Summary of Wyndham Lewis

Wyndham Lewis was an English artist and writer best known as the founder of the Vorticist movement. Having travelled to Paris to study painting in the early years of the twentieth century, he returned to London in 1908 where he was amongst the first British artists to champion the virtues of Expressionism and Cubism. Soon, he would be creating paintings that borrowed the geometric forms of Cubism which he applied to images of machines and architecture. The name Vorticism, meanwhile, was derived from the idea that the tumultuous modern world should be viewed through the prism of a spiralling vortex. Lewis published two editions of Blast, a Vorticist journal that attacked the values of Victorian England and featured Imagist (anti-romantic) poetry and radical graphic design. He then served in the First World War as an artillery officer before being commissioned as a war artist (though his finished paintings were not to everyone's tastes). Lewis continued to paint after the war, moving into portraiture. He also devoted more time to writing and published a collection of books, short stories and essays. Lewis was a socialite and one of the true personalities of early-to-mid twentieth century British art. But his cavalier attitude towards modern life and human relationships, not to mention his early support for the Nazi party, mean that it has often proved difficult for critics to separate Lewis "the personality" from his art.

Accomplishments

- Though sometimes labelled a Futurist (probably because of his close friendship with Filippo Tommaso Marinetti), Lewis was scathing of Futurism and its naïve glorification of modernity. His ink drawings and paintings were, like the Futurists, full of dynamic, angular, movements but Lewis's work revealed a much more balanced and circumspect view of the machine age.

- Lewis was a radical and wanted to challenge compositional harmony in painting. His Vortist cityscapes, represented as bold geometric lines that criss-crossed his canvases at sharp angles, were perfectly matched to the noisy, chaotic and claustrophobic London in which he was living. Indeed, Lewis can take credit for representing a picture of modern living that was unlike anything British painting had ever seen before (or since).

- Neither decorous nor commemorative, Lewis applied his inimitable Vortist style to war painting, producing what would be some of the most controversial art to come out of the war (certainly in Britain). Using a non-naturalistic palette to heighten contrasts, his jagged and jarring Vortist style was suited perfectly to representing the killing machines or war and the unforgiving landscape on which he himself had fought.

- A committed socialite, Lewis was commissioned to produce portraits by several of his eminent friends (including T. S. Elliot, Ezra Pound and Edith Sitwell). Of all his works, his portraits owed most to the great artists in whose footsteps he was following. There are obvious nods to Cubism in his faceted geometric lines, for instance, yet his portraits brought something unique to the genre in the way that he imbued his sitters with an almost robotic machine-like quality.

The Life of Wyndham Lewis

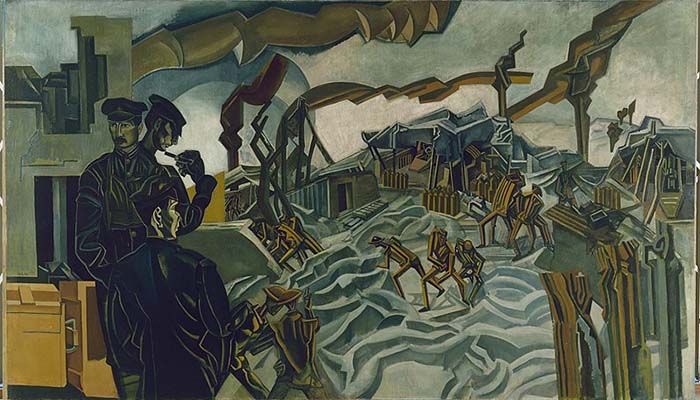

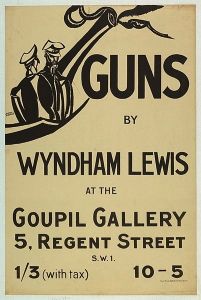

Lewis powerfully utilized the ideas of Cubism and Futurism to create truly original art - such as this scene A Battery Shelled (1919) which depicts the difficulties of the battle front.

Important Art by Wyndham Lewis

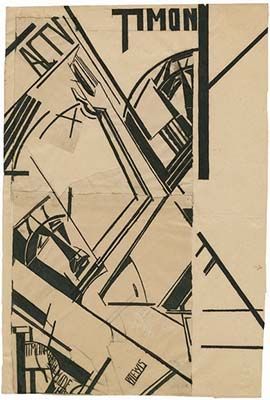

Plate from set of illustrations to Shakespeare's Timon of Athens

In the late summer of 1912, Lewis spent time in Dunkerque, working on a series of drawings to accompany a folio edition of Shakespeare's Timon of Athens. When he presented it to the publisher Evelyn Benmar, as biographer Paul O'Keeffe observed, Benmar was appalled, stating: "'that's mania, not art!' But on closer inspection Mr Benmar [soon] recognized the artist's 'genius'".

The pen-and-ink drawing is clearly Cubist-inspired in its bold lines, fragments, and geometric shapes. At the top the text clearly states "Timon" and to the left we see "Act V". Timon himself is depicted with his arms raised in prayer, creating an "X" shape with reflecting lines, prefiguring Lewis's veneration for the form with his "Group X". (This Modernist cruciform is repeated in a smaller size across the print.) Just as Lewis was not the best known of the Modernists, Timon of Athens is not the best known of Shakespeare's plays. The title character has a lot in common with Lewis - namely his misanthropy - but Lewis described Timon as "noble and immaculate".

Lewis Biographer Paul Edwards wrote: "Our perception of fragments of figures and lettering out of these blocks, arcs and lines tends to be provisional, as the design takes on different readings with shifts in the viewer's attention [...] Typically, Lewis does not enclose the forms of his solids, and they become momentary configurations of the elements that compose them, inseparable from those elements and the transient acts of perception through which they are constructed". The work can be read in terms of Lewis's critique of Futurism, Edwards writes. Although Lewis moved in the same circles as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti - the father of Futurism - and much of the two artists' work share the same tenets, Lewis spoke derogatorily of the Italian. Marinetti demanded that Lewis was a Futurist, while Lewis vehemently denied it, even disrupting one of the Italian's lectures in London. Lewis loved the movement's dynamic qualities but dismissed what he saw as its uncritical enthusiasm for modernity. Edwards concluded: "He saw in the savage invective and brutal imagery of Timon of Athens a vehicle for his own critical attitude to Modernist fantasies of the total transformation of life".

Pen and ink drawing - Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC, USA

Workshop

Workshop was an early Vorticist work representing the crowding towers and architecture of a city on the cusp of war. Bold geometric lines extend diagonally across the canvas, abstracting the blocks and walls of a growing London. Ladder-like planes and patterns of squares lead the eyes around the work, bringing them up towards the distant window of blue sky in the centre top, while a rectangular overhang sends them back down, lending a note of claustrophobia to the piece. There is a sharp contrast between the blue, representing a tiny patch of nature, and the many browns, ochres and pinks of the man-made. Shapes and colors jar as the artist strived to produce an art that matched the energy of the modern world. For Lewis, art was always superior to life, and with this work he wanted to present an "attack on traditional harmony".

As art historian Michael Prodger said, "Vorticism sought to reflect the dynamism of the modern world through angular, fractured, urban and machine-based imagery". Here Lewis wanted to represent the noise and dynamism of London - but this work goes further in reflecting how the urban landscape changed the very way the artist saw. Lewis himself wrote: "A man who passes his days amid the rigid lines of houses, a plague of cheap ornamentation, noisy street locomotion, the Bedlam of the Press, will evidently possess a different habit of vision to a man living amongst the lines of a landscape."

Despite Lewis's wish to distance Vorticism from Futurism and Cubism, their influence here is in abundance through the use of bold line and fractured shape and in the celebration of the man-made. In Blast, Vorticism's manifesto, Lewis "blasted" "bourgeois Victorian vistas" and "blessed" "the steep walls of factories" and England as an "industrial island machine". The painting acted as a vacuum, said art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon: "To look at Workshop is to see so much that had been omitted from art in Britain since the middle of the nineteenth century - bright colour, the shapes of modern engineering and architecture, a sense of visual excitement and exhilaration in the face of change - suddenly rushing into English painting".

The work shocked the British public at the time. At the only Vorticist group exhibition in Britain, in June 1915, the Daily Mirror's art critic wrote that many of the painters had enlisted in the Army, adding: "It is evident that in combat somebody has been badly knocked about".

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

The Crowd

The themes of Workshop are further explored in The Crowd, the only one of Lewis's Vorticist paintings to survive to this day. Art Critic Mark Hudson described it as "a quintessential Modernist city-scape, at once euphoric and slightly nightmarish, with asymmetric grid-forms offset by busier cell-like structures, all in rich oranges and yellows".

As in Workshop we see the urban setting, the grids and ladders, the earthy tones and geometric forms. But in this work humans have been introduced, albeit in robotic form. Brown and red tower blocks tussle for space in the unsettling scene. There is a heavy absence of blue sky or nature, as collections of apparent humanoids bustle up and down the work, often indivisible from the crowd in which they find themselves. People, dwarfed by the buildings surrounding them are rendered stick-like and frantic. The work was designed to examine the instinctive behavior of people in crowds and Lewis presented them climbing, scuffling and scurrying like ants in a farm. The eye is drawn to the very centre of the work where someone waves a red flag. On the bottom left however, another figure waves a tricolor - indicating opposition or protest. Indeed, the work's working title was Revolution.

Art historian Michael Prodger described the work as the purest example of Lewis's Vorticism. He said the work represented "a schematic metropolis - part Fritz Lang and part Mondrian gone wrong - crawled over by tiny, rudimentary figures. A flag and men with banners suggest this might show an insurrection but it is nevertheless redolent of Lewis's belief that modern man was at heart a dehumanised automaton driven by base passions." Indeed, the work prefigured the most disastrous century of conflict, resolution and alienation in human history.

Oil on canvas - Manchester Art Gallery, UK

A Canadian Gun Pit

Lewis described the First World War as "a black solid mass, cutting off all that went before it" and as a "stupid nightmare". This piece depicts the boredom and physical labor involved in what could also be incredibly dangerous work. Lewis drew on his own experiences in the artillery for the work, which shows ten soldiers in the foreground of the gun pit, preparing the shells to be shot from the enormous gun to the left. Lewis creates tension with the bright orange and purple palette and the sharp diagonals of the gun, the clouds and the canvas which jars with the boredom on the men's faces and the uniformity of the mortars, lined up ready to cause death and disruption. To the top left, trees have been blasted, leaving denuded trunks reaching into nowhere. A note of menace is added in the bent-over soldier's face which Paul Edwards pointed out "is suggestive of a skull with metallic sinews".

In the background meanwhile, the recurring motif of the dehumanization of man can be seen in the working figures, reminiscent of those from The Crowd, as the human figures submit to the larger architectural machine in which they find themselves trapped. Modernist scholar Dr Alan Munton wrote: "These men are all subject to the dangerous machine that they operate, and to its brutal requirements. This work shows the gunpit before firing begins: the gun is being 'laid', or aimed. We can see in the distance the destruction that has already occurred, and there will be more very soon. For the viewer this is not a moment of trauma, but rather of contemplation".

Art Critic Laura Freeman observed: "[Lewis] did not paint the war like Goya, but in the fidgety, jagged style of Vorticism. It was right for the pitted, splintered, broken landscape of France, and the shell-shocked, sleepless men who fought there". The work earned Lewis £300 from the Canadian War Memorials Committee, but a more challenging war image was yet to come.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery of Canada, Ottowa, Canada

A Battery Shelled

A Battery Shelled would not have been accepted by the Canadian War Memorials Committee, as Cubist work was deemed inadmissible. This work, however, arguably Lewis's most famous, was commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee who allowed the artist greater artistic freedoms. The heavily stylized composition shows the scene from the First World War in which enemy barrages were being suppressed by counter-battery work. The three soldiers in the foreground, rendered in dark greens, blue and black, look in different directions, standing calmly before the devastation in the background. Officers beyond are reduced into robotic or marionette-like forms, working or hurrying for cover amid smoke and destruction. They are rendered insect-like and faceless, and are further dehumanized by their colors and contours, similar to the waiting crowds of mortars. The cold expressions of the three soldiers match the palette and the cold, emotionless detachment with which Lewis presents the scene.

Art critic Jonathan Jones drew attention to the differentiation between three soldiers at the front and those running in terror beyond: "A group in the foreground are more characterful. They stand pensively, reflecting on the shattered Vorticist battlefield. Why are some human and others not? This painting lets us into the psychology of war. Enemy soldiers and even comrades can seem distant, remote, unreal. In war, you save yourself by effacing fellowship with others".

The work was inspired by Lewis's own experience on the battlefield - he'd served in the Royal Artillery at Passchendaele. In both style and content the work was one of the most controversial to come out of the First World War. As art historian Michael Prodger explained: "When it was exhibited at the Royal Academy neither its enigmatic nature nor its avant-gardism appealed to audiences that wanted something more seemly and obviously commemorative, and the painting was embarrassedly offloaded by the war art committee to the Imperial War Museum".

Oil on canvas - Imperial War Museum, London

Edith Sitwell

In his later years, Lewis found portraiture provided a useful source of income, and produced a number of images depicting his famous friends, including TS Eliot, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, and, in this image, the cultural luminary Edith Sitwell. The work took twelve years to complete, and it was an arduous process for the model, requiring months spent in Lewis's rat-infested room. (Although she never saw a rat, she complained of rustling in the rubbish that covered the filthy floor.) Sitwell later wrote: "The studio [...] was very large, and the floor was crowded with old newspapers, books, drawings, housemaids' worries, pots, pans, kettles, a tea pot, tins of milk and Mr Lewis's discarded undergarments".

The domestic reality of the situation is not reflected in Sitwell's serene pose, however. The calming blues and greens of Sitwell's coat and the background are echoed in her expressionless face, as she looks down in "Zen-like" contemplation. The books to her right symbolize her role as a poet and critic in a practice that uncharacteristically looks back to Lewis's artistic forebears. Sitwell's hands are hidden, however, in a move that predicts the pair's eventual conflict. (Sitwell was notoriously proud of her slender wrists). Lewis later went on to lampoon Sitwell and her entire family in his 1930 book The Apes of God.

Art critic Laura Cumming wrote: "Lewis's portraiture has a look as distinctive as Cubism, and not unrelated, in that he fits a face together from two or three different perspectives". Art critic Michael Glover said, meanwhile, that the use of geometric lines served to dehumanize his sitter. He wrote: "in spite of the fact that the human creature under scrutiny here looks taut, pent, almost squawkily bird-like, it also looks faintly mechanised, faceted by the severity of the geometry of its lines. So if Dame Edith is indeed a bird of sorts, she is undoubtedly a mechanised bird - rather like those war planes that had so recently been menacing the skies".

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Biography of Wyndham Lewis

Childhood

Percy Wyndham Lewis was born in 1882 to Charles and Anne Lewis, an English couple who had emigrated to Nova Scotia, Canada. Charles, a wine salesman, spent much of his life travelling, leaving Anne feeling unhappy and lonely. The family moved to the UK, via Montreal and Portland (USA), when Lewis was aged just six. The Lewis's lived in Eastbourne on England's south coast, before moving to the Isle of Wight. Charles and Anne soon separated, however, and while the boy's father stayed on the Isle of Wight, Anne took her son to live with her mother in Norwood, South London.

Wyndham Lewis's biographer, Paul O'Keeffe, wrote of his time in Norwood: "Percy [he would later drop the "Percy"] played in the rolling grassy parkland surrounding the Crystal Palace under his mother's careful supervision, exchanging this, at intervals, for the heartier holiday pastimes of sea and shoreline with his father". The young artist could be willful and disobedient, however, and at the age ten he was returned from a holiday with his father with a note to Anne which warned: "Am greatly disappointed with the boy and have unpleasant misgivings about his future".

Early Training and Work

![Ernest Hemingway wrote of Lewis: “I tried to think what he reminded me of and there were various things. They were all medical except toe-jam [...] Under the black hat, when I had first seen them, the eyes had been those of an unsuccessful rapist”.](/images20/photo/photo_lewis_wyndham_1.jpg)

Lewis's artistic talent became apparent when he enrolled at Castle Hill School as a boarder. His ability in wood carving was so impressive in fact that the headmaster gave him special permission to practice his designs on the playground shed. He moved on to Rugby School at the age of 14, where he failed to make his mark academically. He preferred painting to learning, writing: "Instead of poring over my school books, there I would sit and copy an oil painting of a dog". Two years later he joined the Slade School of Art, a prestigious institution whose alumni have included CRW Nevinson, Dora Carrington and Stanley Spencer. He studied sketching and painting, but also began writing poetry. Here he rubbed shoulders with Spencer Gore - with whom he embarked upon a turbulent friendship - and became infatuated with the Welsh painter Augustus John. Lewis left the Slade under a cloud in 1901 after being caught smoking in the corridors outside the principal's office.

In 1903 Wyndham Lewis went on his first foreign excursion, visiting Spain with Spencer Gore, where he would study the Goyas hanging in the Prado. It was the beginning of an itinerant lifestyle that took him to Holland and Germany but it was in France that he was really moved when he discovered Cubism and Expressionism. He existed on cash sent by his mother, and settled in Paris, renting a room at 22 rue Delambre, where he caught lice and ended up sleeping in his studio. A note from the time also reveals that he had forgotten his age; he wrote to his mother: "Am I 22 or 23 years old? Please let me know by return of post". He began an on/off affair with a German lady called Ida Vendel, who he treated terribly, borrowing money from her as he flitted between France, Germany and England. He also suffered bouts of ill health - ranging from gonorrhea and other venereal diseases, to insomnia, depression, chest pains and general irritability.

In 1908 Lewis's literary career commenced in earnest when he began writing his first draught of Tarr, a satirical depiction of Bohemian life in Paris. The following year saw his short story "The Pole" published in the English Review. He moved back to London and in 1910 encountered Futurism while moving in the same circles as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. That same year Post-Impressionism caught the British public's eye thanks to the runaway success of an exhibition arranged by critic Roger Fry. This prompted Lewis to be more experimental with his art and this earned him some success and favorable comparisons with the continental avant-garde. He produced Cubist-inspired self-portraits as he explored the Return to Order movement (also known as Interwar Classicism) before joining the newly formed Camden Town Group, along with Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman and Walter Sickert.

Mature Period

While Lewis's artistic career began to soar, his personal life floundered. Around this time, Lewis had been having an affair with Olive Johnson a "shop-girl" and "waitress" who would give birth to two of his children, Peter in 1911 and Betty in 1913. The children were sent to live with his mother. In 1919 and 1920 he fathered two more illegitimate children who were less fortunate having been "shipped off" to a "Home for the Infants and Children of Gentlepeople".

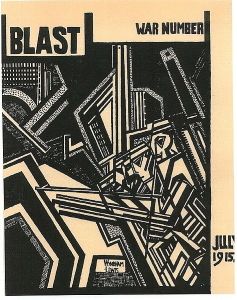

In 1912 Lewis embarked on a series of works that presented humans as robotic figures trapped in a nightmarish, mechanical world. Two years later he published the first of two issues of Blast, an aggressive journal-cum-manifesto that aimed to act as a wrecking ball on what Lewis saw as the hypocrisy and small-mindedness of Victorian Britain. This was the birth of Vorticism - since described as "Britain's only true avant-garde movement". Vorticism was given its name by the poet and playwright Ezra Pound who explained: "The Vortex is the point of maximum energy. It represents, in mechanics, the greatest efficiency". Literary historian Professor David Trotter writes; "There followed, between 1913 and 1915, the period of his most intense commitment to geometrical abstraction. Blast appeared, Vorticism arose". The manifesto was signed by eleven artists, including Pound and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, and got its name because it "blasted" the things the Vortists hated, while "blessing" the things they loved (though sometimes the same thing would appear in both lists). One passage read: "Blast France, Blast England, Blast Humour, Blast the years 1837 to 1900", followed by, "Bless England, Bless England for its ships which switchback on blue, green and red seas". Only two editions of Blast were ever produced and the Vortist movement had all-but run its course with the intervention of the First World War.

In 1914 Lewis set up the Rebel Art Centre at 38 Great Ormond Street in London, a meeting place for artists to discuss revolutionary ideas and to teach non-representational art. It's co-founder was British Painter Kate Lechmere, with whom he had an affair (and who had been the subject of his 1912 work Smiling Woman Ascending a Stair).

Lewis spent most of his life borrowing money from his mistresses, friends and his mother. By 1915 he found himself in debt to his landlord, printer, frame-maker and other creditors. The following year he enlisted in the Royal Garrison Artillery and while waiting for action his visits to brothels resulted in another bout of venereal disease. He was sent to Europe and fought at Polygon Wood and Third Battle of Ypres. He described the War as a "stupid nightmare", but denied, as his friend William Orpen had recalled, it was "hell". Lewis wrote: "It's Goya, It's Delacroix - all scooped out and very El Greco, but not hell". Lewis was luckier than most - he escaped the war unharmed and, with his mother suffering from pneumonia, was granted compassionate leave in 1917. She died three years later and his children were sent to live with their 73-year-old maternal grandmother. That year he was made Official War Artist for Canada and for Great Britain.

Lewis was a neither a good father nor a decent partner. He lived with Iris Barry between 1918 and 1921, with whom he had a daughter, Maisie Wyndham. Iris had been sent to a nursing home to have the baby while he went on holiday to Saumur with TS Eliot. The surviving correspondence between the pair is a telegram about his dinner dated from June 1920 stating simply: "PLEASE PREPARE CHOP EIGHT - LEWIS" (ergo: "please have my dinner ready for eight o'clock").

In 1920 Lewis set up Group X, a short-lived collective of British artists that aimed to provide a continuing focus for avant-garde art in post-war Britain. Lewis's dream of becoming "England's Picasso", was never realized. After the war, however, he did find noticeable success with portrait painting - producing works depicting his writer friends Edith Sitwell, Ezra Pound and T S Eliot. But he also made many enemies with art critic Laura Freeman describing him as "painter, poet, publisher and picker of fights". She added: "No target was too grand or too trivial: sentimental Victorians and the modern man of government; shark art dealers and the 'atrocious' Royal Academy; compilers of honours lists and editors of literary reviews; thin flapper girls and the fat 'Belgian bumpkins' of Peter Paul Rubens; men who read detective stories and women who liked bowl-of-apple paintings by second-rate Cézannes. People who lived in Putney". Indeed - Lewis's self-awareness was evident when he gave himself the moniker "The Enemy". He nursed a row with the Bloomsbury group for much of his life, describing Virginia Woolf as a timid "peeper" at the lives of others and he dismissed her seminal work Room of One's Own as a "highbrow feminist fairyland". It was views like this, coupled with the treatment of women in his personal relationships, that saw him labelled a misogynist. In the post war years he had become increasingly committed to his writing and published a series of books, short stories and essays on a wide range of topics including political theory, modern art, and Shakespeare. His most notorious work, however, was the satirical novel, The Apes of God (1930), which carried a blunt attack on the wealthy patrons (dilettantes) with whom he had socialized (and from whom he had even accepted commissions for portraits).

The 1930s saw Lewis begin to promote Nazism and he started to write in favor of totalitarianism. He wrote a biography of the dictator, Hitler, and described the führer as "a man of peace". He was disabused of this view seven years later on a visit to Germany when he saw the reality of Nazism, but his support of Mussolini and Franco meant that he never shook off his reputation as a fascist sympathizer. He found later success writing travel books, novels and non-fiction, and in 1930 married Gladys Anne Hoskins in a secret ceremony.

Late Period and Death

In 1937, Lewis began to lose his eyesight and the following year his portrait TS Eliot was rejected by the Royal Academy. Despite being unable to paint, he continued to write using a Dictaphone, and he entered a prolific literary period, championing art as a critic for the BBC. He also published a trilogy entitled The Human Age. He still struggled to make enough money to live, however, and between 1939 and 1945 moved to Canada in a bid to improve his fortunes.

In 1949 Lewis completed his final portrait and two years later he was struck totally blind by the pituitary tumor that had been growing in his brain. He wrote that blindness was like being "pushed into an unlighted room, the door banged and locked for ever". The tumor killed him six years later but the malignancy itself is stored, somewhat morbidly, in a cross section of his brain in a jar in London's Pathology Museum. Lewis had written more than 50 books, produced 100 paintings and more than 1,000 drawings.

The Legacy of Wyndham Lewis

For many, Lewis's personal morals and questionable beliefs have distracted from his skill as an artist. As art historian Richard Dorment wrote: "Fascistic, racist, misogynistic, homophobic, overweeningly arrogant and personally vicious: you can be all these things and still be a great artist - but I'm afraid that you are unlikely to be a great portrait painter". But the writer Will Self was a little more sympathetic writing: "Wyndham Lewis's great misfortune was to fail to produce what was indisputably one of the great Modernist works, to produce a work that people could batten on to like The Waste Land or Ulysses in literature or in painting to come up with a single defining canvas in the way that Picasso did with Guernica or even some of Paul Nash's paintings from the First World War". It is true that Lewis's name no longer carries the weight of his modernist brothers. But as Will Self observed, Lewis was "Britain's original artist - an agitator and an innovator and a radical force in 20th century art and literature". Indeed the Imperial War Museum said his work provided a template for later rebels, like David Bowie and Tracey Emin.

In socializing with modernist icons including Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, Lewis helped found Britain's first avant-garde movement and his influence in the manifesto Blast inspired the radical work of artists Edward Wadsworth, Cuthbert Hamilton, and Lawrence Atkinson. Despite the fact that most of Lewis's Vorticist work has been destroyed, burned or ruined in flooding, his reach can also be seen in the work of British Painter David Bomberg and French artist and sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska.

He also helped a new generation of British titans in his role as art critic for the BBC, where he championed the work of Francis Bacon, Barbara Hepworth and John Minton. The Glaswegian artist William McCance has named Lewis in fact as a major influence in his machine-inspired, near abstract-style portraiture. Meanwhile, the Scottish artist Robert Montgomery dedicated his Estuary Poem to Lewis; setting light to the words "Enemies of the Icebergs and the stars", a title of a play by Lewis that appeared in Blast. The work was exhibited at the end of the estuary at Shellness, where the River Thames meets the North Sea as a warning to all about unsustainable consumption. Montgomery said of Lewis: "He was one of the really important English modernists, a painter and a writer, that very rare thing in British art, a real polymath".

Influences and Connections

-

![Francisco Goya]() Francisco Goya

Francisco Goya ![Filippo Tommaso Marinetti]() Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

![Walter Sickert]() Walter Sickert

Walter Sickert- Thomas Sturge Moore

- Augustus John

- Spencer Gore

![David Bomberg]() David Bomberg

David Bomberg![Henri Gaudier-Brzeska]() Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska- William McCance

- Edward Wadsworth

- Cuthbert Hamilton

- Lawrence Atkinson

- Sturge Moore

Useful Resources on Wyndham Lewis

- Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as FascistBy Fredric Jameson

- Some Sort Of Genius: A Life of Wyndham LewisOur PickBy Paul O'Keeffe

- Wyndham Lewis: Life, War, ArtBy Richard Slocombe

- Wyndham Lewis: Painter and WriterOur PickBy Paul Edwards

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI