Summary of Ben Nicholson

One single work by Ben Nicholson can, at best, encompass architectural, sculptural, and painterly qualities, all the while retaining a powerful overarching worldview fueled by innocence, romance, and simplicity. Nicholson's career was long and impressive and can be divided into many phases. Even though early works appear naïve and childlike, he always experimented with pioneering theoretical and formal ways of making a picture. He initially favored still life and landscape compositions painted in a poetic and naturalistic style. From the early 1930s onwards however, his work began to develop in a more modernist direction, and he embraced working under the influence of late Cubism and abstraction. Winifred Nicholson, Alfred Wallis, Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian, and Barbara Hepworth all in turn had profound impact on the vision and style of Ben Nicholson. Throughout his career, there is an undiminished sense of a humble task at hand: that of honoring the beauty of landscape and life lived within it using a harmonious combination of color, line, and shape.

Accomplishments

- Nicholson is set apart from many of the fellow English painters of his generation because of his continuing interest in and understanding of Cubist painting. No other English painter exploited the technical aspects of Braque and Picasso's work to the extent that Nicholson did. Although always interested in Cubism (recording the moment of acute influence felt in 1921 when he saw his first Picasso), it was during the early 1930s - having spent time in the studios of Picasso, Braque, Hans Arp, and Constantin Brâncuşi - that the interest became Nicholson's commitment and main focus.

- Despite starting his career during a time of war and social struggle, unlike some artists working prior to World War I, Nicholson did not focus on politics. His main focus was art and he reintroduced the shunned genres of still life and landscape painting back into the limelight. Even the artist's early work points towards the fact that the history of English painting in the twenties is a history of the further development of the technical autonomy of a painting. Indeed, Nicholson's tastes were always closer to those of Roger Fry and the Bloomsbury Group than they were to Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism, calling quite simply for an "innocent" response to form and color.

- Furthermore, unlike his friend and colleague, Paul Nash, who always retained a relatively traditional perspective and vanishing point when painting a landscape, Nicholson was more concerned with shape and surface. Indeed, he produced a sense of depth through his original use of analogy, tone, and color. As such, his style is more aligned to the work of Paul Cézanne and to other pioneers in France, therefore successfully setting the basis for abstract art in England during the 1930s.

- Alongside Barbara Hepworth, Nicholson formed the nucleus of the St Ives School, a name that mistakenly makes a very international cohort of artists sound local. Incorporating also the work of exiles Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner, and inspired by the likes of Joan Miró, Alexander Calder, and Arp, the group based their principles on the notion of freedom, freedom of letting art be made in any form (as a mobile or relief, not only a traditional sculpture) and also a freedom from political and social oppression.

The Life of Ben Nicholson

Ben Nicholson’s legacy endures - even in his work as a schoolboy. So much so that family friend J.M Barrie based a poster for his famous play Peter Pan on a childhood drawing produced by the Nicholson (who was only 10 years old at the time the poster was printed).

Important Art by Ben Nicholson

1924 (Goblet and Two Pears)

Ben Nicholson's earliest paintings resemble his painter father's Vermeer-like portraits and sparse still-lives. In this painting, completed in the early years of his first marriage to Winifred Roberts, newly demonstrates the influence both of his artist wife (especially her free and abundant love of color and tendency to work more loosely and freely with paint) as well as the international art influences the couple had encountered on their extensive honeymoon in Europe, including most notably, paintings by Cezanne and Rousseau. The painting demonstrates Nicholson's early experimentation with new styles that would mark out his career.

It is important to remember that at this time Nicholson was also painting entirely abstract works, powerful, highly colored, grid-like formations dissecting the exciting language of Cubism. Interestingly though, he destroyed most experiments in this style including Trout and First Abstract (both made in 1924) and this painting, Goblet and Two Pears is more representative of his production at the time.

This was the moment that Nicholson re-invigorated the Seven and Five Group, and generally made paintings that had much in common both stylistically and in subject matter with his wife, Winifred Nicholson, and with his friend, Kit Wood. Together, they painted still lifes, landscapes, and portraits of friends. Above all, they attempted to achieve "freshness" of tone and color and to show "sincerity" in their approach to ideologically uncomplicated subjects. The Nicholsons along with Christopher Wood, together discovered the inspirational "primitive" work of retired fisherman, Alfred Wallis. The trio all expressed a preference for fresh light tones, and also showed enthusiasm for the Italian Primitives (especially Giotto). This particular still life is also interestingly comparable to the beautiful and meditative mid- to late-career still lifes by Giorgio Morandi.

Oil and pencil on board - Kettle's Yard, Cambridge, UK

1930 (Birch Craig, Summer)

This landscape was painted during the period when Ben and Winifred Nicholson were spending a lot of time in Cumberland, a rural area in the north of England. Here, they worked together with their friend Christopher (Kit) Wood, a painter who, like Nicholson, was influenced by the "primitive" style of untaught artists. The three artists worked in close collaboration between 1928-30 and there is considerable similarity in both style and subject of the artists' work at the time. Two years prior to painting this scene, together with Wood and Winifred, Nicholson had discovered the untutored master seascapes of retired fisherman, Alfred Wallis. All were profoundly impressed by the playful scale and wobbly perspective signature of Wallis. Childlike in vision, the influence of Henri Rousseau once again comes into play. Whilst Wyndham Lewis shunned this moment in creative history as the "cult of the child", Nicholson was fascinated and was indeed a personal friend of J.M. Barrie (creator of Peter Pan).

This idea of a "primitive" worldview is very evident in Birch Craig (Summer), as well as in its partner painting Birch Craig (Winter). The scene looks like a toy farmyard, made up of small things found in a child's playroom. The work also stands out as a focal piece displaying Nicholson's keen interest in a lyrical and poetic style, as well as his enduring love of landscape. Art historian Chris Stephens argues that this work is deeply rooted in the landscape it takes as its subject; he suggests its "pictorial unity" was "achieved through a process of intense looking": "an acute feeling for the particular quality and natural cycle of Cumberland light and dark, the often rapid changes in atmosphere and weather, is displayed." Nicholson captures the changing seasons in this series of paintings and thus reveals his own philosophical interest in the ongoing passage of time.

Oil on canvas - Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, UK

1933 (Saint Remy - Self-Portrait with Barbara Hepworth)

Saint Remy - Self-Portrait with Barbara Hepworth (1933) is a transitional work for Nicholson, straggling the realms of figuration and abstraction. It is a key example from a series of works that use simple lines and a monochrome palette; they are significant because they demonstrate an important shift away from his earlier descriptive landscape paintings towards his monochrome, abstract cut-out works of the mid-1930s. These heavily-line based works clearly show the influence of Picasso (Nicholson also did some guitar pictures in this style), here particularly in the swirling pupil of the eye of the foregrounded (female) figure.

The work is an intimate portrait of Nicholson with the sculptor Barbara Hepworth (whom he would later marry), presenting the two faces in profile, in union, overlapping one another. Despite the monochrome palette, Nicholson takes pains to delineate the shadow of the figure in the foreground, suggesting a specific light source. Through these tropes of form and color, the artist recalls the sculptural reliefs of classical friezes. The work sits at a junction between a classicizing tendency amongst modernist art, and a push towards abstraction. This is also suggested by the linearity of the composition, which evokes sculptural techniques of incision and carving, no doubt directly inspired by Barbara Hepworth.

At this time, in 1933, Nicholson was a fully-fledged member of the new British movement, Unit One. This group defined their interests as a combination of the love of design and the pursuit of form, as well as a thorough exploration of the psyche. All of the artists involved in the movement - Nicholson, Edward Wadsworth, Barbara Hepworth, Paul Nash, and Henry Moore - shared interests in the figurative, biomorphic, and the transition to abstraction. Work at this time continued to depict lots of bodies, but similar to Joan Miro and Pablo Picasso's paintings of the 1920s, extreme departures from literal anatomical accuracy were often made. Moore, in particular, defined the aims of the Unit One Group as creating reconciliation between the abstract and the human.

The art critic John Russell wrote of Nicholson's early 1930s linear works, "These paintings are the purest Nicholson: the fastidious fine-drawn line, the paint so transparent that the support seems to breathe through it, the delineation of objects which looks casual and elliptic but is really very much to the point. They give the feeling of life being lived on many levels, and of a world in which the image and the word are equal."

Oil on canvas - National Portrait Gallery, London

1934 (Relief)

After many years of experimentation across a wide variety of styles that incorporated post-Cubism and Surrealism, in the early 1930s Nicholson came to rest for a time on abstraction, and particularly on the medium of abstract geometric sculptural reliefs. The technique and process first came about by accident (interesting parallel to the chance work by Hans Arp) when a chip fell out of one of his prepared pieces of gesso ground and then he started to carve in relief. His first reliefs had a very inherent hand-made quality but soon after he began to paint his reliefs an overall even white. This important example shows the influence of Mondrian, and well as of his lover, the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, who was in the process of exploring sculptural responses to mass and spatiality. Nicholson had first met Mondrian the year before in Paris. There is rapid transition in his work of 1933 towards a form of abstract painting plainly influenced by developments in Paris in the later twenties. He was greatly inspired by the work of Miro, Arp, and Calder at this time.

Here, Nicholson eschews the colorfulness of his earlier paintings, as well as the neutral earthy tones of his first relief works, in favor of pure white. As curator and art historian Jeremy Lewison argues, the choice of the color white was significant: "White was the color adopted by modernist architects (such as Le Corbusier) to unify the structures of their steel and concrete buildings. It was also the color identified by Kandinsky as signifying potential and was to some degree a metaphor for the cleaner, brighter, fairer society that those involved with geometric abstraction and modernist design and building aspired to achieve in the 1930s. [...] Finally, in their insistence on whiteness, Nicolson's reliefs mirrored Hepworth's translucent alabaster and white marble sculptures of the same period." Talks of the aims of Unit One at this time stated that Nicholson was interested in "an idea, which is complete, with no beginning and no end and therefore giving to all things for all time". The result is a very modernist piece of art indeed, a work that is at once like a painting, a sculpture, and even a dwelling place.

Oil paint on mahogany - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

November 11 1947 (Mousehole)

This painting demonstrates the literal coming-together of various different facets of Nicholson's working styles and influences. After the outbreak of World War II, demand for European-inspired abstract artworks significantly declined, making life financially difficult for Nicholson and Hepworth. They moved to Cornwall, where Nicholson began to paint Cornish landscape scenes at the advice of his dealer, echoing a wider cultural trend towards British nostalgia and the elevation of British values. As Nicholson specialist Virginia Button notes, Nicholson "was ambivalent about this return to nature in his work, describing his landscapes as ‘Cornish best-selling schemes'. But the Penwith Peninsula nonetheless had an immediate effect on the development of his work."

November 11 1947 (Mousehole) shows the combination of influences at play during this period. On the one hand, it represents an idyllic Cornish countryside scene depicting the harbor of a small fishing village, whilst on the other hand, Nicholson clearly holds on tight to his love of Cubism. The representation of the fishing boat, in particular, demonstrates the influence of Alfred Wallis. On the other hand, the scene also includes an abstracted collection of geometric shapes, pointing to an ongoing interest in continental artistic endeavor. These shapes suggest more an abstract view of still life rather than a landscape and as such echo the earlier more lyrical and painterly phase of Nicholson's career. Indeed, this collapsing of indoor and outdoor space, in which still life objects appear to be superimposed on a landscape, became a key trope of the artist's painting in the subsequent year.

Oil and pencil on canvas mounted on wood - The British Council, London

1951 (Festival of Britain mural)

In 1951, the Festival of Britain was created to celebrate British art, design, and architecture, and to kick-start creative industry in the aftermath of WWII. A number of buildings were commissioned - including the Riverside Restaurant in Surrey, near London - as well as various paintings and sculptures.

The commissioners of the Riverside Restaurant wanted to include a concave mural to mirror the impressive curved elements in the building's architecture and Nicholson was commissioned. For the final mural, the central panel is flat, while the outer two pieces are curved to form an embracing triptych-like structure. The wholly geometric composition demonstrates Nicholson's return to abstraction, which was from thus forth to become his dominant mode of artistic expression. It also expresses the conclusion to the many experiments in abstraction that he had continued to make throughout the war on a small scale; whilst such works had been constrained by the scarcity of materials and income, this mural gave platform to showcase his ideas unbounded. The painting also very interestingly, painted almost 30 years on, uses the exact same color palette as Goblet and Pears (1924).

Tate curator Terry Riggs argues that Nicholson's design also captures some of the key architectural concerns of the day: "The use of dynamic lines also paralleled such architectural forms in the Festival as the Skylon designed by Powell & Moya. Reflecting the fashion for openly displaying support structures, fretwork girders were no longer clad but were prominent on the outside of buildings, setting up rhythmic patterns. Nicholson's mural echoes these concerns."

Oil and pencil on three curved panels - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

August 1956 (Val d'Orcia)

The mid-1950s provided Nicholson with an opportunity to travel again, after the restrictions of WWII. Moreover, an increase in the availability of materials and in Nicholson's income allowed him to create more ambitious works. Paintings from this period also mark the height of his influence on the St Ives School, which had emerged and then grown rapidly in Cornwall around himself and Barbara Hepworth, with the pair actively encouraging abstraction and new approaches to making art.

In August 1956 (Val d'Orcia), Nicholson re-visits his interest in combining landscape scenes and still life objects. In this painting, the distinctions between foreground and background, between object and landscape have been elided and erased, suggesting an attempt to break down the boundaries imposed by painterly categories, and to explore and confront the definition of what makes a "picture".

Art historian Jeremy Lewison claims that this work, along with others produced in 1956 represented for Nicholson "the apogee of his career as a painter of still life, combining sensitivity to tone and texture with a dynamic, rhythmic line. Their ostensible subjects were the bottles, goblets, carafes and mugs that had fascinated him throughout his life, [...] but they can be interpreted as metaphors for societal structures: architectural agglomerations of the spires, steeples and church towers of England, the campaniles and churches of Italy, as well as the complexity of human relations and social intercourse."

Oil paint, gesso and graphite on board - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Feb 1960 (ice-off blue)

Towards the end of his career, Nicholson returned to the concept of the relief, which had characterized some of his most successful works during the 1930s. While he had previously made use of a cool, monochrome palette consistent with the aims of modernism when making more sculptural works, in the 1960s he began to experiment more with color, particularly with neutral tones and blues (reminiscent of the earth and the ocean). Furthermore, while his early pieces had involved cutting out geometric shapes, in Feb 1960 (ice-off blue) he utilizes carving and scraping directly into the thick board, as well as treating other areas with heavy shading and saturated pigmentation.

The curatorial team at Kettle's Yard, Cambridge, argue that in this painting and in another similar composition, that "by using a variation of lighter and darker tones, Nicholson tricks your eyes into thinking that the darker areas are deeper than they really are. There is also a touch of white along the incised lines, making it seem as though the rectangles are floating in front of each other, or as if something is glowing behind them."

By using meticulous techniques of carving and painting, Nicholson echoes the vagaries of real light on a landscape. This work draws together both the cool modernism of his early abstract work with the observation of light, place, and objecthood captured in his mid-career as well as later landscapes and still lifes. Ultimately, like many of his works, here too is a painterly, poetic, and abstract landscape, which paradoxically imitates nature whilst also standing as a considered departure from it.

Oil paint on board - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

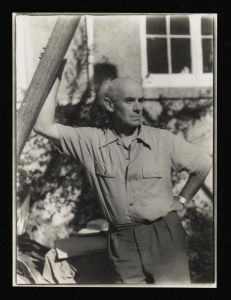

Biography of Ben Nicholson

Childhood

Ben Nicholson was born on April 10, 1894, in Denham, Buckinghamshire, to a family with art at its heart. His father, Sir William Nicholson, was an eminent portraitist and still life painter, while his mother Mabel also came from a family of artists and studied at art school. He had three siblings: Anthony, Nancy (an artist) and Christopher (an architect).

The Nicholson family, who moved to London in 1896, were connected to various artistic and intellectual circles, and were acquainted with figures such as Rudyard Kipling, Walter Sickert, and William Orpen. The family often traveled in Nicholson's early years, and in 1904 the young artist met the playwright J.M. Barrie while on holiday with his parents. During the same year, Nicholson's father had painted Barrie's portrait, and as all became better acquainted, Barrie decided to base a poster for his famous play Peter Pan on a drawing done by the young Ben Nicholson. From the ages of 9-16, Nicholson was educated at a boarding school in Norfolk.

Early Training and Work

In 1910, at the age of 16, Nicholson enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art. Although he left after only one year, he had managed to form friendships with some very influential contemporaries, including Paul Nash, Stanley Spencer, and Christopher Nevinson. He also came into contact with artist and critic Roger Fry, whose ideas would become fundamental in changing the British art landscape. Nicholson's own work, however, remained relatively conservative for a number of years and he never became directly affiliated with The Bloomsbury Group.

In the years leading up to World War I, Nicholson travelled to France, Italy and Portugal, studying languages. During this time, it has been noted by art historians such as Sebastiano Barassi that the young Nicholson attempted to use his art to compete with his father, with whom he sometimes had a difficult relationship. As he suffered from asthma, Nicholson was exempted from military service during the war. In 1917, he was sent to New York in order to have his tonsils removed. When he returned to Britain the following year he was sadly confronted with the deaths of both his beloved mother and eldest brother Anthony, the former died in an influenza epidemic, and the latter fighting in action.

This was a deeply difficult period for Nicholson. Not only did he just lose both his mother and brother, but also swiftly after, his father married Edie Stuart-Wortley, a woman to whom Ben Nicholson himself had been engaged to the previous year. Nicholson's troubles began to manifest themselves in his art, and he momentarily turned to current artistic movements for inspiration and ways to express himself, such as Fauvism and Vorticism.

During 1920, Nicholson met the young artist Winifred Roberts and soon afterwards visited Cornwall with her and her family. By November the same year, the pair were married. On their honeymoon, they visited Italy, and wrote to their friends that they were unimpressed by much of the Renaissance art they saw: "It is astonishing how few really 1st class A1 painters there have been," Nicholson wrote to a friend, "And people like Tintoretto, Fra Angelico & Michelangelo have vastly... overrated reputations." Nevertheless, they do both seem to have been heavily influenced by the icy pastel tones of some Renaissance frescos.

After their honeymoon, Winifred and Nicholson bought a house in Switzerland, where the couple each had a studio. They remained living in Lugano during the winters of 1920 to 1924 in an attempt to aid Nicholson's bad health. Despite living abroad they continued to spend their summers in England, often stopping off to see contemporary shows in Paris on the way. They had good contacts with a number of Italian artists based around Milan, and particularly with those associated with the Novecento Italiano group. This broad influence base helped both artists to experiment with new forms and ideas, and also to move away from the artistic traditions of both of their families. The couple had three children together.

Nicholson had his first solo exhibition in London in 1922, and in 1924, he joined the Seven and Five Society. The group was initially relatively conservative, but it was ready for change and by the time Nicholson took the helm, the outlook was more radical and pointed towards abstraction.

When in the UK, Winifred and Nicholson lived at "Bankshead", their house near Brampton in Cumberland. The couple met the young artist, Christopher (Kit) Wood who was also profoundly influenced by time spent at Bankshead, writing that "the Bankshead life is the painter's life". In August 1928, whilst spending time in Cornwall, the trio of artists together discovered the work of retired fisherman Alfred Wallis; they were all greatly influenced by the raw and untutored manner of his painting. By this point, Ben and Winifred Nicholson and Christopher Wood had become the typical and leading representatives of the "Seven & Five style".

Mature Period

At some point during the late 1920s, Ben and Winifred moved back to London. They were surrounded by a group of artists keen to establish a new movement. In 1931, Nicholson met Barbara Hepworth. Nicholson joined her on a holiday in Norfolk, along with Hepworth's then-husband John Skeaping, as well as Henry and Irina Moore, and Ivon Hitchens. Ben and Winifred separated the same year. This trip sowed the seed for the flower that grew to be the group called Unit One. Its members included Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Paul Nash, Ben Nicholson, John Armstrong, John Bigge, Edward Burra, Frances Hodgkins, Edward Wadsworth, Wells Coates, and Colin Lucas.

Beyond London, Nicholson was also at the centre of European art scenes at this time, frequently travelling to Paris, where he met figures such as Mondrian and Picasso, both of who became important influences on his work. He also began to regularly visit St Ives, a small fishing village in Cornwall, England, which later became an epicentre of artistic activity and home to the St Ives School. His activities and work at the time were central to the promotion of abstract art in England.

Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth showed their work together in joint exhibitions in 1932 and 1933, demonstrating a combined and concerted movement towards abstraction. Hepworth later said of their relationship: "As painter and sculptor each was the other's best critic". In 1932, Nicholson moved in to Hepworth's north London home, where they shared a studio, and in 1934 Hepworth gave birth to triplets. The pair continued to collaborate, notably on the publication Circle, which was edited by Nicholson and designed by Hepworth. This was the time when more sculptural aspects came into Nicholson's work; influenced by Hepworth he importantly started to develop his abstract relief pieces.

In 1938, Ben and Winifred Nicholson were finally and officially divorced, although having been separated for a long time, and Ben married Barbara Hepworth in November of the same year. In 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II, Hepworth and Nicholson moved from London to St Ives in Cornwall where they lived in relatively harmony for some time, becoming part of the local community and continuing to make art prolifically.

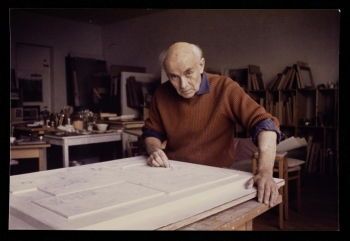

Late Period

In 1951, Nicholson left Hepworth and split his time between Cornwall and London, where he began to receive greater critical recognition. It is not known why Nicholson left his wife, but the suggestion is that 20 years of juggling family life and art had taken a toll, and also that Hepworth's new desires to make large-scale sculptures with social intent deviated from the more purely artistic ideals that the couple shared. In 1952, he received the Carnegie Prize, and in 1956 he was awarded the first Guggenheim International painting prize. In the previous year, 1955 a retrospective of his work was presented by the Tate Gallery; thanks to this as well as wide international exposure in British Council tours during the 1940s and 1950s, Nicholson by this point was considered a worldwide success.

In 1957, Nicholson met the German photographer Felicitas Vogler, who had travelled to St Ives to make a radio programme. The pair married only a few weeks later, and in 1958 they moved to Castagnola in Switzerland, where they built a house with a beautiful view of the Swiss landscape. Nicholson encouraged Vogler to take her photography seriously and she started to take pictures professionally. In 1968, Nicholson received the British Order of Merit, recognising his contribution to British art.

In 1971, Nicholson and Vogler separated and Nicholson moved to Cambridge in England, followed by Hampstead in London, near to where he had previously lived with Barbara Hepworth. Vogler and Nicholson were finally divorced in 1977, and Nicholson died in 1982 at the age of 87.

The Legacy of Ben Nicholson

Nicholson was crucial and central to the formation of two movements in his lifetime, as well as being responsible for the transformation of another. This was a great feat for a British artist, as historically they have struggled to form groups and drive movements, often preferring to work alone and in isolation. Nicholson, by contrast, alongside colleagues utterly revolutionized the goals and direction of The Seven and Five Society. Later, in 1933 some of the members of Seven and Five created Unit One recognizing the need to push the strong and flowing current of modernism further. Although Unit One only remained active for two years they were prolific and exhibited widely during this time, often being credited for establishing the pre-eminence of London as a centre for modernist painting, sculpture, and architecture during the mid-1930s.

Nicholson's influence on the future and legacy of St Ives in Cornwall, making it the second major artistic hub in the UK after London cannot be in any way underestimated. St Ives became the unquestionable center for modern and abstract developments in UK art from the 1940s to the 1960s, and this was thanks to Nicholson and a few close fellow artists. Alongside Hepworth, Nicholson shifted the direction of St Ives from a quiet seaside town to the dynamic centre for the arts that it remains today. He likely acted as the catalyst for the introduction of the Tate Gallery to this location, and furthermore established the small town as at once a haven and a hotbed for artists of many generations to follow. Nicholson's legacy is also interestingly and inextricably entwined with those of Winifred Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Kit Wood, and Alfred Wallis. These artists all discovered, shaped, and influenced the careers of one another, and in turn the development of British art.

Influences and Connections

-

![Barbara Hepworth]() Barbara Hepworth

Barbara Hepworth -

![Alfred Wallis]() Alfred Wallis

Alfred Wallis -

![Christopher Wood]() Christopher Wood

Christopher Wood - William Nicholson

- Winifred Nicholson

-

![Vorticism]() Vorticism

Vorticism -

![Fauvism]() Fauvism

Fauvism -

![Cubism]() Cubism

Cubism -

![Primitivism in Art]() Primitivism in Art

Primitivism in Art ![Folk Art]() Folk Art

Folk Art

- Peter Lanyon

- Patrick Heron

- Terry Frost

- John Wells

- John Piper

-

![Barbara Hepworth]() Barbara Hepworth

Barbara Hepworth -

![Paul Nash]() Paul Nash

Paul Nash - Winifred Nicholson

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI