschenberg]() Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg -

![Andy Warhol]() Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol - Isaac Witkin

- Dani Karavan

-

![Minimalism]() Minimalism

Minimalism -

![Conceptual Art]() Conceptual Art

Conceptual Art -

![Land Art]() Land Art

Land Art - New Generation Sculpture

Useful Resources on Menashe Kadishman

- Menashe KadishmanOur PickBy Jacob Baal-Teshuva

- Kadishman (1996) (in Hebrew)By Pierre Rastani

- Menashe Kadishman (1999)By Omer Mordechai and Arturo Schwarz

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI