Summary of Jacob Riis

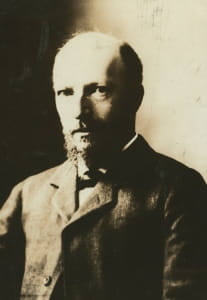

Riis was one of America's first photojournalists. As a newspaper reporter, photographer, and social reformer, he rattled the conscience of Americans with his descriptions - pictorial and written - of New York's slum conditions. As an early pioneer of flashlamp photography, he was able to capture the squalid lives of immigrant families living on the very edges of society. His lectures and, subsequent books, including the famous How the Other Half Lives (1890), was so influential that they brought about new legislation to improve tenement housing conditions and general standards of sanitation across America. Riis's work is hailed now as the precursor to so-called "muckraking journalism" that became a fixture in American newspaper publications after 1900. His most glowing endorsement came from (the future US President) Theodore Roosevelt who referred to him as "the best American I ever knew [sic]" with "the great gift of making others see what he saw and feel what he felt".

Accomplishments

- With books such as, How the Other Half Lives (1890) and The Children of the Slums (1892), Riis created great public interest, and garnered widespread acclaim, that fueled several urban social reform programs. As a result, history sees him as both a forerunner for American Documentary Photography and Social Documentary Photography. When coupled with his statewide tours, where his lectures were accompanied by lanternslide displays of his photographs, Riis created a visual and written record that created a popular audience for the art form that was to become known as Photojournalism.

- After reading about the invention of magnesium flash powder, Riis was amongst the first to recognize the possibility of night photography. He began visiting the slums at night, where, accompanied by two assistants and a policeman, he sometimes startled the residents with the abrupt flash of his camera. Some have criticized Riis's methods as intrusive but his drive to capture the most honest, "unsuspecting", moments with his camera was driven by a mission to bring about reform in tenement housing and thus, for him, justifying his methods.

- Although Riis was a pioneer of (the ostensibly neutral) Documentary Photography, he allowed for an element of symbolism to enter his work through the motif of the seemingly mundane object of the clothesline. Initially viewed by him as a nuisance (that distracted from the picture he was trying to capture) he came to recognize it as symbolic of people who were struggling to live honest lives. Riis wrote: "The true line to be drawn between pauperism and honest poverty is the clothes−line. With it begins the effort to be clean that is the first and the best evidence of a desire to be honest".

- As Riis matured as a photographer, he learned to build a rapport with his subjects. This led to a series of portrait photographs, usually of slum children forced into manual labor. His images, of which he wrote, "the young are naturally neither vicious nor hardened, simply weak and undeveloped, except by the bad influences of the street, makes this duty all the more urgent as well as hopeful", were included in the book, The Children of the Poor (1892). The book proved so influential it moved the church and, even individual families, to take abandoned children into their direct care.

- In his latter images, Riis turned his attentions away from the human figure onto rows of tenement housing. For Riis, these houses, many constructed by unscrupulous builders, contributed to the early death of their occupants. Through his 1892 book, The Battle with the Slum, Riis highlighted the issue of poor sewage and water sanitation, that contributed to diseases such as typhoid. His maxim was: "It is squalid houses that makes squalid people".

The Life of Jacob Riis

Acknowledging the power of the photograph to swing public opinion, Riis wrote: "My writings did not make much of an impression - these things rarely do, put into mere words - but my negatives, still dripping from the dark-room, came to reinforce them".

Important Art by Jacob Riis

Bandits' Roost, 59 1/2 Mulberry Street

Eighteen of Riis's photographs first appeared in a photo essay called "How the Other Half Lives" in Scribner Magazine's 1889 Christmas edition, one of which was Bandits' Roost. The iconic image shows a gang of Italian toughs, all sporting bowler caps, in a notoriously dangerous alley called The Bend, a neighborhood between Mulberry, Baxter, Bayard, and Park Streets in New York City. Riis said of The Bend, "Abuse is the normal condition...murder its everyday crop". Two men on the right seem to guard the entrance, as the shillala (club) that one man holds heightens the sense of menace. Behind them, another man casually perches on a staircase railing (perhaps he is in command of the gang) while three other figures cluster on the staircase on the other side, all of them turned toward Riis's camera. Meanwhile, a woman and a child lean out of windows in the building on the right, while in background, clothing hangs on lines strung along the alley. A sense of crowded poverty and desperate circumstances becomes the backdrop for Riis's emphasis on the criminal element (as echoed in his title). The lines of the buildings seem to almost converge in the background, a dead end that dissolves in light.

The image displayed what living conditions were like in city tenement slums. In Riis's mind, however, photographs were secondary to his written texts and his spoken lectures on the topic of social welfare. Nevertheless, this image exemplified the way in which sites like Mulberry Bend were effectively training grounds for criminal behavior. He wrote: "Like the Chinese, the Italian is a born gambler. His soul is in the game from the moment the cards are on the table, and very frequently his knife is in it too before the game is ended. No Sunday has passed in New York since 'the Bend' became a suburb of Naples without one or more of these murderous affrays coming to the notice of the police". Through his images and words, Riis helped prompt the city to demolish Mulberry Bend and replace it with a park. (This iconic image was recreated almost identically in a scene from Martin Scorsese's film, Gangs of New York (2002), in which gang leader Amsterdam sells a corpse to medical students.)

Gelatin silver print - Museum of the City of New York

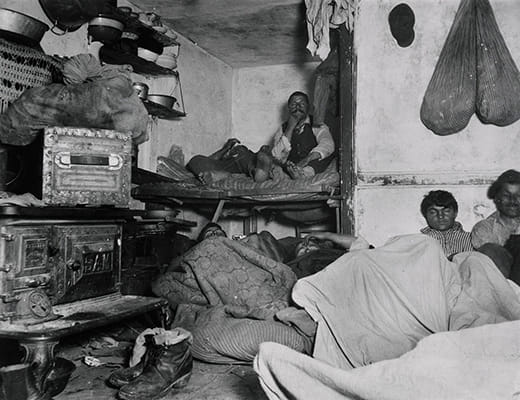

Lodgers in Bayard Street Tenement, 5 Cents a Spot

This photograph shows a tiny, overcrowded, dilapidated, dirty tenement lodging room packed with people and their belongings. Like many of his early photographs, it was taken when Riis accompanied the police on their nightly rounds and raids, where Riis was serving, in his own words, as "a kind of war correspondent". Using flash-bulb photography, Riis woke the drowsy residents suddenly with the bright light and gunshot-like boom of the flash powder. The sanitary police then moved in and raided the illegal lodging house (as city laws of the time required that the minimum cost for a bed, or "spot" be seven cents, but this abode was charging just five cents for floor spots).

As Riis put it, "In a room not thirteen feet either way slept twelve men and women, two or three in bunks set in a sort of alcove, the rest on the floor. A kerosene lamp burned dimly in the fearful atmosphere, probably to guide other and later arrivals to their beds, for it was only just past midnight. A baby's fretful wail came from an adjoining hall-room, where, in the semi-darkness, three recumbent figures could be made out. The apartment was one of three in two adjoining buildings we had found, within half an hour, similarly crowded".

Contemporary criticism has tended to denounce Riis's methods for "victimizing" his subjects, entering lodgings without permission, and startling them with his flash photography. However, his primary intent was to capture honest, candid moments and to advocate for reform in tenement housing. For Riis, the ends justified the means. As he stated, "the half that was on top cared little for the struggles, and less for the fate of those who were underneath". Startling images like this spurred city officials - including then-police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt - to pass laws that made squalid tenement housing safer and more sanitary.

Gelatin silver print - Museum of the City of New York

Baxter St. Court

This photograph shows a small courtyard in a densely populated tenement housing project. Buckets, and a small wooden wagon cart lay on the ground, and two women and seven children sat at the edges of the courtyard looking at Riis's camera. The dingy, cramped scene underscores one of Riis' main messages: places like this are unsuitable for children to grow up in, without even a patch of grass to play upon. He once wrote: "that dismal alley with its bare brick walls, between which no sun ever rose or set, was the world of those children. It filled their young lives. Probably not one of them had been out of sight of it". He added that "Has a yard of turf been laid and a vine been coaxed to grow within their reach, they are banished and barred out from it as from a heaven that is not for such as they. I came upon a couple of youngsters in a Mulberry Street yard a while ago that were chalking on the fence their first lesson in 'writin'. And this is what they wrote: 'Keeb of te Grass.' They had it by heart, for there was not, I verily believe, a green sod within a quarter of a mile". His efforts culminated in the city creating more parks near slums.

The clothesline in this and other images by Riis are of great symbolic importance. As he himself had lived in immigrant slums, tenement housing, and even the streets, upon his arrival in New York, Riis was intimate with the nuances of the living conditions for the poor and needy. When he later found himself in a better financial position and set out on his mission to document tenement housing and slums in New York through photography, he recalled an early encounter when he was attempting to photograph a tenement house and was initially annoyed at the way the clotheslines obstructed the view in the image. Soon, however, he recognized them as "evidence that someone was trying to keep clean" and wrote that "The true line to be drawn between pauperism and honest poverty is the clothes−line. With it begins the effort to be clean that is the first and the best evidence of a desire to be honest".

Gelatin silver print - International Center of Photography

The Potter's Field - The Common Trench

This image shows six workers in the process of burying dead tenement residents and homeless individuals in a trench in Potter's Field, a mass grave for the poor and the immigrants who had been forgotten by society. As he wrote, "even there they do not escape their fate. In the common trench of the Poor Burying Ground they lie packed three stories deep, shoulder to shoulder, crowded in death as they were in life, to 'save space;' for even on that desert island the ground is not for the exclusive possession of those who cannot afford to pay for it". In his writing and lectures, Riis not only appealed directly to his audience's sense of human dignity, but also introduced facts, figures, and images that were undeniably deplorable, such as the fact that the infant mortality rate in tenements was one in ten, and the fact that a full one-tenth of New York City's population would be buried (and forgotten) in the mass unmarked graves of Potter's Field.

In 2018, anthropologists began unearthing the remains at Potter's Field. Manhattan council member Mark Levine stated that "Every one of those bones belongs to a human being, to a New Yorker. People who in many cases were marginalized and forgotten in life. They've been again marginalized and forgotten in their final resting place, and this disinterment is the ultimate indignity". Generations later, many still hope to find the remains of their lost grandparents and great-grandparents at the site.

One of those descendants was Carol DiMedio who set out to trace the final resting place of her Italian immigrant grandfather. She learned from her mother, Annette Gallo, that when she was a ten-year-old girl, she received a letter from her brother (Carol's uncle) who, like her, had been placed in an orphanage (their mother having died giving birth) in which he wrote only "Last Wednesday morning something bad happened to papa". Carol and her mother made it their life-long quest to learn of their grandfather's fate. Yet, upon learning that he had been buried in "The Common Trench", Carol couldn't bear to bring her mother the awful truth: "I lied to her when I told her I found out where he was buried. I told her he is buried in the most beautiful place with trees and green grass surrounded by blue water with seagulls flying above. She cried when I told her. She needed that peace".

Gelatin silver print - International Center of Photography

Chinatown Opium Joint

For this photograph, Riis entered a Chinatown opium den and captured two Asian individuals, one standing, only half visible, looking at the camera on the right-hand side, and the other laying down on a bed, looking off to the right, presumably in an opium-induced stupor. Images like this contributed to his philanthropic project but, coupled with his writings, it also points to racial prejudices and stereotypes that by modern standards appear very much outdated.

Riis's most influential book, How the Other Half Lives, was in fact separated into chapters that focused on specified ethnic groups such as "The Italian in New York", "Chinatown", "Jewtown", and "The Bohemians". As curator Bonnie Yochelson notes, "That was a pre-established literary genre, which he was borrowing. It had a lot of entertainment value. 'Come see the colorful Italians and the mystifying Chinese'". For Riis, "the Jew" had a "low intellectual status" when compared to "the Italian" who "makes less trouble", the "contentious Irishman" or, the "order−loving German". Of the Chinese (for him a catch-all term at the time for anyone of "Oriental" or East Asian appearance) he wrote that "I state it in advance as my opinion, based on the steady observation of years, that all attempts to make an effective Christian of John Chinaman will remain abortive in this generation; of the next I have, if anything, less hope. Ages of senseless idolatry, a mere grub−worship, have left him without the essential qualities for appreciating the gentle teachings of a faith whose motive and unselfish spirit are alike beyond his grasp".

The historian Daniel Czitrom stated that "One of the things that makes Riis so fascinating are these contradictions in his work. I see Riis more as a transitional figure. He's somebody that did bring with him those stereotypes and sort of racialized thinking of the day, but he's also somebody that began insisting on the importance of environment. Or, as he put it at one point, it's the squalid houses that make for squalid people". Czitrom concluded that, "I've always been struck by the tension between the empathy and sympathy that's powerfully depicted in many of those images, and the kind of stereotypes, racial language, that he uses in the text. There's a tension between the text and the photographs. Today, no one really reads Riis anymore, and yet the photographs remain incredibly moving".

Silver gelatin print - Museum of the City of New York

"I Scrubs" - Little Katie from the West 52nd Street Industrial School

After publishing How the Other Half Lives, Riis changed his approach, spending more time building a rapport with his subjects and learning of their life stories. He began taking portrait photographs, often of children who lived and worked in New York's slums. Pictured here is eight-year-old Katie, who took on the motherly duties of caring for her four siblings who worked in a hammock factory (their mother had passed away and their father had taken off with another woman). Katie also attended one of the twenty-one industrial schools established by the Children's Aid Society between 1854 and 1874. The Society was established in order to offer academic and technical training, medical care, and recreational programming to children who, due to their level of poverty, could not attend regular state schools. The image and an accompanying text were included in Riis 1892 book The Children of the Poor.

Riis wrote about his encounter with Katie, "This picture shows what a sober, patient, sturdy little thing she was, with that dull life wearing on her day by day [...] She got right up when asked and stood for her picture without a question and without a smile. 'What kind of work do you do?' I asked, thinking to interest her while I made ready. 'I scrubs,' she replied, promptly, and her look guaranteed that what she scrubbed came out clean". The Children of the Poor was produced by Riis with the aim of highlighting the plight of poor and immigrant children, and recommendations on how their situation could be ameliorated. With the support of the Health Department, Riis filled the book with statistical information on public health, child labor, infant mortality rates, access to education, and crime. At the same time, the photographs and stories were more finely detailed and the book moved many to action, including churches and families who fostered children that had been abandoned at foundling hospitals.

Wrote Riis: "Nothing is now better understood than that the rescue of the children is the key to the problem of city poverty, as presented for our solution today; that character may be formed where to reform it would be a hopeless task. The concurrent testimony of all who have to undertake it at a later stage: that the young are naturally neither vicious nor hardened, simply weak and undeveloped, except by the bad influences of the street, makes this duty all the more urgent as well as hopeful".

Gelatin silver print - Museum of the City of New York

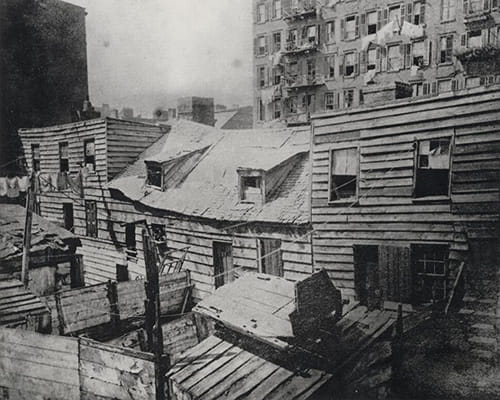

Dens of Death

There is no human presence in this image. The housing looks utterly unfit for human inhabitance (or even to pass through). We see a series of shanty homes running along Baxter Street, all of which look like they could collapse in on themselves at any moment. This photograph appeared in Riis's 1892 book The Battle with the Slum, which he proposed as a sequel to How the Other Half Lives (1890). The former expanded upon the same topics as the latter but with most of Riis's photographs focused solely on the dilapidated buildings themselves.

Riis wrote of these inadequate excuses for housing: "They had been built only a little while when complaint came to the Board of Health of smells in the houses. A sanitary inspector was sent to find the cause. He followed the smell down in the cellar and, digging there, discovered that the waste pipe was a blind. It had simply been run three feet into the ground and was not connected with the sewer. The houses were built to sell. That they killed the tenants was no concern of builder's. His name, by the way, was Buddensiek. A dozen years after, when it happened that a row of tenements he was building fell down ahead of time, before they were finished and sold, and killed the workmen, he was arrested and sent to Sing Sing [prison] for ten years, for manslaughter". Riis also drew attention the wave of typhoid that was caused by contaminated water and which swept through these residences at an alarming rate. It was no doubt a subject close to Riis's heart since he had lost several siblings to poor sanitation in his own childhood in Ribe, Denmark.

materials - Museum of the City of New York

Biography of Jacob Riis

Childhood and Education

Born in the small and poor town of Ribe on Denmark's south-west Jutland, Jacob A. Riis was the third of fourteen children born to schoolmaster and journalist Niels Edward Riis and homemaker Carolina Riis (née Bendsine Lundholm). Several of Jacob's siblings died in early childhood from disease due to unclean drinking water and tuberculosis (in fact Jacob was one of only four Riis siblings to pass the age of twenty), yet despite these tragedies, Jacob recalled a happy childhood. Niels Riis encouraged his son to learn English by reading Charles Dickens and James Fenimore Cooper. Niels had hoped that Jacob might become a writer, but the boy aspired to be a carpenter and on leaving school took up an apprentice with a local carpentry company.

Still aged just sixteen, Riis fell in love with Elisabeth Gjørtz, the twelve-year-old daughter of the owner of the carpentry company. Elizabeth's father showed his disapproval by sending Riis to Copenhagen where he completed his apprenticeship. In 1868, Riis returned to Ribe but found a shortage of work and thus decided (like roughly one third of Denmark's population in the mid-nineteenth century) to emigrate to the United States. Upon his arrival in New York, on June 5, 1870, the twenty-one-year-old Riis's worldly possessions amounted to $40 (gifted by friends), letters of introduction to the Danish Consul, and a locket containing a strand of Gjørtz's hair (which had been given to him by the girl's mother).

On his first day in New York, an anxious Riis spent half of his money on a revolver for the purposes of self-defense. By day five, he was penniless and took on work as a carpenter at Brady's Bend Iron Works on the Allegheny River. He was employed there for only a few days before switching to work as a miner (as it paid more). However, Riis found the conditions in the mine so miserable he soon returned to Brady's.

On July 19, 1870, Riis learned that France had declared war on Germany and decided he wanted to return to Europe and join the French army. However, the French Consulate informed him that they had no plans to send a volunteer army from the US. Despondent. A downhearted Riis pawned his revolver and walked until he collapsed from exhaustion at Fordham College, where a Catholic priest took him in and gave him a bed and a meal. He then carried on his trek to Mount Vernon where he worked odd jobs on farms. He read in the New York Sun that soldiers were in fact being recruited for the war, and returned to New York City to enlist, but his application was refused.

Riis spent several months living destitute, scavenging food, and sleeping out-of-doors or in the rancid-smelling police lodging-house where his cherished locket was stolen from him while he slept. His only companion for a time was a stray dog. For a six-week period he worked at a brickyard in New Jersey, before returning to New York to try, again unsuccessfully, to enlist. Completely disillusioned with New York, he made his way to Philadelphia by working odd jobs to purchase passage on ferries, and sometimes even stowing away on freight trains.

Once he arrived in Philadelphia, Riis reached out to the Danish consul Ferdinand Myhlertz and his wife, who took Riis in and cared for him for two weeks. Riis then found work as a carpenter (among other jobs) in Scandinavian communities in Southern Pennsylvania. Having achieved a modest level of financial stability, he found enough time to try his hand at writing. He tried, unsuccessfully, to get a job at a newspaper in Buffalo, and was also rejected by several magazines. In the following months, he moved between New York, Chicago, and Pittsburgh, often being exploited and cheated by employers and associates. While bedridden with a fever in Pittsburgh, he received the heartbreaking news from home that his beloved Elisabeth was engaged to a cavalry officer.

Early Career

Back in New York once more, Riis successfully applied for the post of city editor for a Long Island newspaper. However, he soon discovered that the editor-in-chief was a dishonest and difficult man and left the position after only two weeks. His luck changed, however, when he gained employment as a trainee at the New York News Association. He wrote passionately about the immigrant communities he had lived amongst, and did his job so well, Riis was soon promoted to the role of editor of a political periodical.

That publication went bankrupt around the same time that Riis received word from home that his older brothers, his aunt, and Elisabeth Gjørtz's fiancé, had all died. He wrote to Elisabeth asking for her hand in marriage, and then, using his $75 of savings and promissory notes, purchased the defunct newspaper. He quickly found success - using the publication to defame his former employers, most of whom now held political positions - and was able to pay off his debts.

Riis received a response from Elisabeth who asked him to come to Denmark so they could discuss his proposal; "We will strive together for all that is noble and good", she wrote. Around the same time, the politicians whose reputations had suffered through Riis's pen, purchased his company at five times the price he had paid for it. He arrived in Denmark, finally in a position of financial security, and married his beloved Elisabeth. The couple moved back to New York a few months after the wedding, and Riis began working as editor of The Brooklyn News.

Riis first used the "magic lantern" projector (that projected images onto sheets or screens) to advertise his newspaper. Riis took his "magic lantern" advertisements around the states of New York and Pennsylvania but returned to New York City following an altercation with a group of policemen, and a group of railroad workers on strike. Riis's neighbor, who was city editor of the New York Tribune, then recommended him for a position there. In 1873 he took up the position of police reporter, stationed in a press office across from the police headquarters on Mulberry Street - a criminal slum area known locally as "Death's Thoroughfare".

Mature Period

Inspired by the progressive social reform movements that had initially emerged in the mid-1800s (including Felix Adler's Society for Ethical Culture), Riis strengthened his resolve to use his position to not only report on crime and its links to poverty, but also to try to affect social change. He decided the best way to achieve this was through a combination of the written word and images. Having no talent for drawing, he taught himself the new art of photography. At the time, photographic processes made it difficult to capture images under poor lighting conditions. But in 1887, Riis learned about a new method of "flash" photography, developed in Germany by Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke. They had used a mixture of magnesium, potassium chlorate, and antimony sulfide, to create a flash of light at the moment of exposure.

Riis soon introduced this method to fellow photographers Dr. John Nagle (who was also chief of the Bureau of Vital Statistics in the City Health Department), Henry Piffard, and Richard Hoe Lawrence. The four men essentially pioneered the use of flash photography in the US by documenting the "dark" conditions in New York's slums. They first published their findings anonymously in the New York Sun on February 12, 1888 in an article accompanied by twelve sketches based on the men's photographs.

Riis and his friends gradually modified the flash system, but it was an exhausting process, and Riis soon found himself working alone. In January 1888 he purchased a 4x5 box camera, plate holders, a tripod, and other equipment for developing and printing his images. He spent the next three years photographing New York's tenements and slums at night, capturing the hardships faced by criminals, immigrants, and the poor and destitute. He began to amass an archive of his own works, along with photographs by other "muckraking" photographers (that is, photographers who sought to expose unjust conditions with the goal of bringing about social reform).

Riis submitted his photographs, accompanied by essays, to various magazines, but was met with constant rejection. When Harper's New Monthly Magazine said they liked his photos but not his writing, Riis decided instead to get his message across through public speaking and projecting images through his "magic lantern". Churches appeared to be the ideal venue, but many declined to host him for fear of offending their congregations' sensibilities. Eventually, Riis received sponsorship from Adolph Schauffler of the City Mission Society, Health Department clerk W. L. Craig, and clergyman and writer Josiah Strong, to speak at the Broadway Tabernacle Church. The lectures - illustrated by Riis's images - were a great success and encouraged others to take up his cause. These included the social reformer, Charles Henry Parkhurst, editor at Scribner's Magazine. Scribner's published an eighteen-page article, featuring nineteen illustrations based on Riis's photographs, in its 1889 Christmas edition.

In his writings and lectures, Riis not only outlined in detail the history of the troubling social situation - the development of the tenement housing system in order to "house" the massive influx of foreign immigrants at the time, the negative effects this approach had, and the efforts of the Sanitation Department to investigate and address these issues - but also presented hard facts and figures. Riis also penned distressing stories of individuals and families who struggled to survive within this system, such as the "case of a hard−working family of man and wife, young people from the old country, who took poison together in a Crosby Street tenement because they were tired".

Late Period

In 1890, Riis published his most popular and influential book, How the Other Half Lives, which expanded upon the article published in Scribner's Magazine, and which opened by informing the reader that the story presented therein "is dark enough, drawn from the plain public records, to send a chill to any heart". The book included the illustrations he had used in the article, as well as seventeen photographic reproductions using the halftone reprographic method, making it one of the first books ever to do so. The book was generally well-received and complimented similarly themed works including the Salvation Army treatise, In Darkest England, and the Way Out (1890) by William Booth, and Ward McAllister's book of New York memoirs, Society as I Have Found It (1890).

He also became actively involved at this time in an organization that would become known in the future as the Riis Settlement House. As Denmark's Riis Museum describes: "Strongly influenced by the work of the settlement house pioneers in New York, Riis collaborated with the King's Daughters, an organization of Episcopalian church women, to establish the King's Daughters Settlement House in 1890. Originally housed on 48 Henry Street in the Lower East Side, the settlement house offered sewing classes, mothers clubs, health care, summer camp and a penny provident bank".

Meanwhile, How the Other Half Lives helped to prompt changes in New York legislation that led to improved conditions for immigrants and the poor. As curator and art historian Lisa Hostetler notes, not only was Riis "a pioneer in the use of photography as an agent of social reform, he was also among the first to use flash powder to photograph interior views [...] At a time when the poor were usually portrayed in sentimental genre scenes, Riis often shocked his audience by revealing the horrifying details of real life in poverty-stricken environments. His sympathetic portrayal of his subjects emphasized their humanity and bravery amid deplorable conditions and encouraged a more sensitive attitude towards the poor in this country".

How the Other Half Lives also served as a model for the next generation of muckraking journalists in the early 1900s. Writer and Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who would become US President a decade later, read Riis's book and wrote to him saying: "I have come to help". The two became friends, and Riis led Roosevelt around the streets of New York to show him first-hand the abysmal living conditions he was trying to reform. Roosevelt duly closed the most deprived of the city's police lodging facilities. They also found that during nighttime, nine out of ten patrolmen were not present for their work, leading to reform in policework itself. Roosevelt later referred to (the Dane) Riis as "the best American I ever knew [and] the most useful citizen of New York".

Next, Riis turned his attention toward the condition of New York's drinking water, publishing "Some Things We Drink" (along with six photographs) in the New York Evening Sun on August 21, 1891. He explained "I took my camera and went up in the watershed photographing my evidence wherever I found it. Populous towns sewered directly into our drinking water. I went to the doctors and asked how many days a vigorous cholera bacillus may live and multiply in running water. About seven, said they. My case was made". This, and further articles he wrote on the topic, prompted the city to purchase the area around the New Croton Reservoir and to take steps to avoid a devastating cholera outbreak. His work also prompted the passing of the Small Park Act in 1887, a law that permitted the city to purchase small parks in crowded neighborhoods.

In the late 1890s, Riis used his writing and photographs to call attention to, and enact change regarding, unsafe tenements, classism, and a range of other social and public health and safety causes. His children (daughter Clara, and sons John, Edward, and Roger) all followed their father's lead, working as activists in the name of their father's causes. Riis was now famous enough to publish an autobiography, The Making of an American, in 1901. Also in that year, as the Riis Museum describes, "the King's Daughters Settlement House was renamed the Jacob A. Riis Neighborhood Settlement House (Riis Settlement) in honor of its founder and broadened the scope of activities to include athletics, citizenship classes, and drama".

Sadly in 1905, Riis's wife passed away. The New York Public Library (which houses the Riis archive) records that "Letters Riis received in 1905 relate for the most part to the illness and subsequent death of his first wife, Elisabeth Nielson. Elisabeth had become well known to the American public after the publication of The Making of an American in which she played an important role. The letters and notes of sympathy include many from people who did not know Riis personally, as well as those from prominent persons, including several cablegrams from Theodore Roosevelt".

Riis remarried Mary Phillips two years later. The couple moved to a farm in Barre, Massachusetts shortly after their wedding, and remained there until Riis passed on May 26, 1914. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Riverside Cemetery in Barre. Mary carried on her late husband's mission, becoming, amongst other things, a board member of the Jacob A. Riis Settlement House.

After his death, Riis's photographs were essentially "lost" since he had not considered them to be of much merit in their own right. He did not considered himself a photographer but saw his photographs rather as visual aids that supplemented his articles and public lectures. Only decades later were over 700 negatives and slides found by his son in the attic of Riis's old home in Richmond Hill. He donated these to the photographer Alexander Alland who brought them to the attention of the Museum of the City of New York under whose curatorship their significance to social history was fully realized.

The Legacy of Jacob Riis

Riis is generally considered the first "investigative" journalist, exposing the worst of society's ills with the aim of enacting social reform to ameliorate the situation of thousands of individuals, families, and children who lived in New York City's streets, slums, and tenements. Although he himself never considered his photograph to be of special value, his images have taken on great significance as historical documents and have provided inspiration to future Documentary Photographers. Indeed, by 1900 Riis had established social reform photography as a sub-genre of Documentary Photography. This was highlighted by the National Child Labor Committee who employed Lewis Hine in 1908 to photograph child laborers in a variety of industries throughout the United States. Indeed, Hine's images played a major role in the 1916 Keating-Owen Act, one of the first laws to reform child labor. His legacy lives on and his influence on American Documentary Photography has influenced subsequent generations of documentary photographers including Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Camilo José Vergara.

Revisionist histories have been quick to highlight the racial stereotypes in Riis's writing, and which display attitudes that were very much of their time and place. Faith in his writings has suffered as a result, but his photography stands the test of time as visual evidence (since one always believes the evidence of one's eyes over what they are told) of the downsides of the rise of industrialization and urbanization. Moreover, within two decades of the publication of How the Other Half Lives, the worst of New York's slums were torn down; new building codes were passed to improve safety and health; all tenement areas were required to have playgrounds; and all households required to have indoor showers and toilets. Today Riis legacy is kept alive through The Jacob A. Riis Settlement House, now situated in Queens, New York. The organization (established in his name in 1901) provides immigration and education services and participates in cultural exchange programs with Riis's homeland, Denmark.

Influences and Connections

- Adolf Miethe

- Johannes Gaedicke

- Henry Piffard

- Richard Hoe Lawrence

- Early Photography

-

![Dorothea Lange]() Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange -

![Ansel Adams]() Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams -

![Walker Evans]() Walker Evans

Walker Evans ![Lewis Hine]() Lewis Hine

Lewis Hine- Camilo José Vergara

- Henry Piffard

- Richard Hoe Lawrence

Useful Resources on Jacob Riis

- Jacob Riis (55)By Bonnie Yochelsem

- Jacob Riis's Camera: Bringing Light to Tenement ChildrenOur PickBy Alexis O'Neill

- The Other Half: The Life of Jacob Riis and the World of Immigrant AmericaOur PickBy Tom Buk-Swienty

- Rediscovering Jacob Riis: Exposure Journalism and Photography in Turn-of-the-Century New YorkOur PickBy Bonnie Yochelson and Daniel Czitrom

- How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New YorkOur Pick

- The Making of an American

- Out of Mulberry Street: Stories of Tenement life in New York City

- The Battle with the Slum (New York City)

- Theodore Roosevelt, the Citizen

- A Ten Year War

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI