Summary of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

The works of the great 19th-century muralist Puvis de Chavannes, a pivotal figure poised at the threshold of modernism, still adorn public buildings in Paris. Their classically-inspired allegorical themes invoke a timeless, pre-industrial past, adhering to the rules of painting established in the Renaissance. However their shallow, collapsed spaces and broad swathes of color do not adhere to these rules, thwarting proportion and perspective. His own style incorporates bits and pieces of the new and the old, and achieves the transcendent effect that was his goal. Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso (the list reads like a "Who's Who" of modernism) recognized him as a visionary, and he in turn admired the new generation of anti-academics. In his public commissions he focused on themes that pleased the French government (family, order, loyalty, etc.), but he also supported and mentored avant-garde artists, and his work evolved in tandem with theirs. Puvis was one of few academics of any time period who was able to see change coming and adapt to it - the mark of a truly great mind.

Accomplishments

- His murals are the ancestors of today's public art. Dependent upon context for meaning, his works were meant for site-specific city spaces. Their allegorical subjects related to the specific goals and aims of libraries, schools, and other civic spaces. They were meant to address a broad audience that went beyond the public that visited museums and galleries. Audiences deeply appreciated this dimension of the work as part of the architectural space and institutional life of the city.

- The tranquility of Puvis's scenes might lead us to believe this was a quiet period in history. In fact, he constructed his dream-like pictorial fantasies in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune (1871-1872). During the war, Paris citizens survived on a diet of rats and water and under the Commune (an attempted coup that resulted in a blood bath), civic spaces were destroyed and the city hall burned. As such Puvis was part of a city-wide effort to repair the morale of the nation. The escapist dimension of his work is all the more poignant when we realize the 20th century would be even worse. This is also part of the legacy of abstraction. As Paul Klee (another Puvis admirer) put it, "the more horrifying this world becomes, the more art becomes abstract."

- Like many great artists, Puvis doesn't fit neatly into one movement. His career overlapped with Impressionists, Post-Impressionism, and Symbolism. He engaged, mentored and learned from artists involved in each of these movements.

Important Art by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

The Pastoral Life of Saint Geneviève

Puvis's murals for the capital depicting the life of the patron saint of Paris were created over a five-year period. The work is bordered with leafy garlands that lend a decorative quality. Even more emphatically, near the ceiling of the Pantheon a riot of decorative elements, a great frieze of twenty-two haloed figures and a winged monster, hang above the mural. While one sees more shading here than in some of Puvis's later works (which grew flatter and flatter) the abundance of vertical elements (figures stand like columns) that seem to hold up the wall, unlike the diagonals that lead the eye into fictive space (i.e. one-point perspective) in the manner of Renaissance painting. This excited a generation of avant-garde artists, among them Picasso, who set about copying the whole mural immediately after arriving in Paris in 1900. One sees reverberations of it in the elongated figures of Picasso's blue period.

These scenes were commissioned three years after the destruction caused by the Franco-Prussian War and the French Commune, a devastating period from 1870-71. Installed in the Pantheon, a former church turned civic building, these murals were an instant critical success that led to future commissions. Classicism (which had fallen out of favor after Napoleon) had re-entered the vocabulary of politics. Puvis's statuesque, draped figures celebrate the return of Classicism and the story of the founding of Paris. A symbol of new beginnings in the present as well as the past, a young Geneviève stands in the center panel of this triptych. Saint-Germain d'Auxerre, having arrived in Nanterre with Saint Loup de Troyes, notices she is bearing the divine seal. The fanciful decorative elements and clarity of form in this geometrically balanced work, coupled with its idealized references to the past, made it an instant success with officials and the public. Puvis's later works would build on this classicizing imagery, radically reducing and simplifying it, and expanding its associations to embrace universal symbolism.

Oil on Canvas - Pantheon, Paris

The Poor Fisherman

Under a grey sky, a fisherman stands at the prow of his boat, arms folded, as if in prayer. Behind him are a naked child and a mother gathering the sparse dandelions that grow on the shore. Whether the child will be fed or has already starved is unclear. One of Puvis's best-known works, this canvas displays a private mood rarely shown to us in his wall-sized paintings, and may offer us a glimpse of his personal psychology. It was developed over the course of several years through sketches and painted studies, and executed during a personally challenging time for the artist.

With the success of his first murals in Paris in 1878, Puvis was anxious over his future prospects and the amount of artistic freedom he would exercise. When showing this work at the Salon of 1881, Puvis indicated that he wanted the painting to be regarded in "human, natural terms," with no religious, mystical, or philosophical symbolism. Paintings of fishing had Christian overtones in European art, and Puvis's own oeuvre included such pictures (Miraculous Draught of Fishes and The Fisherman). Puvis's insistence that there was no such symbolism here allowed him to introduce an element of realism to the work, without losing the attention of an audience accustomed to viewing religious subjects. Puvis had reservations about showing this work at the Salon of 1881, since it departed considerably in both subject matter and style from earlier triumphs, and he turned out to be correct. Conservative critics slammed it, taking issue with the lack of traditional proportion and shading. However it won him the respect of a new group of admirers, including Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who championed the work, making reference to it in later writing, with the former incorporating Puvis's painting into his Landscape with Puvis de Chavannes' Poor Fisherman, circa 1881. Maurice Denis, a founding member of the Nabis, specifically admired the work and in his publication "Definition of Neo-Traditionalism," Denis called for a new type of painting his writings. Interestingly, sculptor, printmaker, and sculptor-painter Aristide Maillol executed a direct copy of this work.

Oil on Canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

The Dream

Presented at the Salon des Artistes Francais of 1883, The Dream depicts a sleeping man - most likely a traveler, given the bag at his side. Three airborne women approach, one with roses suggesting Love, one with a laurel wreath denoting Glory, and a third distributing coins representing Fortune. Broad planes of muted color are interrupted by stylized details such as the branches that spring from the earth. Unlike his mural cycles, made for public consumption, it is a private, non-literary, self-contained image that describes a dream.

Like the two-faced Roman god Janus, Puvis's work looks backwards and forwards at the same time. The Dream typifies this tendency. In privileging symbolism and fantasy over naturalism and reality, it recalls Romantic painting. In giving free reign to the imagination, it anticipates the wilder fantasies of the next generation. Compare this, for example, to the Sleeping Gypsy by the eccentric, self-taught Henri Rousseau, which might be seen as a reprise of this composition in reverse. Puvis actively championed and supported the next generation of younger and more radical artists who shared his desire to escape the realities of modern, industrialized society through dreams, esoteric symbolism, or mythology. They in turn were inspired by him. Puvis's effect on younger artists seeking an alternative to Realism, on the one hand, and the academy, on the other, went far beyond his efforts as a muralist.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Le Bois Sacre

In 1886, Puvis received a watershed commission from the Sorbonne's architect Henri Paul Nénot. Nénot requested a hemicycle mural in the university's main amphitheater celebrating the secularization of schools in Paris, and depicting the breadth of disciplines in the modern curriculum. Nénot wanted a single outdoor composition recalling Raphael's School of Athens, with the humanistic disciplines on the opposing side of the theoretical and applied sciences.

The central figure, a secular Madonna, the "Virgin of Science" refers to the laicization of the educational system. Two figures on either side of her lend a grounded, human aspect to the composition amidst references to abstract concepts. History appears as a figure landing upon archaeological ruins, emphasizing the importance of material evidence and analysis in a contemporary approach to studying the past. Here Puvis used mural painting as a means of communicating ideals in a highly visible, central location that hosted public speeches and performances.

In August 1889, the French President Sadi Carnot inaugurated the amphitheater in the company of dignitaries and various emissaries from universities abroad. The mural was unveiled two days later, an occasion during which Puvis received the high honor of Commandeur de la Legion d'Honneur. Famously, student demonstrators attempted to destroy these murals in the major French riots of 1968, viewing them as a symbol of unyielding tradition in the contemporary French establishment.

Oil on Canvas - University of Paris IV - Sorbonne, Paris

Summer

During the Paris Commune in 1871, the town hall (Hôtel de Ville) was burned down and the Third Republic was established. This mural, commissioned for the new town hall, functions as a seasonal allegory and a political statement. The work is marked by lush hues and a signature flatness - though the gradual size reduction of the background figures roughly follows the laws of perspective and dimension. What results is a distorted hierarchy of figures and a dream-like composition of a different era. Georges Seurat, Pablo Picasso, Paul Gauguin, and their contemporaries responded and integrated flatness and unnatural, simplified figures into their practices. What lacks in this sensual portrayal of summer, however, is a distinct narrative and objective among the idealized bathers.

The presence of summer and water in the decorative scheme for the new town hall resonated with the citizens of Paris as a symbolic antidote for the bitter winter of 1870 under the Franco-Prussian war, and the real flames that had consumed the old town hall in 1871. Even in 1891, both events were still fresh in people's minds. In Puvis's choice to depict fantasy over recent segments in history, the intended audience is transported back to a classical, more peaceful time.

Oil on Canvas - Hotel de Ville, Paris

Murals at Boston Public Library

By the late 1890s, thanks to an exhibition of Puvis's work in New York, the artist had begun to develop a robust following among American artists and collectors. In 1895, the Boston Public Library hired him to help them decorate the grand staircase and second-floor gallery of the majestic new building designed by Charles Follen McKim. As in his other large-scale public commissions, Puvis designed an allegorical scheme appropriate to the institution. The central panel, The Muses of Inspiration Hail the Spirit of Light, depicts the nine muses of Greek mythology in a grove of laurels and olives, receiving the Genius of Enlightenment. The title is an adaptation of Puvis's own written explanation of the piece, "The muses of inspiration hail the spirit, the harbinger of light". In another panel - Philosophy, Plato speaks with a disciple in an Athenian landscape, indicated by the Parthenon in the background. Poetry consists of three panels: Virgil visiting his beehives; Aeschylus and Prometheus, sitting on a cliff by the sea and chained to a rock, respectively; and a blind Homer receiving laurels from two female figures representing The Iliad and The Odyssey. The composition's mathematical divisions compliment the architecture. Puvis, who had never set foot in the library, worked closely with marble samples and architectural models in his studio in France to complete the eight stairway murals. These murals serve as a reminder that wisdom can be acquired only through study and introspection, a principle and work ethic that Puvis maintained throughout his life.

Oil on Canvas - Boston Public Library, Boston

Biography of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

Childhood

Pierre-Cécile Puvis, later known as Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes, was the youngest of four children born to Marie-Julie-César Puvis and Marguerite Guyot. His father found success as a chief mining engineer and encouraged his son to follow in his footsteps. Puvis lost both parents as a teenager - his mother in 1840 and his father in 1843. In 1841, he attended the Lycée Henri IV in Paris and prepared for admissions to the École Polytechnique. However, he decided not to sit for the exams, much against his father's wishes. At a later date, Puvis once again did not take the entrance exams - this time due to illness - and discontinued attending classes at the Faculty of Law. To regain his health, he spent two years in Macon with his sister Josephine and her husband.

Early Training

Puvis's formal artistic training was sporadic, if not short in duration. In the late 1840s, he spent half a year under the tutelage of Henri Scheffler and in 1848 made a lengthy trip to Italy, where he was exposed to the works of Giotto and Piero della Francesca. Upon returning to Paris, he commenced studies with Eugène Delacroix, who was soon forced to shut down his studio due to illness. Before taking a course in anatomy and perspective at the École des Beaux-Arts, Puvis studied for a few months under the painter Thomas Couture, whose style featured hard contours and shading. In the decade following 1849, he continued his education via contact with fellow artists and teaching himself rather than formal training. Alongside several friends, who included artists working in painting and engraving, he worked off the model of an ensemble which he called The "Academy" (not to be confused with the officially-sanctioned royal institution also known as the Academy, in Paris, from which he felt somewhat removed) that offered camaraderie and support to one another through artistic feedback.

Mature Period

Around the age of thirty, Puvis met Princess Marie Cantacuzene. She was his main confidant in artistic matters and later became his wife. Marie often sat for his paintings, appearing notably in his portrayal of a young Saint-Geneviève. He also formed a strong friendship with the Impressionist painter Edgar Degas at the beginning of both their artistic careers.

Between 1854 and 1855, Puvis ambitiously set out to execute a mural cycle. At the time, all wall space at the Hôtel de Ville had been promised to other prominent artists (Delacroix, Jean-Auguste-Dominiques Ingres, and Henri Lehmann). Since no public commission was immediately available, he embarked on a series of decorative paintings for the chateau Le Brouchy, his brother's country estate. This kicked off his career as a decorative painter.

Puvis struggled initially to receive institutional support and recognition. This feeling of instability would persist, even after a series of successes. He submitted Jean Cavalier at the Bedside of His Dying Mother to the Salon in 1852, along with other pictures, but failed to gain acceptance until 1859, with an enlarged version of his mural The Return from the Hunt. This greatly affected his view of official art institutions and gave him an unusual degree of empathy for the struggles of young, unrecognized artists for the remainder of his career. It was not until this period that mural paintings gained the prestige that had previously been awarded to other types of painting.

In 1859, the same year that his first work was accepted to the Royal Academy, Puvis appended the noble designation "de Chavanes"to his family name (changed to "de Chavannes" in 1877) and began a love affair with his model Suzanne Valadon (born Marie-Clementine Valadon and also known as Maria Valadon), an artist, and mistress to several high-profile painters in Montmartre. By the early 1860s he was exhibiting and selling work at the Salon on a regular basis. His induction into the Legion of Honor at the Universal Exposition of 1867, secured his position as an institutional insider.

Late Period

Puvis's critical fortunes rose steadily in the last two decades of his life. At a time when critical agreement was rare, both liberal and conservative critics hailed the frescos he unveiled at the Sorbonne in 1889 as a crowning achievement of the decade. Puvis was promoted to Commander of the Legion of Honor, and the society he had helped to found with Ernest Meissonier and Auguste Rodin (Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts) held its first salon in 1890. A one-man exhibition in New York in 1894 helped cultivate an American audience that remained robust until the mid-20th century. In 1897, Puvis married Princess Marie Cantacuzene, his partner for over four decades. They both died the following year after prolonged illnesses, two months apart. According to the artist's wishes, his heirs presented many of his drawings to French museums.

The Legacy of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

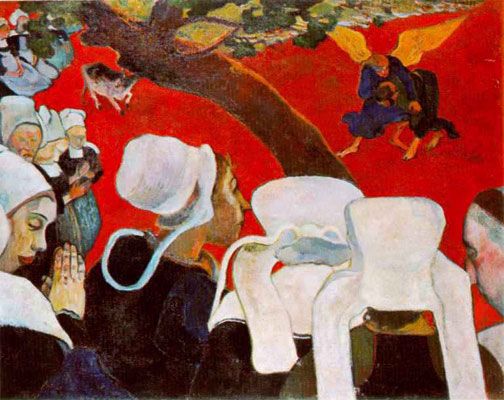

Puvis's impact on the history of art would be difficult to overstate. His aspiration to escape reality and turn inward - toward dreams, mythology, and the imagination - inspired the Post-Impressionists. The comingling of the real and supernatural in Gauguin's Vision After the Sermon, the psychic interiority of Seurat's Les Poseuses, and Cézanne's search for structure all have analogies in the work of Puvis. Another group of artists obsessed with Puvis were the Nabis, whose founder Maurice Denis paraphrased Puvis in his modernist credo: "Remember that a painting, before it is a war horse, a nude woman or some anecdote or other, is essentially a flat surface, covered in colors arranged in a certain order." Puvis's connection with the French literature of the 1880s anticipated the aesthetics and ideals of Symbolism. His languid, classical forms were copied by Picasso shortly after his arrival in Paris, lending form and substance to the Spaniard's famous blue period.

What Picasso and others saw in Puvis is still visible now: a shift away from representation and toward the language of formal abstraction. Born a generation before Van Gogh, Seurat and Toulouse-Lautrec, Puvis outlived them all and surveyed the past and future of art more calmly than these younger artists who took more risks in life and art. Nevertheless, his flat expanses of muted color and simplification of form were radical in their implications, and of great interest to 19th-century Western theorists, and his focus on painting's physical qualities - paint as paint - informed the most famous art theorist and critic of the 20th century, Clement Greenberg, as late as the 1960s.

Influences and Connections

![Thomas Couture]() Thomas Couture

Thomas Couture

Useful Resources on Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

- Pierre Puvis de ChavannesOur PickBy Aimee Brown Price

- Dream States: Puvis de Chavannes, Modernism, and the Fantasy of FranceBy Jennifer L Shaw

- From Puvis de Chavannes to Matisse and Picasso: Toward Modern ArtBy Serge Lemoine

- Berthe Morisot, the Correspondence with Her Family and Friends: Manet, Puvis de Chavannes, Degas, Monet, Renoir and MallarméBy Berthe Morisot

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI