Summary of Andrea Mantegna

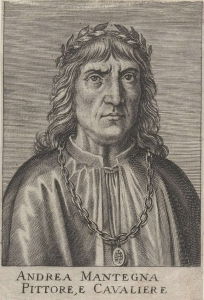

Andrea Mantegna's productive years, 1448-1506, bridged the Early and High Renaissance periods, and the spirit of his work exemplifies the vexed contrasts between humanism and martial aggression, between piety and the profit motive, which characterized the era. In particular, few bodies of work sum up the simultaneous emphasis placed on classical military valor and Christian piety during the Italian Quattrocento (fifteenth century) as perfectly as Mantegna's. Strongly influenced by Classical Art, his paintings pay equal homage to Roman imperial rulers and Christian saints, while in formal and stylistic terms they exude a complementary combination of chiaroscuro hardness and soft, naturalistic delicacy.

Accomplishments

- Mantegna was a pioneer of spatial illusionism, using virtuosic effects of visual distortion to generate uncanny impressions of three-dimensional depth within two-dimensional surfaces. This was used to most engaging and playful effect in his frescoes, which could give the impression of a window opening out onto the interior of a classical palace, or a sky filled with heavenly bodies and mythological figures.

- A committed antiquarian and amateur archeologist, Mantegna's engrossment with classical culture informed his approach to representing contemporary secular and religious themes. Christian saints exhibit the rippling musculature and contrapposto elegance of ancient Greek statues, while the Virgin Mary appears in the partial guise of a pagan fertility God. These motifs embody the contrast between imperial military ambition and Christian theology that embodied the Italian city-state cultures of the period.

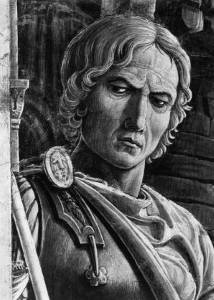

- Mantegna was a proponent of humanism, empowered by the intellectually adventurous city cultures of Padua and Mantua, the former his birthplace, the latter his home under the patronage of the Gonzaga family. His works express a searching and morally ambivalent interest in the human mind and heart, none more so than his sharply drawn self-portraits. These give the impression of a searching intellectual spirit unburdened by moral compunction and stale theology, with a piercing stare set beneath a rocky, furrowed brow.

- Mantegna brought the sharpness of chiseled stone to his portraiture, using pale skin tones and deep lines of shadow to emphasize the sharp edges of the body: its muscle and sinew. His close connection to the Bellini family - father Jacopo, sons Gentile and Giovanni Bellini, both painters like their father, and daughter Nicolosia, whom Mantegna married - influenced this classically informed approach. At the same time, Mantegna was influenced by the softer color palettes of Giovanni Bellini's work, which he emulated to offset the sculptural and architectonic qualities of his painting.

Important Art by Andrea Mantegna

San Zeno Altarpiece

This altarpiece depicts six separate scenes, central amongst them the sacra conversazione, in which saints surround the Madonna and Child. The bottom three panels present, from left to right, the agony in the garden, the crucifixion, and the resurrection. The frame of the altarpiece mimics the facade of an ancient Greek temple, painted gold, with the illustrations framed by Corinthian-style pillars. The scene is thus positioned, as it were, within the space of the temple, with the illusion of the pillars receding behind the frame. The backgrounds of the panels are also decorated to suggest the interior of the temple. The dominant colors used are red and gold, with hints of green, forming a tonally harmonious scene orientated around the central figures of holy mother and child, who meet the viewer's gaze as the peripheral figures stare in various opposing directions.

The work offers a kind of stylistic synthesis typical of Mantegna's approach, utilizing a classical style of portraiture to portray Christian themes and characters, who carry themselves in the manner of Greco-Roman icons. This is clearest in the case of Saint John the Baptist (top right) who stands in a classical contrapposto pose like Polykleitos's Doryphoros, the spear-bearer. Mantegna repurposes these and other classical formal elements to give Christian narrative a new life and vigor, as in the three lower scenes, which present in linear order the events of the death and resurrection of Christ. A sense of narrative continuity is generated, for example, by the awakening in the bottom-right panel of the sleeping figures from the 'agony' scene. Such thematic motifs allowed (potentially illiterate viewers) to connect emotionally to the events of Christ's life via engagement with the altarpiece.

The spatial organization of the piece is also metaphorically significant, with events in the mortal world positioned below the palace of the deities in the top three panels. This technique is also common in classical art, with deities often placed above human actors in frescoes to signify the distinction between the mortal and immortal worlds. A similar formal approach - using panel divisions to separate out different orders of existence - had also become widespread during the fourteenth century, with Madonna and child often featured in the central panel and saints radiating outwards. Mantegna modernizes this technique, however, by unifying the imaginative space depicted across rows of panels, once again demonstrating his capacity to renew time-honored formal techniques and thematic motifs. He also contrasts Pagan antiquity with the Christian present by offsetting the vibrant colors of the Christian outfits against the muted colors of the temple behind. This contrast serves to acknowledge the influence of the classical framework on Renaissance culture and art while suggesting their repurposing for modern times.

Tempera on panel - Basilica di San Zeno, Verona, Italy

Di sotto in su

One of Mantegna's most famous works, the ceiling panel of the Camera degli Sposi, or "bridal chamber" in the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua was commissioned by Ludovico III Gonzaga, who employed Mantegna for a number of years. The work creates the illusion of a circular window opening onto the sky above. The bridal chamber below is decorated to suggest a ceremonial pavilion, the walls painted with elaborate architectonic decorations. The oculus is painted to look like marble, and is surrounded by a garland. The illustrations give the impression from below of figures gazing down into the oculus, while winged cherubs gather in and around it, the two halves of the opening demarcated by a peacock and potted plant. The figures seem to be conversing with each other while looking down from the cloud-flecked sky. The type of optical illusion utilized in the ceiling panel is called di sotto in su, meaning "foreshortening", in this case generating the impression of bodies and forms glimpsed from directly below. The illusion of three-dimensional space is complemented by the hyper-realistic style of the decorations around the oculus, which suggest an internal architectural space different to the actual architectural space of the chamber.

Like Mantegna's earlier altarpiece, the work infuses elements of classical style with Renaissance Christian themes. The imaginary pavilion is decorated in high Greco-Roman style, with classical portraits on the ceiling, while the use of architectonic wall-decoration in and of itself harks back to the decoration of tombs during the classical era as 'rooms for the dead'. The inclusion of the cherub, meanwhile, pays homage to the Eros of the classical pantheon while also being an example of the putti (naked cherubs or children) common in Renaissance religious art (as was the peacock).

In spite of these grand allusions, the piece has a feel of playful lightheartedness, as the figures stare down into the oculus - as if breaking the fourth wall of the performance space - or interact with one another in curiosity. Looking closely, we can see that the potted plant is supported by a pole crossing the oculus, and the woman on the top left has her hand on the pole as if she is about to play a prank by dropping the plant into the courtyard below. Cherubs are also known for their playfulness and trickery, and the presence of so many gathered around probably means that some sort of antics are afoot.

In practical terms, the ceiling oculus of the Palazzo Ducale was probably intended to exalt the Gonzaga family by suggesting that their lives were of interest to the heavenly throng gathered above. In retrospect, it has turned out to be one of Mantegna's most enduringly influential works. The first noted example of the use of di sotto in su perspective painting, it marks a significant leap forward in the evolution of spatial illusionism. The technique was reiterated in numerous Baroque and Renaissance structures, and became a defining characteristic of the fresco art of Antonio da Correggio, Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Andrea Pozzo, and others.

Fresco painting on panel - Palazzo Ducale, Mantua, Italy

Saint Sebastian

This is one of three famous representations of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian created by Mantegna. Sebastian is tied to the ruins of a Corinthian column, pierced with numerous arrows. Behind him are a profusion of Roman ruins, while to the bottom right two grim assassins stand with a quiver of arrows (interestingly, the man holding the arrows is rumored to represent Mantegna himself, a curious sort of self-homage). The color scheme of the painting primarily consists of light browns and skin tones, with a light blue background.

Iconographic images and worship of the martyr Saint Sebastian - reputedly killed during the anti-Christian purges of the Roman emperor Diocletian but brought back to life by Saint Irene - were common during the fifteenth century. However, Mantegna diverged from traditional representations of the saint through numerous references to antique landscapes and architecture (again, an ironic homage given the identity of Sebastian's killers). He further references the ancient heritage of Renaissance painting and sculpture with his use of the classical contrapposto pose, and idealized musculature and physique, to represent Saint Sebastian's body, alike that of Greek statuary. The scene of a saint pierced with arrows also became a metaphor for the Black Death during the medieval era, for which reason Saint Sebastian became a patron saint of plague victims. The image of a ravaged body resonated with the Italian citizens of the fourteenth century, when the Black Death peaked in Europe, and Saint Sebastian remained an icon for centuries to come.

From a modern perspective, what is perhaps most notable about Mantegna's representation of Saint Sebastian is its erotic quality. He portrays him in minimal clothing, with a sharply articulated physique. The penetration of his skin with arrows also has clear sexual overtones, while his facial expression seems to occupy the cusp of pain and pleasure, adumbrating Sebastian's later identification as both a gay icon and a figure of masochism. Many of the numerous modern interpretations of his death have been highly sexualized, such as Derek Jarman's in Sebastiane, a pioneering film in the representation of male homosexuality. Mantegna's portrayal stands subtly in the background of this tradition.

Tempera on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

The Triumphs of Caesar frescoes

This series of nine frescoes depicts the march of Caesar back to Rome after a military victory, a segmented, panoramic representation of the procession with Caesar's chariot depicted at the rear. The sequence is full of unabashed, almost amoral images of Roman triumph: victorious soldiers, plundered riches, burnished armor, elephants and standards, set against a backdrop of sacked cities. However, the fresco seems to offer a synthetic portrayal of Roman conquest in general rather than representing a particular war or campaign. It begins with The Picture Bearers, followed by The Standard Bearers and Siege, the Bearers of Trophies and Bullion, The Vase Bearers, The Elephants, The Corselet Bearers, The Captives, The Musicians, and finally Caesar on his Chariot. While presenting a cohesive whole, each of the frescoes is thematically autonomous within the lens of victory.

Once again, this seminal work of Mantegna's offers an audacious combination of classical and Renaissance Christian themes and motifs. And again, Mantegna's self-compelled interest in classical subject-matter also seems to stand for a broader cultural climate, in this case the fascination in late fifteenth-century Mantua and Renaissance Italy more generally with the Roman military triumph. Francesco II Gonzaga was a successful soldier, who also made money from leasing out the services of mercenary armies. Mantua was also the birthplace of Virgil, the first-century BC poet who wrote the famed propagandic epic about the birth of Rome, the Aeneid. It is perhaps unsurprising then, that the Gonzaga family - the rulers of Mantegna's Mantua - felt a certain affinity for the military autocrats of the early Roman imperium. Through the lens of Mantegna's historical imagination, Francesco II's military victories could be compared to Roman imperial conquests, and Francesco, therefore, to Caesar. At the same time, certain aspects of the work do not faithfully mirror qualities associated with the Roman military. In the later Italian Renaissance, this piece was extremely influential for its representation of ancient Rome, hailed by Giorgio Vasari as Mantegna's best work. Artists such as Andrea Aspertini and Hans Holbein the Younger made prints of the piece, and Peter Paul Rubens referenced it in his Roman Triumph (1630).

From a modern perspective, this work is interesting for the ambivalent qualities associated with the aftermath of victory. Part of the procession appears to be made up of civilians, while the soldiers themselves are not presented in coordinated uniform, and the units appear somewhat disheveled and disorganized, perhaps flushed with victory and alcohol. The stacked armor in The Bearers of Trophies and Bullion seems precarious, as if it were about to spill over, while the uniforms do not appear to match each other, or the armor worn by the soldiers. It is as if foreign victory were masking internal disorder and incoherence. The rear end of the fresco, meanwhile, unfolds a marked emotional shift. Caesar's head is slightly downturned, while the surrounding figures appear almost lethargic, as if weighed down with bloodshed. Mantegna thus offers a more double-edged image of military conquest and imperial ambition - both in the classical and Renaissance periods - than the official function of this work might suggest.

Tempera on canvas - Hampton Court Palace, London

Madonna of Victory

This altarpiece portrays a man reputed to be Francesco II Gonzaga in adoration of the Madonna and Child. Opposite Francesco is Saint John the Baptist, who holds a cross and a cartouche with a Latin inscription. His mother, Saint Elizabeth, the protector of Francesco II's wife Isabella d'Este, is also present, wearing a yellow turban. Saint Michael, Saint Longinus, Saint Andrew and Saint George are lined up to the sides of the Madonna and infant Jesus. The Virgin sits on a throne inscribed with the phrase REGINA/CELI LET ALLELVIA, meaning "Queen of Heaven, rejoice, Hallelujah." The baby Jesus holds red flowers, while circling around and behind them is an arch strewn with leaves and fruits, with a shell and red coral centerpiece.

This lush work presents Madonna as both the queen of fertility and an icon of purity, offering a typical synthesis of classical pagan and Renaissance Christian ideals. The fruit, coral, and abundance of greenery around the arch stand for life, nature, and fecundity. Fruit had also connoted the cycle of the seasons since ancient times, both for obvious reasons and because of its connection to the myth of Persephone and the pomegranate. (Hades had tricked Persephone into eating pomegranate seeds while she was his captive in the underworld, binding her to remain below the earth for part of the year, thus creating the winter months during her absences.) At the same time, fruit has traditionally refered to purity, in particular melons, an image strongly related to the rituals of cleansing in Christian ceremony. The presence of the apples nuances the work's thematic scope further, representing not only fertility but also temptation and the fall, through its connection to the story of Adam and Eve. This may subtly position Madonna and child as Adam and Eve, a theory reinforced by the presentation of Saint Elizabeth as a patron Jewess with a yellow turban.

This work was commissioned to mark a recent victory over the French, but it also more subtly conveys the Mantuan attitude towards the Jewish religion during the fifteenth century. A Jewish doctor named Daniele da Norsa, a subject of the Gonzagas, had recently removed the obligatory icon of the Madonna from his home and replaced it with another, less Marian image. This was widely regarded as blasphemy, and as punishment Da Norsa was forced to pay 110 ducats towards the commission for Mantegna's Madonna of Victory. This subtext of the work is hinted at by the unusual presentation of Saint Elizabeth, but is complicated by the presence of Francesco II Gonzaga himself as the faithful supplicant. By positioning Francesco in a painting in which a qualified Jewish presence is allowed alongside the Christian, Mantegna - at his ruler's behest, perhaps - suggests both the Gonzagas' tolerance of, but also ultimate dominion over, the Mantuan Jews. It may also position Judaism as an internal threat to Mantuan stability similar to the external threat presented by the French. This topical subtext is typical of the way in which art, even 'great' art, can become entangled in the politics and propaganda of its era.

Tempera on canvas - Louvre Museum, Paris

Adoration of the Magi

This image has a relatively simple composition as compared to many of Mantegna's works, setting the busts of five figures around the baby Jesus, set against a completely dark background. To the left, Mary holds up the newborn Christ, a subject of adoration for the "magi" or wise men to the right. The magi hold gifts of incense and gold for the infant as they kneel before him. The painting offers a more intimate, close-up representation of its subject-matter than others by Mantegna, and an unusually vibrant color palette.

The story of the birth of Jesus, representing both the origins of Christianity and a more general theme of salvation, was a very potent one in Renaissance culture and art, and there were numerous representations of this scene which predate Mantegna's. However, Mantegna's is unusual in its allusions to alien and exotic cultures, references which were significant in Mantua at the turn of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries given the presence in the city-state of a Jewish population that was often scapegoated and ostracized. The three wise men - who in the original story have travelled from 'the East' - have darker skin tones than the pale and rosy-cheeked infant and virgin. The color variation in the clothing of the magi adds to their exotic characterization, with Mary and Jesus offset by paler dress.

These images of racial variation - like the age differences between the magi - may suggest the unifying quality of salvation. The baby Jesus thus acts as a sort of priest to the visiting sages, raising his hand as if sanctifying each with his blessings. Through such details, we may feel from a contemporary perspective that Mantegna is suggesting both the personal and the universal nature of spiritual redemption. The close-up perspective of the work enhances the impression of a series of individual experiences bound by the overall quality of salvation, as do the differently oriented body positions of the Magi. The unusual perspective also seems to place us in the company of the group, as if we do, can partake in the scene of devotion.

Distemper on linen - Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Biography of Andrea Mantegna

Childhood

Andrea Mantegna was born in Isola di Carturo, near Padua in the Republic of Venice, in modern-day Italy. His father Biagio was a poor carpenter, and as a young boy Mantegna learned sheep-tending and other rural agricultural tasks. Biagio died when Andrea was young, and in 1442, at the age of seven, he became the apprentice and adoptive son of the Paduan painter Francesco Squarcione. Three years later, at the age of just ten, Mantegna was accepted into the Fraglia dei Pittori e Coffanari, the Paduan Artists' Guild.

Squarcione had adopted other young painters who went on to achieve fame, though he himself never enjoyed a stellar career. He was known primarily for his enormous collection of Greco-Roman antiquities and for his successful training establishment, which taught young artists to copy the antique style, and which earned him the title of 'Father of Painting.' Mantegna's enthusiasm for classical antiques and the classical style stayed with him all his life, but he became displeased by the shady legal status of Squarcione's practices, and ultimately brought charges of fraud and exploitation against the older artist, arguing that Squarcione had drawn profits from his work without providing promised compensation. A court ruled in his favor in 1448, releasing Mantegna from Squarcione's influence.

Early Years

The culture of Renaissance Padua was very formative for Mantegna. On a par with Florence in its commitment to Renaissance Humanism and intellectual endeavor, it provided an environment devoted to the reproduction of classical ideals and civilization. Mantegna's classical interests were nurtured in this setting. He was also highly influenced in his early years by the great painter Jacopo Bellini, whose classical approach to form and anatomy is often likened to Mantegna's. Even more significant was the influence of Donatello, who forged a unique Greco-Roman-influenced style with pagan thematic overtones. The spiritual quality of Donatello's work, and its impression of harmony between the mind, soul, and body, moved Mantegna deeply, and he drew extensively from these traits in his own work.

Mantegna emerged as a more-or-less fully-fledged painter at the age of seventeen. He was already well-regarded enough in 1448 to start receiving commissions, the first recorded of which was for the altarpiece of Madonna at the Church of Santa Sofia in Padua. Now destroyed, the altarpiece was described by the sixteenth-century painter Giorgio Vasari as exhibiting the technical skill of "an experienced old man."

In 1449 Mantegna began creating several frescoes for the Ovetari Chapel in the Eremitani Church in Padua, working in collaboration with Niccolò Pizzolo, another student of Squarcione. This project, however, signaled the demise of the partnership between Mantegna and Pizzolo, who subsequently died in a brawl, leaving Mantegna in charge of the remaining decoration of the chapel during 1453-56. While working on the Ovetari Chapel Mantegna also grew closer to the Bellini family, marrying Nicolosia Bellini in 1453 at the request of her father Jacopo. The couple had four sons, two of whom, Lodovico and Francesco, survived into adulthood, and a daughter, Taddea. Through his marriage Mantegna also gained two influential brothers-in-law, the painters Gentile and Giovanni Bellini. Of the two, Giovanni was a greater influence on Mantegna's work, teaching him to soften his color-palette and style.

The influence of Mantegna's father-in-law Bellini fostered a keen interest in conveying the personality of artistic figures. This is most evident in Mantegna's dynamic and powerful portraits. Foremost in this category is the self-portrait included in the Eremitani frescoes, recognizable for its sharply defined expression and deep facial lines, conveying an impression of great emotional intensity and gravitas. The frescoes also demonstrated Mantegna's mastery of landscape painting, characterized by painstaking attention to decoration and detail. The Eremitani frescoes won Mantegna fame and reverence throughout Padua. His combination of classical technique and rigor with the softer approach to characterization he had learned from Giovanni Bellini generated works of brilliant subtlety and beauty. Mantegna was appointed chief of the school of Padua, where he gained numerous disciples, and was employed to create portraits of scholars. He also worked on several prestigious commissions across Italy, burnishing his reputation.

Mature Period

Mantegna's finely honed skills and stellar reputation caught the attention of Ludovico III of the House of Gonzaga, the Marquis of Mantua and one of Italy's most powerful city-state rulers. In 1457 Ludovico sent an offer of patronage to Mantegna, but the artist was slow to respond, keen to remain in Padua, a city which catered to his educated tastes. Ludovico III sent numerous further offers, each increasing in compensation, and promised living quarters and food for Mantegna's family. The artist continued to demur to the Marquis's advances but eventually accepted, moving to Mantua in 1459.

While working for the Gonzaga family Mantegna was free to explore his classical interests. Ludovico III and his descendants were renowned humanists, hosting intellectuals and artists at their court such as Alberti and Brunelleschi, and also the Medici family of art patrons.

Mantegna took up amateur archaeology in 1464, embarking on group excavations to look for Roman inscriptions. These events were part-historical reconstruction, the participants wearing costumes and assuming roles from the Roman period. Mantegna also collected numerous antiquities for his living quarters. His zeal for antiques and archiving filtered into the work he produced in Mantua, which incorporated numerous classical references and motifs.

Ludovico paid Mantegna 15 ducats a month, allowing him to travel regularly, though he was also employed on various ongoing commissions. The Marquis was patient of Mantegna's methodical working process, although the artist often complained of his working conditions and ongoing ailments, and his argumentative nature led to conflict with Ludovico's employers. This characteristic was exemplified by a dispute with the foreign engraver Simone di Ardizone. Mantegna had begun working with Ardizone on a printing plate but discovered that Ardizone was simultaneously working with another artist in Mantua. Infuriated, Mantegna had Ardizone and the other artist attacked, then had Ardizone banished from Mantua on charges of sodomy. In 1476, Mantegna claimed that the conditions of his employment had not been met, and that he and his family had been forced to live in hardship. In response Ludovico III constructed a house for Mantegna which he filled with antiquities.

In 1478 Ludovico fell victim to the plague, and Federico Gonzaga became the new head of the household. Six years later, Francesco II took over the family. Mantegna continued to work for the House of Gonzaga, producing various artworks for Francesco. He famously completed his Triumphs of Caesar (1484-92) for a room designed as a theatrical performance space. This work constitutes a stunning visual index of Mantegna's intellectual and creative interests, including his knowledge of humanism and archaeology; the references embedded in the work also bring together a plethora of significant biographical influences on Mantegna. He also completed a range of religious works during his mature period, including a commission for the Pope during 1488-90, as a result of which he returned to Mantua with the title of Count Palatine. At some point in the 1480s, Mantegna was knighted, and in 1492 he settled permanently in Mantua.

Late Period

Mantegna's later works are characterized by a fascination with the elegance and optimism of youth. While he declined physically, and his financial fortunes declined - perhaps reflecting his tendency to fall out with his patrons and peers - he seemed to embrace life's joys all the more fervently, painting scenes of military victory and spiritual epiphany. These qualities can be sensed in Parnassus (1495-97), which portrays the virtues of pagan culture, and Madonna of Victory (1495), which immortalizes one of the successful battles of Francesco II. However, the Marchioness Isabella d'Este, princess and wife of Francesco, was not taken with Mantegna's portrait of her, which employed a more realistic approach than she was comfortable with, at odds with the tradition of physical idealization of monarchy.

The last years of Mantegna's life were not as comfortable as his paintings might suggest, partly due to financial concerns and partly due to the behavior of his eldest son, Francesco. Francesco was frequently in trouble with the Marquis, and was eventually banished from the Gonzaga Court, though Mantegna's other son Lodovico remained in high regard. After the death of his wife, Mantegna bore an illegitimate son named Gian-Andrea. In 1504 the ageing artist drew up a will, which unsurprisingly favored Lodovico, but more surprisingly favored Gian-Andrea over Francesco. In 1504, Mantegna requested that he be able to purchase a chapel in the Basilica of Sant'Andrea, Mantua in which to be buried, a request which was granted. Although his health waned, his vigorous spirit remained, and he continued to work until the end of his life. He died on September 13th, 1506, at the age of 74, in his home in Via Unicorno, amongst his collection of antiquities.

The Legacy of Andrea Mantegna

Mantegna's enthusiasm for the classical style provided a framework for generations of later Italian Renaissance artists. The use of allusions to the style and themes of Classical Art became a prominent feature of other artists' work, and the idealized standard of beauty which he favored became dominant in painting and sculpture of the next 100 years. Leonardo da Vinci drew on Mantegna's realistic approach in his paintings, while the German painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer, a key figure in the Northern Renaissance, was also influenced by Mantegna's advances in naturalistic representation.

Even more influential was Mantegna's use of spatial illusionism, particularly in his frescoes. His interior frescoes were so accurate in their depiction of architectural interiors and landscapes that they created an enveloping illusion of three-dimensional space. These spaces often featured figures from myth or religion, allowing the viewer to feel as if they were crossing a threshold into the realm of the supernatural. Mantegna's ceiling oculus fresco in Camera degli Sposi (1465-74) is particularly notable for its depiction of the sky, as if the oculus truly led to the outside world, but a world populated by fantastical creatures. Spatial illusionism became an omnipresent feature of frescoes and ceiling-paintings in Renaissance and Baroque palaces. Examples of illusionism during these two epochs, preceded by Mantegna's work, include Antonio da Correggio's Assumption of the Virgin (1526-30), Giovanni Battista Gaulli's Triumph of the Name of Jesus (1678-79) and Andrea Pozzo's Glorification of Saint Ignatius (1691-94).

Influences and Connections

-

![Peter Paul Rubens]() Peter Paul Rubens

Peter Paul Rubens - Antonio da Correggio

- Giovanni Battista Gaulli

- Andrea Pozzo

Useful Resources on Andrea Mantegna

- Great Masters in Painting and SculptureEdited by G. C. Williamson

- Andrea MantegnaBy Maud Cruttwell

- Andrea Mantegna: Making Art HistoryOur PickBy Stephen J. Campbell

- The Genius of Andrea Mantegna (Metropolitan Museum of Art)Our PickBy Keith Christiansen

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI