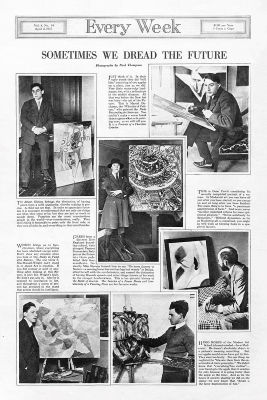

Summary of Stanton Macdonald-Wright

Best known as a co-founder of Synchromism, Stanton Macdonald-Wright was a pioneer, both as one of the first American avant-garde painters to receive international attention and for his role in introducing modern art to Los Angeles in the 1920s. He worked in both abstract and figurative styles, although both were guided by his belief in the harmonious and spiritual power of color, as well as his study of Asian art and belief systems.

Accomplishments

- As one of the founders of Synchromism (with Morgan Russell), Stanton Macdonald-Wright developed the first American modernist style of painting. His radical embrace of abstraction and reliance on color and form to create movement and meaning, places him among the pioneers of non-objective painting. Although he would eventually return to figuration, his Synchromist works were among the first completely abstract paintings of the 20th century.

- Using color to express musical qualities, Macdonald-Wright experimented with the notion of synesthesia, a popular artistic and scientific concept at the time that also featured in the work of French Symbolists, the Orphists like Robert Delaunay, and the German Expressionist Wassily Kandinsky. Creating connections between color, music, and spirituality, Macdonald-Wright was integral in developing abstraction in Paris during the 1910s, and in transmitting these experimental ideas to his colleagues in America.

- Macdonald-Wright organized the first exhibition of modern art in Los Angeles and was instrumental in fostering a community of modern artists on the West Coast. His teaching and writings on color theory were important models for young California artists, providing an alternative to New York as a cultural center. His work with the Works Progress Administration in California during the 1930s also provided training and opportunities for many.

- With new interest in his career after World War II and the development of his Neo-Synchromist style, Macdonald-Wright was a critical advocate for the relevance of early American modernist painting during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism. He was an important reminder that Modern Art had a history in America, particularly in the study of color theory.

Important Art by Stanton Macdonald-Wright

Synchromy #3

This painting, an early example of the Synchromist style, utilizes color in an abstracted manner, allowing it to serve as both the subject and theme while building a three-dimensional rhythm across the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. Macdonald-Wright described this color effect as creating "bumps and hollows," bringing the flat surface of the painting closer to a sculpture.

Here, the composition creates balance within a field of dynamic movement through the deliberate and careful juxtapositions of brilliant and repeated hues. At the same time, these patches of color create a sense of classical harmony which is reinforced by the dimensions of the square canvas. The color spirals out from a central vortex, creating a sense of outward movement similar to that of an expanding universe.

The relationship of color with music was a central idea of Synchromy. Macdonald-Wright assigned each color of a twelve-color scale to a note on the musical scale. He then composed harmonious "color chords," and gave them a sense of rhythm through the juxtaposition of the various colors and the interplay of light and shadow. The result was a painting that was not just a static image, but a dynamic interplay of color that took time to see, not unlike the performance of a piece of music. These interdisciplinary theories provide an additional layer of universalizing meaning and significance to paintings such as this, elevating them from decorative arrangements to explanations (or at least, explorations) of larger cosmic systems.

Oil on canvas

Au Café (Synchromy)

This work, which at first appears quite similar to Macdonald-Wright's earlier, purely abstract synchromies, represents his shift towards figurative images. Within the shimmering facets of color, the viewer can pick out elements to reconstruct a pair of figures: a seated man at the lower right faces a woman wearing a hat, who is raising a wine glass to her lips. After an early period of abstraction, the majority of Macdonald-Wright's mature paintings would include some level of figuration, coupled with his color theory to create suggestive atmospheres and layered meaning.

Beyond the use of color to abstract and enliven these figures, the jewel-like tones are carefully arranged to evoke feelings of happiness and liveliness. Unlike more monochromatic and static Cubist depictions of café subjects, here the viewer can easily imagine a lively café setting, filled with upbeat music and bustling crowds. The mirrored use of deep reds, juxtaposed with cool blues and greens in each figure suggests a relationship that is passionate, but also comfortable, relaxed, and familiar.

Oil on canvas - Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Oriental Synchromy in Blue-Green

Geometric planes of color (predominantly blues and greens, accented with orange and yellow) fill the canvas, creating an initial impression of an abstract composition. Yet, within the arrangement of these planes appear four human figures, obscured to the point that it is difficult to identify precisely where one figure begins and another ends. Nevertheless, the viewer is able to discern what art historian Ann Lee Morgan refers to as "fragmentary figural elements," including a face, a bent elbow, a thigh, and a raised arm. This creates a human element within the pulsating color fields.

In this particular image, sharp contrasts of light and shadow create stronger outlines toward the center of the work, diffusing toward the edges. This hazy effect not only enhances the artist's intended evocation of "space and depth," but also enhances the painting's subject - Macdonald-Wright wrote that it was "based - in its forms & arrangement & subject matter - on an opium smoking group." The graceful composition of the image reflects the euphoric, relaxed, dream-like state experienced by the opium smokers. As both Macdonald-Wright and his brother were addicted to opium during the 1910s, this would have been a personally familiar scene; shortly after this painting, however, Macdonald-Wright quit the habit, although his brother Willard never would.

Oil on canvas - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City

Synchromy in Purple

Fearing that purely abstract works could devolve into "aimless free decoration," Macdonald-Wright eventually incorporated objects into Synchromism in works such as this. This evolution also allowed Macdonald-Wright to more directly connect his painting to the Old Masters, creating an artistic pedigree for the movement. The most significant figural inspiration for both Macdonald-Wright and Russell came from the work of Michelangelo, and both artists sought to reimagine similarly powerful, muscular male figures in their works. Macdonald-Wright said about Michelangelo in a 1964 interview that "To me he was one of the greatest draftsmen who ever lived. And of course, to me, sculpture ended with him. There has been no great sculpture since Michelangelo."

The subject here is Michelangelo's Adam from the Sistine Chapel; we can see the splayed form of a reclining male nude emerging from the vibrant planes of color. In this arrangement, the figure is rendered in a fragmented manner, using color rather than outlines to define the form. Still, the viewer can recognize the torso, genitals, and legs of a crouching male figure, as well as the bottom half of his chiseled face. Macdonald-Wright casts his version in a color scale based on red-violet, adding in chords of yellow-orange and green. In his book, Treatise on Color, he claimed that this red-violet palette was about potential energy, which speaks to the narrative moment in Michelangelo's fresco. With Macdonald-Wright's emphasis on the figure's genitalia, however, he implies that his man is not just an awakening conscience, but also includes a sexual awakening.

We can see a second shift taking place within Synchromist theory in this painting, as Macdonald-Wright abandoned tertiary colors, focusing instead on using primary and secondary colors, and arranging them harmoniously to prismatic effect. Unlike much of his earlier work which relied on juxtaposing large planes of colors, here his carefully-placed sweeping strokes of color create an interplay of light and shadow that comes to delicately define the contours of the male form.

Oil on canvas - The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

History of Santa Monica and the Bay District

In this mural, Macdonald-Wright used the Synchromist principle of harmonious colorsto enliven a more traditionally rendered figurative image. Like many murals completed through the WPA, he chose a more realistic style that would please the public using this space - the city hall of Santa Monica. The image represents the history of both the city and the State of California, depicting two kneeling Native Americans, two Spanish conquistadors and a Franciscan priest. Inspired by an episode from the diary of Father Juan Crespi, a member of the 1769 Portola expedition to modern-day California, it recounts a meeting between the expedition members and Native Americans on the feast day of Saint Monica (August 27). Father Crespi commented that the droplets of the spring reminded him of the tears of Saint Monica. The story goes that the Native Americans escorted the Spanish to the freshwater spring in a gesture of warmth, welcoming, and kindness.

The mural was created using a technique that Stanton and Macdonald-Wright invented and called "Petrachrome." He later explained that while petri - chrome translates to colored stone, "it's made of concrete. It's made of a white concrete, which is then colored by oxides or colors or one thing or another, and by different kinds of ground-up colored stones all mixed together." This created a modern version of fresco painting, an ancient mural technique that was also regaining popularity as part of the 1930s mural movement.

The ambiguous pose of Native American figures has prompted 21st-century debate. While they might be bending to drink water from the stream that flows through the image, they appear to be bowing in a gesture of deference, submission, or perhaps even reverence to the colonizers. In recent years, several (unsuccessful) protests and petitions have called for the work's removal. For instance, Oscar de la Torre, founder of the Pico Youth and Family Center, calls the work "the Santa Monica Confederate flag" and "an image of Native American people bowing down to the Spaniards who came and oppressed and murdered and committed genocide in the Americas." Defenders of the mural have disagreed with this interpretation, some pointing to the artistic merit and historical importance of the work to bolster their argument. Santa Monica is not alone in grappling with the politics of these WPA murals; other communities are struggling to reconcile problematic images of American history in public spaces. Carol Lemlein, president of the Santa Monica Conservancy has stated "I think that many of us recognize that our public art collection does not necessarily reflect the diversity of the community at this point in time. But that is not a reason to tear [the mural] down but to encourage other representations of art to be established."

Crushed tile, marble and granite - Santa Monica City Hall

An Old Pond, a Frog Leaps in the Sound of Water

This later work by Macdonald-Wright comes from "Haiga," a series of twenty woodblock prints meant to accompany famous Japanese haikus. The image demonstrates his intention of synthesizing Asian culture and traditional techniques with the principles of Synchromy. Macdonald-Wright became familiar with Japanese art, poetry, and culture while visiting Japan in 1952-1953, and deepened this knowledge with his annual residencies at the Kenninji monastery in Kyoto beginning in 1958.

The haiku presented in this image is by the 17th-century poet Bashō. Without literally depicting the frog, the boldly colored series of swirling ovoid and spiral planes indicate his plunge into water, and, more importantly, evoke its sound. In this way, the viewer's visual experience is linked to an auditory memory, encouraging a more vivid and engaging response to both the poem and the print. Just as the poem prompts a mental image through minimal description, the blocks of color suggest dynamic movement through simple shapes.

Woodcut - Los Angeles Museum of Art

Biography of Stanton Macdonald-Wright

Childhood

Born to Archibald Davenport Wright and Annie van Vranken, Stanton MacDonald-Wright was named after women's rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whom his mother greatly admired. The family lived comfortably in Santa Monica, where his father ran a beachfront hotel. Archibald Wright was also an amateur artist, who encouraged Stanton's artistic talents, enrolling him in private art lessons as a young boy. His older brother, Willard Huntington Wright was an art writer and critic, who later wrote the very popular Philo Vance detective novels under the pseudonym S.S. Van Dine.

Although the family was not Catholic, the boys were sent to a local Catholic school. It was reported that whenever the nuns needed someone to do a creative project, they asked Stanton. At the age of thirteen, Stanton enrolled at the Art Students League in Los Angeles, where he spent the next two years developing his artistic skills under the tutelage of Warren T. Hedges, who himself had studied with Robert Henri. This introduced Stanton to the Ashcan School style and also emphasized the importance of integrating personal expression into artwork. In these early years, his painting style was also closely connected to California Impressionism.

Education and Early Training

In 1907, at the age of seventeen, Macdonald-Wright married Ida Wyman, a guest at his father's hotel whom he had known for two weeks. The young couple relocated to Paris, where he studied at the Sorbonne, the Académie Julian, the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Colarossi. While in Paris, Stanton moved in avant-garde art circles, meeting Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, Gertrude and Leo Stein, and fellow American student Thomas Hart Benton. As a young student, he was fascinated by color theory, most recently developed by optical scientists Michel-Eugène Chevreul, Hermann von Helmholtz, and Ogdon Rood. In particular, Chevreul's writing on "simultaneous contrast," studying how colors react to one another, would influence Macdonald-Wright.

During his studies in Paris, Macdonald-Wright met Morgan Russell, a fellow American studying art. From 1911 to 1913, the two friends studied intensely with the Canadian painter and color theory proponent, Percyval Tudor-Hart. From Tudor-Hart, they learned to see color as related to music (in fact, he directly correlated the twelve colors of the spectrum with the twelve steps of the musical scale, and used this scheme to compose visual "melodies"). The painters argued that harmonious visual compositions could be produced by selecting "color chords" that were developed from chromatic scales in which each color was assigned to a note on the musical scale. Pitch was expressed through luminosity of color, tone through hue, and intensity through saturation.

Working as a pair, Macdonald-Wright and Russell developed a movement they called Synchromism, which used color in an abstract, rather than (what they saw as restrictive) representational manner. They drew on analogies with musical composition, but combined planned intervals and chords with more intuitive combinations. By focusing on juxtaposed planes of color, contrasting to emphasize the materiality and tactility of color, they believed their paintings could directly evoke emotions and sensations. Its guiding principle was the close relationship between color and music, as MacDonald-Wright explained, "Synchromism simply means 'with color' as symphony means 'with sound.' Their first exhibition as Synchromists took place in June 1913 in Munich.

Macdonald-Wright and Russell correlated particular colors with particular emotions, for instance, as Macdonald-Wright once explained, "Yellow-Orange has also a braggart tendency but at bottom it is weak and sickly. It is like the last pretenses dying in a pompous soul. On this account it has a quasi-sad note, like an old man who feels senility to be not far off." Although the Synchromists aimed to emphasize color itself as both subject and theme, not all of their works were purely abstract. Macdonald-Wright experimented with representing more figurative subjects (often the ideal male form), but in an abstracted, nearly-cubist faceted manner, whereas Russell's works tended to be more purely abstract.

The Romanticist painter Eugène Delacroix's writing on color, particularly his work with complementary colors was critical to the development of Synchromism. Aside from color theory, Macdonald-Wright was inspired by Paul Cézanne, who he believed had used color in a more structural (rather than decorative) fashion. He owned four watercolors by Cézanne and had experimented with his Post-Impressionist style. He was also deeply interested in the landscapes of J.M.W. Turner, who he credited with having "removed all the gross materialism out of objects and has given me the essence of the beautiful."

Relying on color, Synchromism bridged elements of Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism, and German Expressionism. Indeed, the relationships between color, music, and sensation were themes common in early 20th-century abstraction. While Synchromism was one of the earliest to develop, it was commonly dismissed by other abstract artists as having merely borrowed the principles of Orphism or Cubism. Macdonald-Wright adamantly denied these influences, although their grandiose language might have contributed to the critics' hostility. In their writings, Macdonald-Wright and Russell aimed to differentiate Synchromism from other similar movements, explaining in exhibition catalogues that they rejected the "brown and white of the Cubists" in favor of using "gradations of color" to express "the depth of space," and also calling Futurism "superficial" and "of secondary interest." They similarly dismissed Orphism as flat, weightless, and too decorative.

At the start of WWI, Macdonald-Wright and his brother Willard Huntington Wright (who had been working as an author and editor) moved to London, where they lived for the next two years. During this time, the brothers collaborated on three art books that would later be published in New York. The most famous, Modern Painting: Its Tendency and Meaning (1915), provided an overview of major modernist art movements which predicted the forthcoming domination of abstraction over realism (simultaneously championing Synchromism). During these same years, however, Macdonald-Wright began reintroducing figurative elements into his paintings, often referencing a Greco-Roman tradition. This reflected a general trend during the war, when many artists embraced the classical past both as an escape from present-day turmoil and as a historical connection that extended beyond modern politics.

In 1915, Macdonald-Wright moved to New York, where he lived with Thomas Hart Benton and attempted to gain recognition with American audiences. In 1916 he participated in the Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters (organized by his brother), and in 1917 he had his first solo exhibition at Alfred Stieglitz's 291 Gallery. Unfortunately, despite this mild success, he did not reach the level of fame he had been hoping for, and struggled to make ends meet financially. Towards the end of his time in New York, he taught painting lessons to young women in order to earn money and created posters and illustrations (often working under the pseudonym "d'Este." Meanwhile, Morgan Russell turned away from the Synchromist style in 1916.

Mature Period

In 1918, Macdonald-Wright decided to move to Los Angeles, to see if he might have better success there. In 1920, with the support of Alfred Stieglitz, he organized "The Exhibition of American Modernists," the first show of modern art in Los Angeles. Held at the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art, the exhibition included several of his own "synchromies" as well as pieces by John Marin, Arthur Dove, and Marsden Hartley. Although the show received good press and had decent attendance, sales were slow.

Shortly after this exhibition, Macdonald-Wright decided he was dissatisfied with the "sterile artistic formulism" of modern art, and even found that Synchromism felt stale and academic. He thus abandoned the style from 1921 (to revisit it in 1953). From 1922 to 1930, he served as the director of the Los Angeles Art Students League, where he emphasized drawing from live models instead of traditional plaster casts, and redesigned the school's curriculum based on "intelligent drawing." In 1924 he published the textbook, Treatise on Color, in a limited-edition series of 60 copies, mostly intended for his students. Through reproductions and circulated copies, this book would have an outsized impact on the development of color-based abstract painting.

During the 1920s, he expanded his studies of Eastern art and culture, which had first started in Paris during 1912. In addition to art, philosophy, and literature, he began learning the Chinese language and wrote four Chinese-themed plays for the Santa Monica Theater Guild, where he also served as the director, set designer, and actor. He integrated this into his esoteric paintings, arguing that "Western philosophy has tried to solve the universal mystery by means of finding an absolute rather than accepting, as the Chinese have, the mystery as fait accompli."

Under the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), that was a pilot for the larger Works Progress Administration (WPA) employing artists during the Great Depression, Macdonald-Wright was selected to paint a series of murals for the Santa Monica Library. His ambitious scheme, depicting the development of mankind, was completed in 18 months, during which Macdonald-Wright reallocated his own salary to pay other struggling artists. Then, beginning in 1935, he served as the Director of the Southern California division of the WPA, as well as WPA Technical Advisor for seven western states. During the next seven years, he oversaw the work of WPA artists, and personally completed several important projects.

From 1942 to 1952, Macdonald-Wright taught courses on art history, Oriental aesthetics, and iconography at UCLA, USC, Scripps College, and the University of Hawaii. In 1952 and 1953, he traveled to Japan as a Fulbright exchange professor and lectured at Kyoiku Daigaku (the Tokyo University of Education).

Late Period

In 1954, Macdonald-Wright retired from teaching, and returned his focus to abstract painting, producing an impressive body of "neo-synchromist" work. He continued to experiment with elements of Eastern art in these works, integrating them with the elements and principles of Synchomism. MacDonald-Wright later reflected on this artistic reawakening, stating that "At first I saw my new painting with a certain astonishment, for I had made the 'great circle,' coming back after 35 years to an art that was, superficially, not unlike the canvases of my youth. However, at bottom there was a great difference: I had achieved an interior realism, what is called yugen by the Japanese. This is a sense of reality which cannot be seen but which is evident by feeling, and I am certain that this quality of hidden reality was what I felt to be lacking in my younger days." Notably, the renowned Alfred Barr, Jr., the American art historian and the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, agreed that these Neo-Synchromist painting surpassed MacDonald-Wright's earlier works by carrying a stronger sense of luminosity and "a deeper spirituality."

Beginning in 1958, Macdonald-Wright spent five months of each year living at the Zen monastery of Kenninji, in central Kyoto, where he learned more about Japanese art and poetry, and did a great deal of his painting. The following year, in 1959, MacDonald-Wright completed his Synchome Kineidoscope, a project he had envisaged with Russell decades earlier. The structure was designed to "make a painting exist and change through a period of time." He intended it to be a synthesis of artistic media, unifying the arts by incorporating color, light, sound, movement, and time.

These years witnessed a resurgence of interest in Macdonald-Wright's color painting. He was the subject of retrospectives at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1956, at the Smithsonian National Collection of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C. in 1967, and at the Art Galleries of UCLA in 1970. There was also a brief revival of interest in Synchromism, with the Whitney Museum of American Art organizing "Synchromism and American Color Abstraction: 1910-1925" in 1978-1979, a six-museum travelling exhibition of earlier Synchromist works.

Stanton Macdonald-Wright passed away at his home in Pacific Palisades, California, at the age of eighty-three.

The Legacy of Stanton Macdonald-Wright

Although Synchromism was not a commercial success in the 1910s, it was an early conduit of modernist abstraction in America. It also introduced new color theory and musicality from Europe, influencing avant-garde artists in New York and Los Angeles. American artist Georgia O'Keeffe was a proponent of Synchromism, describing some of Macdonald-Wright's paintings in 1916 as "Theory plus feeling - They are really great." Robert Henri called Macdonald-Wright "the greatest master of color in painting that ever lived."

Macdonald-Wright had significant influence on the development of American abstraction. Artists who adopted some of the principles of Synchromism in their work include Russian-American painter Jules Olitski, whose Color Field paintings aimed to present pure color's power to evoke strong emotions, painter Stuart Davis, who used color chords arranged in geometric compositions to visually convey the musical qualities of jazz music, as well as American artists Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Dasburg, who experimented with Synchromism and aimed to link color and music in their works. Curator Marilyn Kushner also notes that Synchromist ideas can be seen in Joseph Stella's spectrums-filled paintings as well as in the works of Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Alfred Maurer, and O'Keeffe.

Moreover, Macdonald-Wright also had a considerable impact through his teaching and administrative activities. In particular, his Treatise on Color (1924) influenced later teaching, perhaps trickling through the generations to impact Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock. Working for the WPA, Macdonald-Wright provided an important source of income for a generation of artists, but also advocated for the program to support styles other than American Regionalism.

Macdonald-Wright's Neo-synchromist paintings of the post-World War II era provided a direct connection from contemporary abstraction, including Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, to the beginnings of twentieth-century American abstraction. He was essential in connecting the legacy of earlier abstract painters to the practices of the 1950s and 1960s.

More generally, Macdonald-Wright brought abstract art to public attention through his organization of Synchromist exhibitions outside of New York, including the first Modern Art exhibition to ever take place in Los Angeles. Christopher Knight, writer and art critic for the Los Angeles Times, has declared "It simply isn't possible to understand 20th century art in L.A. without understanding Macdonald-Wright's work and career."

Influences and Connections

-

![Eugène Delacroix]() Eugène Delacroix

Eugène Delacroix -

![Paul Cézanne]() Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne - Percyval Tudor-Hart

-

![Henri Matisse]() Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse -

![Auguste Rodin]() Auguste Rodin

Auguste Rodin ![Morgan Russell]() Morgan Russell

Morgan Russell

-

![Thomas Hart Benton]() Thomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton -

![Stuart Davis]() Stuart Davis

Stuart Davis -

![Alfred Maurer]() Alfred Maurer

Alfred Maurer -

![Arthur Dove]() Arthur Dove

Arthur Dove - Andrew Dasburg

-

![Thomas Hart Benton]() Thomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton ![Morgan Russell]() Morgan Russell

Morgan Russell

Useful Resources on Stanton Macdonald-Wright

- Synchromism and American Color Abstraction, 1910-1925By Gail Levin

- Synchromism and Color Principles in American Painting, 1910-1930By William C. Agee

- The Art of Stanton MacDonald-WrightBy Stanton MacDonald-Wright

- A Treatise on ColorOur PickBy Stanton MacDonald-Wright

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI