Summary of Ibram Lassaw

Ibram Lassaw, one of America's first abstract sculptors, was best known for his open-space welded sculptures of bronze, silver, copper and steel. Drawing from Surrealism, Constructivism, and Cubism, Lassaw pioneered an innovative welding technique that allowed him to create dynamic, intricate, and expressive works in three dimensions. As a result, he was a key force in shaping New York School sculpture.

Accomplishments

- Rather than communicating a specific idea or representation, Lassaw sought to present a structure that was meaningful purely in itself and did not intend for his works' titles to shape audience interpretation of his sculptures.

- Drawing on an interest in the internal structures found in nature, cosmology, astronomy, and technological construction, Lassaw aimed to entice viewers to lose themselves within his sculptures' complex interiors. This creation and enclosure of internal space later became prevalent in Minimalist sculpture.

- Through his commitment to an intuitive construction of space and unconsciously driven application of melted metals, Lassaw developed an aesthetic similar to the instinctual painting compositions of his Abstract Expressionist peers, such as Jackson Pollock, who relied on a kind of trance-like automatism to structure their compositions.

Important Art by Ibram Lassaw

Sculpture in Steel

After experimenting with plaster, rubber and wire, Lassaw began working with steel, which became a frequent medium for the artist, along with other metals. Sculpture in Steel, composed of biomorphic forms, reflects the important influence Surrealists such as Alberto Giacometti and Joan Miró had on Lassaw. This sculpture, Lassaw's first crafted from welded sheet metal, also reveals the distinct influence of Alexander Calder's mobiles. Around this time, Lassaw was also creating shadowbox sculptures and other works shaped around similar rectangular frames, beginning to develop pieces that depended on and created empty space as a structural element.

Steel - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Milky Way

Milky Way is notable for signaling a new direction in Lassaw's mature open space style. He considered it his breakthrough sculpture. Here Lassaw was able to work without the rigid framework he had used to support more delicate organic forms. Previous efforts to work in this style has failed due to the use of structurally poor materials such as plaster and metalized compounds. The work is made from a plastic-metal paste which could be applied and shaped by a palette knife over sturdy wire before it hardened. Although this was not the most perfect material for sculpture, Milky Way still stands strong sixty-six years after it was created. Lassaw had a life long interest in all sciences and astronomy, and he used titles with cosmological references because he wanted viewers to experience the work directly without the conceptual baggage a recognizable name would have.

Plastic-metal compound - Denise Lassaw Collection

Kwannon

In 1951, after making his first sale, Lassaw was at last able to buy oxyacetylene welding equipment to create sculptures in metal. This work, which followed the morphology of his first 18 welded sculptures was created by first bending and shaping galvanized wire and then fusing molten bronze in layers to build up thickness and strength. The title, Kwannon is the Japanese name for the Buddhist Goddess of mercy and compassion.

Welded bronze and nickel-silver - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Counterpoint Castle

Lassaw continued to expand his explorations and variety of space textures using copper tube shapes which he made and covered with bronze, with the thin wire shapes. Lassaw used various metals for their colors but in Counterpoint Castle he added the use of acids to turn some areas of the sculpture blue.

Bronze and copper - Denise Lassaw Collection

Banquet

Banquet exemplifies Lassaw's use of a technique he developed in which molten metal is built up by fusing globs of metal together, similar to the accretion of stalagmites. The work grows spontaneously, as Lassaw has written, "The work is a 'happening' somewhat independent of my conscious will. The work uses the artist to get itself born." Some people think sculptures like Banquet look like coral, however that was not Lassaw's intention. The morphology of Banquet and the morphology of coral, like other crystalline structures found in nature may appear similar.

Bronze, bronze alloys, and steel - National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian, Washington DC

Vortex F

In addition to the sculptural works for which he is primarily known, Lassaw also produced many drawings, lithographs and works on canvas and paper, much of which demonstrated a spatial interest similar to that of his three-dimensional works. The forms created by empty space in Vortex F are as important, if not more important, than the lines themselves. Here, as in many of his works, Lassaw combined geometric and biomorphic shapes, drawing the viewer's eye into the maze-like composition.

Acrylic on paper - The Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, NY

Biography of Ibram Lassaw

Childhood

Ibram Lassaw was born in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1913 to Russian-Jewish parents. After briefly living in Marseille, Naples, Tunis, Malta, and Constantinople, his family settled in Brooklyn, New York, in 1921. Lassaw was very interested in art from a young age and worked in clay from the age of four. He also created animals and figures using pieces of tar from the street. The history of art fascinated him, and at age 12, he started amassing an extensive collection of clippings and art reproductions, eventually filling 33 scrapbooks.

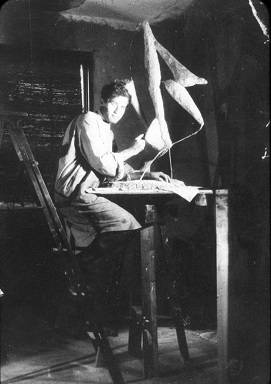

Early Training

Lassaw had his first formal training in 1927 with classes at the Brooklyn Children's Museum, which later became the Clay Club (now the Sculpture Center) taught by Dorothy Denslow. At the Clay Club until 1932, Lassaw learned modeling and casting, skills that he refined during his year at the Beaux Arts Institute of Design (1930-31).

In 1931, he also spent a year studying at City College of New York. Continuing to expand his interest in all forms of art, he pored over many issues of the influential Cahiers d'Art, through which he learned about the art of the Cubists, Futurists, Constructivists, Dadaists, and Surrealists. He became particularly interested in the use of new and unconventional materials to create artwork, as well as in the concept of sculptures that either contained or were structured by open spaces.

Mature Period

Lassaw had started to experiment with abstracted forms in the previous years, but 1933 marked a definitive shift toward open-space based abstracted sculpture. The first of these open-space sculptures were created between 1933 and 1934, made from plaster on wire armatures. Beginning in 1933, Lassaw also became involved with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) of the Federal Arts Project and similar organizations. He co-founded American Abstract Artists in 1936 and later served as the organization's president from 1946 through 1949. During this time, Lassaw was working with a broad range of materials, maintaining his interest in untraditional media, particularly those that referenced technology, such as steel and iron. His sculptures from this period ranged from ornate and baroque to rectilinear and precise. Three of his open-space works, Sculpture (aka Pot Jumping Through Hoop) (1935), Sculpture (1936), and Sing Baby Sing (1937), all made using plaster and wire, were exhibited at the first group show of the American Abstract Artists, at the Squibb Gallery, in 1937. None of these works survive.

By the late 1930s, Lassaw moved from plaster or wood on wire to sheet metal and hammered forged steel. He also created shadowbox pieces that integrated illumination. In the 1940s, he began concentrating on rectilinear shapes, but his artistic focus was interrupted by army service; from 1942 to 1944, he served in the U.S. Army in Virginia, where he learned to weld while fixing army vehicles.

Beginning in 1946, following Lassaw's discharge from the army, the artist created a series of hand-painted "projection paintings." These miniature Abstract Expressionist paintings were applied to 2x2-inch glass slides that, when viewed through a projector, cast an array of colored-light images. Unlike abstract paintings, which could be rotated on the wall and viewed from four different perspectives, Lassaw's "projections" could be rotated and turned around, offering the viewers eight different possible vantage points. By 1949, Lassaw stopped producing these paintings and devoted himself almost entirely to sculpture, but he would revisit the medium later in life.

Lassaw's return to sculpture also marked his moving away from purely geometric shapes towards biomorphic forms. He began integrating additional media, such as plastic and Plexiglas, also adding dye to the sculptures to integrate color. In 1949, Lassaw became one of the founders of The Club, the informal, but influential, discussion forum of New York School artists that included Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. By the early 1950s, he had purchased oxyacetylene welding equipment and identified the ideal medium for his mature style: using molten metal, he created sculptures "drop by drop," a method in which the red-hot metal, brought to varying degrees of temperature and consistency, was carefully directed through a funnel-like device. The resulting product was a type of spontaneous and instinctive sculpture similar to the Action Painting of his New York School peers. Lassaw had his first solo exhibition in 1951 at the Kootz Gallery. That same year, he sold his first major sculpture to Nelson Rockefeller, who eventually purchased ten more Lassaw works, all of them pendants. Lassaw continued expanding his welding work, adding color by treating the metal with additives, and integrating minerals and semiprecious stones. With the help of gallery owner Samuel Kootz, who facilitated most of Lassaw's commissions, the artist regularly showed works in group shows and enjoyed almost annual solo exhibitions at the Kootz Gallery right up until the gallery's closing in 1966.

Late Period

Lassaw created his first public commission in 1953, Pillar of Fire for Congregation Beth-El in Springfield, Massachusetts, and completed others including a wall sculpture, Clouds of Magellan, for Philip Johnson's Glass House (1953), Pillar of Cloud for Temple Beth-El in Providence, Rhode Island (1954), a monumental sculpture for the entrance of the New Arts Building at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri (1959), and Elysian Fields for the New York Hilton Hotel (1963). Having purchased land in The Springs, East Hampton, in 1954, Lassaw moved there full-time with his wife in 1962. Other New York School artists frequented the area such as de Kooning and Pollock.

Lassaw taught at Duke University, University of California, Berkeley, Southampton College, and Mount Holyoke College during the 1960s and 1970s. While sculpture was his primary art form, Lassaw also continued to produce lithographs, drawings on paper, photographs, "projection paintings," and jewelry. By the mid-1990s Lassaw's eyesight had deteriorated to the point where he could no longer weld metals, but this did not stop him from working in other media. Lassaw remained in The Springs on Long Island and continued to work, even producing paper drawings right up to the late morning of December 29, 2003, less than 24 hours before his death.

The Legacy of Ibram Lassaw

Lassaw's innovative welding techniques, manipulation of diverse materials and fascination with creating space through sculptural forms distinguished his work from that of his contemporaries and predecessors, while at the same time connected him to the aims and concepts of Abstract Expressionism. He was a crucial part of the New York School, both artistically and socially, and instrumental in garnering attention for sculptural Abstract Expressionist work.

Influences and Connections

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI