Summary of Gustav Klimt

Austrian painter Gustav Klimt had many quirks. Once, his patron Friederika Maria Beer-Monti came to his studio to have her portrait painted, wearing a flashy polecat jacket designed by Klimt's friends at the Wiener Werkstätte. One would think Klimt would approve, but instead he had her turn it inside out to expose the red silk lining, and that was how he painted her. But Klimt, Vienna's most renowned artist of the era, had the prestige to do this. He is still remembered as one of the greatest decorative painters of the 20th century, while also producing one of the century's most significant bodies of erotic art. Initially successful in his endeavors for architectural commissions in an academic manner, his encounter with more modern trends in European art encouraged him to develop his own highly personal, eclectic, and often fantastic style. As the co-founder and first president of the Vienna Secession, Klimt also ensured that this movement would become widely influential. Klimt never courted scandal, but the highly controversial subject matter of his work in a traditionally very conservative artistic center dogged his career. Although he never married, Klimt remains romantically linked to several mistresses, with whom he is said to have fathered fourteen children, despite his extreme discretion about his personal life.

Accomplishments

- Klimt first achieved acclaim as a decorative painter of historical scenes and figures through his many commissions to embellish public buildings. He continued to refine the decorative qualities so that the flattened, shimmering patterns of his nearly-abstract compositions, what is now known as his "Golden Phase" works, ultimately became the real subjects of his paintings.

- Though a "fine art" painter, Klimt was an outstanding exponent of the equality between the fine and decorative arts. Having achieved some of his early success by painting within a greater architectural framework, he accepted many of his best-known commissions that were designed to complement other elements of a complete interior, thereby creating a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Later in his career, he worked in concert with artists of the Wiener Werkstätte, the Austrian design organization that aimed to improve the quality and visual appeal of everyday objects.

- Klimt was one of the most important founders of the Vienna Secession in 1897, and served as its initial president, though he was chosen less for his completed oeuvre - relatively small at that point - than his youthful personality and willingness to challenge authority. His forcefulness and international fame as the most famous Art Nouveau painter contributed much to the Secession's early success - but also the movement's swift fall from prominence when he left it in 1905.

- Although Klimt's art is now widely popular, it was neglected for much of the 20th century. His works for public spaces provoked a storm of opposition in his own day, facing charges of obscenity due to their erotic content, eventually causing Klimt to withdraw from government commissions altogether. His drawings are no less provocative and give full expression to his considerable sexual appetite.

- Despite his fame and generosity in mentoring younger artists, including Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, Klimt produced virtually no direct followers and his work has consistently been regarded as highly personal and singular, even up to the present day. However, his paintings share many formal and thematic characteristics with the Expressionists and Surrealists of the interwar years, even though many of them may not have been familiar with Klimt's art.

The Life of Gustav Klimt

Proudly acclaiming, ”There is no self-portrait of me,” Klimt found his means of expression not in projecting his own image, but in the erotic power of his sensual nudes, his femme fatales. He was, he said, more interested in “painting.. other people, above all women.”

Important Art by Gustav Klimt

The Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater

This was an important commission for Klimt's early career: the Vienna city council asked Klimt and his partner Franz Matsch to paint images of the old Burgtheater, the city's opera house - built in 1741 and slated for demolition after its replacement was finished in 1888 - as a record of the theater's existence. Unlike Matsch's counterpart to this picture, which shows the stage of the Burgtheater from a seat in the auditorium, Klimt's treatment does the exact opposite - a strange choice, but one that is quite significant architecturally, as it shows the full arrangements of loges and auditorium floor seats along with the ceiling decoration. It is typical of the academic style of Klimt's early work, and of the influence on him of Hans Makart.

When word of this commission was leaked to the public, many people begged Klimt to insert their portraits, however small, into the picture through special sittings with the artist, as being immortalized on canvas as a regular attendee at the Burgtheater constituted a tangible emblem of one's social status. As a result, the painting serves not only as a valuable record of the theater's architecture, but also essentially as a catalog of the city's political, cultural, and economic elites - over 150 individuals in all. Among the audience members are Austria's Prime Minister; Vienna's Mayor; the surgeon Theodor Billroth; the composer Johannes Brahms; and the Emperor's mistress, the actress Katherina Schratt. Though the subject is appropriate for a history painting, its dimensions (the width, its longest side, measures less than 37 inches) are diminutive, making the precision of Klimt's individual portraits all the more impressive. Critics at the time agreed, as Klimt was awarded the coveted Emperor's Prize in 1890 for this painting, which significantly raised his profile within the Viennese art community, and a flurry of other important public commissions for buildings on the Ringstrasse soon followed.

Gouache on paper - The Historical Museum of Vienna

Pallas Athene

Though the Secessionists were known as a group that attempted to break with artistic traditions, their relationship with the past was more complex than a simple forward-looking mentality. Klimt, along with many of his fellow painters and graphic artists, cultivated a keen understanding of the symbolic nature of mythical and allegorical figures and narratives from Greece, Rome, and other ancient civilizations. With his soft colors and uncertain boundaries between elements, Klimt begins the dissolution of the figural in the direction of abstraction, that would come to full force in the years after he left the Secession. This painting exudes thus a sensory conception of the imperial, powerful presence of the Greco-Roman goddess of wisdom, Athena, and the inability of humans to full grasp that, rather than a crisp, detailed visual summation of her persona.

Also significantly, the hazy quality of the image allows Klimt to emphasize the goddess' androgynous character, a blurring of gender identity that was featured in ancient descriptions and depictions of her, and explored by many other artists and cultural luminaries at the turn of the century. She is dressed in the military regalia that traditionally identifies her as a warrior and the protector of her eponymous city, Athens - qualities normally associated with masculinity. Only the strands of hair that thinly drape down from each side of her neck (and almost blend with the golden color of her helmet and breastplate) give a hint as to her femininity. Barely visible at the left side of the painting, she holds the nude figure of Nike, representing victory, arguably the only clear feminine reference in the work.

The haziness evokes the contemporaneous exploration of dreams by Sigmund Freud, whose seminal work on the subject would be published in Vienna just two years later. It is tempting to read Klimt's painting in the context of Freud's view of dreams as the fulfillment of wishes, which might suggest that the powerful, imperious woman is the object of male desire, but also potentially that the traditional feminine persona must be costumed in order to attain such powerful status.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Wien Museum, Vienna

Medicine

In 1894, Klimt was commissioned by the Ministry of Culture to provide paintings for the new Great Hall of the University of Vienna, recently constructed on the Ringstrasse. Klimt's job was to paint three monumental canvases concerning the themes of Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence, respectively. By the time Klimt began painting the canvases four years later, however, he had joined the Secession and abandoned the naturalism of the Old Burgtheater to challenge the conventional subject matter. The overarching theme that was supposed to unify the three University paintings was "the triumph of light over darkness," within which Klimt was granted a free hand. None of the finished products, however, conveys this theme with any degree of clarity. Medicine, the second of the three to be unveiled, was the canvas that caused the most controversy.

This detail from Medicine shows the figure of Hygeia, the mythological daughter of the god of medicine, who was located at the bottom center of the canvas and identified by an accompanying snake and the cup of Lethe. Above Hygeia rose a tall column of light, to the right of which rose a web of nude figures intertwined with the skeleton of Death. To the other side of the light column floated a nude female whose pelvis was thrust forward, while below her feet floated an infant (to whom she might have just given birth) wrapped in a swath of tulle. The imagery provoked a storm of criticism on two levels. First, faculty and Ministry officials charged that it was pornographic, particularly the female with the thrusting pelvis - thereby demonstrating the stodginess of Vienna's cultural community. Second - perhaps a more valid argument - the painting did nothing to illustrate the themes of medicine, either as a preventative or healing tool. The acrimonious response to Klimt's works eventually prompted him, in 1905, to buy back the three works for 30,000 crowns with the help of his patron August Lederer, who received Philosophy in return.

Klimt's work proves difficult to decipher, and it appears that one of his goals with the painting was to show the ambiguity of human life, simultaneously representing the themes of birth and death. In some ways, it proves highly ironic, as Vienna at the time was one of the major centers of medical research: along with Sigmund Freud, who had just published The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), it was home to the pioneering abdominal surgeon Theodor Billroth. In this respect, Medicine demonstrates how, despite the great inroads the Secession had made in the four years since its founding, the movement had not decisively overturned conservative attitudes towards modern art in Vienna. For Klimt, the entire affair represented an ultimate public humiliation and rejection; he did not exhibit in Vienna for five years after 1903, and he swore off official commissions and withdrew to take on only private portrait commissions or landscapes for the remainder of his career. His trio of University paintings, born into a firestorm of controversy, met their own fiery fate as they found their way into the collections of Jews and became three of Klimt's many works confiscated by the Nazis. They were incinerated in May 1945 inside the Schloss Immendorf, the lower Austrian castle where they had been stored, by retreating SS troops.

Oil on canvas - Destroyed in 1945

The Beethoven Frieze

The Beethoven Frieze, only a detail of which is shown here, was painted by Klimt for the 14th Secession exhibition in 1902 - arguably the group's most famous - dedicated to the eponymous German composer who was a longtime Vienna resident. It is a monumental work, measuring some 7 feet tall by 112 feet long, and weighing 4 tons. Painted on the interior walls of the Secession Building, it was preserved but was not displayed again until 1986; it is now permanently on view in the basement.

The Beethoven Frieze forms part of the exhibition-as-Gesamtkustwerk, or total artistic environment that the Secessionists sought to create. For them, this often included all branches of the arts - not simply the visual arts, but also the performing arts, such as symphonic works, theater, and opera; accordingly, the contemporary Viennese composer Gustav Mahler's adaptation of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony was playing at the opening of this exhibition of the Secession. The Gesamtkunstwerk is underscored by details such as the incorporation of gems into the painted surfaces to add to the shimmering effects.

The frieze's narrative tracks the narrative of three female figures, called Genii, that represent humanity seeking fulfillment. They rely on a gigantic knight in shining armor - said to be representative of a great leader for the German-speaking countries of Europe - to lead them through a harrowing minefield of characters whose elongated and exaggerated forms at once reference the Gorgons like Medusa from Greek mythology and represent disaster and vices such as sickness, madness, death, intemperance, and wantonness. Fulfillment does come at the end, represented by a pair of nude female and male figures locked in an almost erotic embrace in a golden aura, surrounded by a choir, a reference to the choral performance of Schiller's poem "Ode to Joy" at the end of the Ninth Symphony.

Despite the modern notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the reliance on very old tropes - not only figures from Greek mythology but the flattened depictions of figures like those seen on ancient Greek vases - demonstrate the range of influences on the Secessionists. It also suggests their desire to synthesize a contemporary art from old and new, innovation and tradition, which would respond to the hopes and desires of turn-of-the century society.

Casein paint on stucco, inlaid with various materials - The Secession Building, Vienna

Adele Bloch-Bauer I

This work, considered by many to be Klimt's finest, may also be his most famous due to its central role in one of the most notorious cases of Nazi art theft. Of all the many women Klimt painted from life, Adele Bloch-Bauer, the wife of the Viennese banker and sugar magnate Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, was one of his favorites, sitting for two portraits and serving as the model for several other paintings, including his famous Judith I (1901). Though Klimt was rumored to be romantically involved with numerous women he painted, his extreme discretion means there is still no consensus amongst scholars as to the exact nature of his and Adele Bloch-Bauer's relationship.

The painting is principally concerned with the dissolution of the real into pure abstract form. Though Klimt depicts Bloch-Bauer as seated, it is nearly impossible to discern the form of the chair or to separate the forms of her clothing from the background. Klimt was largely unconcerned at this time with depicting his sitter's character, and even less so with providing location and context, omissions that were common in all of Klimt's earlier portraits. Klimt's biographer, Frank Whitford, has described the picture as "the most elaborate example of the tyranny of the decorative" in the artist's work. The use of gold and silver leaf underscores the precious nature of the jewels Bloch-Bauer is wearing, as well as the depths of the love for her felt by Ferdinand, who commissioned the painting. It places the work squarely within Klimt's "Golden Phase" from the first decade of the 20th century, wherein he used dozens of gold patterns and shades of the metal in his paintings to create these glittering effects. Not surprisingly, when the Osterreichische Galerie Belvedere received the painting, it was retitled The Lady in Gold, the name by which it is still sometimes known today.

Despite his move towards modern abstraction, Klimt's work nonetheless draws on several older sources. Most prominent are the Byzantine mosaics of the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, which Klimt visited in December 1903. Many of these mosaics use a similar flat gold background, and depict the bejeweled Byzantine empress Theodora; Klimt's depiction of the choker worn by Adele Bloch-Bauer in this portrait is modeled on these mosaics. Art historians also trace the eye-like imagery in Bloch-Bauer's dress to Egyptian motifs, while the whorls and coils and other decorative devices based on Bloch-Bauer's initials arguably resemble designs from ancient Mycenae and classical Greece.

Adele died in 1925. As the Bloch-Bauers were Jewish, Ferdinand's assets became targets of Nazi plunder after the annexations of Austria and western Czechoslovakia in 1938, and Ferdinand ultimately fled to Switzerland. The Nazis installed the painting in the Austrian Galerie Belvedere, which renamed it and eventually took the position that no art theft had taken place. Ferdinand died in 1946, but not before willing his confiscated paintings (including Bloch-Bauer I and five other Klimt works) to his nephew and two nieces. These included Maria Altmann, who in 2000 filed a lawsuit to recover the paintings. The high-profile case, which came before the United States Supreme Court, was ultimately successful and the paintings were returned to the Bloch-Bauer family in 2006. That June Altmann sold Bloch-Bauer I to American collector and cosmetics magnate Ronald S. Lauder for $135 million, at the time a record price paid for any painting. Lauder gave Bloch-Bauer I to the Neue Galerie for German and Austrian art in New York, which he founded, where it hangs on permanent display today. It remains probably the most famous example of Nazi art theft, having been the subject of numerous articles, books, and films.

Oil, gold and silver leaf on canvas - Neue Galerie, New York City

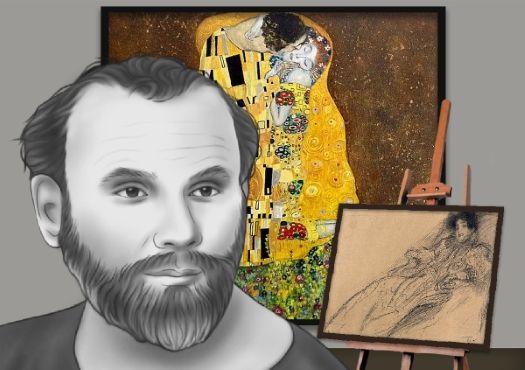

The Kiss

The Kiss is perhaps Klimt's most popular and clear celebration of sexual love, and probably his most reproduced work. Like Bloch-Bauer I, it is one of the key constituent paintings of Klimt's "Golden Phase" lasting roughly from 1903-09, and is often considered a prime example of Art Nouveau painting. It demonstrates Klimt's ability to synthesize a work while drawing on an extraordinary range of sources, even though the overall composition remains fairly straightforward.

Klimt's subject matter is simple, depicting a couple locked in an intimate embrace on the edge of a meadow, indicated by the luminous, almost quilt-like pattern of flowers that extends beneath them. The composition's construction suggests a high degree of familiarity with the Arts and Crafts movement. The flattened patterning of the meadow and the clothing of the figures, for example, resemble the fabrics produced by William Morris in the late-19th century. Klimt's use of fine materials, particularly gold and silver leaf, help highlight the precious nature of the work and point to a high degree of specialized craftsmanship for their use on canvas; their presence here also recalls the combination of colored and gold paint used in medieval colophons and other illuminated manuscripts - sources that also inspired Morris in creating the Kelmscott Press.

With Klimt, however, the source material becomes much more complex. We can trace the use of gold to his affinity for Byzantine art, such as the gold fields for the mosaics he had seen in Ravenna in 1903. And while Morris and medieval sources used such precious materials to exalt textual subject matter - either the word of God or great literature - Klimt uses them to highlight the sacred nature of human relationships and the bond between sensual lovers, a key theme undergirding much of Art Nouveau. The link with Art Nouveau is further underscored by Klimt's exaggeration of the figures, as well as the way that he seems to meld their forms together despite the square-circle/male-female dichotomy. Finally, the confinement of the figures to the central strip of the canvas, with their heads nearly touching the top border, recall techniques used in vertical Japanese pillar wood-block prints, which Klimt avidly collected.

Given Klimt's studies for this work that depict the male figure with a beard, it is tempting to read the kiss as autobiographical, with the painter as the man and Emilie Flöge or Adele Bloch-Bauer possibly serving as the model for the woman, though this remains purely speculation. By leaving the identity of the figures as ambiguous, Klimt allows the image of The Kiss to embody a universal, timeless vision of romantic love, rather than merely a personal and situational significance, thereby broadening its appeal.

Oil, gold and silver leaf on canvas - Osterreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna

The Park

Beginning just after the turn of the century, Klimt turned to landscape painting as another genre of interest, one which would occupy him for the last fifteen years of his career. Though his landscapes such as this one suggest that Pointillism exerted a great influence on him, Klimt never expressed an interest in utilizing optics in his work, and the formal aspects of The Park seem to bear this out. Klimt does not use diametrically-opposed dots of color to increase the luminance of the greens, yellows, or blues present in the trees' leaves, for example. Rather, the top nine-tenths of the square painting appear as a massive textured abstract patchwork or decorative mosaic. Only with the aid of the work's lower section does their representational function become evident.

Klimt's manipulation of space becomes a central strategy for this work, as the seemingly solid, unbroken mass of foliage visually dominates the canvas and seems even to be pressing down on the space underneath it, including the tree trunks (those in the foreground almost appear as if they are being squashed), and the metal bench at the bottom right appears as if it will soon be swallowed by the descending curtain of leaves. Despite the function of the bench as a location for humans to rest while ostensibly enjoying the natural surroundings, here the bench welcomes no sitters, whose heads might be otherwise crushed or lost in the tangle of foliage. In this respect, therefore, Klimt is arguably drawing on the Romantic tradition of the sublime, with its exposure of the awesome power of nature, a theme that had been powerfully explored a century before by German painter Caspar David Friedrich, who, like Klimt, cultivated a solitary professional existence as a difficult artist to approach and understand. Thus, while cognizant of the developments of modern life in the transformations of the city around him, Klimt in The Park acknowledges man's continued inability to fully tame nature and bend it to his wishes.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Nude Figure

Like most visual artists, Klimt produced hundreds of drawings and sketches during his lifetime, many in preparation for larger works. He was the embodiment of the stereotypical male artist whose studio was also the location for his liaisons with many of his nude female models - a pattern of behavior that, unfortunately, has a lineage that extends back long before Klimt's era and forward to the present day. Klimt was charming, and with the various women he had relationships with he fathered some fourteen children - possibly more. He was also a great admirer of the female body, and sketches of women, particularly nude models, make up a large percentage of his surviving graphic work. It was here that Klimt probed the most erotic portions of his brain, even more so than his paintings, which often are rather tame by comparison. Many of his drawings of women are extremely explicit sexually - sometimes too much so to be shown in museum exhibitions even today, and as a result, published examples of Klimt's most erotic drawings are not always easy to locate.

This drawing, which dates from the later part of Klimt's career, is a typical example of his erotic oeuvre. The sketch of a woman reclining and touching her genitals simply gives the barest essentials of the contours of the figure, with even less detail as to the surfaces and spaces surrounding her. We are not even sure if much of her torso is covered in a bedsheet or a piece of clothing, or even what the surface is underneath her. The most detailed portion of the drawing, perhaps appropriately, is the region containing her hand and pubic hair. This, in combination with the looseness of the rest of the drawing - which, as a result, leaves much for the viewer's imagination to fill in - helps to heighten its overall eroticism. Yet another layer of salaciousness from the imagination is arguably added by the anonymity to us of many of Klimt's models.

As famous as Klimt's eroticism may be, his forays into this area are hardly unique. Klimt himself, as art historian Kirk Varnedoe has noted, likely saw on several occasions Rodin's similar loose renderings of female nudes, often in quite explicit poses, dating from the late 1890s and onwards. Klimt's own artistic expression may pale in comparison to that of his student Egon Schiele, whom Klimt introduced to various models while the former was under his tutelage. In part this is because Klimt - especially after the University paintings controversy - took pains to be publicly discreet about his sketches and other studio activities. By contrast, Schiele, was known during his short career for his repeated run-ins with authorities for the nude models - including some children - that he employed, many of whom Schiele depicted in similarly explicit poses.

Blue pencil on paper - Collection of the Vienna Historical Museum

Biography of Gustav Klimt

Childhood

Born to Ernst Klimt, a gold engraver who was originally from Bohemia, and Anna Finster, an aspiring but unsuccessful musical performer, Gustav Klimt was the second of seven children raised in the small suburb of Baumgarten, southwest of Vienna. The Klimt family was poor, as work was scarce in the early years of the Habsburg Empire, especially for minority ethnic groups, due in large part to the 1873 stock market crash.

Between 1862 and 1884, the Klimts moved frequently, living at no fewer than five different addresses, always seeking cheaper housing. In addition to financial hardships, the family experienced much tragedy at home. In 1874 Klimt's younger sister, Anna, died at the age of five following a long illness. Not long after, his sister Klara suffered a mental breakdown after succumbing to religious fervor.

At an early age, Klimt and his two brothers Ernst and Georg displayed obvious artistic gifts. Gustav, however, was singled out by his instructors as an exceptional draftsman while attending secondary school. In October 1876, when he was fourteen, a relative encouraged him to take the entrance examination for the Kunstgewerbeschule, the Viennese School of Arts and Crafts, and he passed with distinction. He later said that he had intended to become a drawing master and take a teaching position at a Burgerschule, the 19th-century Viennese equivalent of a basic public secondary school, which he had attended.

Klimt began his formal training in Vienna while the city was undergoing significant change. In 1858, Emperor Franz Joseph I ordered the destruction of the remnants of the old medieval defensive walls that encircled the central part of the city, leaving a large circular space that was redeveloped as a series of broad boulevards known as the Ringstrasse ("ring street"). Over the next thirty years, the Ringstrasse became lined with trees and large bourgeois apartment houses, as well as many new buildings to house various civic and imperial government institutions, including theaters, art museums, the University of Vienna, and the Austrian Parliament building. Along with the newly constructed municipal railway, the arrival of electric street lamps, and city engineers rerouting the Danube River in order to avoid flooding, Vienna was entering a Golden Age of industry, research, and science, driven by modern advancements in these fields. One thing Vienna did not yet have, however, was a revolutionary spirit towards the arts.

Training and Early Success

The Kunstgewerbeschule's curriculum and teaching methods were fairly traditional for their time, something Klimt never questioned or challenged. Through an intensive training in drawing, he was charged with faithfully copying decorations, designs, and plaster casts of classic sculptures. Once he proved himself in this regard, only then was he permitted to draw figures from life. Klimt impressed his instructors from the very beginning, soon joining a special class with a focus on painting, where he showed considerable talent for painting live figures and working with a variety of tools. The young artist's training also included close studies of the works of Titian and Peter Paul Rubens. Klimt also had access to the Vienna Museum of Fine Arts' wealth of paintings by Spanish master Diego Velázquez, for whose work he developed such a fondness that later in life, Klimt remarked, "There are only two painters: Velázquez and I."

Klimt also became a huge admirer of Hans Makart (the most famous Viennese historical painter of the era), and particularly his technique, which employed dramatic effects of light and an evident love for theatricality and pageantry. At one point, while still a student, Klimt reportedly bribed one of Makart's servants to let him into the painter's studio so that Klimt might study the latest works in progress.

Shortly before leaving the Kunstgewerbeschule, Klimt's painting class was joined by his younger brother Ernst and a young painter named Franz Matsch, another gifted Viennese artist who specialized in large-scale decorative works. Klimt and Matsch both ended their studies in 1883, and together the two rented a large studio in Vienna. Despite this move and his early success, Klimt maintained residence with his parents and surviving sisters. Klimt and Matsch soon became artists in high demand among the city's cultural elite, including prominent architects, society figures, and public officials. As early as 1880, Klimt and Matsch were recommended by their painting professor, Ferdinand Laufberger, to undertake a four-painting commission on behalf of a Viennese architectural firm specializing in theater design.

Despite the demand, payment for Klimt and Matsch's services was not lucrative. When Klimt, his brother Ernst, and Matsch were handed the job to decorate the grand stairway of the new Burgtheater, the trio found that their commission would not cover the costs of hiring models, so they enlisted friends and family. Today one can see Klimt's sisters Hermine and Johanna (along with all three artists) among the spectators in Shakespeare's theatre, while their brother Georg plays the dying Romeo. Incidentally, this is the only surviving self-portrait of Klimt.

Mature Period

By the end of 1892, both the senior Ernst Klimt - Gustav's father - and his younger brother Ernst had died, the latter quite suddenly from a bout of pericarditis. These deaths profoundly affected Gustav, who was now left financially responsible for his mother, sisters, brother's widow, and their infant daughter. His brother Ernst's widow, Helene Flöge - to whom he had been married for a mere fifteen months - and her middle-class family had homes in both the city and country, where Klimt became a frequent guest. Klimt soon began an intimate friendship with Helene's sister, Emilie Flöge, which would last for the remainder of his life and provide the basis for one of his most famous portraits.

Klimt's pace of work slowed following the deaths of his brother and father. The artist also began questioning the conventions of academic painting, which resulted in a rift between Klimt and his long-time partner Matsch. In 1893, the Artistic Advisory Committee of the Ministry of Education approached Matsch for a commission to decorate the ceiling of the newly built Great Hall of the University of Vienna. Klimt did eventually join the project (whether at the request of Matsch or the Ministry), but this collaboration would be the last between the two men.

Klimt was asked to produce three large ceiling paintings for the university's Great Hall, including Philosophy (1897-98), Medicine (1900-01), and Jurisprudence (1899-1907). To his commissioners' surprise, for these paintings Klimt chose to employ a highly decorative symbolism that is difficult to read, thus marking a significant turn in his attitude toward painting and art in general. Significant controversy arose over Klimt's University paintings, especially due to the nudity of some of the figures in Medicine, and in part to accusations that the subject matter was vague. The University paintings were never installed, and in the aftermath of the controversy, Klimt resolved never to accept again a public commission.

Founding the Vienna Secession

Klimt's work on the University of Vienna paintings coincided with a broader schism within the Vienna art community. In 1897 he, along with several other modern artists and designers, renounced his membership in the Kunstlerhaus, Vienna's leading association of artists, of which Klimt had been a member since 1891. The Kunstlerhaus controlled the main venue for exhibiting contemporary art in the city, and Klimt and his fellow modernists complained that they were being denied the same privileges of exhibiting work there because the Kunstlerhaus, which took a commission on works displayed there, favored the better-selling conservative works.

The modernist cohort immediately regrouped to found the Vienna Secession (also known as The Union of Austrian Artists) in 1897. Along with Klimt, the group included Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, and Joseph Maria Olbrich. Klimt was made the Secession's founding president. Its founding principles were as follows: to provide young and unconventional artists with an outlet to show their work; to expose Vienna to the great works of foreign artists (namely the French Impressionists, which the Kunstlerhaus had failed to do); and to publish a periodical, eventually titled Ver Sacrum ("Sacred Spring"), which took its name from the Roman tradition of cities sending younger generations of its citizens out on their own to found a new settlement.

The Secession quickly established its presence within the city's artistic scene through a series of exhibitions, which Klimt played a large role in organizing. Many of them featured work by foreign contemporary artists who were made corresponding members of the group. The exhibitions received wide acclaim from the public and elicited surprisingly little controversy, given that the Viennese had little to no exposure to modern art. In 1902, the Secessionists held their 14th exhibition, a celebration of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven, for which Klimt painted his famous Beethoven Frieze, a massive and complex work that, paradoxically, made no explicit reference to any of Beethoven's compositions. Instead, it was seen as a complex, lyrical, and highly ornate allegory of the artist as God.

Though the Secession was dedicated to the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or the completely and harmoniously designed environment, it attempted to keep art above the realm of commercial concerns, which proved problematic for its members, most notably decorative artists, whose work in designing useful objects demanded a commercial outlet to be successful. In 1903, two of its prominent members, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, formed a new organization, the Wiener Werkstätte, dedicated to the promotion and design of decorative arts and architecture for such purposes. Klimt, who was close to both Hoffmann and Moser, would thereafter collaborate on several of the Werkstatte's projects, most notably the giant multi-panel tree-of-life painted frieze for the Palais Stoclet in Brussels, the greatest Gesamtkuntswerk produced by the Werkstatte, between 1905-10.

In 1905, Klimt and a number of his associates resigned from the Vienna Secession due to a disagreement over the group's association with local galleries, which were not especially strong in Vienna, to market their art. Despite having their own exhibition space, the Secessionists were still dogged by a lack of a systematic location to complete the sale of their work. The Klimtgruppe (as Klimt and his supporters, including Moser and Josef Maria Auchentaller were known) proposed that the Secession purchase the Gallery Miethke, but were rejected by one vote when the suggestion was put before the membership, as the opposition wished to keep the Secession fully separate from commercial interests. The Klimtgruppe's resignation gutted the Secession of its most internationally prominent members; nonetheless, in the years since it has reinvented itself many times - often coinciding with changes in leadership - and today it remains the only Austrian artist-run society dedicated to the promotion of contemporary art.

Late Period and Death

In the decade between 1898 and 1908, while working as a member of the Secession and on the commissions for the University, Klimt's personal style, which richly combined elements of both the pre-modern and modern eras, reached its full maturation. He produced several of his most famous works during these years that together now comprise his "Golden Phase," so-called largely due to Klimt's extensive use of gold leaf. These paintings include Field of Poppies (1907), The Kiss (1907-08) along with the portraits Pallas Athene (1898), Judith I (1901), and Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1903-07). Despite the respect accorded them today, the reception at the time was not always as kind: one critic quipped upon seeing Bloch-Bauer I for the first time that it was "more blech than Bloch" ("blech" actually being the German word for tin). If Klimt disliked the response to his paintings, he was probably glad that critics never got to see his sketchbooks, as Klimt was in some ways the early-20th-century male equivalent of the stereotypical crazy cat lady. He claimed that cat urine was the best fixative, and so his sketchbooks are often covered in it.

In the last decade or so of his life, Klimt divided much of his time between his studio and garden in Heitzing, in Vienna, and the country home of the Flöge family, where he and Emilie spent much time together. Although there was unquestionably a romantic bond between them, it is widely believed the two never gave in to physical desire. Their closeness, however, did not soften Klimt's dislike for using written language: in one letter to Emilie, he got so frustrated that he simply wrote, "To hell with words!" Klimt was equally terse and uncomplimentary when discussing places he had visited; on one visit to Italy, he could only report back to Emilie that "there is much that is pathetic in Ravenna - the mosaics are tremendously splendid."

During these summers Klimt produced many of his stunning (yet frequently underappreciated) en plein air landscape paintings, such as The Park (1909-10), often from the vantage point of a rowboat or an open field. Klimt had two loves: painting and women, and his appetite for both was seemingly insatiable. Klimt's personal life, about which he took pains to be discreet, has as a result become quite famously the subject of considerable speculation amongst critics and historians, especially given Klimt's numerous portraits of women. In many cases, no consensus has been reached on Klimt's involvement with certain individual women; while many reports swear by Klimt's intimate liaisons, others - in part due to the lack of hard evidence - doubt that there was any romantic involvement between Klimt and those same sitters.

While Klimt did not alter his subject matter during his final years, his painterly style did undergo significant changes. Largely doing away with the use of gold and silver leaf, and ornamentation in general, the artist began using subtle mixtures of color, such as lilac, coral, salmon and yellow. Klimt also produced a staggering number of drawings and studies during this time, the majority of which were of female nudes, some so erotic that to this day they are seldom exhibited. At the same time, many of Klimt's later portraits have been praised for the artist's greater attention to character and a supposed new concern for likeness. These features are evident in Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912) and Mada Primavesi (1913), as well as the strangely erotic The Friends (c. 1916-17), which portrays what appears to be a lesbian couple - one naked and the other clothed - against a stylized backdrop of birds and flowers.

On January 11, 1918, Klimt suffered a stroke, which left him paralyzed on his right side. Bedridden and no longer able to paint or even sketch, Klimt sank into despair and contracted influenza. On February 6th he died, one of the more famous victims of that year's flu pandemic. He was just one of four great Vienna artists to die that year: Otto Wagner, Koloman Moser, and Egon Schiele all succumbed, the latter also an influenza victim. By the time of his death, various strands of modern art, including Cubism, Futurism, Dada and Constructivism, had all captured the attention of creative Europeans. Klimt's body of work was by then considered part of a bygone era in painting, which still focused on human and natural forms rather than a deconstruction, or outright renunciation, of those very things.

The Legacy of Gustav Klimt

Klimt never married; never painted a single self-portrait intended as such; and never claimed to be revolutionizing art in any way. Klimt did not travel extensively, but he did leave Austria on a number of visits to other locations in Europe (although on the one occasion he visited Paris, he left thoroughly unimpressed). With the groundbreaking Secession, Klimt's primary aim was to call attention to contemporary Viennese artists and in turn to call their attention to the much broader world of modern art beyond Austria's borders. In this sense Klimt is responsible for helping to transform Vienna into a leading center for culture and the arts at the turn of the century.

Klimt's direct influence on other artists and subsequent movements was quite limited. Much in the way Klimt revered Hans Makart but eventually deviated from his mentor's style, younger Viennese artists like Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka revered Klimt early on, only to mature into more quasi-abstract and expressionistic forms of painting. At the age of 17, Schiele sought Klimt out, and developed a friendship with the master that reveals itself today in several comparisons between their works; Schiele's Cardinal and Nun (Caress) of 1912, for example, is undoubtedly based on Klimt's The Kiss (Lovers) of 1907-08. Klimt introduced Schiele to numerous gallery owners, artists, and models, including Valerie (Wally) Neuzil, with whom Schiele began a relationship in 1911 around the time the two moved together to Krumau, in Bohemia (now Cesky Krumlov, in the Czech Republic) - though in 1916 Neuzil returned to Vienna to model again for Klimt. Both Schiele and Klimt produced portraits of the wealthy avant-garde patron Friederika Maria Beer-Monti, in 1914 and 1916, respectively; in fact, initially Klimt declined the commission for the later portrait of Beer-Monti because Schiele had already completed his.

While some critics and historians contend that Klimt's work should not be included in the canon of modern art, his oeuvre - particularly his paintings postdating 1900 - remains striking for its visual combinations of the old and the modern, the real and the abstract. Klimt produced his greatest work during a time of economic expansion, social change, and the introduction of radical ideas, and these traits are clearly evident in his paintings. Klimt created a highly personal style, and the meaning of many of his works cannot be deciphered completely without knowledge of his own personal relationships with those depicted and, due to Klimt's careful discretion in his private life, will probably never be fully comprehended. Other works are virtually inscrutable due to the baffling arrangements of their content. This situation nonetheless arguably contributes to Klimt's stature, as his paintings will continually be shrouded in some sort of mystery and invite myriad interpretations and intense critical rumination.

Klimt has achieved a kind of immortality from the controversy that he generated from the content of his works at the turn of the century and the mystery surrounding his relationships with his sitters, but he may have even surpassed this long after his death with the fates of some of his most famous works. Several of Klimt's paintings entered the collections of Jewish connoisseurs in the 1930s, and this fact, probably combined with Klimt's status as a prominent modern artist, contributed to their confiscation by the Nazis after 1938 and their postwar placement, if not destroyed, in state museums. Meanwhile, the original owners and their heirs - most notably the Altmann family, who held claims to Klimt's Adele Bloch-Bauer I - have since filed lawsuits to recover the paintings for private ownership, some of which have been successful. Such events have raised considerably Klimt's profile as an artist, with the sale of some of these recovered works bringing record prices.

Influences and Connections

-

![Hans Makart]() Hans Makart

Hans Makart ![Margaret MacDonald]() Margaret MacDonald

Margaret MacDonald![Max Klinger]() Max Klinger

Max Klinger

![Adolf Loos]() Adolf Loos

Adolf Loos![Franz Matsch]() Franz Matsch

Franz Matsch![Emilie Floge]() Emilie Floge

Emilie Floge![Josef Hoffmann]() Josef Hoffmann

Josef Hoffmann

![Josef Hoffmann]() Josef Hoffmann

Josef Hoffmann![Joseph Maria Olbrich]() Joseph Maria Olbrich

Joseph Maria Olbrich![Koloman Moser]() Koloman Moser

Koloman Moser![Otto Wagner]() Otto Wagner

Otto Wagner

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI