Summary of Robert Mapplethorpe

There are few photographers who have sparked national debate around artistic freedom and eroticism as profoundly as Robert Mapplethorpe. Although championed for his erotic black and white photography of fetish and leather gay imagery in New York City, his artistic accomplishments range across many media. He is best known as a photographer and his subjects consisted of sculptural nudes, erotic S&M imagery, homoerotic themes, flowers, and portraits of celebrities. His formalist approach to photography allowed the artist to approach subjects primarily through beauty and composition, and secondarily through content. It is easy to find the documentary value of his work, however it is the plight for artistic expression of which he was most concerned, consistently searching for new levels of self-expression. His work continues to be considered taboo by many, yet he remains to be one of the most revered American photographers.

Accomplishments

- Mapplethorpe was interested in universal values like symmetry and beauty, and approached all of his subjects with the same discerning eye through sublime composition, use of color contrasts, and cinematic lighting. He is considered a formalist for his sculptural use of photography and often listed Michelangelo as a primary influence.

- For him, photography was a means to an end in a search for original self-expression. His utilitarian use of the medium resulted in a revolution for art photography. During Mapplethorpe's lifetime, photography wasn't a respected means of art making as it is today. He was able to bring photography into major museums during the course of his career, most notably one of his final shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1989, and many museums posthumously.

- Some of his work was considered too edgy, on the verge of being pornographic or racist. Specifically, his work from the early 1980s, which featured graphic depictions of homoerotic or S&M based imagery, and his fascination with black nude male bodies. This work was not made with the intent of having political or ideological framework, rather he simply photographed what he thought was beautiful and otherwise treated all subjects with the same treatment, whether they were penises or flowers.

- Mapplethorpe will be remembered historically as a traditional black and white photographer, but he also worked in sculpture, combines, films, and was hired to photograph celebrities for magazines. It is now considered common for artists to dabble across mediums and find one that best suits their message. For Mapplethorpe, photography was an immediate means to producing a sculptural work. He often said that he would work in marble if it weren't so time consuming.

- Mapplethorpe's tragic end enacts the allegory of artist as cultural hero. He is remembered as one of the first celebrity victims of AIDS, and because of this, his legacy is often used to symbolize the struggle for gay liberation.

Important Art by Robert Mapplethorpe

Untitled (Blue Underwear)

This early work explores Mapplethorpe's interest in the use of sexualized, readymade objects that are the precursor to his career in photography. This sculpture is one of the only surviving artworks from his first exhibition outside of school in 1970 titled Clothing as Art at the Chelsea Hotel. The artist created a sculpture consisting of two simple items: a wood frame conventionally used to stretch canvas, and a personal pair of simple blue briefs. The briefs are pulled inside out exposing the stitch work as well as exposing the most intimate section of the garment toward the viewer.

Fashion and style were closely linked to personal identity for Mapplethorpe, and stretching this sexualized garment to the point of strain on the fibers offers a look into the idea of clothing as access to hidden desires for the artist. Instead of using a frame traditionally used to mount and stage a canvas, Mapplethorpe intentionally exposes the frame as a part of the artwork. This is crucial to the piece, for he is referencing the act of art making by leaving the wood exposed while at the same time elevating a personal item into a public readymade intended for an art audience. Mapplethorpe understood that clothing is used to mark sexual identity and independence, and he used art to provide a context for erotic display.

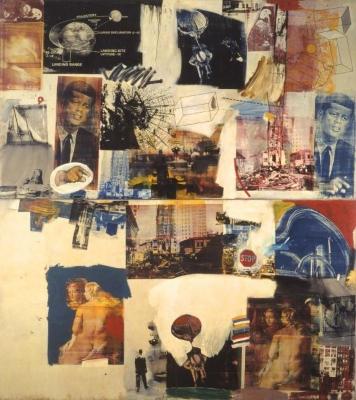

Untitled declared Mapplethorpe's artistic thinking as an emerging artist and pointed to his future artistic style. The assemblage is one of Mapplethorpe's earliest surviving works and he created several similar works of briefs stretched to wood frames. His interest in the heightening of quotidian items into art objects gives reference to his influences of Dada, Pop art, and Andy Warhol; and his knowledge of assemblage artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Yet, his theme of using the frame to create a visually enticing object remains unique to Mapplethorpe's claim to artistic innovation.

Fabric, Wood, Paint - J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angles County, Los Angeles

Leatherman #1

Leatherman #1 is a mixed media piece that features a half-tone print of a man in a leather jacket and underwear holding a bullwhip - the print is actually a clipping from a pornographic magazine. The clipping is overlaid with plastic mesh giving the illusion of Ben-Day dots, which is a process used in screen printing. The background of the image is colored-in red and situated asymmetrically against blue and white velvet flocked damask wallpaper within a handmade shadow box frame. A small metal five-pointed star is glued on the image. The centerpiece was taken directly from and inspired by his interest in homoerotic "physique" magazines, which were an antecedent to more hard-core types of pornography (prior to the mid-1960's publications were prohibited from printing full frontal male nudity in the United States). The style of Leatherman #1 references the Pop art movement with bright colors, the illusion of screen printing, and the found photo as the key subject in this piece. The juxtaposition of the sexualized gay man in leather against the pastel-colored, floral motif emit synchronized feelings of pain and pleasure.

Though largely overlooked, his early works are important to understanding Mapplethorpe's formative years. Leatherman #1 shows Mapplethorpe exploring his artistic and sexual individuality through a play on cultural norms and visual cues. Whereas Pop art often used celebrities as their subjects, Mapplethorpe has chosen to mock the mainstream art establishment, because blatant sexuality, gay rights, and even photography were marginalized at the time. This work was created within the year after the famous Stonewall riots, which were a series of violent demonstrations that fought against gay oppression and police brutality. At the time, the need for an individual voice through art seemed even more urgent in conjunction with a gay male voice.

Mixed Media - J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angles

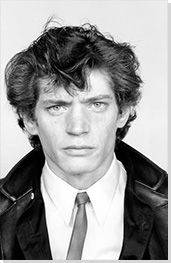

Self Portrait

Self-Portrait is a black and white photograph of a young Mapplethorpe posed shirtless against a white background. Donning a boyishly playful smile with an arm outstretched across the background wall, his body remains mostly out of frame. The arrangement of his arm and relaxed hand hold a subtle resemblance to a crucifixion and might hint at his interest in spirituality. Self-Portrait marks Mapplethorpe's transition from collage, mixed media, and assemblage to focusing exclusively on photography. This photograph is also the beginning of Mapplethorpe's dedication to self-portraiture as a central theme in his work. He would go on to create a wide variety of self-portraiture exploring the interconnections of spirituality, nudity, and eroticism.

This is a rare image of Mapplethorpe for he depicts himself as an innocent, happy young man; his curiosity is distinct from any image seen in his subsequent portfolios. He had many different personas that he captured on film, which range from blatantly pornographic, to serious and stern with little human emotion or expression. This photograph is amateur in comparison to his later work, before he refined his studio techniques. Mapplethorpe's studio photography legacy as it stands today is akin to that of Richard Avedon and Irving Penn with the utmost care and attention paid to bringing the essence of the subject on to film through manipulation of light and shadow. This portrait from 1975 shows the artist coming into his own and becoming self-aware as studio photographer, artist, subject, and sexual object.

In the canonical text Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes writes about this photograph and the relation it holds to erotic photography generally. He states, "The erotic photograph...does not make the sexual organs into a central object; it may very well not show them at all; it takes the spectator outside its frame, and it is there that I animate this photograph and that animates me." Of Self-Portrait specifically, Barthes continues, "This boy...incarnates a kind of blissful eroticism; the photograph leads me to distinguish the 'heavy' desire of pornography from the 'light' (good) desire of eroticism; afterall, perhaps this is a question of 'luck': the photographer has caught the boy's hand (the boy is Mapplethorpe himself, I believe) at just the right degree of openness, the right density of abandonment: a few millimeters more or less and the divined body would no longer have been offered with benevolence (the pornographic body shows itself, it does not give itself, there is no generosity in it): the photographer has found the right moment, the kairos of desire."

Photograph on paper, dry mounted on board - Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, New York

Mark Stevens (Mr. 10 ½)

Mark Stevens (Mr. 10 ½) portrays a well-endowed male figure, the gay porn star Mark Stevens, outfitted in black leather chaps. Stevens requested to remain anonymous, and in all of Mapplethorpe's photographs of this subject, his body is carefully cropped at the torso. His body is exerted over the tall granite podium, his chest and arms flexed tight to balance his upper body. At the center of the photograph lays his penis directly on the podium, a passive and decorative art object. Mapplethorpe showcases his attraction to men through capturing the definition seen in the subject's sculpted muscles down to the veins of his penis. Steven's penis becomes a human sculpture elevated atop the pedestal, drawing attention to the sculptural elements of the human body and likening them to the level of art. Here Mapplethorpe reimagines the sculptural object as a human body part. More specifically, the artist is making a statement by elevating the gay male body to that of classical sculpture and allegory by balancing provocation and aesthetic desire.

Mark Stevens (Mr. 10 ½) purely represents the style and imagery Mapplethorpe became (in)famous for at the height of his career: homoerotic and sexually charged black and white photography. Mapplethorpe defended his controversial photos like Mark Stevens by neutralizing the sexual tension in his photographs by using classic photographic techniques. Mapplethorpe exemplifies this by stating, "Everyone is in one way or another involved in sexuality... if you believe sex is dirty, then everybody has a dirty mind. But I never considered sex to be dirty." Despite this opinion, the photo was one of the photographs raised by Senator Jesse Helms in 1989 to restrict the content of federally funded art.

Gelatin silver print - J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

Jim and Tom, Sausalito

This photograph is a documentation of a consensual sex act between Mapplethorpe's friends Jim and Tom and is part of the X Portfolio. Jim is shirtless wearing a fetish hood, leather pants, and boots, he stands holding his penis in a gloved hand urinating directly into the mouth of Tom, who is kneeling on the ground with his mouth agape and his hands on his thighs. This image was taken in an abandoned military bunker in San Francisco in front of a rough graffiti wall, with light coming from above which creates a dramatic shadow in the center of the image. The bodies are connected through the stream of urine highlighted by the slice of light. This is a staged act; light and shadow are controlled as well as the subject of the image very clearly orchestrated.

This shows a high level of trust between the partners, as well trust in the photographer. The level of intimacy evoked makes this different from other photographers shooting oddities or fringes of society like Diane Arbus, where the images are exploitative and feel like a betrayal of trust between artist and subject. Mapplethorpe was very clear that he was not a voyeur, as he often said, he "recorded it from the inside." Although this is an insider perspective, he always removed his subjects from their original environment. He photographs life outside of where life happens by decontextualizing the object or person in the photographic studio - thus lending the viewer a disembodied look at the subject. "Life is more interesting without a camera. I take pictures and it adds to my life. If I had a choice of photographing the party or going to the party, I'd certainly go to the party."

This image is one of seven photographs used in the 1990 censorship trail in Cincinnati, and was a popular target for critics of contemporary art. He said of this series, "I wanted people to see that even those extremes could be made into art. Take those pornographic images and make them somehow transcend the image."

Selenium toned gelatin silver print, Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles - County Museum of Art; partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Patti Smith

In a typical household setting, young Patti Smith ceremoniously cuts her hair. She stands facing the camera staring directly into the lens; uninhibited by the camera's gaze. The cat perched next to Smith channels her grimaced, unbroken stare. Just as much as the camera follows Smith, she gazes back. Mapplethorpe captures Smith's essence, unrestrained, confident, and indifferent even during a seemingly impromptu occasion. True to his style, he represents Smith directly, but with a unique and different approach to intimacy than seen in his homoerotic photos. The scene isn't a bedroom or glossy black background, but a simple home setting with a housecat. She was Mapplethorpe's long-time friend and lover, and they spent many years living together during the early part of their careers. Smith acknowledges her defiance to convention by this act -she without precision cuts her hair into a less feminine coif. Smith says she didn't "want to walk around New York looking like a folk-singer. I like rock 'n' roll. So I got hundreds of pictures of Keith Richards, and I hung them up and then just took scissors and chopped away until I had a real Rolling Stones haircut." This photograph is a visual ballad to the connection they shared in a close space for many years during their formative period.

Gelatin Silver Print - Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angles

Lisa Lyon

Lisa Lyon is a testament of Mapplethorpe's commitment to formalism, in both male and female form, punctuated at the latter part of his career. The composition demonstrates his mastery of lighting, careful staging, and ornamentation to create a mysterious portrait of Lyon. Mapplethorpe often cropped his subjects at the torso, or obscured the identity to bring attention to the physical attributes of the subject, all while protecting their privacy. In this portrait, Lyon has a dramatic white curtain draped over her head to conceal her feminine beauty and in contrast she stands confident with her arms up flexing her biceps. In this opposition, she is allowing the viewer to objectify her without having the option to gaze back. The contrapposto masculine pose evokes the historical interconnection between classical Greek sensuality and stylization of nature.

Lisa Lyon met Mapplethorpe in 1980 and they collaborated on many photography projects including a film as well as a book titled, Lady, Lisa Lyon (1983). For Mapplethorpe, Lyon blurred the line between male and female with her strong female form, "When I first saw her undraped it was hard to believe that this fine girl should have this form." Lyon was the first World Women's Bodybuilding champion, and although her physique is tame for contemporary standards due to growth hormones and testosterone used in the sport, at the time her androgynous body defied popular conceptions of femininity. Not only did Lyon appeal to Mapplethorpe's love of sculptural bodies, she challenged cultural visual standards, which allowed the artist to explore gender lines that encouraged the enigmatic interplay between gender and disguise. Mapplethorpe loved the interplay of classic feminine beauty and masculine strength and she became one of his most important muses.

Medium gelatin silver print

Ken Moody and Robert Sherman

This portrait portrays two of Mapplethorpe's friends - a black man, Ken Moody, and a white man, Robert Sherman. Sherman reaches his head over Moody's shoulder, as both men face directly to the left side of the frame. Directional lighting captures subtle undulating forms found on the individuals' skin.

Mapplethorpe never worked in documentary style and instead always insisted on the importance of the camera and studio to sculpt light and form. The models tried several positions and eventually settled on Sherman's longer neck reaching over Moody, that is to say that the posing of the two is not attempting to make a social statement of a plight about race, although many have read into the image as such. Both Sherman and Moody had lost all of their hair at a young age, and Mapplethorpe brought them together through their similar attributes, and for their striking contrasting skin tones which are on opposite sides of the spectrum. This is the key element of this photograph. Moody's black skin would fade into the background had it not been for the subtle gradation of greys on the backdrop through Mapplethorpe's mastery of lighting. Furthermore, the use of black and white photography as medium is exaggerated in this photograph, which allows the artist to explore these binary relationships. The figures represent human forms in an unequivocally sculptural manner, and the artist had once stated, "If I had been born one or two hundred years ago, I might have been a sculptor, but photography is a very quick way to see, to make sculpture."

Gelatin silver print - The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Calla Lilly

The subtle gradation of light in this photograph exhibits the well-defined lines and the natural shape of the lily. The flower dominates the picture plane and the highly-detailed platinum print creates a stark contrast by portraying the extreme white against the extreme black with subtle gradations of grey tone found on the pedal and the pistil. Mapplethorpe often explored this use of gradation, even in his portraits. The flower "portraits" make it completely clear that Mapplethorpe was an accomplished studio photographer, no matter what the subject.

Calla Lily, depicts two of Mapplethorpe's most famous motifs: timeless black and white photography and floral still lifes. His floral still lifes were some of the few photographic projects he shared with this family. He sought to become a formal master whether approaching homosexual themes, nudity, portraiture, sadomasochism, or floral still lifes. "Taking pictures of sex is no different than photographing a flower, really... It's just submitting to whatever is going on and trying to get the best possible view of it." His second portfolio, entitled Y, displays his floral still lifes and was published between his X Portfolio of homosexual S&M and the Z Portfolio of black men. Although he treated all his subjects the same way artistically, to put the flower photographs into context of his entire oeuvre, it is hard to ignore the phallic shape and the overall sexual nature of flowers. Still lifes were also a major part of his twenty-five year retrospective exhibition, The Perfect Moment.

Platinum Print - The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Andy Warhol

Here Warhol's bust is centered in a soft white circle around his head (acting as a halo) placed within an opaque black square frame. Warhol wears his trademark black turtleneck and blank stare. The cruciform shape frame recalls Mapplethorpe's reoccurring Catholic motifs and the Catholic background both he and Warhol shared. The frame and haloed light is to suggest the god-like status Warhol has found through fame.

Mapplethorpe admired Warhol as a teenager and after he moved to New York Mapplethorpe soon competed with Warhol to take celebrity portraits. Both Mapplethorpe and Warhol came from middle-class, suburban backgrounds, attended school for graphic design and advertising, and both wanted to become famous - not just successful. Andy Warhol is one of numerous portraits they took of one another. However, their portraits were wrought with underlying artistic competition and distrust. Until Mapplethorpe began dating Wagstaff, Warhol thought of Mapplethorpe as suspect. Both artists were afraid the other might steal their ideas and the limelight. Here, Mapplethorpe photographed Warhol in a more or less positive perspective, while on another occasion, Warhol photographed Mapplethorpe in deep red, owing perhaps to his relentless distrust of Mapplethorpe.

Gelatin Silver Print - The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, New York

Biography of Robert Mapplethorpe

Childhood and Education

Born in 1946, Robert Mapplethorpe was the third of six children. His father, Harry, worked as an electrical engineer while his mother, Joan, stayed at home raising their six children. Mapplethorpe grew up in a conservative Catholic household nestled in the quiet Queen's suburb of Floral Park. Mapplethorpe described his hometown as too safe to stay, "I come from suburban America. It was a very safe environment, and it was a good place to come from in that it was a good place to leave." The Mapplethorpe family attended Mass every Sunday and Robert served as an altar boy and occasionally made art for their family priest. His father, an amateur photographer himself, had a dark room in his basement. However, Mapplethorpe did not show an early interest in photography.

Mapplethorpe finished high school in just two years. He enrolled at the Pratt Institute near Brooklyn, New York at the young age of 16. Despite his father's disapproval to study art, he started school majoring in advertising design. Like many young students, college was a time for personal exploration and a newly found independence from his religious upbringing. He continued his involvement in masculine activities such as the ROTC and The National Society of Pershing Rifles, but began to question his sexual identity through gay pornography magazines - of which he would save cut-outs, many of these cut-outs showed up in his early artwork. He also began experimenting with psychedelic drugs. Mapplethorpe and his friends would often create collages and other assigned art projects while on LSD. He enjoyed the spontaneity of collages and assemblages and despised his photography courses. On a few occasions, instead of creating original work, he would take photographs from his father's darkroom to complete his photography assignments.

In 1966, Mapplethorpe switched his major from advertising design to graphic design. The new discipline gave Mapplethorpe a better chance at expressing his outgoing and unique personality. Graphic design opened his eyes to other mediums and he began making necklaces, drawings, jewellery, and assemblages. Mapplethorpe left Pratt in 1969, just one course shy of receiving his B.F.A.

Around that time, he met his only female lover and lifelong friend, Patti Smith. They lived together in Brooklyn, and later at the Chelsea Hotel where they would attempt to trade artworks for rent. They often experimented with drugs and helped one another develop their artistic styles. Their relationship was intense and often tumultuous, but they remained close friends. Mapplethorpe often photographed Smith, and stated that, "Patti was an unbelievable subject, there were so many sides to her, so many aspects that changed my world vision." Smith matched Mapplethorpe's ambition and drive to become a famous artist in New York during the early 1970s, and went on to become one of the most revered female musicians.

One of the main artistic figures that influenced and informed Mapplethorpe's early artistic style and personal goals was Andy Warhol. He became fascinated with Warhol and the growing counterculture lifestyle prevalent in New York during in the early 1970s. Warhol, like Mapplethorpe, was an artistic outsider who grew up with middle-class roots. Warhol succeeded in the art world creating a name for himself and lived a lavish lifestyle of New York. Mapplethorpe and Smith often frequented the same nightclubs as Warhol's group including Max's Kansas City, which was rich in New York's nocturnal cultural.

Early Period

Having been heavily influenced by Warhol and his experimental underground film, Chelsea Girls (1966), set in the Chelsea hotel, Mapplethorpe moved into that same hotel with Smith in 1969. He was hired on as a photographer for Interview magazine (co-founded by Warhol) which covered international celebrities, artists, and musicians alike. Like many aspiring young artists living on the fringes of society, Mapplethorpe started living a bohemian lifestyle and at times was literally a starving young artist. He and Smith used cheap materials to create their artwork, like magazine cut outs, cardboard, paper, and other found objects on the street. It wasn't until their neighbour, Sandy Daley lent Mapplethorpe her Polaroid that he began taking pictures of himself and Smith. He enjoyed the intimacy and quick reproduction that Polaroid offered, which matched Mapplethorpe's impatience and his impulsiveness, "If I were to make something that took two weeks to do, I'd lose my enthusiasm. It would become an act of labour and the love would be gone." Daley remembers Mapplethorpe intentionally not buying food just to buy more film as he began to experiment with the Polaroid. Surviving Polaroids show him lifting emulsions from one piece of paper, applying new ink, and re-applying it to another surface.

At a dinner party in 1971, Mapplethorpe met the highly influential James McKendry, curator of photography and prints at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Meeting McKendry changed the course of his artistic career in a matter of months. McKendry invited Mapplethorpe to view his collection of historic photos at the museum. Photography had not seriously been considered a fine art, but the collection of photos inspired Mapplethorpe to take up photography as an artistic medium. McKendry later gave Mapplethorpe a Polaroid camera for Christmas to foster his budding photography interest. Through their friendship, McKendry had fallen deeply in love with Mapplethorpe. His love went unrequited and produced depressive mood swings in McKendry. Health complications related to his excessive lifelong drinking habits placed McKendry in a hospital where Mapplethorpe took the last portrait of his friend in 1975.

Mapplethorpe continued to experiment with a range of mediums including Polaroids, collages, and jewellery, and in 1972 he presented his work to curator Sam Wagstaff. As the senior curator at Wadsworth Athenaeum and former curator of contemporary Art at Detroit Institute of Art. Wagstaff became another highly influential connection in Mapplethorpe's career and personal life. He became Mapplethorpe's lover, patron, and financial support for the better part of his career - buying a loft for him in New York, a medium-format Hasselbad camera, and introducing him to the glamorous social life of New York City's upper echelon. Mapplethorpe also helped Wagstaff to become more confident with his sexual identity as a gay man. Sexually charged and intimate photographs of Mapplethorpe and Wagstaff show the trust Wagstaff placed in Mapplethorpe. Furthermore, Wagstaff legitimatized Mapplethorpe's provocative photography to the public in many of his written works and interviews. Mapplethorpe's extreme ambition and social connections helped him land his first solo gallery exhibition of Polariods in 1973 at New York's Light Gallery. Shortly after, he began sending his film to commercial printers, producing silver gelatin prints, and was soon exhibiting his Polaroids alongside Warhol in New York.

Mature Period

The mid-1970s mark the apex of Mapplethorpe's career through his prolific portraiture of close friends, socialites, and his photographic investigations into the darker side of sexual fantasy. In 1975, Mapplethorpe photographed Smith for her debut studio album, Horses. Set in Wagstaff's penthouse, Mapplethorpe demonstrated his maturing black and white style. The photo showed an androgynous figure wearing crisp black jeans, a tucked in white shirt, and an untied tie draped around her neck. A jacket is casually slung across her shoulder drawing a comparison to past music greats like Frank Sinatra. The critically acclaimed album and album cover elevated both Smith and Mapplethorpe to a level of stardom that they had aimed to achieve for many years. Mapplethorpe also started to receive more projects and further recognition from Interview magazine. After finding out that Mapplethorpe was seeing Wagstaff, Warhol warmed-up to the idea of Mapplethorpe becoming a more integral part of the magazine. He became embedded in the "right circle", and was often commissioned to photograph the wealthy in Britain, France, and Spain. Mapplethorpe experienced a disconnect between his paid commercial work and his personal photography:"I think the interesting thing about Penn and Avedon is that they started in commercial photography and then they got into 'art' and they separated the two. Their art was opposed to their work." For Mapplethorpe, his interest was to photograph the people around him and have his art serve an autobiographical purpose - his work was always connected to his art.

The private gay nightclubs like the Mine Shaft, were places for men to go to engage in bondage and leather play which involved (but not limited to) S&M (sadism and masochism), role-play, fetish, and scatological sex. These were safe places for men to indulge in fantasy and find freedom and comfort in their sexual preferences. This is a stark contrast to the world outside where homosexuality was still seen as forbidden, for gay rights were still in a transformative era. At these nightclubs, he would meet men that would later be his photographic muses. Many of the men that were included in his X Portfolio published in 1978 were friends and lovers met at these private clubs. The portfolio consisted of thirteen infamous photographs that include a self-portrait of the artist with a bullwhip inserted into his rectum, two lovers engaging in anal fisting, a man inserting his pinkie finger into his urethra, a man posing submissively on all fours in a head-to-toe latex outfit, among others. This portfolio hardly loses the shock value even among contemporary audiences, and would later define an era of artistic and sexual freedom. Mapplethorpe originally signed his name with a simple x, in his early career, creating a double entendre. "I don't photograph things I've not been involved with myself... I went into photography because it seemed like a perfect vehicle for commenting on the madness of today's existence. I'm trying to record the moment I'm living in and where I'm living which happens to be New York. I'm trying to pick upon that madness and give it some order. As a statement of the time it's not bad in terms of being accurate. These pictures could not have been done at any other time." Yet, not everyone agreed with Mapplethorpe's approach. Despite the Holly Solomon Gallery representing Mapplethorpe (in part to his connection to Wagstaff), Solomon refused to show the S&M work in an upcoming show. Wagstaff and Mapplethorpe responded by organizing a second show in New York on the same night. Solomon's show consisted of portraiture for the uptown crowd and the other show displayed the S&M images.

The X Portfolio commenced the tripartite division of his mature work: X, Homosexual Sadomasochistic imagery (1978), Y, floral still lifes (1978), and Z, nude portraits of black men (1981). The controversial X Portfolio consisted of raw, uninhibited portraits sparking strong reactions from viewers and eventually building his artistic reputation as a fine art pornography photographer. While the Y and Z albums countered his provocative portraits with finely captured "portraits" of flowers and sculptural male forms. He understood the connection between his classic photos of flowers and portraits and that of sex acts, "I'm working in an art tradition ... to me sex is one of the highest artistic acts."

Mapplethorpe earned his first solo museum exhibition at The Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia in 1978. In the following years, his artwork showed at other museums and galleries in the U.S. and around the world. Shortly after X and Y were published, he began working on his Z portfolio creating figural studies of the black made body.

Just one year later, Mapplethorpe took on another new interest: a female body-builder named Lisa Lyon. Mapplethorpe was enticed by her muscular, yet feminine image. "It's the first time I've seen a form like that. It's completely new territory. When I first saw her undraped, it was hard to believe that this little girl could have this form." Lyon also reminded him of his classical influences, such as the sculpture Michelangelo created during the Renaissance, "Lisa Lyon reminded me of Michelangelo's subjects, because he did muscular women." The two collaborated on many projects, including Lady: Lisa Lyon (1983). The portfolio of Lyon helped Mapplethorpe prove he was not just a photographer of solely men, or a pornography photographer, but also a formal master of body-as-sculpture.

His experimentations in finding new forms also led Mapplethorpe to explore new photographic techniques. In 1983, he experimented with silver-dye bleach prints called Cibachrome, platinum prints, platinum prints on canvas, oversized platinum prints along with other nuanced techniques. The high-quality and detailed platinum print helped blur the barrier of painting, sculpture, and photography that Mapplethorpe set out to destruct at the beginning of his career. Mapplethorpe hired staff assistants for his darkrooms, like Tom Baril, who became a master printer while working for Mapplethorpe. Mapplethorpe was more interested in shooting the photograph than the process of printing. He was nevertheless obsessed with realizing his own vision and was a self-confessed perfectionist. He ended up spending much time with his assistants by directing edits, and doing the necessary touch-ups.

Later Period

Around 1980, Mapplethorpe moved away from S&M images and applied himself primarily to the formalist approach of traditional subjects like flowers and nudes. He admired Ed Ruscha's ability to remove a subject from any context and sought to produce images in this severe formal artistic language. Watermelon with a Knife (1985), Thomas (1986), and Leaf (1989) all emotionally disengage with his previous provocative style.

In 1986, Mapplethorpe went to the hospital for pneumonia where he was diagnosed with AIDS. Just one year later, Wagstaff died of complications related to AIDS (and Warhol died of general health issues the same year). With Wagstaff gone, and his recent diagnosis, Mapplethorpe worked feverishly to complete all the work necessary to become a household name - despite his acknowledgement of not being able to enjoy his success. Once news broke about his diagnosis, the demands for his photographs were greater than ever. As one of his assistants, Tom Baril said, "He didn't stop shooting until he physically couldn't get out of bed."

Mapplethorpe was admitted to the hospital again in July of 1988. Just one week later The Whitney Museum of American Art opened a mid-career retrospective of his work, which was a great success and a rare honor for a photographer at that time. Understanding that he was a dying man and his final days were upon him, he planned a final exhibition titled, Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment. The show was curated by Janet Kardon of Philadelphia's Institute of Contemporary Art and opened on December 8, 1988. This exhibition featured the X, Y, Z Portfolios, which had never been shown before in their entirety. Eight months after the exhibition opened, Mapplethorpe died of AIDS at a hospital in Boston.

Nevertheless, Mapplethorpe's artwork continued to make waves of controversy after he had passed. The Perfect Moment exhibition, funded in part by the National Endowment of the Arts, was slated for a posthumous nationwide tour. The first host museum for the exhibition was the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. The Corcoran cancelled the exhibition due to protests of the few images that portrayed homoerotic and sadomasochistic content, and its director resigned in the controversy. The exhibition was the put at the forefront of the late 1980s culture wars headed by Senator Jesse Helms who questioned government funding for the arts and wanted to impose restrictions on what was supported. He successfully shut down the exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery. Along with Senator Helms, was the right wing politician Pat Buchanan and religious leaders such as Donald Wildmon and Pat Robertson who together focused a concerted attack on the National Endowment for the Arts claiming that the government was supporting artists and museums that were involved in what they considered "anti-Christian bigotry". Though curators and art critics defended Mapplethorpe's homoerotic photography as demonstrating how far photography has come as a fine art, Senator Helms believed his work further derogated fine art to corporeal base. The exhibition was moved to a nearby non-profit called The Washington Project for the Arts, which held a record of 48,863 visitors.

The matter of free expression became a complex congressional topic - one Mapplethorpe no doubt would have enjoyed being at the heart of. When the show travelled to the Cincinnati Contemporary Art Museum, the museum director Dennis Barrie was charged with obscenity for the first time in U.S. history. The jury later found Barrie not guilty. Despite conservative lawmakers promoting censorship of the arts, Mapplethorpe's work has since been exhibited in museums and galleries around the world.

The Legacy of Robert Mapplethorpe

Louise Bourgeois said of his work, "He is famous not for his flower pictures, he is famous for his objectionable sexual representation." Mapplethorpe was not just a documentarian of the homoerotic lifestyle of the 1970s. There is no doubt that he influenced the art world as a whole, LGBT activism, and censorship laws. Many attribute his giant influence on photography, making it a respected artistic medium, for previously photography was considered utilitarian. His unique contribution to photography has significantly expanded the history of the medium. Not only was he elevating photography to high art standards, but he was a provocateur, so much so that it was considered criminal. Mapplethorpe's name is connected with the infamous culture wars initiated by Republican Senator Jesse Helms. Helms deemed Mapplethorpe's artwork obscene, and this sparked national debate on whether or not tax dollars should fund the arts, as his work included homoerotic images and was shown at Washington's Corcoran Gallery that was funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts. Other artists were targeted such as Karen Finley and Andres Serrano, and the resulting court case was short lived. Such conversations of art censorship continue in American society today, although Mapplethorpe helped artists retain their freedom of speech by pushing the envelope and raising the bar through art.

Not only has his work irrevocably impacted the world of art, but also Mapplethorpe's message of gay rights and AIDS awareness continue to hold sway. A year before his death, he founded the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation which handles his official estate and donates millions of dollars in medical research as well as funding the fight against AIDS. In 2011, the Foundation donated an archive that spans from 1970 to 1989 to the Getty Research Institute where his artwork will be preserved and protected for future generations.

Influences and Connections

-

![Andy Warhol]() Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol ![Patti Smith]() Patti Smith

Patti Smith![Philip Glass]() Philip Glass

Philip Glass

-

![Catherine Opie]() Catherine Opie

Catherine Opie -

![Richard Avedon]() Richard Avedon

Richard Avedon -

![Peter Hujar]() Peter Hujar

Peter Hujar ![Jonathan Becker]() Jonathan Becker

Jonathan Becker![Debbie Harry]() Debbie Harry

Debbie Harry

![Mary Boone]() Mary Boone

Mary Boone![Fran Lebowitz]() Fran Lebowitz

Fran Lebowitz![Bob Colacello]() Bob Colacello

Bob Colacello

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI