Summary of Agnes Martin

Agnes Martin's sparse, luminous canvases are not easily categorized as they are at the crossroads of several disparate 20th-century styles. An intensely private person, Martin was diagnosed with schizophrenia in her 40s; she led an austere and solitary existence in a remote area of New Mexico for most of her working life. Like many artists in the 1950s and 1960s, she was influenced by Zen Buddhism and Taoism that contributed to her interest in nature. Despite the abstraction of her paintings, it was the innocence and simplicity of everyday life - especially the natural world - that she attempted to capture in her work.

Accomplishments

- Martin used the grid as an organizational element in canvases that were awash with color, thus seamlessly blending what on the surface are two very different art styles: Minimalism and Color Field.

- Martin's works are non-representational, yet the titles of her paintings and her own words about her art and life indicate that she was strongly influenced by nature - a focus that brought together different areas of her life. Her adherence to Buddhism encouraged her to rely on her everyday surroundings for subject matter; and her schizophrenia meant that she did not relate well or easily to humans, so that nature represented a calm, ordered refuge.

- Martin's use of the grid along with her focus on non-representation released the artist from the burden of traditional subject matter while allowing her to explore infinite variations of subtle color. The resulting freedom of her artwork was at odds with the monastic restraint of her daily life.

Important Art by Agnes Martin

Untitled

Martin destroyed much of her work made before the late 1950s when she shifted to a grid format, so works from this period of her oeuvre are scarce. Her early style has been compared to that of Arshile Gorky and, like his works, Untitled displays Martin's debt to Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism. This canvas, with large swaths of earthy clay, black, and sunset orange, incorporates the biomorphic elements and expressive lines of those movements, while also absorbing the landscapes of the Southwest, where Martin would periodically return. The triangles echo the mountains and hills of Taos, and the colors recall the rusty, arid backdrop that she encountered daily. Although the local flora and fauna appealed to Martin greatly, she was also involved with the artists that flourished in Taos and engaged actively with the community during her time there in the 1940s and 1950s.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Scott K. Stuart, Albuquerque [copyright 2012 Agnes Martin/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York]

Window

With Window, Martin's forms became less organic and more rigid as she experimented with rectangular forms, anticipating the later introduction of the grid's mathematical precision in her work. The title of the piece references a recurrent subject in Western painting, yet in this work the "windows" are opaque and do not allow a view. This lack of view accords with Martin's statement that she paints "with my back to the world," implying that her works do not attempt to capture reality or personal experience, but instead evoke a response in the viewer: a mood, an emotion, a fleeting moment of joy. Although this work was created during the first years of Martin's final return to New York, Window still incorporates a Southwestern palette, while abandoning the curved line of earlier work. Here, she reduced her format to the square and her colors to cooler grays, beiges, and blues, but the title and the colors still suggest a landscape, though one that has been compressed into four geometrical shapes.

Oil on canvas - Dia Art Foundation, New York

Night Sea

A few years prior to painting Night Sea, Martin began utilizing grids in her compositions that freed her from representation; she settled on a six-foot square canvas for all of her works, further simplifying her practice. The art historian Barbara Haskell notes that Martin's shift may have been influenced by Lenore Tawney, a Coenties Slip neighbor and fiber artist who worked with looms and with whom Martin had a relationship. The grid's abstraction released Martin from any obligations to subject matter, while allowing her to explore endless variations of color, thus providing her a freedom that she did not allow herself in her (self) circumscribed existence. Although the painting does not obviously depict a "night sea," the two brilliant hues of blue are under-painted with a gold leaf grid that shimmers and seems to move like light reflecting on an expanse of water, of which she had a view from her studio on the East River. What initially appears to be a solid mass of pure blue from afar becomes a richly complex surface upon closer inspection.

Oil and gold leaf on canvas - Private Collection

Leaf

Around 1964, Martin began using acrylic paint rather than oil and simultaneously replaced colored pencils with graphite. The thick, heavy surfaces of oil gave way to acrylic washes that seemed to melt into the canvas, heightening the visual clarity of the work. In Leaf, the grid continues to be the architecture of Martin's composition, and the texture of the work is simplified down to intersecting graphite lines, a change from the thick paint used in previous canvases. As her work gradually turned away from a pronounced materiality through these new techniques, it began to change in other ways as well, becoming more lyrical and contemplative. The titles she assigned to her work also reflected her ongoing interest in nature and the environment. Martin in fact claimed that the idea of a grid first entered her mind when she was thinking about the innocence of trees. The grid, rather than conveying mathematical precision, allowed Martin to represent the order and simplicity of nature without reproducing it in a representational manner. Her working method with her grid paintings was unswerving. She would wait on a full-color vision; once it arrived she worked out the composition through fractions and long division on paper; then using tape and a short ruler, she would mark out the grid on a gessoed canvas. The color was applied quickly and if there were any errant drips or other mistakes, she would destroy the canvas, sometimes starting over half a dozen times before she was satisfied.

Acrylic and graphite on canvas - Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas

Gabriel

After leaving New York permanently and traveling through America and Canada, Martin returned to New Mexico to live in isolation. She focused intensely on her writing and made her first foray into filmmaking with Gabriel, her only feature-length film. The film follows a young boy who observes the surrounding environment with great curiosity and intensity. Martin eschewed narrative, instead allowing the camera to meander with the boy, who is exposed to trees, rocks, sand, water, and sun. The lack of storyline and continuity break from Martin's rigid grids, demonstrating an alternative method of realizing her lifelong search for peace through artistic production. The gallerist Arne Glimcher recalls Martin pursuing another film, going so far as hiring actors and shooting several scenes. The project was never completed and was eventually abandoned. Although Martin did not activate her filmmaking career, Gabriel was another effort in exploring landscape, prompting an understanding of humans through their reaction to nature.

16mm film with color/sound, 79 minutes - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

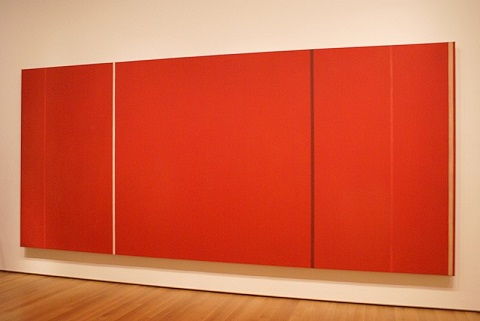

Untitled XXI

Untitled XXI is an example of Martin's work after the mid-1970s. Whereas work such as Night Sea dissolved grid and color to present a shimmering expanse of blue, Untitled XXI emphasized areas of divided colors that appeared discrete and radiant. As with Leaf, Martin continues to use acrylic washes and graphite pencils, employing the chalky gesso primer as the base for the background. Her palette here remains muted, not straying too far from pastels, pale grays, and blues. Martin, however, utilizes stacks of dusty yellow and pink bands, relying on a slightly warmer, rosier mix of color that harkens back to earlier works that rely on a Southwestern palette, perhaps in this case referencing a sunset. Though Untitled XXI is not explicitly designated as a landscape, by name or representation, Martin throughout her artistic life attempted to capture the sublime of everyday nature through her continued variation on the square format. She began to title her paintings again in the 1990s.

Gesso, acrylic, and graphite on canvas

Biography of Agnes Martin

Childhood

Agnes Bernice Martin was born on an isolated farm to Scottish Presbyterian settlers. Her father, a wheat farmer, passed away when Martin was two and her mother sold real estate to support the family. Martin had a difficult relationship with her emotionally distant mother, but was close to her maternal grandfather, who introduced her and her two siblings to spiritual texts such as The Pilgrim's Progress (1678) by the English preacher John Bunyan. Her family relocated several times, finally settling in Vancouver, where Martin swam competitively and tried out for the Olympic team. She immigrated to Washington in 1931when she was 19, gaining U.S. citizenship in 1950. She pursued studies at the Western Washington State College in Bellingham from 1935 to 1938. She moved around quite a bit on the west coast, teaching at public schools in Washington and Delaware before enrolling in the art education program at Columbia University's Teachers College in New York City, graduating with a BS in 1942. She then pursued graduate studies at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where she also taught, before returning to Columbia to earn her MA in 1952. While at Columbia, she began attending lectures by the Zen Buddhist academic D.T. Suzuki. Martin's aversion to chaos led her to follow the tenets of Zen Buddhism and Taoism throughout her life.

Early Period

In the 1940s and 1950s, Martin divided her time between New York City and the southwest, where she spent a considerable amount of time painting. Having grown up in the Pacific Northwest, the dusty, dry landscape of the American Southwest would continually hold Martin's interest. In 1947, she participated in a study program through the Harwood Museum in Taos, New Mexico, an important hub for postwar landscape painters such as Marsden Hartley and Ernest Blumenschein. In 1957, the influential gallerist Betty Parsons, after seeing Martin's work in New Mexico, convinced Martin to relocate and show at Parson's space in New York. Parsons had helped launch the careers of several American Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko, as well as Martin's friend and confidant Ad Reinhardt.

During the early 1950s, Martin lived in the Coenties Slip enclave of lower Manhattan near Wall Street, where her neighbors included Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Youngerman, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. These artists would often explore downtown neighborhoods, visit each other's studios, and take ferry rides together. She also befriended Barnett "Barney" Newman, who installed her shows. Martin was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia during this period and was subject to auditory hallucinations and catatonic trances throughout her life. She was hospitalized several times beginning in the 1960s, once in Bellevue, where she received shock therapy before her friends could get her out. In this pre-Stonewall era, Martin was also a deeply closeted lesbian, but when asked about feminism at one point, she claimed that she was not a woman.

Mature Period

After Martin exhibited with Parsons, she became associated with Abstract Expressionism and Color Field. She continued to experiment in her practice, arriving at the grid format for which she is famous in 1961. Her work was included at the Solomon R. Guggenheim's landmark "Systemic Paintings" exhibition in 1966, and was also shown at Virginia Dwan's gallery in 1967 at the groundbreaking exhibition "10" that included the work of Carl Andre, Jo Baer, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, and Sol LeWitt. The exhibition is recognized as having established an unofficial canon of Minimalist artists. After the death of Reinhardt and the planned demolition of the building in which her studio on Coenties Slip was located, Martin stopped painting in 1967 - giving away all of her paint supplies and canvases - to travel through the West and her native Canada in a pickup truck and camper. She eventually settled and built her own adobe home in a remote area of New Mexico with few modern amenities and focused on writing poetry. In 1973, she produced a portfolio of serigraphs based on her own drawings, On a Clear Day. That same year, a large retrospective displaying her works from 1957 through 1967 opened at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia. She began painting again in 1974 after a seven-year hiatus. In 1976, she directed the movie Gabriel, her first and only attempt at filmmaking.

Late Period and Death

Martin lived a spartan life in the remote town of Cuba, New Mexico for several years with no television or radio and limited human contact, then moved to Galisteo in 1977. One person who visited her regularly was Arne Glimcher, the founder of Pace Gallery whom she met in 1963 and who became her lifelong friend. In 1992, she settled in a retirement community in Taos at the foot of Taos Mountain, becoming more social and less austere as she aged. In addition to painting everyday from 8:30 to 11:30 in her studio, she collected a number of cars that she kept in pristine condition. In 1995, Martin downscaled her canvases to sixty-inches-square from the six-foot-square stretchers she had used since the 1960s. Prior to her death in 2004, Martin, who had never hired assistants, realized that she would need help physically handling her usual five-foot-square stretchers or be forced to scale down her canvases. Instead of compromising her studio practice, Martin made the resolute decision to quit painting. When she passed away later that same year she had not read a newspaper in five decades. She requested an unmarked grave so that there would be no pilgrimages to her gravesite

The Legacy of Agnes Martin

Although Martin abandoned the artistic hub of New York in favor of a solitary existence on the other side of the continent, she continued to refine her practice while traveling, writing, and experimenting with filmmaking. Perhaps ironically, her seclusion skyrocketed her fame; many devotees ventured to New Mexico in search of Martin, who reluctantly received her callers. The last few decades of her life were spent painting and writing, her practice becoming a metaphor for her search for tranquility. Her work is especially influential in India and China.

Influences and Connections

-

![Rosalind Krauss]() Rosalind Krauss

Rosalind Krauss -

![Louise Nevelson]() Louise Nevelson

Louise Nevelson ![Douglas Crimp]() Douglas Crimp

Douglas Crimp

Useful Resources on Agnes Martin

- Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, RemembrancesBy Arne Glimcher

- Agnes Martin (Dia Foundation)By Lynne Cooke, Karen Kelly, Rhea Anastas

- Agnes MartinBy Barbara Haskell

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI