Summary of Nadar

Nadar was a flamboyant personality and a man of infatigable spirit. A writer, caricaturist, inventor and adventurer, yet still best known perhaps as a celebrity portrait photographer, he placed himself at the very epicenter of nineteenth century French modernism. In addition to his satirical caricatures, Nadar produced (and sold) informal "inner-life" portraits of the new literati from his landmark studio-cum-gallery, a site from which, the Impressionist also launched their inaugural public exhibition. Restricted by the studio, Nadar took to the under and above ground to expand his photographic repertoire, patenting aerial photographs for mapmaking and surveying, and taking his handmade electric light underground to illuminate his unique photographs of the famous Paris catacombs. Though his entrepreneurial spirit led to several setbacks, Nadar nonetheless set commercial (in addition to aesthetic) precedents for the reproduction and hawking of his superior celebrity portraits.

Accomplishments

- Nadar made his name initially as a satirical writer, critic and caricaturist. Like his esteemed circle of friends, he viewed the development of modernity through analytical eyes and delivered his stinging verdicts on the political classes through the satirical press.

- Once established as a portrait photographer, Nadar set about creating a celebrity culture for nineteenth-century Paris. Through his connections with the pioneers of French modernism, and with an affable manner that earned their complete trust, he was able to produce informal and engaging portraits of his famous sitters that he sold on to the public in unprecedented numbers.

- In his desire to move photography out of the studio, Nadar invented a portable electric lighting system. His ingenuity allowed him to take his camera down into the famous Paris catacombs. Off limits to the general public, Nadar was able to evidence something of the scale of the sprawling underground crypt for the first time.

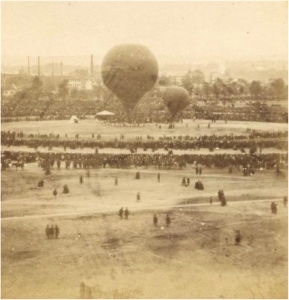

- Having revealed something of subterranean Paris, Nadar took next to skies in hot air balloons to offer a bird's-eye view of his great city. Though his aerial adventures were fraught with complications and dashed dreams, he can still be credited with producing the world's first successful aerial photography.

Important Art by Nadar

Drawings from "Lanterne magique des auteurs et journalistes," Le Journal pour rire

In this early caricature, a succession of men and a dancing harlequin march toward the mythical Mount Parnassuss (Montparnasse is also the name the Parisian arrondissement). With small bodies and large exaggerated heads, the group moves across the page from right to left. The figure leading the way, his followers quite literally "hanging on to his coattails", is the Romantic writer Victor Hugo (author of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame). The text below the caricatures includes witty commentary and anecdotes about the figures (some even provided by the subjects themselves). Published in Charles Philipon's satirical Parisian newspaper, Le Journal pour rire, this caricature is part of a series entitled Lanterne magique commenced just two months after the ban on political caricature was instituted by Louis-Napoléon (Napoléon III) in late 1851. With political satire no longer an option, Nadar looked to contemporary society and its fascination with the new crop of writers, poets, artists, and intellectuals. Each installment of the series included a strip with five or six caricatures arranged one after another as if on a slide to be projected in a magic lantern (Lanterne magique).

A common form of entertainment in the 19th century, the magic lantern projector was also used as a tool for educating the public. Like the magic lantern show to which it refers, Nadar's Lanterne magique illuminated the cultural milieu of Second Empire Paris. As scholar Adam Begley put it, "implicit in the conceit [...] is the parallel between the way a magic lantern enlarges an image on a slide and the publicity generated when a newspaper prints a successful caricature of a public figure. In short, Nadar was operating a machine for magnifying the exposure of celebrities." Although early installments included writers and journalists, later iterations featured artists, musicians, and other prominent men. Published over the course of a year, the procession of important cultural figures, always in the same oblong, sequential format, included some three hundred figures.

Nadar's Pantheon (Panthéon Nadar)

Led by Victor Hugo, a group of 250 writers, including Nadar himself (seated behind a sign in the second row from the top), are pictured marching downward where they come to stop in front of the busts of storied Parisian writers, François-René de Chateaubriand, Honoré de Balzac, Frédéric Soulié, and George Sand. Building on his previous work, Nadar's Pantheon was a large-scale group portrait that would include nearly one thousand prominent Parisians. According to writer Maria Morris-Hambourg, it was intended to "mirror the contemporary scene more completely than all the existing galleries, museums, and biographical collections of illustrious contemporaries." Morris Hambourg added that "At this moment, when the press had promulgated the fame of the individual far beyond his immediate circle, when romantic notions of the heroic artist had become the heritage of a newly mass public, and when Paris reigned as the capital of the cult of personality, the project of a grand and clever portrait gallery of the great was exactly apropos."

Bringing together original and existing caricatures, and a compilation of biographic and anecdotal materials, the completed work was presented on a single sheet measuring approximately 32 x 45 inches. The enormity of the task was more than Nadar could manage or afford on his own. In fact, it took nearly two years to complete what was the first of two enormous lithographs (he in fact had planner for four). At a subscription price of 7.50 francs (or 12 francs after publication), the Pantheon appeared in shops with much fanfare in March of 1854. It was a huge success, selling in vast numbers in the first six months, and Nadar became an instant celebrity. If his Pantheon was intended to capitalize on Paris's cult of personality, he had indeed joined their ranks. Despite the success of the first installment, however, the project produced only a modest financial windfall. By the time he paid the small army of people involved in the Pantheon's production, and due to copyright complications that saw the work withdrawn from sale, the Pantheon was not the financial success it should have been. It was clear that Nadar would not be able to raise the necessary finance for the remaining three installments though he did produce a second Pantheon made of existing and new photographic portraits including those of Gustave Doré, Charles Baudelaire, Théophile Gautier and Eugène Delacroix.

Lithograph - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Nadar and Adrien Tournachon, Pierrot Running

In this image, Pierrot, a well-known mime, dressed in his iconic flowing white costume and white face makeup, appears still, as if caught in mid-stride. A play on the exaggerated poses typical of a mime's performance, but also the extended stillness required for the long exposure, Pierrot Running is one of a series of photographs of the famous mime that feature a range of dramatic poses and facial expressions. Taken with a large format camera Nadar purchased for Adrien's studio, many of the photographs from the series are remarkable for the size of their scale (8 ¾ x 8 ½ inches). The full-length portraits were intended to take full advantage of the large paper. Pierrot, Charles Debureau, son of Baptiste Debureau, the famous mime who performed at Théâtre des Funambules, would have been familiar to Parisian visitors. French editor and critic Ernest Lacan, in his famous passage on Nadar, spoke of their presence at world's fair (the 1865 Exposition Universelle) : "But amidst all these examples, those that have most aroused the interest of the public, those that few viewers have passed without stopping, are the Pierrots [. . .] Each of these prints is an admirably rendered study of expression [. . .] There are, under the comical exterior of these specimens, great difficulties overcome and beneficial results for art."

There is some question regarding whether or not this particular series of photographs can be attributed solely to Nadar or to his younger brother, Adrien. Having set his brother up in a photography studio in 1854, the two collaborated for period between 1854 and early 1855 and the photographs of Pierrot were part of a publicity campaign intended to spur interest in the new studio. The photographs of Pierrot were exhibited at the world's fair held in Paris in 1855. Although the photographs of Pierrot were a collaborative effort between Nadar and his brother, when they won a gold medal at the Exposition the credit was given to Adrien who went under the name "Nadar jeune" ("Young Nadar").

Albumen silver print from glass negative - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Charles Baudelaire

In this seated portrait of Charles Baudelaire, amongst the most iconic of the legendary poet, novelist and essayist, Nadar depicts his friend in a casual pose with one hand at his face and the other clutching a cut of white cloth as he looks toward the camera. Nadar had met Baudelaire in 1842, which he later described in his book Charles Baudelaire intime (The Private Baudelaire). "Suddenly our conversation stopped, halted by the sight of a strange, ghostly figure [. . .] We saw a young man of medium height with a good figure, all in black except for a russet scarf, his coat scrupulously cut, excessively flared with a roll collar from which his head emerged like a bouquet from its wrappings [. . .] In his hand in its pale pink - I repeat pink - glove, he carried his hat, made unnecessary by the superabundance of curling, very black hair that fell to his shoulders - a mane like a waterfall. So we were going to meet him, this much awaited figure, this supreme attraction!"

This early portrait was taken not long after Nadar separated from his brother's photography studio and began inviting his friends and family to sit for their portraits in his home on rue Saint-Lazare. He was most interested in these early portraits with putting his subjects at ease rather than produce the stiffly posed portraits that characterized early commercial portraiture. From the comfort of his sitting room, Nadar was better placed to produce more intimate portraits of his fellow artists and writers. These were rarely commissioned portraits, many paying only a fraction of the fee charged to wealthier clientele (typically 100 francs). As Maria Morris Hambourg has noted, "warmed with past memories and mutual regard, old friends naturally responded to Nadar's seductive energy, his jokes, his endearing stories, his complete attention. They participated in the performance, returning his concentration and trust. In such encounters with the members of his chosen family, it would not be too much to say that Nadar gave himself over to love."

Salted paper print

Catacombs, Paris

One of a series of over one hundred photographs Nadar took in the catacombs deep below the streets of Paris, the image shows row-upon-row of human skulls. Despite a complete lack of natural light, the long passageway on the left is clearly illuminated. And as the handwritten note at the bottom of the photograph attests, Nadar made the photograph with the help of a magnesium lamp of his own invention. The bright light in the background of the image draws the viewer in, giving us a sense of the depth and scale of the "cities of the dead" that sprawled beneath the feet of Parisian city-dwellers.

Opened in 1810, the catacombs were brought into use due to increased concerns over overcrowded cemeteries in Paris. To remedy the situation, city officials transformed former underground quarries to house skeletons. It is said that nearly six or seven million skulls lined the walls of the catacombs. Despite its macabre associations, the catacombs were an instant attraction for both artists and the inquisitive onlooker. Although it was officially closed to the public in 1830, artists like Nadar still found ways to gain access. Nadar once noted that it was "one of those places that everyone wants to see and no one wants to see again." and his photographic reproductions were a hit with the public. Already known for his unusual and surprising images, Nadar took his camera to places never before seen by the Parisian public. Meanwhile the catacombs project proved the perfect vehicle for demonstrating the possibilities for photography aided by electric light.

Albumen silver print from glass negative - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sarah Bernhardt

In this portrait of Sarah Bernhardt, Nadar poses the actress against a simple dark backdrop, with her arm resting on a column that reaches just above waist height. Carefully composed and staged, the twenty-year old Bernhardt - still only on the cusp of international stardom - is swathed in billowing velvet fabric. One of a series of photographs, Bernhardt glances to her side (in others she looks straight into the camera) while Nadar uses his camera to emphasize the young actress's face and flowing dark hair. She appears deep in thought which thus illustrates Nadar's desire to explore "the psychological side of photography" through portraiture.

Taken after Nadar's move to a large studio on the boulevard des Capucines (in 1860), the portrait reveals the elements that became the signaturesof Nadar's mature portraits: namely the column as a prop for the sitter to steady themselves, and the use of frontal artificial lighting set against a neutral backdrop. Although Nadar is said to have been on hand to personally oversee Bernhardt's sitting (by this time he was often out the studio and left the day-to-day operations to assistants), the photograph makes clear that he had standardized his studio's approach to portraiture. The casual rapport he established with his famous sitters transcended the formal pose that had characterized studio portraiture hitherto. Moreover, Nadar's photographs of celebrities like Bernhardt were part of a larger commercial strategy that was unprecedented in the nascent field of photographic portraiture.

Albumen silver print - J. Paul Getty Museum

Biography of Nadar

Childhood

The first child of Thérèse Maillet and Victor Tournachon, Nadar was born with the name Gaspard-Félix Tournachon in Paris in 1820. Nadar's father was a printer and publisher from a prominent Lyonnais family of merchants and printers. An intelligent and liberal-minded man, Victor ran a moderately successful publishing company in Paris' Latin Quarter, publishing a range of titles in French, English, Italian, Spanish, Latin, and Greek. Due to the political nature of certain volumes, Victor's firm was often watched by government censors.

Félix, as he was then known, attended school in Paris near his family home. In 1831, he was sent to a school in Versailles, where he won numerous college stipends. On the back of a scholarship, Félix attended the Collège Bourbon between 1833 and 1836 but he struggled with the pressures of balancing academic work and family obligations. By 1836, Félix, who had developed a keen interest in Romanticism and the literature of Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and Alfred de Vigny, had published his first piece of creative writing. However, his parents had recently returned to Lyons due to Victor's deteriorating health. Abandoned by his family, Félix became an unruly student and was expelled from the school and his lodgings.

Félix returned to Lyons after his father's death in the summer of 1837 and soon enrolled in medical school. He supplemented his academic work by writing theater criticism for the local press. Uninspired by this work, however, he left the provincial city of Lyons for Paris the following year. Once back in Paris, Félix resumed his medical studies, auditing courses at the Hôtel-Dieu and at Bicêtre in Gentilly. Yet despite his keen interest in the field of medicine, Félix failed to gain the necessary qualifications to continue with his studies and was ultimately forced to give up on that career. Without a profession or family support, Félix lapsed into the riotous antics of his earlier youth. It was during these years that he abandoned his given name (Félix Tournachon) for a new, less bourgeois, name: Nadar. Having created their own language as adolescents, Félix and his friends idly created new words and names by adding the letters "dar" to the end of said word. "Tournachondar" was thus shortened to Nadar.

Early Training and Work

In the decade between 1838 and 1848, Nadar lived a bohemian existence, moving frequently from one Parisian dwelling to the next. In order to support himself, he worked odd jobs that included drawing caricatures and writing articles and stories for small newspapers. He even found time to publish a novel. Nadar was starting to become well connected and among his circle of friends was writer and poet Henri Murger, whose La Vie de Bohème (Scenes of a Bohemian Life) (1851), detailed the frivolous exploits of the group (the life-style that Murger described were later popularized in Puccini's famous 1895 opera La Bohème).

Nadar also found employment as a pasteup artist designing page layouts for the Journal des dames et des modes until it ceased publication in 1839. Shortly thereafter - and still aged just nineteen - Nadar founded an ambitious new literary journal, Livre d'or (Golden Book), with painter and engraver Léon Noël. Though they only published a total of nine issues, the journal led to new friendships with Alexandre Dumas and the Romantic poets Théophile Gautier and Gérard de Nerval. Due to the journal's precarious finances, Nadar was compelled to continue writing theater reviews for the independent press. The theaters he frequented during this period included both traditional theatrical productions and vaudeville acts that promoted a form of satirical comedy that thrived during the bourgeoise reign of Louis-Phillipe - known otherwise as the July Monarchy - between 1830-1848.

Throughout the 1840s Nadar associated with an anomalous group of writers and artists. Among them, Charles Baudelaire and Gustave Courbet, became lifelong friends. Gregarious and open to the new wisdoms of modernism, Nadar's widening circle of friends functioned as a second family. As diverse as the group was, they were united in their belief in the freedom of the self and self-expression. However, Nadar's bohemian lifestyle, which meant he neglected to pay rent and other outstanding debts, landed him in debtor's prison in 1850. The experience changed him and later found its way into his writing. Nadar became increasingly drawn to political activism and began using his writing to express his views about the perceived injustices facing contemporary Parisian society. With a growing desire to communicate directly with the public, he began contributing written work and drawn caricatures to antiestablishment newspapers in 1846.

An astute social and political observer, Nadar's turn toward caricature was the logical progression from his interest in satirical writing. Subversive drawings of events and individuals from politics and culture had come to prominence in the years following the 1789 Revolution before becoming truly popularized in the 1830s by the caricaturist Honoré Daumier. The satirical press put caricatures front and center in their publications, and although their primary purpose was to illustrate written articles, the written text came to occupy considerably less space that the illustrations. Within a year Nadar had published some sixty caricatures of notable intellectuals and friends for the satirical publication Journal du dimanche. These eventually made their way into Charles Philipon's Le Charivari, the most famous satirical newspaper in Paris.

A revolution broke out in Paris in February 1848 (known indeed as the "February Revolution"), yet despite his radical tendencies, Nadar did not take to the streets. Instead, he wrote a play that acted out the issues brought about the Revolution - namely, the needs of the working classes and the right for unfettered public assembly. After the Revolution, however, Nadar and his younger brother, Adrien, signed up as volunteers when the new provisional government sent expeditionary forces to help liberate Poland in their fight against Russia. Once in Poland, they were arrested (the military exercise having failed) and forced to work in coal mines until they were freed some months later.

Once safely returned to Paris, Nadar resumed his writing; publishing articles, and working as a copyeditor. He also continued to produce caricatures and comic strips lampooning politicians and leaders, and generally highlighting social ills, for La Revue comique and other satirical papers run by Charles Philipon. Between 1849 and 1862, Nadar established a veritable factory for the production of caricatures. Employing a team of artists, draftsmen, and assistants, Nadar's studio supplied hundreds of drawings that were translated into prints (by wood or lithography), then printed in satirical newspapers (Le Journal pour rire, Petit Journal pour rire, and Journal amusant) and small books or pamphlets. Unfortunately, Nadar was not the best draftsman or businessman and his studio faltered. Nevertheless, the assembly-line mindset proved to be excellent preparation for his foray into photographic portraiture.

Nadar's tendency toward political satire and caricature was curtailed to some degree by the censorship imposed under the newly formed Second Empire, which replaced the republic in 1851. His work shifted from overtly political in tone to caricatures of social customs, the salons and Parisian celebrities. In 1852 he produced the satirical work Lanterne Magique (Magic Lantern), which sought to illuminate prominent literary figures through caricature and accompanying texts with pithy anecdotes. The following year, seeking to build on this success, he began a grandiose large-scale work, called Panthéon Nadar (Nadar's Pantheon), that included some 250 caricatures of prominent Parisian authors. The project proved time-consuming, and while it proved a critical success, it did not help Nadar's dire financial situation. Indeed, Nadar was forced by circumstance to move in with his mother (and her numerous family pets) and his brother (Adrien) to a new apartment in 1853.

Mature Period

Though still a prolific caricaturist, a friend suggested to Nadar that he, with the help of Adrien, open a photographic studio in Paris. Photography, still in its infancy in the early 1850s, was proving to be a lucrative business opportunity for those entrepreneurial individuals willing to invest in the new technological medium. Initially, Nadar did not pursue photography as a practice, however, though he did recognize the financial possibilities of opening a portrait studio. He rather convinced Adrien, himself a struggling portrait painter, to take photography lessons with painter-cum-photographer Gustave Le Gray. With the financial backing of his friend (and banker) Louis Le Prévost, Adrien set up a photography studio in the heart of Paris at 11 boulevard des Capucines. Convinced of his own abilities and the viability of the studio, Adrien told Nadar that he could run the studio on his own.

Nevertheless, given his interest in caricature, and his drive to capture the personality of his subjects, portrait photography held many appeals for Nadar. He learned the collodion process from his friend Camille d'Arnaud, an artist and former newspaper editor, who had recently begun making portrait photographs. Nadar quickly mastered the process and began to photograph his family and friends in the garden of his mother's apartment.

In 1854, the year that Nadar took up photography as a profession, he was married in a small ceremony to Ernestine Lefèvre. The same year saw the long-awaited arrival of his large illustration titled Pantheon, which, despite wide acclaim, was quickly embroiled in scandal. A sitter claimed that Nadar had included his caricature without the necessary written authorization with the result that sales of the Pantheon was prohibited in October 1854. Having given up on the Pantheon project altogether, Nadar accepted an invitation from his brother to help with his now failing photography studio. After several months the studio was functioning normally and Adrien again asked his brother to step aside in January of 1855.

Nadar, who had contributed to the purchase a new camera, and arranged for his well-known friends to attend the studio for sittings - and had even managed to secure a spot for the studio at the Exposition Universalle - felt that his interventions had rescued the studio. His efforts created confusion in the public's perception of the studio and as to who was running it. Adrien had also begun signing his photographs "Nadar jeune" (Nadar the younger). Nadar insisted that Adrien repay the money and cease using his name, but his brother flatly refused. Not only that, Adrien moved into a larger studio called "Tournachon Nadar and Company" with the assistance of two financial backers. An aggrieved Nadar subsequently moved his base of operations to his first floor apartment on rue Saint-Lazare. He continued portrait sittings for his friends and acquaintances, including Baudelaire and other modernists. Soon after, in February 1856, Nadar and Ernestine had a son, Paul Nadar.

Nadar was pushed to new levels of activity during these years, adding photographic portraiture to his role as writer and caricaturist. In order to prove himself as a legitimate photographer, Nadar joined the Société Française de Photographie, presenting his portraits in their annual exhibitions in 1856, 1857 and 1859. He also took steps to have his photographs discussed in the press and to have his name inserted in conversations about the status of the medium as a modern art form.

In December 1857, Nadar (with the backing of the French judiciary) gained exclusive rights to the name Nadar; winning a suit against his younger brother and being officially declared "the only, the true Nadar." Adrien tried to appeal the decision, but to no avail, and with the loss of the name he was quickly bankrupted. Despite their problems, and their fight over the Nadar name, the elder brother purchased the contents of Adrien's studio, including the cameras and equipment that he had helped to acquire just a few years earlier. Nadar was now determined to make photographic portraiture his chief means of income and duly purchased the grand building at 35 Boulevard des Capucines that had been vacated by the pioneering photographer, Gustave Le Gray. Nadar was in fact warned off the venture as the building commanded astronomical rent and had been left in a state of disrepair. Undeterred, and already in significant debt, Nadar refurbished the studio which opened in September 1861. Though a creative triumph, the studio never succeeded as a commercial venture and Nadar remained in debt.

Late Period

From the late 1850s, Nadar photographed prominent artists, actors, writers, and politicians in his lavish new studio, conspicuously located on one of Paris's busiest thoroughfares. Nadar photographed a veritable who's-who of Parisian society: Eugène Delacroix, George Sand, Gustave Courbet, Charles Baudelaire, Victor Hugo, Edouard Manet, Sarah Bernhardt, Emile Zola, and Jules Verne, among others. Not only did he photograph the burgeoning Parisian set, he sold photographs of his famous sitters to the public at large. Anyone who could afford to have their portrait made might also be able to purchase a small photo postcard (a carte-de-visite) of an artist or writer they admired. It was the birth of celebrity culture, a new phenomenon made possible by the reproducible medium of photography, and Nadar was quick to capitalize.

By the end of the 1850s the appeal of portraiture was no longer enough to satisfy Nadar's creativity. This realization, coupled with the death in 1862 of his longtime friend and mentor Charles Philipon, effected his decision to give up his connection to satirical newspapers altogether. During this later period, his interest in photography dovetailed with an interest in human flight and experimentations with new technological and scientific advancements.

As part of his mission to liberate the camera from the studio, and enthused with the possibilities for electric light, Nadar undertook photographic expeditions into the Paris catacombs. Nadar had spotted a commercial opportunity (by selling photographic reproductions) to capitalize on the Parisians' macabre fascination with the ossuaries hidden in the vast underground network. He used his improvised electric lamps to illuminate the city's dark vaporous caverns, producing a portfolio that was unprecedented for its time (Nadar's catacomb photographs were accompanied by a written piece in the 1867 Paris-Guide, published in conjunction with the Exposition Universelle).

In addition to his interest in subterranean Paris, Nadar explored the potential for shooting from above ground. Indeed, he grew increasingly interested in human flight and the photographic possibilities of shooting from a hot air balloon. Nadar was so convinced by the benefits of airborne photography - believing that it could be used for such purposes as mapmaking, surveying, and surveillance - he took out a patent for aerial photography in 1858. However, the necessity of preparing glass photographic plates in a moving balloon proved almost impossible, particularly when the gases escaped the balloon and altered the chemical composition of his silver baths. Nevertheless, Nadar overcame some of those challenges when he created the first aerial photographs of Paris in 1858; an event later immortalized by his friend Honoré Daumier in a lithograph entitled Nadar Elevating Photography to an Art (c. 1862).

Nadar's interest in "aerial navigation by heavier than air machines" ultimately led him to begin construction in 1863 on the world's largest hot air balloon, Le Géant (The Giant). It stood almost 200 feet high with a wicker gondola the size of a small cottage. A traveling studio of sorts, it was furnished with a darkroom, a seating area, a lavatory, and even a billiard table. Accompanied by a military band and enormous crowds, the balloon was launched to great fanfare. The maiden flight of Le Géant was not the grand voyage across Europe it promised to be. Technical difficulties had forced its landing just 25 miles outside of Paris. Subsequent voyages were similarly plagued with unforeseen problems, culminating, finally, in a crash in which the vessel was destroyed.

Le Géant a financial and technical failure, quickly swallowing up whatever profits the photography studio brought in. However, his work on Le Géant spurred him to establish a newspaper called L'Aéronaute in preparation for his first flight, and Nadar later wrote two books on his experiences with flying machines, Mémoires du Géant (1864) and Le Droit au vol (1865). While it was not the financial boon he was hoping for, the publications did succeed in opening the public's eyes to the possibilities for air travel.

In the early 1870s, his studio had become a meeting place for many disillusioned artists and writers frustrated with the current political and cultural establishment. Among the paintings included in the exhibition was Claude Monet's Boulevard des Capucines, Paris (1873), which was painted from the window on the second floor of Nadar's studio. That same year, Nadar retired to a house in the forest of Sénart, leaving his son Paul to run the photography studio. A year later, the Impressionists held their first public exhibition on the second floor of Nadar's studio on the bustling Boulevard des Capucines on April 15, 1874. In his final years Nadar wrote countless essays, books, and articles recounting his experiences and his friendships with many of the important personalities of the day. These writings culminated in his 1900 autobiography Quand j'étais photographe (When I was a Photographer). He died in 1910 at the age of 89.

The Legacy of Nadar

Nadar was a flamboyant figure who pursued an expansive set of interests (not all of them successful). He left his mark on nineteenth century Paris as (often at once) a journalist, caricaturist, photographer, writer and left-wing polemicist, scientist and even aeronaut. A romantic at heart - his early heroes included Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, and Eugène Delacroix - Nadar acquired an impressive roster of friends and clients - including Gérard de Nerval, Théophile Gautier, and Charles Baudelaire - most of who helped define his own legacy. His entrepreneurial spirit was evident in nearly every aspect of his professional life but his photographic portraits of the prominent artists, writers and intellectuals of nineteenth-century Paris proved to be era defining.

Indeed, Nadar proved a master at cultivating celebrity - for himself and for others - and it could be credibly argued that his industrialized approach to photographic portraiture, not to mention his drawn caricatures, gave birth to the phenomenon of modern celebrity culture. Yet in spite of his business savvy, Nadar was interested, above all, in using portraiture to reveal the inner character of his sitters. Based on mutual trust, and Nadar's infectious enthusiasm, he succeeded in creating a psychological connection with his subjects that was without precedent in the medium of photography at that time. As he later said, "What can [not] be learned [...] is the moral intelligence of your subject; it's the swift tact that puts you in communion with the model, makes you size him up, grasp his habits and ideas in accordance with his character, and allows you to render, not an indifferent plastic reproduction that could be made by the lowliest laboratory worker, commonplace and accidental, but the resemblance that is most familiar and most favorable, the intimate resemblance."

Influences and Connections

-

![Honoré Daumier]() Honoré Daumier

Honoré Daumier - Camille d'Arnaud

- Charles Philipon

-

![Charles Baudelaire]() Charles Baudelaire

Charles Baudelaire ![Victor Hugo]() Victor Hugo

Victor Hugo- Constantin Guys

- Paul Nadar

- Portrait Photography

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI