Summary of Auguste Rodin

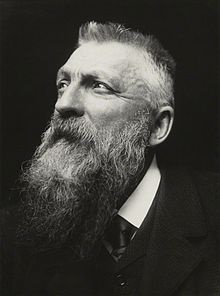

Rodin's genius lay in the way he took the classical sculpted figure and gave it an animation and vitality that helped define the modern age. His work shaped the future of sculpture, with his most famous pieces, The Thinker, The Kiss, and The Gates of Hell, sitting proudly amongst the most iconic in the canon of modern art. His controversial monuments to greats of French literature, meanwhile, carry a raw, unpolished, intensity that brought sculpture into line with the aesthetic revolution that made Paris the center of the contemporary artworld. Having withstood early critical disapproval, Rodin would rise up to achieve a level of international fame and popularity that was unprecedented for a sculptor. Indeed, by the time of his death, Rodin was being likened to Michelangelo. His status as the father of modern sculpture remains undiminished and unchallenged.

Accomplishments

- Rodin stripped away many of the narrative references to classical myth that were still attached to the art of sculpture in the late 19th century and placed a new stress on the dignity of simple human moments. Rather than representing gods or muses, he sculpted lifelike figures with distinctively modern attitudes towards love, thought, and physicality.

- Rodin's achievement as a sculptor was to find a way to make the brute density of sculpture express the fleeting mobility of the human form. To achieve this, he abandoned the polished and idealized figures associated with classical sculpture, and produced rougher, unfinished surfaces, which better expressed restlessness and spontaneous movement. While this technique suggests psychological agitation, it also evokes the transient mood of modern times, which was a thematic preoccupation he shared with the Impressionist painters.

- Despite his modern approach to composition, Rodin's art shows a strong respect for the history and conventions of the medium of sculpture. He favored traditional materials, including bronze, marble, plaster, and clay, but a hallmark of Rodin's modernist style was to draw attention to (rather than smooth out) the lines left by his mallet and chisel.

The Life of Auguste Rodin

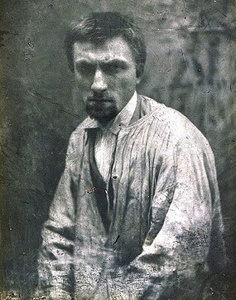

Here we see Rodin as the revered master of sculpture, a standard that all future sculptors measured against.

Important Art by Auguste Rodin

The Age of Bronze

Art historian John Rothenstein wrote in 1958 that "Today Rodin is acknowledged as the greatest master of the modern world [but when he made The Age of Bronze] he was entirely unknown [and] undertook it in the hope it would establish his reputation in Paris. His original idea, drawn perhaps from the recent defeat of France [in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870], was that it should represent a defeated figure, and he called it The Conquered, and under this title it was first shown in Brussels, where it was modelled. Later on, however, it seemed to the sculptor it had assumed a character of its own which demanded the title of Man awakening to Nature, and finally, The Age of Bronze, titles suggested to him perhaps by his own wanderings in the country and the nature/workshop of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a writer for whom he had a particular admiration. The figure does indeed appear to represent a young man at the moment of awakening to the consciousness of being."

The Age of Bronze is the earliest surviving example of a life-sized sculpture by Rodin. He began working on it before leaving for Italy in late 1875 and completed it after his return the following year. A young army telegraphist named Auguste Neyt was the model for this sculpture, providing the first great succès de scandale ("success of a scandal") of Rodin's career. The composition and rough surface of the figure were unconventional by academic standards. The subject also remained obscure - the title only vaguely suggesting classical art - and prompted confusion among critics: rather than clothe his image of man in respected symbolism, Rodin had presented a common man, naked (Rothenstein suggests that Neyt's left hand originally held a staff, possibly to support himself "during his endless posing").

In 1877, the plaster was exhibited in Brussels and Paris, where it was met with derision. Indeed, in Paris, Rodin faced accusations of fraud: that the figure's musculature was rendered with such subtlety it must have been cast directly from Neyt's body. The false charges, which caused Rodin acute distress, were in fact a masked testament to his sublime talent and Rodin was finally able to disprove the claim of fraud with photographic records from his studio. Eventually a group of prominent artists signed a letter of support for Rodin which they presented to the French government. The French state ultimately bought The Age of Bronze, and had it cast in bronze. It was placed in the Luxembourg Gardens, with the authorities too afraid to display in the main (Luxembourg) Museum.

Bronze - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Gates of Hell

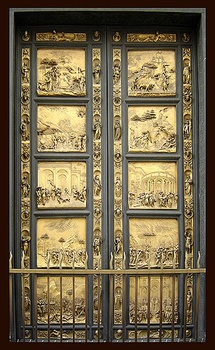

Rodin was commissioned in 1880 to create a set of doors for the planned, though never realized, Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris. Rodin chose to draw on Dante Alighieri's medieval poem about the portal to hell, Dante's Inferno, for his subject matter. It was an attempt to rival (or, rather, complement) Lorenzo Ghiberti's magnificent bronze doors for the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, the Gates of Paradise (1425-52) (the competition of which is often cited as announcing the Renaissance age). Rodin said of the project, "[The artist] must celebrate that poignant struggle which is the basis of our existence, and which brings to grips the body and the soul. Nothing is more moving than the maddened beast, perishing in lust and begging vainly for mercy from an insatiable passion." Despite the collapse of the original commission, Rodin worked intensely on The Gates for several years, but having then failed to complete the work for the 1889 Exposition Universelle, Rodin stopped working on the project (but without ever giving up on the plan to complete it at a future date). The work as it is today, features some 200 individual figures.

Some of his figures formed the basis for famous free-standing works, including The Thinker and The Kiss. It is thought that Rodin initially planned to split the composition into a series of panels (as Ghiberti had done) but after looking at images of Michelangelo's Last Judgment (1534-41), he seemed to favor a more fluid arrangement. Towards the end of his life, with Rodin involved in the planning of a museum devoted to his life's work, he began work on a new plaster model of The Gates of Hell. However, Rodin's failing health, and the outbreak of World War I, put an end to his plans to carve the work in marble. Historian Rosalind Krauss writes, "At the time of Rodin's death The Gates of Hell stood in [Rodin's] studio like a mammoth plaster chessboard with all the pieces removed and scattered on the floor. The arrangement of the figures on The Gates as we know it reflects the most current notion the sculptor had about its composition, an arrangement documented by numbers pencilled on the plasters corresponding to numbers located at various stations on The Gates. But these numbers were regularly changed as Rodin played with and recomposed the surface of the doors; and so, at the time of his death, The Gates were very much unfinished."

On seeing the bronze cast at the Musée Rodin (produced for the museum by the famous Fonderie Alexis Rudier, in 1928), the American sculptor and author T. H. Bartlett wrote, "The first impression is one of astonishment and bewilderment: astonishment at the size of the door and the style of its design, and bewilderment at the extent and variety of the forms that compose it [...] It is like looking into another and strange world. And it is only after repeated visits that this impression is succeeded by the more gratifying one of wonder and admiration of the prevailing life of the figures and the fine sense of true sculpture that everywhere abounds. All idea of subject, illustration, or purpose takes a second place in the mind, or is forgotten, in presence of the charm, the sensibility, the divine touch of art that takes possession of the beholder. He stands like one willingly enchanted in an atmosphere created by the wand of a magician."

Bronze - Musée Rodin, Paris

The Thinker

Although The Gates of Hell was not completed in Rodin's lifetime, his work on the project did inspire other individual works. The Thinker (Le Penseur) is perhaps the most famous example of these. Deriving from a figure at the top of the sculpture who gazes with melancholy over the hellish scenes below him, it originally represented Dante Alighieri, the author of the Divine Comedy (inspiration for The Gates of Hell). Influenced by Michelangelo, the figure is in fact symbolic of modern, secular man - strong in mind and body, but lonely and doubtful in the position he has created for himself as master of his own universe. Although the seated figure is lost in deep thought, the dynamic pose gives him a sense of movement. At first glance, the pose appears natural, but in fact the man's right arm on his left knee is twisted in an exaggerated fashion. "What makes my Thinker think," said Rodin, "is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils, and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back, and legs, with his clenched fist and gripping toes."

Christies auction house writes, "In its final form, Le Penseur [The Thinker] depicts a man with a mature, lined face and a rugged, powerful body. His knobby musculature, hunched posture, and rocky seat derive from the ancient Belvedere Torso; his head is lowered and his chin rests against his hand, a traditional posture of meditation and introspection dating back to Dürer's influential engraving Melencolia (1514). Although the brooding power of Le Penseur recalls works such as Michelangelo's Il Pensieroso, which Rodin had admired on his trip to Florence, a sense of suffering and struggle now supplants the calm immobility of Michelangelo's muscular intellectual. The novel, cross-wise pose that Rodin exploits - the right elbow resting on the left knee - creates an effect of unmitigated self-absorption, while the curved back, straining shoulders, and pulsing veins accentuate the total effort required of mind and body alike to resolve a difficult problem."

Although it had already been exhibited in Copenhagen and Geneva, Christies explains that "The sculpture began its astonishing rise to fame in the early years of the twentieth century, when Rodin enlarged it to colossal proportions, as well as reducing it to smaller sizes." (The Musée Rodin records 17 bronze casts of Le Penseur at its original, and present, scale that were produced during Rodin's lifetime by the foundries Griffoul, François Rudier.) Rodin first showed the monumental figure in public at the Paris Salon in 1904 "where it aroused such wide-reaching enthusiasm that Gabriel Mourey, editor of Les arts de la vie, launched a public subscription to purchase it for the State. Donations streamed in from all quarters, and the colossal bronze was installed in front of the Panthéon in 1906". By this time The Thinker had left behind all associations with The Gates of Hell. As Mourey wrote, "We have chosen this magnificent work from among all the others because it is no longer the poet suspended over the gulfs of sin and expiation, crushed by pity and terror at the inflexibility of a dogma, it is no longer the exceptional being, the hero; it is our brother in suffering, in curiosity, in thought, in joy, the bitter joy of seeing and knowing; it is no longer a superhuman being, one predestined, it is simply a man of all times."

Bronze - Musée Rodin, Paris

The Kiss

Perhaps Rodin's most popular work (although Rodin himself would dismiss it as "a large sculpted knick-knack following the usual formula"), The Kiss features a naked man and woman locked in a candid and passionate embrace. As art historian Alastair Sooke describes, "With sleek and supple bodies, which provide a striking contrast to the roughly chiselled rock on which they sit, Rodin's sweethearts appear timeless and idealised: a universal representation of sexual infatuation, oblivious to all else." The sculpture originally represented Paolo and Francesca, two characters from Dante's Divine Comedy who fall for each other as they read the twelfth-century love story of Lancelot and Guinevere. They are discovered in the grip of their romantic reverie by Francesca's husband (and Paolo's brother) who stabs them to death. The young lovers are then condemned to wander eternally through the corridors of Hell. Rodin intended (what is now known as) The Kiss to feature as a bas-relief on the lower left door on his monumental bronze sculpture The Gates of Hell. However, as Musée Rodin explains, "Rodin decided that this depiction of happiness and sensuality was incongruous with the theme of his vast project. He therefore transformed the group into an independent work [...] The fluid, smooth modelling, the very dynamic composition and the charming theme made this group an instant success. Since no anecdotal detail identified the lovers, the public called it The Kiss, an abstract title that expressed its universal character very well."

Only three larger-than-life marble versions of The Kiss were commissioned during the artist's lifetime. One for the French government, another for the Danish brewer and art collector, Carl Jacobsen, for the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (museum) in Copenhagen, and a third for an eccentric American collector living in England. Focusing on the latter, Sooke tells how, in 1900, the "Bostonian antiquarian and connoisseur" Edward Perry Warren, who was living with his lover, John Marshall, in Lewes, East Sussex (Southern England), approached Rodin to produce a marble replica of The Kiss for his private collection. For a fee of 20,000 francs, Rodin accepted the commission and agreed to Warren's one stipulation that "the genital organ of the man must be completed [in the Greek tradition]." The finished work was delivered in the summer of 1904, but it proved too large for Warren's house and was stored in a stable (there is some conjecture amongst historians that Warren did not like the sculpture because it did not meet with Warren's erotic expectations). Sooke adds that, during the First World War, Warren loaned the sculpture to Lewes Town Hall, "But the indecency of its nude protagonists proved so offensive to puritanical locals, who feared that it would incite lewd behaviour among [locally billeted] soldiers, that it was surrounded by a railing and covered with a sheet [of tarpaulin]. Two years later, it was returned to Warren and hidden by hay bales, to protect it ..."

The story behind how The Kiss then came to enter the Tate's collection is a surprising one given its status today as one of the museum's most prized and popular permanent exhibits. Warren died in 1928 at which point The Kiss was put up for auction. However, it failed to reach its asking price and was placed in storage. Later, in 1952, the Tate launched a public appeal for donations to buy the sculpture for the British nation, which it did for the bargain price of £7,500. Commenting on the sale, indeed, the French weekly paper, Dimanche, published a cartoon with the caption "A kiss that's worth £7,500 ...That's expensive for a kiss - Yes, but it lasts a long time."

Marble - Tate Britain, London

Burghers of Calais

The Burghers of Calais is Rodin's best-known public monument and commemorates the valor of six leading citizens (the burghers of the title) of the French coastal city of Calais where today it stands outside the town hall. In 1347, at the beginning of the Hundred Years' War, the barefoot burghers, each wearing a sackcloth and rope halter, had offered themselves as permanent hostages to the English King Edward III if he would cease his siege of the city. Although earlier artists had focused on the oldest burgher, Rodin chose to include all six. Moreover, the figures are arranged on one level, rejecting the "pyramid" composition typical of figure groups at the time. Rodin also chose to portray the resigned desolation and inner turmoil of the six burghers, thereby challenging the heroic narratives that usually characterized such monuments. (The burghers were, in fact, later spared thanks to the intervention of the pregnant English queen Philippa, who feared that their sacrifice would bring bad luck to her unborn child.)

Hirshhorn Museum Curator Valerie J. Fletcher writes, "Unlike traditional monuments, which showed heroes striding forward proudly, Rodin depicted the men's profound anguish at leaving their homes and families. He distorted the figures to express emotional trauma: the enlarged hands and feet emphasize their melancholy gestures and faltering steps, the tautened muscles convey a sense of physical stress, and the deeply sunken eyes and furrowed brows express heart-rending torment." Fletcher adds that, "The novel idea that heroic deeds are performed at great sacrifice by average people infuriated the Calais authorities, who reluctantly accepted the monument in 1895 but refused to place it in front of the town hall until 1925." Today it is as a universal emblem of civic sacrifice, with one version standing outside London's Houses of Parliament. Rodin's vision also set a precedent for later commemorations of the heroic deeds of ordinary soldiers, such as Felix de Weldon's, Iwo Jima Memorial (1954), (depicting five regular marines raising the US flag at Iwo Jima in WWII), and Maya Lin's, Vietnam Veterans Memorial (1982) (consisting of black granite panels containing the names of the more than 58,000 soldiers who died in the Vietnam War, in chronological order of their deaths).

Bronze - Calais, France

The Hand of God

The Hand of God represents Rodin's attempt to compare the art of sculpting with the divine gift of creation itself. It depicts a right hand, emerging from the earth, holding a block of clay from which two figures - a foetal Adam and Eve - are being modeled. Rodin said of the piece "When God created the world, it is of modeling he must have thought first of all." Originally modelled in clay, the marble version carries technical and symbolic significance. The former is expressed in the way Rodin "under-worked" the stone; the latter relates to his focus on hands (and others on this theme he made during the 1890s, The Cathedral and The Secret). Indeed, Rodin made many clay studies of hands and spoke of the "intense passion for the expression of the human hands" when modelling whole figures.

The sculpture represents Rodin's interest in synecdoche (using a part to represent a whole, like using just a hand to represent an entire person) The piece pays homage to the work of Michelangelo. For the Renaissance master, the latent figure was entombed in the marble and could only be brought to life through the sculptor's divine intervention. Indeed, the piece owes an indirect debt to a trip Rodin made to Italy in 1876 where he studied first-hand the works of the great sculptor, whose unfinished figures materi alized out of rough stone (thereby equating the hand of God with the creative hand of the sculptor).

The art historian E. H. Gombrich says of this work, "[Rodin] became an acknowledged master, and enjoyed public fame as great as, if not greater than, that of any other artist of his time. But even his works were the object of violent quarrels among the critics, and were often lumped together with those of the Impressionist rebels [...] Like the Impressionists, Rodin despised the outward appearance of 'finish'. Like them, he preferred to leave something to the imagination of the beholder. Sometimes he even left part of the stone standing to give the impression that his figure was just emerging and taking shape. To the average public this seemed to be an irritating eccentricity if not sheer laziness. Their objections were the same as those which had been raised against Tintoretto. To them artistic perfection still meant that everything should be neat and polished. In disregarding these petty conventions to express his vision of the divine act of Creation, Rodin helped to assert what Rembrandt had claimed as his right - to declare his work finished when he had reached his artistic aim."

Marble - The Metropolitan Museum, New York City

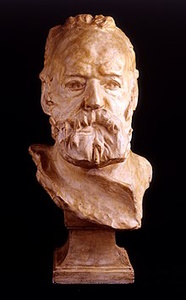

Monument to Balzac

The great post-Napoleonic novelist and playwright, Honoré de Balzac, was one of the founders of the writers' association, Societé des Gens de Lettres. When he died in 1850, the society voted to honor his legacy with a monument. There were four candidates competing for the commission, but it was Emile Zola, the newly elected president of the society, who recommended Rodin for the work. Rodin committed to complete the sculpture within eighteen months. In the end, however, it took him a total of seven years (including six years of preparation) to complete the sculpture. In that time, he traveled to Tours, Balzac's native town, researched the writer's life and work, studied photographs, and posed models who bore a close bodily resemblance to the corpulent Balzac.

Yet, as New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) states, Rodin's ultimate aim "was less Balzac's physical likeness than an idea or spirit of the man and a sense of his creative vitality." For his part, Rodin said of the sculpture, "I think of his intense labor, of the difficulty of his life, of his incessant battles and of his great courage. I would express all that." While most of Rodin's preparatory models were nudes, he finally opted to clothe the author in his baggy writer's gown (resembling a monk's habit), complete with a mound-like protrusion at his crotch to symbolize his virility. MoMA further states, "The effect is to make the figure a monolith, a single upward-thrusting form crowned by the craggy ridges and cavities that define the head and face. Monument to Balzac is a visual metaphor for the author's energy and genius, yet when the plaster original was exhibited in Paris in 1898, it was widely attacked. Critics likened it to a sack of coal, a snowman, and a seal, and the literary society that had commissioned the work dismissed it as a 'crude sketch'." Rodin was quick to defend his work, however: "The Balzac statue is the logical development of my artistic career. I take entire responsibility for it," he declared. Rodin kept his plaster model at his home and did not live to see it cast in bronze. Indeed, it wasn't until 1930 that two bronze copies were cast, with one installed in Paris at the intersection of the boulevards Raspail and Montparnasse in 1939.

Bronze - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The American Athlete

Rodin modelled The American Athlete on Samuel Stockton White III, a key member of Princeton University's gymnastic team who had travelled to England to continue his athletics training at Cambridge and London. In 1899 White won the Sandow Medal which was awarded annually in the UK to the man with the most athletically defined physique. White met Rodin two years later while visiting Paris and offered to model for him. As Christies auction house describes, "Rodin, who had used a fairground strongman as the model for Adam thirty years earlier, was struck by the impressive musculature of White's arms and torso and eagerly accepted the athlete's proposal." White later said of his experience in Rodin's studio: "It was a long time before he was satisfied with the pose. He had me walk around his studio and studied me from all angles. Finally, he asked me to assume a natural pose. I remember sitting on a bench, with my arm resting on my leg as Rodin worked and worked with his infinite sense of detail."

Rodin made two versions of The American Athlete. Here (the first), the head is faced forwards (in the second it is turned to the viewer's left). There are also differences in the musculature which is less pronounced in the later version. In 1904 Rodin instructed the famous Rudier Foundry (run by Alexis Rudier, and the favored foundry of the likes of Rodin, Antoine Bourdelle, Gustave Miklos, Aristide Maillol and Honoré-Victorin Daumier), to make ten bronzes of the original version. White asked to buy one of the bronzes, but Rodin presented it to him as a gift. White, who was later married to the painter, art collector and philanthropist, Vera McEntire (White), became an avid art collector upon his return to Philadelphia and bequeathed the sculpture (with several other pieces from his and his wife's collection) to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Christies offers the views of two historians on the sculpture. The first, John L. Tancock, wrote, "A comparison of The Athlete with The Thinker reveals how profound a change had occurred in Rodin's aesthetic by the early years of the twentieth century. The taut, constricted pose of the earlier work has been replaced by a much more relaxed position. Unlike The Thinker, The Athlete is not brooding on questions of vital importance but is simply in repose between feats of athletic prowess." The second, Albert E. Elsen, adds that "What may have had the greatest appeal to Rodin was White's broad, muscular back, which provided the sculptor with an ample fluid field of mounds and depressions to engage the light. It is the effect of light passing across this rugged terrain that further suggest the incongruity of energy in repose."

Bronze - Philadelphia Museum of Art

Biography of Auguste Rodin

Childhood

François-Auguste-René Rodin was born in a poor area of Paris's fifth arrondissement, to Jean-Baptiste Rodin, an office clerk at the local police station, and Marie Cheffer, Jean-Baptiste's second wife. Despite his father's modest income, Rodin's parents attempted to provide their son with a solid bourgeois grounding by sending him to a boarding school in Beauvais. He was not a successful student, which may have been due in part to his shortsightedness. In 1854, at the age of thirteen, Rodin decided to pursue a career in the arts, attending the École Spéciale de Dessin et de Mathematiques (or "Petite École," to distinguish it from the Grande École des Beaux-Arts), which trained students in the decorative arts.

Early Training

After three years of studying drawing and sculpture, Rodin applied to the Grand École. He passed the drawing competition, but failed three times in the sculpture competition. It seems likely that his interest in naturalism did not fit with the school's academic style. After a third rejection, a dejected Rodin took employment in plaster workshops where he created architectural ornaments. Although he disliked working for a manager, the workshops would provide him with a basic living wage. In 1862, Rodin's sister, Marie, died suddenly. Rodin was so devastated by the tragedy he decided to enter the clergy, and joined the order of the Society of the Blessed Sacrament. In under a year, however, the order’s founder, Father Pierre-Julien Eymard, encouraged Rodin to leave and pursue a career as a sculptor.

In his downtime, Rodin still found the motivation to continue making independent sculptures, including a portrait bust called The Man with the Broken Nose (1863-64). He considered this the best of his work to date and submitted it to the Paris Salon in 1864. His submission was rejected, but against this setback, his emotional wellbeing took an upturn when he met Rose Beuret, a seamstress and laundress, who would become his lifelong partner (she stood by him despite his numerous sexual relationships with other women). In 1866, Rodin and Beuret had a son, Auguste-Eugene Beuret, whom Rodin never recognized legally. Professionally, Rodin accepted a better job too, working on commissions in the workshop of Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse. The steady work and modest rise in income was disrupted by the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Rodin served as an officer until the French surrendered in 1871, and thereafter followed Carrier-Belleuse to Brussels where he worked on decorations for several public monuments.

Mature Period

Having been dismissed by Carrier-Belleuse, Rodin took a trip to Italy. Historians Germain Rene and Michel Bazin write, "In 1875, at age 35, Rodin had yet to develop a personally expressive style because of the pressures of the decorative work. Italy gave him the shock that stimulated his genius. He visited Genoa, Florence, Rome, Naples, and Venice before returning to Brussels. The inspiration of Michelangelo and Donatello rescued him from the academicism of his working experience. Under those influences, he molded the bronze The Vanquished, his first original work, the painful expression of a vanquished energy aspiring to rebirth." It was a rough-edged, unconventional, life-size nude of a common man (possibly a defeated soldier), which he later renamed, and which is known today as, The Age of Bronze (1876).

The Paris salon accepted the work in 1877, but doubts were raised about its authenticity. The figure was so detailed Rodin was accused of casting directly from the model's body. Rodin's protested his innocence and the work was validated following the presentation of photographic evidence (from Rodin's studio), and when The Age of Bronze was subsequently purchased by Edmond Turquet, Under-Secretary of the Ministry of Fine Arts. Now settled in Paris, Rodin's former employer, and newly appointed director of the Sévres porcelain factory, Carrier-Belleuse, asked Rodin for original designs. Rodin lost out in competitions for monuments in London and Paris, but continued to exhibit in Brussels and Paris salons, with the Age of Bronze and St. John the Baptist Preaching (1880) finally establishing his reputation as a sculptor to be reckoned with at the late age (for an artist) of forty.

Confirmation of Rodin's rising stardom came when Turquet commissioned him to create a monumental bronze doorway for a planned museum of the decorative arts. As Christies auction house explains: "Turquet [...] who was eager to demonstrate the progressive stance of the new arts administration [...] granted Rodin a spacious studio at the state-owned Dépôt des Marbres and ample funds to hire models. The sculptor also insisted upon unprecedented autonomy in choosing the format and even the subject matter of the doors. An avid reader of Dante, he had made drawings on Dantesque themes for well over a decade, and his 1876 sculpture Ugolin assis was inspired by the poet's thirty-third canto. 'Dante's Divina Commedia - it was always in my pocket,' Rodin later recalled. 'I read it every time I had a free moment. My head was like an egg ready to hatch. Turquet broke the shell'."

The project is today considered Rodin's magnum opus, even though the planned museum was cancelled, and The Gates of Hell (as the doors later came to be known) were not cast in bronze until after the artist's death. Bazin explains that Rodin's "original conception was similar to that of the 15th-century Italian sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti in his The Gates of Paradise doors for the Baptistery in Florence. His plans were profoundly altered, however, by his visit to London in 1881 at the invitation of the painter Alphonse Legros. There Rodin saw the many Pre-Raphaelite paintings and drawings inspired by Dante, above all the hallucinatory works of William Blake. He transformed his plans for The Gates to ones that would reveal a universe of convulsed forms tormented by love, pain, and death." Probably Rodin's two most famous freestanding figures, The Thinker (1880), and The Kiss (1887), were originally designed for The Gates of Hell.

In 1884 Rodin was commissioned to create his first public monument. It commemorated the sacrifice of ordinary soldiers (rather than heroic generals and leaders), in the town of Calais. The Burghers of Calais focused on the six men (burghers) who offered themselves as hostages to the English king during the year-long siege of 1347. The fact that Rodin chose to stress the "unheroic" dejection and resignation of the men was not appreciated by all, and the monument wasn't placed in its prime site in front of Calais's town hall until 1925.

Around this time, Rodin, who had had many lovers outside his relationship with Beuret, became seriously romantically involved with the figurative sculptor Camille Claudel (sister of poet, Paul Claudel) who joined his studio as an assistant in 1884. Rodin was a great admirer of Claudel's natural beauty and talent, and within a year they were engrossed in a tempestuous affair that lasted until 1892 (though they continued to see each other until 1898). During their relationship, they modelled portraits of eachother and she assisted Rodin on a number of his works (and he on hers). Claudel eventually separated from Rodin when he refused to end his relationship with Beuret. (Claudel's jealousy towards Beuret would develop into symptoms of paranoia and rage and her subsequent, and serious, decline in mental health is well documented.)

Late Years and Death

In 1886, having previously made busts of the great Romantic author, the French state commissioned Rodin to sculpt a monument to one its literary greats, Victor Hugo (author of Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre Dame), who had died four years earlier. Rodin's original nude figure caused such offense amongst officials he was forced to rethink the project. Musée Rodin takes up the story from there: "From 1890 onwards, he worked on two projects: the seated figure he had initially planned, which was unveiled in the gardens of the Palais-Royal in 1909, and another study for the Panthéon, showing Victor Hugo standing [which never came to fruition]. In 1897, he presented his final model, true to his first idea of the poet in his Guernsey exile seeming to gaze at the stormy sea, but portrayed nude, with drapery over his left leg; this gave a heroic quality to the figure, despite his depiction as an old man. He is accompanied by two female allegories (rather than the original three): The Tragic Muse hovers above him, while Mediation (or The Inner Voice) stands behind."

Rodin followed in 1889 with a monument to the famous seventeenth-century Baroque artist, Claude Lorrain, commissioned by the latter artist's hometown of Nancy. Rodin showed Lorrain painting outdoors and gazing skyward. He placed the artist on a pedestal, modeled in the Baroque style, which he embellished with figures of the Olympian god Apollo and his chariot bursting forth to create a new sunrise. Two years later, Rodin was commissioned by the Society of Men of Letters to create a memorial for the poet Honore de Balzac. Instead of taking eighteen month to complete the work (which Rodin had committed to), he became infatuated with his subject, and took seven years to complete the commission. His final vision of Balzac was so unflattering (ergo, naturalistic) that the sculpture was attacked by critics and rejected by the Society. A furious Rodin decided to keep the sculpture for his private collection.

In 1896, Rodin began work on another monument, this time to commemorate the life of the Argentinian President and education reformer Domingo Sarmiento. It would be a "double statue" featuring Sarmiento and, at his feet, the god Apollo vanquishing the Python, creating an allegory for Sarmiento's victory over ignorance and illiteracy. However, the people of Buenos Aires were not taken with the sculpture since it did not conform to the patriotic standard by which national icons were expected to be represented in an uncomplicated, and readily understandable, way.

By now Rodin had achieved such success he was able to purchase a residence and workshop in the Parisian suburb of Meudon where he employed around fifty assistants and students, and welcomed orders from England, Germany, Austria, and America. But having become very wealthy, and still aggrieved by the critical panning he received for the Balzac sculpture, Rodin's personal output slowed. Nevertheless, several exhibitions around the turn of the century brought him more recognition. He exhibited in Belgium and Holland in 1899, and was given his first retrospective in Paris in 1900. Subsequent shows took place in Prague, New York, and Germany. Rodin's legend was sealed when he exhibited no less than 160 sculptures and drawings at the pavilion of the 1990 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Bazin explains that by the turn of the century Rodin was in fact "less a sculptor than an entrepreneur of sculpture. He himself executed only models, of which he made many, while searching for the form that suited him. Casting in bronze was the domain of specialists, but he also delegated the hewing of marble to others, to be executed under his direction but not by him. He was assisted in this 'industrial' enterprise by a series of secretaries, including for a brief period the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke."

In his mature years, Rodin produced The American Athlete. It shows the artist's more relaxed approach toward figure modeling. As the Philadelphia Museum of Art writes, "The Philadelphian Samuel Stockton White III sat for Rodin in Paris in 1901 and 1904, while on breaks from his studies as a bodybuilder. Rodin disliked professional models' tendency to adopt conventional poses and encouraged White to select a pose that felt natural. Recognizing that the modeling sessions might be long, White adopted this seated position that, perhaps unintentionally, recalls Rodin's acclaimed work The Thinker from 1880."

Rodin followed in 1906 with a bust of the famous English playwright, critic, and philosopher George Bernard Shaw (commissioned by Shaw's wife, Charlotte). The National Trust writes, "Two versions were ordered, one in bronze and one in marble [...] Shaw had great respect bordering on veneration for Rodin's skill as a sculptor, considering him to be a modern-day Michelangelo. After donating his home to the National Trust, he joked that Rodin's bust would be remembered 1,000 years hence, while its subject would be 'otherwise unknown'. The bronze sculpture accurately depicts Shaw's appearance, while also suggesting the vitality of his presence."

In 1908 Rodin rented a floor (transforming it into his studio) at one of Paris's most desirable addresses, the Hôtel Biron (which had been home to other famous tenants including Isadora Duncan, Jean Cocteau, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Henri Matisse). He was visited by the English King Edward VII at his Meudon workshop, also in 1908.

In 1912, Rodin sculpted the infamous Russian dancer, Vaslav Nijinsky. London's Victoria and Albert Museum explains, "Rodin was 72 when he sculpted [his] figure that depicts Nijinsky gathering momentum, ready to leap into the air. It does not portray him in any specific role, but instead encapsulates and embodies the astonishing energy Nijinsky brought to a range of characters. [...] Rodin had been present when the Russian dancers made their Paris debut in 1909 and significantly lent his name to an article published in Le Matin in May 1912 defending Nijinsky's controversial ballet L'Après-midi d'un faune. Nijinsky apparently posed for Rodin in July 1912, to thank the sculptor for the support."

Rodin, who had by now taken over the whole of the Hôtel Biron, was engaged in an affair with the Marquise (and later, Duchess) Claire de Choiseul. She exercised great control over Rodin's life at this point. She even handled the sale of his work before she was accused of stealing a collection of his drawings. It is thought that de Choiseul's duplicity convinced Rodin to marry Rose Beuret, which he did in January 1917. Sadly, Beuret died just two weeks after their wedding. Rodin passed away in November of that same year, after his lungs were weakened by a bout of influenza.

Rodin's funeral was held at Meudon where he was laid to rest beside Beuret (The Thinker is laid at the base of his tomb). In the UK, The Times reported on "the funeral of 'the greatest sculptor, who had been one of the highest expressions of the genius of contemporary France" and on the day of Rodin's burial a solemn service was celebrated in his honour at London's Westminster Abbey. Before his death, Rodin reached an agreement with the French government that it acquire the Hôtel Biron (and its wonderful gardens) and convert it into a permanent Rodin Museum (Musée Rodin) in return for his artworks which he bequeathed to the nation. As well as his sculptures, his estate included a vast number of supplementary materials, including illustrations, dry-point etchings, and many explicit drawings of female nudes.

The Legacy of Auguste Rodin

By the time of his death, Rodin was famous the world over. Considered the titan of modern figurative sculpture he was for many the heir-apparent to Michelangelo. As time passed, some critics became more circumspect in their analysis of his oeuvre, taking exception to his lack of formal discipline and his penchant for the decorative. What is beyond dispute, however, is the enormous stylistic influence he exerted over future generations of sculptors. In France alone, Charles Despiau, Aristide Maillol, and Antoine Bourdell all drew inspiration from Rodin's legacy. Today, nearly every large encyclopaedic museum owns a casting of one or more of his sculptures, and exhibitions of his work are held regularly.

The Musée Rodin sums up his legend thus: "Controversies surrounded certain of his works, such as the scandals around The Age of Bronze or the Monument to Honoré de Balzac, and for his unfinished projects, most famously The Gates of Hell, but few who recognize Rodin's sculptures have failed to be moved by them. His genius was to express inner truths of the human psyche, and his gaze penetrated beneath the external appearance of the world. Exploring this realm beneath the surface, Rodin developed an agile technique for rendering the extreme physical states that correspond to expressions of inner turmoil or overwhelming joy. He sculpted a universe of great passion and tragedy, a world of imagination that exceeded the mundane reality of everyday existence."

Influences and Connections

-

![Michelangelo]() Michelangelo

Michelangelo -

![Donatello]() Donatello

Donatello ![Antoine-Louis Barye]() Antoine-Louis Barye

Antoine-Louis Barye

![Émile Zola]() Émile Zola

Émile Zola![Octave Mirbeau]() Octave Mirbeau

Octave Mirbeau

-

![Umberto Boccioni]() Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni -

![Raymond Duchamp-Villon]() Raymond Duchamp-Villon

Raymond Duchamp-Villon -

![Henri Matisse]() Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse ![Michelangelo Antonioni]() Michelangelo Antonioni

Michelangelo Antonioni

-

![Camille Claudel]() Camille Claudel

Camille Claudel ![Rainer Maria Rilke]() Rainer Maria Rilke

Rainer Maria Rilke![Loie Fuller]() Loie Fuller

Loie Fuller![Judith Cladel]() Judith Cladel

Judith Cladel

Useful Resources on Auguste Rodin

- Rodin: The Shape of GeniusOur PickBy Ruth Butler

- RodinOur PickBy Bernard Champigneulle

- Rodin: A BiographyBy Frederic V. Grunfeld

- Rodin: The Zola of SculptureBy Claudine Mitchell

- Auguste Rodin: Sculptures and DrawingsBy Gilles Neret

- Auguste RodinOur PickBy Rainer Maria Rilke

- Auguste Rodin (The Life and Work Of...)By Richard Tames

- Apropos RodinBy Jennifer Gough-Cooper, Geoff Dyer

- Auguste RodinBy Irene Korn

- RodinOur PickBy Raphael Masson, Veronique Mattiussi, Jacques Vilain

- Rodin: A Magnificent ObsessionBy Merrell Publishers

- Auguste Rodin: Drawings & WatercolorsBy Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, Christina Buley-Uribe

- Rodin: The Gates of HellBy Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, Auguste Rodin

- Rodin: His Art and His InspirationBy Catherine Lampert, Antoinette Romain

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI