Summary of Paula Modersohn-Becker

Talented, rebellious, and utterly honest, Paula Modersohn-Becker's groundbreaking life and work expose the scandalous restrictions imposed on women at the turn of the twentieth century, in turn sowing a primary seed for radical change. Inspired stylistically by the Post-Impressionists, Modersohn-Becker's starting point was simple, seeking to investigate, learn from, and to elevate everyday life, with a particular focus on female experience. Painting un-idealized and therefore revolutionary pictures of girls, older ladies, and new mothers she stands as a pioneer exploring transitions of age and maternal identity. Luckily leaving behind a vast correspondence with artist friends and many diary entries, we are given a valuable insight into a woman's desire to be respected in her multiplicity. Sadly killed by the role of being a mother that she was intent on re-envisioning, Modersohn-Becker's last word was schade ("what a pity"), as she died entirely too early, shortly after giving birth.

Accomplishments

- Modersohn-Becker had a life-long love for life drawing and the nude anatomy. By repeatedly painting her own nude self-portrait, she broke down long-standing gender barriers. In order to draw from life she was drawn back and forth to the city of Paris whilst her husband remained living in Germany. She therefore championed independence and proposed an unabashed, alternative way of living for married women.

- Although the subject had previously been discussed in memoirs and literature, Paula Modersohn-Becker was the first person to make the state of pregnancy visible. Today, it is a common occurrence to see the pregnant body in art and in the media, but at the beginning of the twentieth century this was utterly unheard of. She not only highlighted pregnancy as a complex psychological state, but also exposed breast-feeding as another profound and important topic, previously wholly overlooked.

- The idea that Modersohn-Becker's life and art were entirely intertwined is highlighted by her attraction and time spent living with the community at Worpswede. There are various examples of living more communally and artistically that punctuate history (The Bloomsbury Group being the English equivalent). Involvement with such groups provides networks of support and contacts, which in the case of Modersohn-Becker resulted in successful promotion of her work and more exhibitions during the early stages of her career.

- Suppression that Modersohn-Becker experienced at home was sadly in line with a darker suppression of the highest order. Whilst her husband commented of his wife's later portraits, "Her vision is so lacking in femininity and so vulgar...", this was the same stance that Adolf Hitler took in 1937 when he included Modersohn-Becker's work in his Degenerate Art exhibition. The parallel highlights the sad fact that in their refusal to remain indifferent or to practice blind acceptance, "truth tellers" often pose great threat to the appearance of domestic and political order.

The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker

This photograph captures a rare moment of unified embrace between Paula Modersohn-Becker and her artist husband, Otto, in a relationship more often remembered for its divisions.

Important Art by Paula Modersohn-Becker

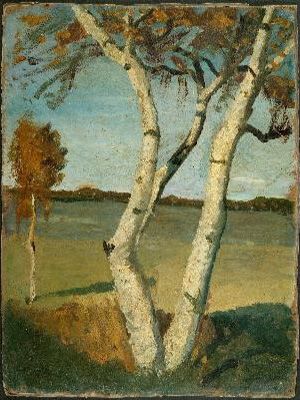

Birch Tree in a Landscape

As the title reflects, a large birch tree dominates the foreground of Paula Modersohn-Becker's early landscape painting. Split at its base - perhaps alluding to divided interests as woman and artist - the tree rises up in two large white columns. Set in the fall season, the leaves are depicted in a vivid orange, and in the background stands another smaller birch in an expansive green field.

The painting is a good example of Modersohn-Becker's early focus on landscapes, gleaned in part from the overarching interest in landscape painting to be found at the artist colony at Worpswede. The focus was particularly strong for Fritz Mackensen, the founder and for the artist's future husband, Otto Modersohn. Thus Modersohn-Becker too chose to depict the simple beauty of surrounding landscapes for a time. Of her first experience with the colony, she later wrote, "...Worpswede, Worpswede, you are always on my mind. That was real feeling to the tip of my tiniest finger. Your mighty grandiose pines! I call them my men, broad, gnarled and large, and yet with fine, fine sinews and nerves. I think this is an ideal artistic form. And your birches, the delicate slender young women, which bring joy to the eye." Here is a similar albeit visual manifestation of these strong grateful feelings expressed towards the wonder of nature.

Interestingly though, as Modersohn-Becker began spending more time in Paris, she became increasingly influenced by modern art. As she became heavily inspired by the work of the Post-Impressionists including Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, her landscapes became looser and more abstract than those by other members of the colony. Indeed, within a few years, Modersohn-Becker moved away from landscapes all together, turning instead to still lifes and then to portraits. Here, however, one importantly sees a full embrace of natural themes, and reveals the artist's clear inspiration from Impressionist artists such as Claude Monet.

Oil on composite board - Collection of Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Still Life with Pumpkins

This Modersohn-Becker still life in classic formation consists of a table with red and white-checkered tablecloth upon which is placed a plate overflowing with oranges, some apples, and a large cut pumpkin.

While best known for her portraits, Modersohn-Becker also created a large body of still lifes, with the most notable similar to this one and completed in the same year. According to art historian Diane Radycki, the artist, "...was only sporadically occupied with still life for the first two years after she quit landscape painting, even though she painted at least one such picture every year.[...Then] [i]n 1905 [...] there was a dramatic increase in the number of still lifes she painted, so much that over the next two years she produced more than fifty of them."

This particular still life importantly highlights the increasing influence of Post-Impressionism on Modersohn-Becker's painting style. Specifically, the compositional elements of the bunched tablecloth and casually placed fruits are reminiscent of the still lifes of Paul Cézanne. Similarly, the loosely but heavily-applied brushstrokes, most notably on the pumpkin flesh itself, also recall the techniques of Cezanne, as well as further revealing the influence of Vincent van Gogh. Evident here, is an artist, who had fully embraced the Paris modernism of which she too was an integral part.

Oil on cardboard - Collection of Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany

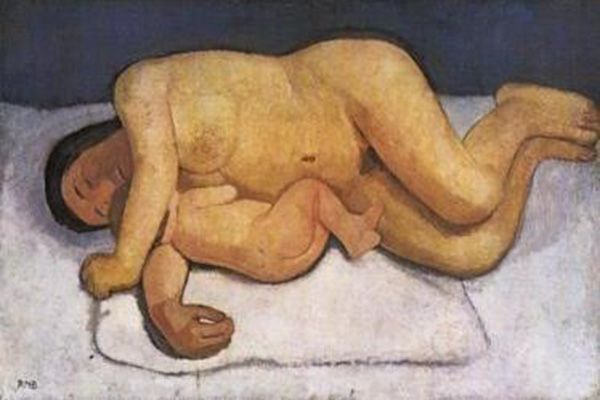

Reclining Mother-and-Child Nude II

As the title describes, in this painting, Paula Modersohn-Becker depicts a naked woman lying in a cradling embrace with her infant. Eyes closed, the mother lovingly protects the head of the naked child with her arm; there is also the possibility that the baby is breastfeeding. This would have been a profound and shocking image at the time that it was created. To expose a new mother and child in such a realistic pose, in utter contrast to previous idealized religious iconography, was a completely invisible experience at the turn of the twentieth century. Indeed, the subject remained very unusual and overlooked until early in the twenty first century, roughly 100 years later.

For the pioneering Modersohn-Becker, she recognized that this was one of the themes through which, as a female artist, she was able to push the boundaries of gender and in turn to empower women through their own everyday experience. Her approach to the long-established tradition of mother and child portraits was primarily groundbreaking in that she depicted the duo in the nude and furthermore, often in moments of simple, innocent, and shared intimacy. Indeed, this is a modern approach to maternity and one that matches the contemporary photographs depicted in Home Truths: Motherhood and Photography (2013), a seminal exhibition on the subject held in London over a century after Modersohn-Becker's similar explorations.

Modersohn-Becker gives no attempt to appeal to the male gaze, nor does she provide an overly-perfected, Madonna-like depiction of a mother and her child. Radycki reasons, "the frank exhibition of the body, from breast to belly to pubic hair, sets this apart from all previous maternities, and points not back but forward. The 'generic motif' for Modersohn-Becker is a decidedly twentieth-century one: the New Woman, envisioned alternately as an emaciated figure or as a gargantuan amazon." She was a trailblazer, a rebel, and a revolutionary painter and human being.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen, Germany

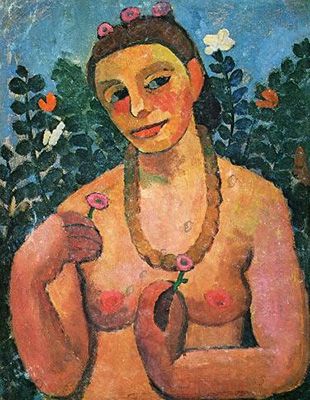

Self-Portrait Nude with Amber Necklace, Half-length I

In this self-portrait, Paula Modersohn-Becker depicts herself from the waist up, in a field of green leaves and white and red flowers. She is nude, with breasts exposed, and she wears a beloved amber necklace, which also appears in other self-portraits. She holds a pink flower in each hand and a further three flowers line the crown of her pulled-back hair forming a Flora-reminiscent, Spring-like crown. Indeed, the flowers form a literal circle around the artist presenting to the viewer the message that she respects nature above all and believes in the cycles that it creates.

While portraits had long been a part of Modersohn-Becker's oeuvre it was not until 1905 (only two years before her death) that she turned to herself as her main figural subject. While there had been a tradition of female artists painting self-portraits, in part because models were so limited for women prior to the onset of modernism, Modersohn-Becker still broke barriers here as she was the first woman to paint herself in the nude.

The colorful and lush backdrop of the painting adds a hint of influence coming from the Tahitian paintings of Paul Gauguin, an artist whom she was known to admire. Interestingly, in this particular painting the artist looks to the side rather than directly at the viewer. She appears happy in an inner world, and it is easy to believe that this is a woman most at peace with her own private pursuits.

Oil on cardboard - Private Collection

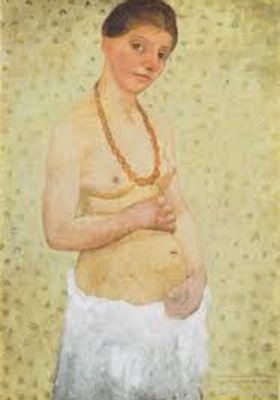

Self-Portrait on 6th Wedding Anniversary

In this extraordinary self-portrait, Paula Modersohn-Becker imagines herself pregnant. As in the previous image - with a circle created by flowers - here the vision of encircling is created by the artist's hands wrapped around her own pregnant belly. Once again she wears her amber necklace and leaves her breasts exposed, whilst this time she looks directly out at the viewer. The image is mysterious in that it presents a fantasy rather than an actual pregnancy; in this sense it opens up the experience for questioning, not simply presenting the state as natural and thus to be accepted and succumbed to. Modersohn-Becker at this time was a practicing artist living alone in Paris; she was discontent with her marriage and likely asking the question as to if she would like to become a mother, and in turn, how the event would change her life.

Many artists more recently have investigated the theme of maternal ambivalence, most notably perhaps Tracey Emin. Emin investigated being pregnant at moments when she was, and at times when she simply longed to be, but was not. Modersohn-Becker's image has further added poignancy knowing that the artist did subsequently become pregnant the following year, only to die three weeks later. This element of tragedy aligns the artist's practice with another artist who revolutionized our view of motherhood, that of Käthe Kollwitz. Kollwitz regularly investigated the bond between mother and child, with her images infused with the foresight of sadness knowing that she would lose a child.

According to the art historian Diane Radycki, having painted herself nude several times, "of all her self-portraits, the most controversial is the one she painted of herself nude, when she was thirty. It makes reference to herself as a woman in the image and as an artist in the inscription: 'I painted this at age 30 / on my 6th wedding day. / P.B." The fact is, as Radycki explains, "Modersohn-Becker rarely signed, titled, dated, or showed anyone her work" but here she did. In so doing, she is asserting her independence; painting a self-portrait at a time that she has left her family (and any sort of conventional life) to pursue a career as an artist. That she signed the painting with the initials "P.B." (Paula Becker) and did not include her married initial further visually supports her decision of what is most important in her life: her career and not her family, or at least not her marriage. In fact according to Radycki, the artist had once stated upon settling in Paris in 1906, "now that I am free, I will make something of myself. I almost believe, by this year.' Thirty was a deadline of particular importance to her, and she said so." In this painting then, she is providing evidence for the entire world to see that she has truly arrived as an artist, having found a subject of great originality to speak revealingly about.

Indeed, the artist has painted herself as if she is pregnant despite the fact that she was not. Until this point, the artist is not known to have shown any interest in being a mother and she introduces the subject ripe with questions and challenges. Whether longing for a child at this point, or metaphorically suggesting that she was pregnant with ideas, the painting exists as an allusive and open-ended statement for our consideration.

Tempera on canvas - Collection of Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen, Germany

Old Peasant Woman with Arms Crossed on Her Chest

An old woman dominates this late painting by Paula Modersohn-Becker. Plainly dressed in a blue long-sleeved frock and white cap, the woman stares vacantly out in front of her with her arms crossed upon her chest. The gesture appears somewhat religious and her attire suggests that the woman is poor. Set against a green leafy background, the only other burst of color can be found in three small yellow flowers resting on the sitter's lap. In many respects, the portrait is very close to the work of Vincent Van Gogh. Van Gogh was always attracted to the humanity of the working classes and had a tendency to elevate their position by way of introducing illuminating light sources and had a similar focus on large toiling hands in his paintings. It is even arguable, that Modersohn-Becker includes yellow flowers in her painting to make clear that the image is done in homage of Van Gogh.

Once Modersohn-Becker had begun to paint portraits, she embraced her new genre with great intensity. This work is arguably one of the finest examples of one of her main model types, the old peasant women. While living in Worpswede, Modersohn-Becker was able to find models such as this lady in abundance living in the village poorhouses. Here, as in all her portraits featuring these occupants, she captures most prominently the sitter's individual serenity despite their reduced and often troubled circumstances. According to the museum text written by the Detroit Institute of Art, "this image of an old woman is given dignity by the reduction of the subject to simplified large forms and by the harmony of color, to reveal the inner meaning of her subject. Her gesture, traditionally used in depictions of the Annunciation as Mary's acceptance of her role, here can be interpreted as the old woman's recognition of her place in the cycle of human life and is underscored by the flowers in her lap."

Notably, the portrait shows the maturity of Modersohn-Becker's figural style. While she had often incorporated flowers with her female portraits, whereas others often show women in fields of flowers, here the simple cluster of flowers serve to illuminate the sharp contrast to the drabness of the peasant's clothes and even more so, her life. According to art historian Diane Radycki, "there is the coarse peasant and the delicate yellow posy that her rough hands picked and placed so strategically on her lap (or, for that matter, the three little yellow buttons on her jacket that those gross fingers had buttoned)." Basically, it is imperative to remember that there is great beauty and harmony to be gleaned from this woman despite her struggles. Rendered in an expressionist style, the work shows the artist's later approach to color in which she left behind an earlier, at times somber, color palette and rendered instead a more moving portrait in rich contrasts of blue, green, and yellow hues.

Oil on canvas - Collection of The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan

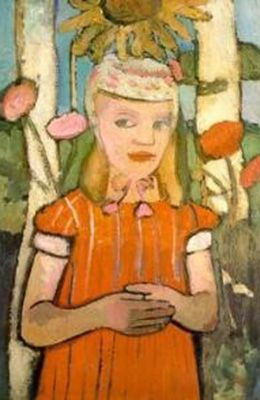

Girl in a Red Dress Standing Under a Sunflower

A young girl is the focal point of this Paula Modersohn-Becker painting, interestingly again with her hands acting as a central feature of the work. Hands appear to convey two messages for the artist. The first, that she is interested in all that is "hand made" and in a life dedicated to individual creativity, whilst a secondary suggestion, that hands brought together offer a spiritual aspect is also made. Blonde-haired and blue-eyed, the girl wears a red dress and white and pink bonnet. Her hands are clasped in front of her slightly above her waist and she glances out to her left as though to something beyond the confines of the canvas. Positioned in a field of pink and red flowers, directly behind the girl there is a large sunflower and two white birch trees. We now witness a style, which although inspired by the linage of Post-Impressionism, is steadily becoming the artist's own.

Painting young girls, by contrast to her older ladies, was another popular subject for Modersohn-Becker. She was interested in the progression of girlhood through to womanhood and in the different challenges encountered along the way. Whilst many of her portraits of girls were somber in nature, featuring the peasant children living in the community of Worpswede, here she took a more direct and personal subject, that of her stepdaughter, Elsbeth. The work serves as a fine example of the expressionistic style, which Modersohn-Becker had near perfected towards the end of her tragically short career. Here in this painting the artist includes, as described by art historian Diane Radycki, "...a bright palette, thick brushwork, and simplified shapes" and also notably a figure with, "...no room to move, despite being outside: she is right up to the picture plane, with no deep space behind her."

Perhaps at this point in her life, having returned to Worpswede to live with her husband and Elsbeth, Modersohn-Becker finally feels more of a closeness to her step-daughter as signified by being the child being brought so far forward on the picture plane. While having been in her stepdaughter's life since she was two-years-old, it seems that only here many years later that she first acknowledges the deep love that she feels for this child. The painting may also have been made simultaneously in homage to her cousin, for according to Radycki, "the artist had been but a year older than her stepdaughter when she saw her eleven-year-old cousin suffocate in a sand pit." Of this event, Modernsohn-Becker said later of her cousin, "You are my legacy" and indeed that all art that she was to produce during her career was in someway made in dedication and homage to this lost child.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

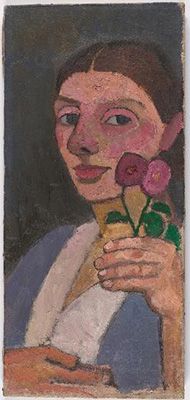

Self-Portrait with Two Flowers

In this half-length self-portrait, Paula Modersohn-Becker depicts herself in a blue dress and white collar. Her right hand rests on her stomach, which is distinctly swollen in pregnancy. In her left hand she holds up two pink flowers directly towards the viewer. One of the flowers is bright and illuminated whilst the other is darkened and in shadow. Similar to the artist early split birch tree, the stem splits to suggest multiple possible meanings.

According to art historian Diane Radycki, "she holds up two flowers that she thrusts right at the viewer [...]. She is insisting on the creative woman's twin gifts: her genius and her biology." It is indeed a possibility that the artist seeks to comment on the tension that a woman feels between following a chosen career and devotion to motherhood. Equally, however, the two flowers could signify mother and child. The image successfully makes visible the feeling of carrying another being inside, that of at once being separate and connected at the same time.

The shadow upon one of the flowers could indeed be a sad foresight towards Modersohn-Becker's impending death, whilst her child (the other flower bathed in light) would live on as her legacy along with her paintings. Profound and groundbreaking, overall the work occupies an important place in the history of art. Painted whilst actually pregnant (having already made her 'fantasy' pregnancy image the previous year), this artwork is the first self-portrait to feature a woman in this condition, real and un-idealized. Interestingly, although unsure of impending motherhood when she first found out that she was pregnant, during this the final trimester, Modersohn-Becker no longer feared the demands a child would bring to her career, and instead fully embraced the experience. She became especially creative and tirelessly productive during the final phase of her career.

Oil on canvas - Collection of The Museum of Modern Art and Neue Galerie, New York, New York

Biography of Paula Modersohn-Becker

Childhood and Education

Paula was the third of seven children born to parents Carl Woldemar Becker and Mathilde Becker. While her parents were strict and often demanding, they were also interested in art and culture; so when Modersohn-Becker showed an early proclivity towards art, her parents encouraged it. According to art historian Diane Radycki, her mother even "...took in a boarder in order to pay for her daughter's art lessons."

Modersohn-Becker's childhood, while generally happy, was marked by a series of losses including the death of her infant brother and both grandfathers. The most traumatic of these losses however, occurred at the age of ten when she witnessed the death of a beloved eleven-year-old cousin while they and a group of other children were playing near a sand pit. Her cousin fell into the pit and suffocated to death. The impact of this was later described by the artist, as, "at the moment of her death, Maid [a sister of the victim] and I hid our heads deep in the sand in order not to see the terrible thing we knew was happening. I said to her then, 'You are my legacy.' And so she has remained." It can be reasoned that later, when she became an artist, it was this tragic event that inspired her many paintings of children.

Early Training

An introduction to formalized art training began for Modersohn-Becker at the age of sixteen when she went to stay with her aunt and uncle in London where she was able to enroll at St. John's Wood Art School. Although her difficult aunt, homesickness, and the development of severe headaches led to her returning home after only a few months, her interest in art had been firmly established. Once home however, her parents were desperate for her to learn a trade through which she could support herself and therefore insisted she attend a two-year program to train to be a governess. Modersohn-Becker consented but during the course she simultaneously took further art classes and integrated with local artists.

After completing her governess training, Modersohn-Becker convinced her father to send her to art school in Berlin. While he only initially consented to a two-month stay, she ended up studying at the Drawing and Painting School of the Association of Women Artists for two years. The education she received enabled her to hone her natural skills. It was also importantly at this time, while on breaks from school, that she began to make visits to the artist colony in Worpswede, Bremen, Northern Germany. Greatly impressed by the work of the artists living there, after finishing school in the fall of 1898, she convinced her family to let her move to the colony to study with its' founder Fritz Mackensen. While this would change over the years, she was initially greatly attracted to the colony and to the shared focus there on nature and landscapes. It was also here that she would meet her future husband, colony artist Otto Modersohn, as well as a cohort of friends and fellow artists including Heinrich Vogeler and Clara Westhoff.

Eager for more formal artistic training, in January 1900, Modersohn-Becker left Worpswede to study in Paris. Significantly, this trip would mark the beginning of a lifelong pattern of time spent moving between the two locations, Paris and Worpswede. Once settled in Paris this time around, she enrolled in classes at the Académie Colarossi and the École des Beaux-Arts. It was here that she focused on life drawing and developed her passion for nude figure studies, already a longstanding interest. Of this time she stated, "afternoons I draw from the nude at the academy. Every half hour a new position. I love doing that."

Mature Period

The summer after her first extended stay in Paris, Modersohn-Becker returned to Worpswede where she met the influential writer Rainer Maria Rilke, and the two built a strong albeit sometimes complicated friendship. It was also during this time that she became engaged to Otto Modersohn. As one of the original founders of the art colony, he was a dedicated landscape painter preferring the plein air approach to painting of the Barbizon School. His wife had died only three months before he proposed to Modersohn-Becker, leaving him at the time a widower with a two-year-old daughter. Whilst Otto would offer her some desperately needed financial security ending the worries of her parents regarding their daughter's future, there is little to support that Modersohn-Becker was otherwise particularly keen to agree to this marriage or to settle down. Shortly after her engagement, for instance, she spent the early months of 1901 in Berlin where she took cooking classes (under the instruction of her father to relinquish her ego and become a good wife) and spent time with Rilke. Still, on May 25 she married Otto, one month after Rilke and her best friend Clara Westhoff were also married.

Modersohn-Becker did not take easily to marriage, which, how hard to believe, was said to remain unconsummated for several years. Her struggles are supported in a diary entry in which she wrote, "I have cried a lot in my first year of marriage...I feel as lonely as I did in my childhood....It is my experience that marriage does not make one happier. It destroys the illusion that has been the essence of one's previous existence, that there existed something like a soul-mate." She also recorded in diary entries that when at home, she was happiest in Otto's absence, for only then she could live off pears and rice pudding, didn't have to set the table, could read over her food, and basically felt much freer.

Perhaps in part to escape her marital disappointments, whilst simultaneously to advance her career and to pursue a feverish need for independence, as a newlywed Modersohn-Becker continued her solo trips to Paris (6 in total) during which time she painted, studied master works in museums, visited salons, and became increasingly engaged in modern art and artists such as Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin. It was also during this period, as a result of her friendship with Rilke, that Modersohn-Becker would have the opportunity to interact with great artists. Rilke had worked as a secretary for Auguste Rodin as he had intended to write a monograph on his work. Indeed, he did complete various extended essays and deliver lectures on Rodin. Rilke, thus introduced her to Auguste Rodin. Modersohn-Becker also met Picasso because of Rilke's connections, but she herself also knew many practicing artists as she often took courses at the École des Beaux-Arts and made sure to visit all of the current exhibitions when she was in town.

While staying in Paris, Modersohn-Becker wrote to Otto stating that she missed him as well as Worpswede, and asked her husband to send money. Although he consented and continued to support his wife financially, Otto was grieved by her absences of which he stated, "her feeling for family and home is weak. I do hope it will grow." In truth, it was clear at this moment that her desire to be an artist came first above all other interests and responsibilities.

Later Period

The paintings created during the last years of Modersohn-Becker's short career show a deep embrace of modern art and all the influence and knowledge that she had gleaned from time spent in Paris. She moved entirely away from the classic landscape and nature themes championed by the colony artists of Worpswede and focused heavily on still life and portraiture. More than fifty of her later portraits were notably of nude figures.

The instability of the blossoming artist's family situation did not improve the longer she was married. Despite often returning to Worpswede to paint and be with her husband and stepdaughter, Modersohn-Becker constantly longed for Paris and to immerse herself wholly in the artist's life. The urge finally completely overtook her in the middle of the night in February 1906 when she fled Worpswede for Paris without telling anyone.

Modersohn-Becker thrived during this time alone in her beloved city of which she stated, "I am becoming something - I am living the most intensely happy time of my life." After setting up a studio she enrolled in more classes, spent time with friends including Rilke, and painted her first nude self-portrait. No one, it seems was able to entice her to return to Worpswede including her mother to whom she wrote, "now I am beginning a new life. Don't interfere, just let me be." At this moment in her career, Modersohn was working prolifically, producing 80 significant pictures in just one year.

Her husband, unhappy at his wife's actions, but without the ability to convince her to return home, would sometimes visit. These interludes, however, appear to have been largely unwelcome as Modersohn-Becker did consult a divorce lawyer while in Paris. She never went further along this path however, perhaps in no small part because she remained fully financially dependent on Otto. Interestingly, whilst Otto had initially been a great supporter of his ambitious wife's work, by this point he had grown weary of her great need for freedom and spitefully wrote of her paintings made at the time, they are "ugly, bizarre, wooden ... mouths like wounds, faces like cretins. A revolting mixture of colours, of idiotic figures, of sick children, degenerates, the dregs of humanity"".

However, still in love and in an effort to save their marriage Otto moved to Paris in October 1906 to be with Modersohn-Becker. This would have meant a dramatic change in their relationship and yet the need for money led the conflicted artist to accept. According to Radycki, "with Otto in Paris, she could expect a consummated marriage and the possibility of motherhood, as well as money to pay the studio rent, buy good painting supplies, and hire models...."

During this time in Paris, Modersohn-Becker's career began to take off. Her work was included with other Worpswede artists in a Bremen exhibition, which then traveled to Berlin. This event marked the second time that her work was publicly shown, and she received reviews full of great promise.

Unfortunately however, a lengthy career was not possible for Modersohn-Becker. In March of 1907 she became pregnant and returned with Otto to Worpswede. It appears that the artist struggled to come to terms with the demands that impending motherhood could have on her career. According to Radycki, Modersohn-Becker, "...had long struggled with her desire for motherhood, and just as long had she chosen not to act upon that desire." In one letter she wrote while pregnant she stated, "I have worked so little" and in another to her sister she begged, "never write me another postcard with the words 'diapers' or 'blessed event' on it. You know full well that I am a soul who prefers that other people not know that she will be busying herself with diapers."

Still, near the end of her last trimester, Modersohn-Becker seemed to become artistically inspired and wrote, "I am painting again and would that I had an invisible cloak, I'd push on ever so longer and farther." At the time, she painted Self-Portrait with Two Flowers (1907). While personally symbolic in that it revealed to the artist herself that motherhood would not end her desire or her ability to make art.

While pregnant, Modersohn-Becker still longed for her life in France. Radycki describes how she wanted to see an exhibit of Paul Cézanne's paintings that were then on view in Paris in October 1907 and wrote to her friend Clara, "if it were not absolutely necessary for me to be here, I would have to be in Paris." That was not to be however, as on November 2 Modersohn-Becker gave birth to a baby girl she named Mathilde after her mother. According to Radycki, while the labor was difficult, when her friend Clara visited the new mother she recalled how she seemed happy and described how, "the smiling artist kept saying of her healthy newborn, 'You should see her in the nude!' Mother and child [...equals] artist and nude model."

Modersohn-Becker began to experience strong pains in her legs only a week after labor and was ordered to two weeks of bed rest. Perhaps in a foreshadowing of her own end, Radycki writes on how, "in the last letter she wrote, the artist declared, 'I'm not afraid of anything, everything will go well - only death, now there is the ghost that frightens me, that is the one real misfortune." Modersohn-Becker, at the young age of thirty-one, succumbed to complications of pregnancy eighteen days after giving birth. She had been instructed by her physician to remain in bed, likely causing a fatal postpartum embolism.

The Legacy of Paula Modersohn-Becker

Paula Modersohn-Becker was the first woman artist to paint herself nude and furthermore, the first artist to paint herself nude while pregnant. Her repeated themes of moving self-portraits and portraits of women and children are well integrated within the foundations for the Feminist Art movement. She has had great influence on the work of contemporary female artists dedicated to similar subject matter, including most notably Frida Kahlo, Tracey Emin, and Cindy Sherman. Another contemporary artist, Jenny Holzer, wrote specifically of the artist's influence on her practice, stating, "I became aware of Modersohn-Becker when I was young, and loved her work for its subject, its gravity and its success. I was encouraged and frightened by her story. Not many women were serious artists, as well as mothers. Not many artists treated motherhood without sentimentality, or without showing a mother and infant in service of religion. I suspect I had Modersohn-Becker in the back of my mind when I began the Mother and Child text for the Venice Biennale."

In describing her legacy, art historian Diane Radycki asserts, "today, post-Guerrilla Girls and post-modernism, Modersohn-Becker's risk can escape us, used as we are to frank sexual images. Her female bodies defy the idealized and eroticized nude, and at the same time destabilize Self-Portrait, Children, and Mother and Child as minor genres in the hierarch of painting categories. Modersohn-Becker shifted paradigms that, over course of the twentieth century, continued to change with the person and the practice of the woman artist."

In yet another "first", Modersohn-Becker was also the first female artist to have a museum constructed and dedicated entirely to her work. The museum was commissioned by forward thinking arts patron, Ludwig Roselius who invited innovative sculptor and architect, Bernhard Hoetger to design the building. Hoetger had been a personal friend of Modersohn-Becker, and the museum opened in 1927. It came under threat by Hiltler and his Degenerate Art designation but luckily avoided demolition and is still open today - the building itself being one of the key works of Expressionist architecture in Germany - housing the largest collection of paintings by Modersohn-Becker. Although the building survived, Modersohn-Becker was still featured as a rare female artist included in the list of leading modernist artists that Hitler condemned as too dangerous to be viewed by the German public in 1937. Thus whilst not overly recognized in her lifetime, her impact as an important modernist artist and the power of her work was significantly confirmed mere decades after her death by its inclusion in this infamous historical exhibition.

Influences and Connections

-

![Paul Cézanne]() Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne -

![Paul Gauguin]() Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin -

![Auguste Rodin]() Auguste Rodin

Auguste Rodin - Fritz Mackensen

- Otto Modersohn

![Emile Nolde]() Emile Nolde

Emile Nolde![Rainer Maria Rilke]() Rainer Maria Rilke

Rainer Maria Rilke- Jeanna Bauck

- Marie Bashkirtseff

- Gustav Pauli

-

![Expressionism]() Expressionism

Expressionism -

![Impressionism]() Impressionism

Impressionism -

![Les Nabis]() Les Nabis

Les Nabis -

![Post-Impressionism]() Post-Impressionism

Post-Impressionism - Japanese art

-

![Jenny Holzer]() Jenny Holzer

Jenny Holzer - Rineke Dijkstra

- Otto Modersohn

- Heinrich Vogeler

- Clara Westhoff

![Emile Nolde]() Emile Nolde

Emile Nolde![Rainer Maria Rilke]() Rainer Maria Rilke

Rainer Maria Rilke

Useful Resources on Paula Modersohn-Becker

- Being Here is Everything: The Life of Paula Modersohn-BeckerBy Marie Darrieussecq

- Paula Modersohn-Becker: The First Modern Woman ArtistOur PickBy Diane Radycki

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI