Summary of Amédée Ozenfant

Ozenfant is best known as the co-founder, with the Swiss Le Corbusier, of Purism, a movement that called for a return to order in painting during the tumultuous years that followed the Great War. Reacting against Cubism, which he dismissed as a "decorative art of romantic ornament", Ozenfant conceived of a modern style of painting that promoted clarity, harmony, and precision. But for many, Ozenfant exerted his greatest influence as a writer and educator. Indeed, Ozenfant came to be regarded as one of modernism's most erudite and provocative commentators. He was a formative influence on the architect Le Corbusier and with him co-authored the book-length Purist manifesto, Après le Cubisme (After Cubism), and co-founded the influential cross-disciplinary arts review, L'Esprit Nouveau (A New Spirit). Ozenfant carried great influence into the classroom, too, establishing his successful "Ozenfant Academies" in Paris, London, and New York.

Accomplishments

- Although Ozenfant was hostile towards what he saw as the ornamental distractions of the avant-garde, Purism was itself categorically modern. His still life (the genre of choice for the Purists) images featured simple groupings of mass-produced objects placed against a plain background. His paintings were executed with geometric clarity, mathematical accuracy, and smooth unbroken brushwork, that closely resembled architectural blueprints of building details. Like his colleague, Fernand Léger, Ozenfant initiated a more simplified take on Cubism that many have cited as the forerunner to Pop Art.

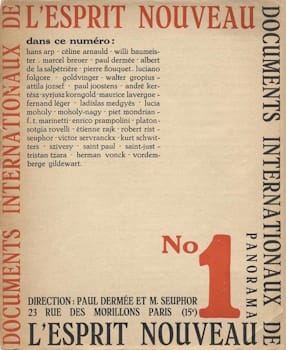

- One of Ozenfant's greatest contributions to the landscape of interwar modernism came through his primary role as co-founder/editor/contributor to the arts review L'Esprit Nouveau. Running for 28 editions over five years (1920-25) it embraced almost all areas of the creative arts. It published articles by some of the greatest thinkers of the age with its influence spreading throughout Europe. As historian H. Allen Brooks put it, L'Esprit Nouveau "brilliantly captured the spirit of this intellectually exciting age".

- Having already made his mark as a theoretician to be reckoned with the publication of Après le Cubisme (1918), and the arts reviews, L'Élan and L'Esprit Nouveau, Ozenfant confirmed his pedagogic credentials through a long list of publications, including his hugely influential book, Art (1928) (translated as Foundations of Modern Art (1931). His reflections on the interrelationship between all forms of human creativity, including science and religion, saw it become one of the most widely read books by any modern artist.

- Ozenfant was keenly invested in the idea of the machine age. However, the Purist view of the machine differed fundamentally from that of Futurists who revered machines of destruction for their "cleansing" qualities. For Ozenfant, the machine age allied with a utopian view of mass production that would help facilitate the reconstruction of postwar France. In this respect, Ozenfant and Le Corbusier's search for universal elements across art and architecture allied with the general "call to order" promoted through the Interwar Classicism movement that was sweeping through the artworld in the post war years.

The Life of Amédée Ozenfant

Arts writer Suzanne Muchnic argues that with Purism, Ozenfant had invented a "rigorous, precise, pure art attuned to the science and industry that permeated modern life".

Important Art by Amédée Ozenfant

Bouquet de Fleurs (Flower Bouquet)

In this, one of Ozenfant's earliest works, painted when he was just twenty-three and near the beginning of his studies at the Académie de La Palette in Paris, we are presented with a fairly ordinary flower arrangement, executed in a Post-Impressionist style that reflected the tastes of his teacher, Charles Cottet. The color palette is rather muted, with grey, off-white, muddied teal, and pale pinks, however Ozenfant also included some small bursts of colored flowers, in bright orange and deep red.

Indeed, it was during his time at the Académie de La Palette that Ozenfant started to develop his strong interest in color. Although color would become suborniate to form in his works of the 1920s, it would later return as the most significant element of his painting, and a topic upon which he theorized and wrote a great deal in later decades.

Oil on canvas - Private collection

Nature Morte au Verre de Vin Rouge (Still Life with Glass of Red Wine)

After years of studying and reproducing the styles of his tutors, and after witnessing Cubism emerge as the dominant avant-garde movement, Ozenfant, with Swiss architect Le Corbusier, proffered a new artistic movement which they called Purism. Ozenfant began to paint simplified objects represented in non-abstracted ways, from a singular point of view, and using flat planes of color in rejection of Cubism's preference for muted "brown" tones. In this still life (the preferred genre of the Purists) we are presented with a guitar, a pitcher, a wine bottle, drinking glasses, and other vessels, painted mostly in neutral colors, with a few areas of deep red and green. In their co-authored 1920 essay "Purism", Ozenfant and Le Corbusier declared, "Of all recent schools of painting, only Cubism foresaw the advantages of choosing selected objects, and of their inevitable associations. But, by a paradoxical error, instead of sifting out the general laws of these objects, Cubism only showed their accidental aspects, to such an extent that on the basis of this erroneous idea it even re-created arbitrary and fantastic forms".

Ozenfant chose to depict wine bottles in many paintings as they were a way of representing the machine-age that, to his eyes, had become an intrinsic part of modern life. In fact the design of the wine bottle, which had remained essentially unchanged throughout history, perfectly symbolized a world of mass produced utilities/receptacles. Historian Luke Younger adds, "Ozenfant respects the nature of these items, and illustrates the objects so that they are easily recognizable and do not create erroneous forms like the Cubists. The viewer is now able to make associations with previous personal encounters or experiences. It was through these simplifications and modifications to the Cubist school that Ozenfant developed a new way of painting, a technique in which the viewer is able to participate in the nature of happiness upon viewing and making associations with the work".

Oil on canvas - Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland

Accords

This canvas, created when Ozenfant and Le Corbusier were still in the early stages of developing their theories on Purism, presents a still life, featuring overlapping objects, including a guitar, cups, a vase, a wine bottle, and a pitcher, against a black background. Each form is represented by a nearly monochromatic area of pale colors, with only some of the objects featuring shading (such as the rounded edge of the pitcher). The background at the upper right includes faint, blurred, grid-like geometric details, and the overall composition can be described as geometrically or mathematically ordered, symmetrical, and harmonious.

In the early days of Purism, Ozenfant and Le Corbusier prioritized form over color, writing in their 1918 book, Après le Cubisme, that "The form is preeminent, colour is but one of its accessories. Colour depends entirely on the material shape [...] Colour is coordinated with form, but the reciprocal is not true. We believe, thus, that a theme should be selected for its forms and not for its colours". Moreover, the Purists' focus on geometrical harmony and symmetry exemplifies their goal of rejecting (or rather revising) Cubism by returning to simplicity and emphasizing logic and rationality.

In works such as Accords, the involvement of mathematical modes of thinking is made evident, such as in the carefully designed proportions of the objects, and the inclusion of forms that represent mathematical functions, such as the grid. Writing in their 1920 essay "Purism" the two men proposed that "With regard to man, esthetic sensations are not all of the same degree of intensity or quality; we might say that there is a hierarchy. The highest level of this hierarchy seems to us to be that special state of a mathematical sort to which we are raised, for example, by the clear perception of a great general law (the state of mathematical lyricism, one might say); it is superior to the brute pleasure of the senses; the senses are involved, however, because every being in this state is as if in a state of beatitude".

Oil on canvas - Honolulu Museum of Art, Hawaii

Nature Morte a la Bouteille (Still Life with Bottles)

At first glance this painting appears to be one more still life featuring bottles and glasses, this time painted predominantly in blue, grey, black, and white. However, as arts writer Suzanne Muchnic notes, the work exemplifies Purist ideals by merging "traditional still-life objects with architectural forms and references to modern industry. The overlapping cluster of bottles and drinking glasses can be read as architectural columns and smoke-stacks". Art historian Kenneth E. Silver adds, "We find, in fact, the ideal image, a blueprint for the 'social contract' of a perfectly functioning, post war French society. Here Frenchmen are to see themselves in the things of their own manufacture, identifying themselves with natural and mechanical selection".

The Purist iconography of factory-made objects saw them aligned with the Futurists' fetishization of the machine. Art historian Jamie Morra states, "Amidst the new concerns of the postwar era, artists searched for new ways to represent the conditions of a transformed society. Purism was born of a new spirit that sought pristine order amid the chaos that had ensued and aimed at doing so through math, science, and mechanization. [...] The Purists believed that France would be redeemed by industry, and the technological tools of war would instead become the tools of peace and progress". This turn to machines as a source of inspiration likely came more from Ozenfant than from Le Corbusier, with Ozenfant writing later in life that "we took out lessons from the fine things of industrial technology [...] especially from my familiarity with speed machines".

Ozenfant and Le Corbusier themselves wrote (in their 1920 essay "Purism"), "Mechanical selection began with the earliest times and from these times provided objects whose general laws have endured; only the means of making them changed, the laws endured [...] In all ages, for example, man has created containers: vases, glasses, bottles, plates, which were built to suit the needs of maximum strength, maximum economy of materials, maximum economy of effort". They concluded that "the respect for the laws of physics and of economy in every age created highly selected objects; that these objects contain analogous mathematical curves with deep resonances; that these artificial objects obey the same laws as the products of natural selection and that, consequently, there reigns a total harmony, bringing together the only two things that interest the human being: himself and what he makes".

Oil on canvas - Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California

Composition aux Personnages

This painting is dominated by flat, overlapping, geometric fields of color (primarily yellows, blues, and browns, with one small orange rectangle near the top right corner), as well as sporadic simple lines (both straight and curved). 1930 marked the point at which Ozenfant began to introduce the human form into his works and we see here two faces seen in profile. At the same time, he turned his focus away from a total focus on form with a new emphasis on color. Over the remainder of his career Ozenfant would in fact be marked by a near obsessive exploration of the function of color in painting, announced through a series of articles renouncing his earlier views on the matter.

As Communication and Design professor Carolyn Kane notes, earlier Purist works could be characterized as "chromophobic", that is, works marked by "the restricted use of colour to muted tones or primaries, or the subservience of colour to primacy of line and form", because color belonged in the end "to the realm of disorder". However, forward of 1930, Ozenfant began to understand that color possessed the ability to "enhance architectural form" by way of juxtaposed contrasts. This shift in Ozenfant's thinking was due in large part to his relationship with Neo-Impressionist painter Paul Signac, who had himself been influenced by the theory of "optical blending", put forth by nineteenth-century French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul.

With works such as this, Ozenfant began to favor saturated hues, paying particular attention to the sensory and psychological effects of color. This latter consideration may likely account for the simultaneous introduction of human forms into his work, perhaps symbolizing his newfound concern with the interplay of color in art and the human psyche. He even reportedly urged his students at his London Academy to treat color "as if there were a natural relationship between the actual fragility of pigments and their effect on our intuitive psychology".

Oil on canvas - Private collection

Voilier (Yacht)

In Voilier, the sailboat of the title is represented on the left-hand side by two simple, clearly defined, stark white brushstrokes (a horizontal stroke for the boat and a curving, pointed vertical one for the sail, with shading indicated by an adjacent medium-blue form), and its reflection in the water which is rendered through whisper-like strokes below. The background is a solid field of serene blue, with nothing to demarcate the horizontal separation between sea and sky. Floating above the upper-right half of the painting are several small forms, in a variety of bold colors, that appear like floating papers or pieces of fabric - perhaps bunting - though Ozenfant's true intention with these forms is unknown.

This simplistic formula for representing sailboats was also used in his 1959 work 3 Voiliers (3 Yachts), and his 1963 work 36 Voiles (36 Sails), among others, and all of which feature a solid blue background. Indeed, toward the end of his life (this piece painted three years before his passing) Ozenfant's works became more meditative, while retaining the simplicity and balance of his Purist leanings. One can imagine that the elderly Ozenfant, nearing the age of eighty, and recently moved to the seaside town of Cannes, had found a poignant beauty in seascapes, and used his own renditions as a way of reflection upon his life.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Biography of Amédée Ozenfant

Youth and Early Training

Amédée Ozenfant, the second of three children (a brother and a sister) was born in Saint-Quentin, a city in the Aisne department, Hauts-de-France, (the Northern most region of France) to devout Catholic parents. His father, Julien Ozenfant, ran a successful public works office, while his mother, Marie Thérèse Ozenfant, had an interest in drawing and enamel paintings (she sold her work locally). His siblings enjoyed good health, being very active in sports, whereas Amédée was a sickly child. Curator Pierre Guénégan writes, "Too often absent from school, he got only average grades and was pampered by his grandparents who also lived in the family home. His father, [an] entrepreneur and tireless worker, was an example for this boy of fragile health. [...] Ozenfant had few conversations with his strict father preoccupied by work [although he] admired and respected his father for who he was and what he undertook".

Ozenfant suffered from bouts of bronchitis, pleurisies, and pneumonia and was sent to the warmer climes of Arcachon in Southern France where he continued his schooling at the Dominican school of Saint Elme. Ozenfant later recalled "after so many years spent heart to heart with my sweet grandmother, no parting was ever so painful". However, he found that he enjoyed life as a boarder, and while the school was run by priests, it had a relatively liberal approach to teaching which included a strong focus on art. He recalled, the Friars "tried to mold us into well-behaved, cultivated people with aristocratic leanings ... I certainly had no cause to complain in such a magnificent place: becoming a painter for good was unavoidable". Indeed, it was at Saint Elme that he learned pastel and watercolor techniques and took out subscriptions to arts journals and reviews through which he acquired an early love of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

Ozenfant returned to Saint-Quentin in 1904 where he enrolled at the Quentin la Tour Municipal School of Drawing. He attended a drawing workshop with French genre painter Jules-Alexandre Patrouillard Degrave, and studied the decorative arts under Maurice Pillard Verneuil, a French art critic and artist working in the Art Nouveau style. Ozenfant's works from these early periods were mostly still lifes and landscapes which he rendered in his favored pastels and watercolors.

Ozenfant's parents encouraged his study, financing trips abroad to visit art museums, before agreeing to his request to move to Paris on the proviso that he study painting and architecture. In 1907 he enrolled at the Académie de la Palette where he formed a close friendship with the Cubist Roger de la Fresnaye, and the Impressionist André Dunoyer de Segonzac. Ozenfant soon became bored with studying architecture, however, and devoted all his energies to painting (with his parents' blessing). He studied under French painters and engravers Charles Cottet and Jacques-Émile Blanche although the naturalistic style of these teachers would have no noticeable influence on the work for which he was to become known. Indeed, Ozenfant's work was becoming more abstract, and his focus turned more toward the use of color over line or form. He favored the vivid colors preferred by the likes of the Neo-Impressionists, while his strong interest in technology, mechanics, and cars attracted him to the work of the Futurists. While at the Académie, Ozenfant also developed an interest in Asian, Egyptian, and African art. In 1908 and 1910 Ozenfant exhibited his first works at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, and the Salon d'Automne, respectively.

During this period, the Ozenfant family business was enjoying great financial success and this trickled down to their son who was able to finance the life of a young dandy, dressing in fine clothes and frequenting cafes, salons, concerts, and operas. Ozenfant became friends with Auguste Rodin and the Russian, Sonia Terk (future wife of Robert Delaunay). Through Terk, he met Zina Klingberg, who he married in Moscow in 1909 (his brother and father travelling to attend the ceremony). Ozenfant spent long spells in Russia between 1909 and 1913 and here painted a series of gouaches called Le voyage en Russie. During his "Russian period", Ozenfant and his brother designed a car frame for a Hispano Suiza engine, creating a prototype called the "Hispano-Ozenfant" in 1911.

Ozenfant left Moscow one last time in 1913. He toured Italy (visiting Venice, Florence, and Rome) and, in 1914, returned to Saint-Quentin following the sudden death (cause unknown) of his brother. In the same year he had a chance encounter with the Neo-Impressionist painter Paul Signac who invited Ozenfant to Sisteron in Provence. Ozenfant made many sketches of the village and surrounding countryside (and would return there at various points throughout his life). With the outbreak of war, Ozenfant returned to Paris.

Mature Period

Having avoided the draft (probably due to his poor health record) Ozenfant, a proud patriot, felt compelled to contribute to the war effort as best he could and struck on the idea of creating a review that promoted nationalist values. In 1915, Ozenfant co-founded the short-lived artistic review L'Élan with writer, painter, and critic Max Jacob, and poet, playwright, and critic Guillaume Apollinaire. The aim of the publication, which ran to just ten issues, was to maintain ties between the avant-garde artists in France and those who had been sent to the war front. The final issue of L'Élan was published in 1916 and included Ozenfant's essay "Notes on Cubism". He continued to research and write extensively on a range of topics, including typography, Cubo-Futurism, and "psychotypy" (the exploration of the rhythms of poetry).

For Ozenfant, L'Élan was a vital tool by which to present his thoughts on the relationship between art and war. He wrote, "The foreigner may think that art in France belongs only to peacetime. [But] those who are fighting, our friends, tell us how much the war has been to the advantage of their art, and they would like some place to show it. [...] This French journal is also the journal of our allies and our friends. [...] It will fight against the enemy wherever it finds it, even in France [...] our only goal being the propaganda of French art, of French independence, in sum, of the true French spirit". In the last issue of L'Élan Ozenfant employed the term "Purism" for the first time.

At this time, Ozenfant socialized with artists from various movements including Cubists such as Juan Gris, the sculptor and illustrator Henri Laurens, the architect Auguste Perret, and the Futurist Gino Severini. Ozenfant's artistic production underwent a transformation at the time, with his paintings mirroring L'Élan's typographic choices: space became fragmented into cuboid, abstract and figurative elements all at once. Such pictorial offerings were unparalleled in France, perhaps he may have also been influenced by Russian Suprematism. It was Perret, who he met with often and had long conversations about painting, who offered to introduce him to one of his former collaborators, a young Swiss architect called Charles-Édouard Jeanneret. Perret told Ozenfant: "he's a little odd, but you'll find him interesting".

In 1917, Ozenfant's father died suddenly. His mother was left to run the family business but, with no experience of managing a large company, she fell prey to corrupt advisors and was soon declared bankrupt. Ozenfant received a modest inheritance but he could no longer finance the lavish lifestyle to which he (and his wife) had become accustomed. In July 1918 he and Zina were divorced. Ozenfant withdrew into his art and started to formulate his new theory which he formally named, "Purism". Guénégan writes, "[Ozenfant] felt the need to start over and streamline his attention to reach what he called his purist dream. [...] Wanting a complete break with the past, he burned many drawings, studies, and projects, keeping only a sofa bed and a few chairs before moving to his next abode at rue Godot de Mauroy near the Place de la Madeleine in Paris".

Ozenfant first met Jeanneret in May 1917 (he adopted his better known pseudonym, Le Corbusier, in 1920 after it first appeared in an early edition of the review, L'Esprit Nouveau). The two men spent many weekends in Arcachon Bay on France's southwest coast where they formulated their ideas on Purism. Ozenfant also found a new partner at this time, Germaine Bongard, with whom he was in a relationship until 1923. Bongard ran a successful avant-garde fashion house and he and Bongard opened a boutique in Bordeaux called "Jove, couturier-decorator". Although Ozenfant had a "hands-on" involvement with the business, he continued to meet with Jeanneret regularly, working together on literary works and on an exhibition of their paintings and drawings.

By the end of 1918, the two artists were ready to present their ideas to the Parisian artworld. They published their manifesto, Après le Cubisme (After Cubism), in November and followed with their first exhibition in December. The exhibition launched at Bongard's dressmaking salon on Rue de Penthièvre (it was renamed "Galerie Thomas" especially for the occasion). The exhibition consisted of still lifes featuring mass-produced objects and utensils such as wine bottles, pipes, books, and everyday kitchen items. Although critics of the day expressed some reticence towards Purism's "dull" objectivity (the renowned critic Vauxelles, for instance, objected to the lack of human/romantic content in the work, writing: 'I wish one morning Ozenfant would say to Jeanneret: 'My friend what would you say to lunch on the grass at Meudon [a suburb of Paris] in the company of two beautiful girls?"), Ozenfant wrote in his memoirs that he felt "elated and cheerful [...] Our ideas were going to fly to Paris! [...] The war ended, an era died, the leader of the last manifestation of his art disappeared. Cubism entered into history alongside war".

Ozenfant, Le Corbusier, and the Belgian poet and critic, Paul Dermée, co-founded the review, L'Esprit Nouveau (A New Spirit), that first published in October 1920 (the name of the review was reportedly proposed to the men as "a challenge" by Guillaume Apollinaire). L'Esprit Nouveau was committed to connecting all fields of modern creative activity, including painting, sculpture, architecture, literature, music, engineering, theater, the music hall, cinema, circus, sports, costume, books, furniture, the aesthetics of modern life. Guénégan states that, "For the 1920 launch of the review they had a pamphlet printed detailing their goal: 'The style of an age can be seen in general production and not, as is too often believed, in a few decorative pieces, mere superfluities of a style-generating structure'. High performing industrial products corresponded to the new aesthetics, or rather to the new philosophy that they wanted above all else to protect". The review's launch was complemented by a second Purist exhibition at the Druet Gallery running between January 22 and February 5, 1921. The paintings of Ozenfant and Le Corbusier were so similar that several critics commented that it was hard to tell who had painted which painting.

Around this time, Ozenfant was introduced to a wealthy Swiss art collector named Raoul La Roche. Ozenfant agreed to help La Roche build his collection by acting as an art broker. It saw Ozenfant embroiled in one of the most infamous episodes in the history of early-20th-century modernism. Following the outbreak of war in 1914, the famous German art dealers Daniel Henry Kahnweiler and Wilhelm Uhde were obliged to leave Paris because of the hostilities. Both men had their vast modern art collections impounded by the French government. After the war, between 1921-23, four auctions were held at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris which saw hundreds of the seized works sold off, including key works by Braque, Picasso, Gris, Fernand Léger, André Derain, Henri Rousseau, and Auguste Herbin, at bargain prices.

Kahnweiler's erstwhile friend, Léonce Rosenberg, who nominated as the "expert" at the auctions and this infuriated Kahnweiler and his supporters. There are conflicting stories concerning Ozenfant's role in the auctions. One version tells how Braque had become so enraged at the treatment of Kahnweiler he physically attacked Rosenberg and had to be restrained by Ozenfant. The other version tells it that Braque punched Ozenfant in the face calling him a "treacherous bastard". What is beyond dispute is that Ozenfant purchased a large number of works by Braque, Picasso, and Gris, for the "give-away" price of 80,000 francs, on Laroche's behalf. The idea amongst the artists' fraternity that these pieces had been grossly devalued (and therefore their historical and aesthetic significance belittled) was only compounded when Ozenfant acquired several further works that he claimed were investments for the L'Esprit Nouveau. Ozenfant later said of his own purchases: "I suspected that one day, despite its success, the 'Esprit Nouveau' would have to pack up: at that time an art review could not survive long without subsidy. And so I bought a few pieces by Picasso and Braque for the Esprit Nouveau Company along with other pieces including the complete edition of 100 copies of an important unseen Picasso etching, for a few francs. My intention was to later distribute it amongst the shareholders as compensation".

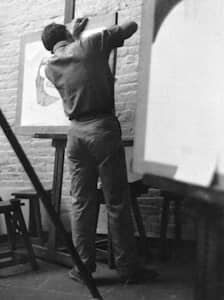

As L'Esprit Nouveau became more established, Le Corbusier gained growing renown as an architect. Despite the fact that the two men were slowly growing apart, Ozenfant persuaded Le Corbusier to build him a workshop ("for a limited price") and, in 1924, Ozenfant, with co-founder Léger, opened Académie Moderne, a free art school which attracted other instructors such as the Russian painter and designer Aleksandra Ekster, and French painter Marie Laurencin. Following the publication of its penultimate issue (no. 27), Ozenfant left Le Corbusier in sole editorial charge of L'Esprit Nouveau. Ozenfant did, however, exhibit with Léger at the Pavillon de L'Esprit Nouveau, a model home, constructed by Le Corbusier and his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, for the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris.

Around this time Ozenfant was suffering financial difficulty and he diversified his interests by opening a new fashion house - named simply "Amédée" - with his future wife, Marthe-Thérèse Marteau. Despite being mocked by some in his circle as "a dressmaker!", the couple's business was a commercial success. Ozenfant and Marteau were married in 1925 (and remained a couple until Ozenfant's passing, forty-one years later). By the end of 1925, the relationship between Ozenfant and Le Corbusier had become acrimonious: Guénégan states, "A genius can have no master and Le Corbusier showed complete ingratitude towards his old friend. Ozenfant certainly refused to be outdone and never missed an opportunity to point out to Le Corbusier that he was artistically beholden to him, which naturally did not go well".

In 1928 Ozenfant published a book titled Art (retitled as The Foundations of Modern Art when it was published in English in 1931), in which he reflected on the interrelationship between all forms of human creativity, including science and religion. Over time, the book would become one of the most widely referenced books written by a practicing artist. His musings were further expressed through his art, in which he created economical, reductive still lifes in which objects were represented in flat planes of neutral color and organized in harmonious compositions. However, Ozenfant was starting to distance from the early form-focused impetuses of Purism. He discovered a new interest in color and produced a good deal of research on the topic of color's role in art, especially in terms of how color affects human psychology and the spatial and architectural effects of color.

Ozenfant was financially buoyant with the "Amédée" doing well and with commissions made from his continued brokers role with La Roche. Ozenfant noted: "In 1929 [...] I bought myself one of the most admired cars of the time, a Bugatti race car ... after some difficult years I went back on the road, long drives to Antibes or Arcachon ... days spent in the fields, the mountains, by the seaside, what a beautiful life! LA BELLE VIE was the name of my new period in which many nudes composed arabesques of freedom!". Ozenfant entered into a new partnership with the art dealer Paul Guillaume (who also represented Modigliani). Guillaume took an interest in Ozenfant's Purist works but was not at all enthused about his "La Belle Vie" pieces. Meanwhile, Jeanne Castel opened a gallery on Avenue de Messine in 1930 which she inaugurated with an exhibition of Ozenfant's "La Belle Vie" pieces. The exhibition proved a disaster with not a single piece sold.

Over his career, Ozenfant had fostered many contacts in Germany, one of which was the architect Erich Mendelsohn who asked Ozenfant to decorate his newly built villa in Berlin. Ozenfant produced two murals that drew praise within Mendelson's influential circle of friends. His reputation in the ascendancy in Germany, Ozenfant gave lectures in Stuttgart, Berlin, and Dessau, where he met with Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. He travelled to Egypt, Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Greece. Ozenfant was especially fascinated by Athens and produced many photographs and sketches of the Parthenon that, on his return to Paris, he saw published in the journal Cahiers d'Art.

In 1932, Ozenfant established, the Académie Ozenfant, at his existing art studio. In 1934, he met the art critic Jean Cassou, and other foreign intellectuals to discuss the creation of a new multidisciplinary (such as music, photography, architecture, theater, printing, sculpture, ceramics) international art school. The project came to fruition at a location near Saint-Tropez in Southern France but ended suddenly following a devasting fire in 1935. Ozenfant was not to be discouraged and returned to teach at Académie Ozenfant before he took the decision to move to London where he established the Ozenfant Academy of Fine Art, in September 1936. Amongst his students were Surrealists Leonora Carrington and Stella Snead, and the multi-media artist Sari Dienes.

Late Period and Death

In July 1938 Ozenfant took up an offer from the University of Seattle to teach on one of its summer schools. He and his wife travelled by ship from Normandy to New York. On arrival in New York, Ozenfant recalled, "we walked directly from the French Line Pier towards the Rockefeller Center. The impact upon us was of the same kind as that we had felt before the pyramids ... the American Acropolis immediately became one of my greatest emotional experiences of architecture". From Seattle he visited the West Coast, the national parks region, and the Grand Canyon. In San Francisco he met, and formed a lasting friendship, with the American modernist painter, Stuart Davis (who were already known to each other through the American's vocal admiration with the work of Léger). Fully enamored with the United States, and increasingly aware of the troubles brewing in Europe, Ozenfant returned home in the spring of 1939 to wrap-up his interests in France and England. He sold his Paris workshop and moved out of his London residence before moving to New York where he set up his workshop-cum-academy, named the Ozenfant School of Fine Arts.

In 1941 the Chicago Arts Club gave Ozenfant his first retrospective exhibition. The exhibition brough him widespread renown in the US. His New York school became a huge success and he put on a number of exhibitions in the city. Ozenfant also found a way to contribute to the war effort over the airwaves. He recalled, "I was introduced to a certain Madame Helen Mann [and] she tells me almost immediately: Roosevelt is creating a radio station to communicate with the entire world through shortwave broadcast: 'We need collaborators, you can write and you have a good voice; so join us...'" He worked on a program called "Voice of America" (produced by the French journalist refugee Pierre Lazareff). The French section of the "Voice of America" was first broadcast from a studio on Madison Avenue before moving to 57th Street, near Carnegie Hall. [Many] artists in exile would participate in 'Voice of America': Chagall, Dalí, Ernst, Breton, [...] Léger, Mondrian, Lipchitz, Masson, Tanguy, Hélion and many others. These prominent figures would also contribute to establishing New York's reputation as an international capital of art". Indeed, several museums acquired Purist pieces and Ozenfant, Léger and Piet Mondrian formed a tight relationship, and were involved in individual and collective exhibitions. In 1944 Ozenfant became a naturalized American citizen.

Leading up his return to France in 1955, Ozenfant recalled "I was living in American [sic], English came to me almost instinctively. I dreamed in English and when I thought of returning to France, I believe I did so in English. I had never imagined I would one day consider this place [New York] home, which led to an emotional conflict because I very much liked the Americans, and it pained me to leave them. [...] I was no longer of an age to waste time: it was time to focus my efforts on painting and writing, to seek fulfillment. The biggest difficulty lay in my attachment to my students [...] my school was profitable and had become the most high-profile school in the United States".

Having been based in Paris for two years, Ozenfant settled finally in Cannes where he continued to paint and teach. However, during his time in America, Le Corbusier (who had remained in Europe) had gained international renown and had taken to publicly belittling Ozenfant. While Le Corbusier was enjoying high profile events (such as an exhibition in 1953 at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris) Ozenfant had been effectively ignored in his own country. It was only the Berri-Lardy gallery in Paris (directed by an American named Edwin Livengood) who promoted Ozenfant's paintings. The gallery put on two exhibitions that provided modest success. But Ozenfant remained in Le Corbusier's shadow and he was suffering renewed financial hardship.

Soon, however, Ozenfant was introduced to a Cannes/Paris dealer called Katia Granoff. He recalled, "Katia bought what she wanted from me and I submitted what I liked to her [...] She never tried to 'lead' me by imposing painting sizes or subjects etc. ... I would send her my paintings, she would thank me, attaching a check, I would thank her in return. We almost never spoke of money, but of painting and poetry ... Renoir used to say of his art dealer Durand Ruel that he was a missionary. 'We are lucky, us impressionists, that his religion happened to be painting'. The same could be said of Katia Granoff". During this late period, Ozenfant periodically returned to his Purist roots though he was mostly attracted to painting seascapes.

Ozenfant took on one final student in Cannes (a fifteen-year-old girl) upon the recommendation of François Bret, the director of the École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Marseille. His final writings were devoted to his memoirs, which he had begun in 1961. Ozenfant was decorated as "Officer de l'ordre des Arts et des Lettres" in 1962 and, in 1963, Laroche donated two paintings from Ozenfant's Purist period to the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris. Ozenfant died in Cannes in May 1966 at the age of eighty, after complications from a surgery. In his memoirs he reflected upon the origins of Purism: "Was the term Purism well chosen? Every word in existence strongly suggests some more or less precise idea. Purism said one of our intentions well: purity; but it didn't say much more than this".

The Legacy of Amédée Ozenfant

Through his writing, Ozenfant proposed that it was through "simplification, distortion of forms, and modifications of natural appearances" that the modern artist could arrive at the most "intense expressiveness of form". It was a credo adopted by the architect Le Corbusier, and in the working practices of the likes of Juan Gris and Fernand Léger. Through his role in the launch of L'Esprit Nouveau (A New Spirit), meanwhile, he was instrumental in one of the most successful reviews devoted to "the aesthetics of modern life". As New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) put it, L'Esprit Nouveau summarized "the energetic, boundary-crossing spirit of Paris between the two world wars". Similarly, Ozenfant's most important book, Art (AKA, Foundations of Modern Art), amounted to a perceptive study of the interrelationship between all the creative arts was becoming a fixture of art students' reading list to this day.

Beyond his Purist phase, Ozenfant's theories on color were strongly influential on much interwar art and decoration in Europe. As architecture critic William H. Braham notes, Ozenfant's theories on color were read with great interest by the students at the Architectural Association (AA), and especially for "David Medd, a student at the AA who later authored the color standards for British schools". Yet despite his achievements, Purism as a movement was relatively short-lived and its influence did not have much of a geographical reach. Eliel believes that "one of the reasons that this movement has not gotten the critical and academic and curatorial attention that it might have in the English-speaking world is that these writings weren't accessible in English. Many people were just not aware of their existence". Nevertheless, Purism can today be viewed as a precursor to Pop Art which also took as its subject matter mass produced consumer culture. As art historian Jamie Morra notes, the Purists "understood that capitalism and consumer culture had begun to shape irrevocably the ways in which bodies and minds interacted with one another and one's surroundings".

Influences and Connections

-

![Paul Signac]() Paul Signac

Paul Signac -

![Paul Cézanne]() Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne -

![Georges Seurat]() Georges Seurat

Georges Seurat -

![Pierre Puvis de Chavannes]() Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes - Charles Cottet

-

![Leonora Carrington]() Leonora Carrington

Leonora Carrington -

![Roy Lichtenstein]() Roy Lichtenstein

Roy Lichtenstein - Sari Dienes

- Stella Snead

- Madeleine Laliberté

Useful Resources on Amédée Ozenfant

- Foundations of Modern ArtOur Pick

- Journey Through Life: Experiences, Doubts, Certainties, Conclusions

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI