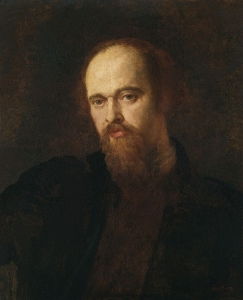

Summary of Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Recognized by history as an inspired but provocative nonconformist, Dante Gabriel Rossetti made his name initially as a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The Brotherhood challenged the "decadent" indulgences of the day by looking for inspiration and religious guidance in medieval art. Rather than produce dramatic historical narratives (as was the fashion of the day), The Brotherhood adhered to an inflexible set of puritanical and aesthetic standards of which Rossetti soon tired. He continued to paint his mythical parables with the same luminosity and attention to the finest picture detail, but Rossetti, who harboured longings to be recognised also the poet, became all-consumed with the idea of female beauty. His licentious lifestyle, though condemned by many of his colleagues, breathed erotic life, and it must be said, genuine personality, into his art. But with time, his destructive lifestyle led to his mental decline, but as often happens with after some time, this merely enhanced his legend as a prodigious maverick of the Victorian age.

Accomplishments

- As a leading light in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood movement, Rossetti looked back to a period before the High Renaissance. He took inspiration in the purity and symbolism of medieval and religious fables found in 15th-century Florentine and Sienese painting

- Rossetti is recognized predominantly as a portraitist. His preference was for religious subject-matter but as he matured as an artist his work proved most divisive because of his habit of using family members and lovers to represent holy icons.

- Rossetti was a founding member of the furnishing and decoration business, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. The company, established in 1861, was admired for their complex and vivacious designs. Though he soon lost interest in decorative arts, and though his relationship with William Morris suffered as a result, Rossetti's designs stand as a tangible link between the Pre-Raphaelites Brotherhood and Morris's Arts and Crafts movement.

- In his later life, Rossetti had wanted to abandon art and pursue his life-long ambition of becoming a poet in the mould of his idols Dante (his namesake), Byron and Keats. However, his published collection was considered by critics to be too verbose and this setback was thought to have contributed to a slowing in his artistic output, and was cited indeed, as a catalyst for his drug addiction and mental deterioration.

Important Art by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin was arguably Rossetti's first mature painting. Completed the year after he had cofounded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (in 1848) Rossetti intended to show the painting that spring at the Free Exhibition at the Hyde Park Corner Gallery. The canvas shows the young Virgin Mary seated at a table with her mother, Anne, as the two embroider a lily. In the background, Mary's Father, Joachim, reaches to prune a vine in a luscious green garden which has been visited by a haloed dove. At the women's feet are a crossed palm branch and thorn. On the left hand side of the picture frame is a child angel who waters a vase with the prop of the lily. The flower rests on a stack of educational books labelled: Charity, Faithfulness, Hope, Prudence, Temperance, and Fortitude.

The childhood of the Virgin Mary was a common subject from medieval religious painting. However, Rossetti chose not to depict a straightforward bible scene but preferring to steep his narrative with luminous colors and symbolic meanings. The dove represents the Holy Spirit, the Vine leaves Christ himself, the Palm and Thorn, Palm Sunday and the Crucifixion, and the Lily represents Mary's purity. The significance of the young Mary embroidering a lily from nature has been commented upon, as it references the Pre-Raphaelites own reverence for the natural world. It also lays a significance on embroidery, and the decorative arts in general, not being a lesser craft (or a mere guild) but rather an important, and even semi-spiritual or meditative, practice.

Another un-orthodox factor of the painting was the way Rossetti used family members as models for the religious figures. The Virgin Mary was based on his sister, Christina, Saint Anne on his mother Frances, and Joachim was modelled on an old family servant known as "old Williams." To use such commonplace models as one's own family and especially servants for holy figures was atypical and daring, and only a few years later fellow Pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais came under harsh criticism for using friends and family and a real carpenter as models for his 1850 work Christ in the house of his parents. Furthermore, The Girlhood of Mary Virgin was the first painting to be inscribed with the initials PRB, on its frame. In fact, Rossetti paid unusual attention to the frame of the painting, showing an early interest in decorating and artistically influencing every aspect of a finished piece. For him, this also involved embelishing the painting with poetry, and he wrote two sonnets to be read alongside the painting; one inscribed on the frame, another in the exhibition catalogue. His goal was to create a double work of art that blurred literary and visual categories.

Oil on Canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Ecce Ancilla Domini

The year after his "reimagining" of the childhood of the Virgin Mary, Rossetti chose to continue his vein of religious scenes by painting the Annunciation; the moment where the Angel Gabriel appeared to the Virgin bringing news of her divine pregnancy. The Latin title quotes the Gospel of St Luke, translated as "Behold the handmaiden of the Lord." Rossetti creates a symbolic consistency by continuing the depiction of the Virgin Mary alongside lilies which were often used as a symbol of purity in Italian Renaissance and Medieval art. Here, indeed, Gabriel presents Mary with the lily as a symbol of her eternal virginity and purity. Both Mary and Gabriel are swathed in virginal white robes with golden haloes, and backed with the rich royal, heavenly blue typically associated with Mary. A rich red panel stands in her bedroom, also with a decorative lily motif.

When the painting was exhibited at the National Institution in 1850, it came in for harsh criticism for Rossetti's brazen re-imagining of the Annunciation. Mary, rather than kneeling for prayer, is depicted in her crumpled bed, in a long, creased white nightgown that was typical of a newly-wedded bride. For his part, Gabriel is shown without wings, and swathed in a loose white gown exposing his bare thigh and hip. Both figures seem ethereal, yet also real flesh and blood (again modelled on Rossetti's own family). A critic from the Athenaeum was caught off-guard by Rossetti's disregard for traditional Annunciation scenes, calling it "a work evidently thrust by the artist into the eye of the spectator more with the presumption of a teacher than in the modesty of a hopeful and true aspiration after excellence." Rossetti never exhibited the painting in public again, and in the 1850s he distinctly turned away from elaborate biblical scenes and towards female portraiture.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Bocca Baciata

By the time he completed Bocca Baciata (in 1859), Rossetti had been in a nine year relationship with Elizabeth Siddal. In that time he produced dozens of adoring sketches of his future wife (they were married in 1860). However, the model for this, the first of his painted female portraits, was not Elizabeth, but his mistress, Fanny Cornforth. Whereas he sketched Elizabeth as a beautiful, ethereal being, Rossetti painted Fanny as his ideal of sensual desire and allure.

Rossetti based his painting of Fanny on a sonnet, Decameron, by the fourteenth century Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio. On the reverse of the canvas Rossetti had inscribed a line from said sonnet, "Bocca baciate non perda ventura, anzi rinnova come fa la luna," which translates as "The mouth that has been kissed loses not its freshness; still it renews itself even as does the moon." Contained by the tight framing, against a flat decorative background, and seen only from face and shoulders up, Fanny has been effectively removed from her environment. Her pink, slightly parted lips are the central point of the frame, and her loose red hair (historically, a sign of loose morality) flows in long ribbons around her shoulders while her unbuttoned blouse reveals bare flesh. And once again calling on religious symbolism (the fable of The Garden of Eden), Rossetti places an apple on the table in front of Fanny thus confirming Fanny's allure and her powers of temptation.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, the painting received a mixed reception, not least from Rossetti's pious Brotherhood colleague Holman Hunt, who described the painting as "gross sensuality of a revolting kind." However, other critics and friends of Rossetti were enthralled by the painting. The poet Algernon Swinburne said that the picture was "more stunning than can be decently expressed" while artist Arthur Hughes commented that it was "such a superb thing, so awfully lovely" that he wouldn't be surprised if the paintings owner (George Price Boyce) tried to "kiss the dear thing's lips away."

Oil on panel - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Stained Glass Panel No.4 in Rossetti's St George and the Dragon sequence, for Morris & Co.

By 1862, Rossetti had become disassociated with the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and formed closer working bonds with William Morris and Edward Burne Jones both of whom appreciated Rossetti's aesthetic sensibilities and his dedication to medieval myth and legend. Rossetti was a founding member in Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co in 1861, and in the ensuing years he worked with the company on its decorative art designs. In 1862 he designed six stained glass panels for the windows at Harden Hall, West Yorkshire relating to the legend of St George and the Dragon (a rare excursion into British medieval history). The Morris & Co company became well known for their complex and vivacious designs, and Rossetti boasted that "Our stained glass may challenge any other firm to approach it."

Rossetti's passion for the legends and romance of the past are captured in the wildness, violence and sensuality of tales such as St George and the Dragon. High quality colored glass was used for the panels, and an innovative color palette was set by Rossetti, drawing on some of his favorite shades; dazzling whites and golds, rich royal reds and olive greens. His narrative cycle for the stained glass designs was vivid and action-filled, with dense decorative pattern in a flat medieval style. In this panel, the princess is tied to a tree, almost swooning, and stripped to the waist, while Saint George, bedecked in gleaming gold armour, slays the Dragon. It is noticeable that the princess, with long pale limbs and lose, wavy flaxen hair, bears a resemblance to many of Rossetti's muses. We also find evidence Rossetti's devotion to poetry and storytelling as each panel is accompanied by a caption in curling, medieval script which read here as: "How the good Knight St George of England slew the dragon and set the Princess free."

After a few years, Rossetti tired of working in the decorative arts, and his relationship with Morris became strained. It is true that he produced fewer pieces than the other founders of Morris and Co.. But his designs show how Rossetti acted as an important link between the Pre-Raphaelites and Morris's Arts and Crafts Movement.

Stained Glass - V&A Museum, London

Beata Beatrix

There is a story about Rossetti that tells how, immediately following the death of his beloved Lizzie, the artist felt a sudden compulsion to create a funerary painting in her honor. This is true to an extent, but Rossetti actually reworked the material of an unfinished portrait into a new composition that became his eulogy to his wife.

Rossetti saw himself as a spiritual descendent of his namesake, Dante Alighieri. The Italian poet had been dedicated to Beatrice Portinari, his muse and inspiration. She appeared as a character in two of his greatest works; La Vita Nuova and the Divine Comedy, and in the latter (written between 1308 and 1320) she is immortalized as a higher, spiritual being, who acts as a heavenly guide for Dante on his journey through Hell. Rossetti preferred to represent, possibly out of a feeling of guilt, an idealized, beautifully mournful version of Elizabeth, rather than try a represent the reality of her addictions and/or the downsides of their tumultuous relationship.

Elizabeth is pictured, not at the moment of her death, but rather in a state of "sudden spiritual transfiguration." She is represented as an ethereal figure, crouching, in a state of ecstasy, as if she is about to receive communion. Her eyes are closed and her head tilted upwards and she is surrounded by a soft golden glow. The rest of the color palette, however, is muted, and as Rossetti's friend F.G. Stephens noted, the grey and green of Lizzie's dress signify "the colors of hope and sorrow as well as of love and life." Yet the painting does feature a darker symbolism in the form of the red dove. The red dove, the symbol of the Holy Spirit coming to take her to the Afterlife, descends on Elizabeth, depositing a poppy in her upturned hands. This feature acknowledges the beauty and deadliness of the Poppy; the flower that brought about her death through Laudanum adiction. The dove also had a personal meaning, as "Dove" was Rossetti's nickname for Elizabeth. In the background, meanwhile, Dante cuts a shadowy figure, facing an indistinct red-cloaked woman who represents Love who holds a flickering candle, as the flame of Beatrice's life begins to fade. As a direct homage to Alighieri, a sundial, surrounded by golden light, points to the time of Beatrice's death: 9 o'clock on the 9th of June, 1290.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Proserpine

By 1874, Rossetti was in the grip of a mental breakdown, a decline not helped by an addiction to chloral hydrate and alcohol. Still residing at 16 Cheyne Walk, he was nursed in the last ten years of his life by Fanny Cornforth, and visited regularly by his lover, Jane Morris. Rossetti had become somewhat obsessed with Morris in fact; the one woman he never fully possessed due to her unhappy marriage to William Morris (with whom, it is said, she stayed married for the sake of their children). However, during 1870s, Rossetti painted many portraits with Jane as his model. Here, with her ruby red lips, thick raven hair, elongated neck, and dressed in a flowing blue silk gown, she is the very picture of elegance. However, though she possess a serene beauty, her expression is distant and she seems somewhat forlorn.

Though Proserpine is dated 1874, it was in fact painted and repainted no less than eight times over the decade which provides a strong hint of Rossetti's obsession with Morris. In this composition, she is refigured as the Goddess Proserpine, whose legend closely mirrored the pair's own relationship. In the myth, Proserpine must travel to the underworld and leave behind her true love, Adonis (Rossetti). While in the Underworld, she unwittingly eats six pomegranate seeds (represented here), obliging her to remain in the Underworld with Hades (William Morris) for six months of the year as his wife. Only in the six summer months can Proserpine return to Adonis in the sunshine of the above world. Like Proserpine, Jane had felt contracted to her marriage but during the summer months, while William Morris was renovating their home, she and Rossetti stayed in Kelmscott Manor where they were free to pursue their love affair.

Proserpine is often viewed as Rossetti's last great painting, completed (not withstanding later alterations) just before he truly descended into mental and physical illness. On the frame of Proserpine, Rossetti inscribed a sonnet which expressed his agonizing feelings towards Jane Morris:

Afar away the light that brings cold cheer

Unto this wall, - one instant and no more

Admitted at my distant palace-door.

Afar the flowers of Enna from this drear

Dire fruit, which, tasted once, must thrall me here.

Afar those skies from this Tartarean grey

That chills me: and afar, how far away,

The nights that shall be from the days that were.

Afar from mine own self I seem, and wing

Strange ways in thought, and listen for a sign:

And still some heart unto some soul doth pine,

(Whose sounds mine inner sense in fain to bring,

Continually together murmuring,) -

"Woe's me for thee, unhappy Proserpine!"

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Biography of Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Childhood and Education

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti was born in May 1828 to Italian emigres living in London. The boy's father, Gabriel Pasquale Giuseppe Rossetti, was a scholar - he was Professor of Italian at Kings College from 1831 - and poet who had been exiled from Italy for his support for revolutionary nationalism. His English-Italian mother, Frances Mary Poldari, was the daughter of an exiled noble Italian scholar who, in addition to her maternal duties, enjoyed a career as a private teacher. The rich literary and cultural background of the couple saw that their passion for learning was passed down to all four their children: Gabriel, Christina, William and Maria. The children were practicing Anglicans but carried with them something of their father's Catholic worldview.

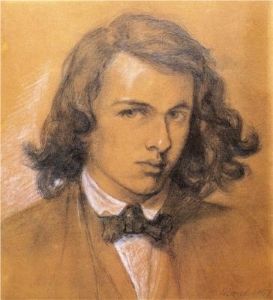

From an early age, Gabriel Charles Dante chose to be addressed by his middle name, Dante, so as to emphasize his affinity with the medieval Italian poet and writer (about whom his father had written extensively). Indeed, Dante had been surrounded by art and literature of medieval Italy, and even as a boy had composed plays and poetry and produced drawings in this vein. Dante was able to develop his precocious talents (for painting and writing) through a combination of home education and schooling at Kings College. He came to love bible passages, Shakespearean tragedies, Edgar Allan Poe and the poetry of Byron. As a teenager he was torn between the ambition to become a poet or a painter and often claimed that his true passion lay with writing and poetry.

Early Work

Rossetti studied at Henry Sass Drawing academy between 1841 and 1845, and then for a further three years at the Antique school of the Royal Academy. By 1848, still aged just twenty, Rossetti had a wealth of practical training behind him, yet he found himself at odds with the Victorian art establishment. To Rossetti, art of the Academy seemed full of sentimental, fussy and moralistic scenes, and staid, snobbish portraits. Rossetti was refreshed rather by the work of Ford Madox Brown - by his attention to detail, his graphic style, and his daring use of color. This style was far closer to the luminous medieval paintings that Rossetti adored. The young Rossetti asked Brown to tutor him, and he maintained a close relationship with the elder painter for the rest of his life.

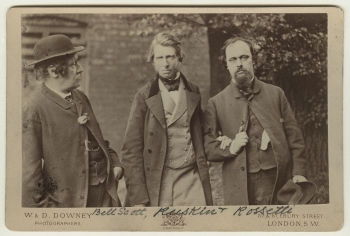

In the mid-1840s, Rossetti attended the exhibition of a painting called The Eve of St Agnes, by a young artist called William Holman Hunt. The painting was an illustration of a little-known Keats poem. Like Holman Hunt, Rossetti was a lover of Keats, and he saw in Hunt a kindred spirit who may share his artistic ideals and wish to confront the vapid face of the Academy. Rossetti and Hunt began to share lodgings in Fitzrovia, and Rossetti became acquainted with a classmate of Holman Hunt's at the Royal Academy of Arts, John Everett Millais. In 1848, the three artists met at Millais parent's house on Gower Street, and formed the first official meeting of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). By the autumn, the Brotherhood had recruited four more members: painters James Collinson and Frederic George Stephens, poet and critic William Michael Rossetti (Dante's brother) and sculptor Thomas Woolner.

The principles of the Brotherhood were manifold and in some ways complex. People like the influential critic John Ruskin had singled out Rossetti as the Brotherhood's de-facto leader, and it was Rossetti who determined to bring together a group of artists who were in actual fact varied and disparate. In his autobiography, however, Holman Hunt insisted that it was he and Millais who were the driving forces behind the birth of the Brotherhood, and that Rossetti was, at heart, a poet (more than a painter). However, it was Rossetti who sought to lay out the Brotherhood's common goals:

1. to have genuine ideas to express;

2. to study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them;

3. to sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote; and

4. most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good pictures and statues.

The Brotherhood sought to return to a time before the dominance of Raphael and the Mannerist artists who followed him; in other words to emulate the spiritual, mythological and medieval while attending to bold colorization and fine picture detail. Complex and symbolic compositions, jewel bright colors, detailed brushwork and poetic and historical references were all factors shared by the artists. The eminent critic John Ruskin wrote: "Every Pre-Raphaelite landscape background is painted to the last touch, in the open air, from the thing itself. Every Pre-Raphaelite figure, however studied in expression, is a true portrait of some living person". Most of all, the Brotherhood scorned the work of Royal Academy founder Sir Joshua Reynolds, who they collectively despised.

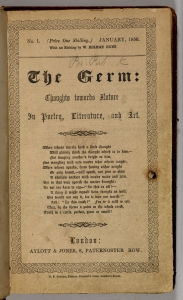

As a way of publishing its writings and poetry, the Brotherhood created its own magazine called The Germ. Not only were the seven members of the brotherhood involved in the publication, but it also became associated with figures such as Christina Rossetti (Dante's sister), Madox Brown, and the critical champion of the movement John Ruskin. The first edition was published in 1850, and the public face of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was born. It proclaimed; "With a view to obtain the thoughts of Artists, upon Nature as evolved in Art [...] this Periodical has been established. [It] is not open to the conflicting opinions of all who handle the brush and palette, nor is it restricted to actual practitioners; but is intended to enunciate the principles of those who, in the true spirit of Art, enforce a rigid adherence to the simplicity of Nature either in Art or Poetry."

Rossetti however courted controversy from the outset. In a series based on the early lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary, for instance, Rossetti used a complex range of biblical symbols and luminous colors to create vivid scenes set in medieval Mediterranean-styled surroundings. Yet, what shocked the viewing public was the way in which the holy figures were depicted as human flesh-and-blood. While the Victorian public may have been willing to accept a stylistic change, they were shocked by the way in which the whole solemn process of painting biblical scenes seemed to have been overturned. Moreover, Rossetti's scenes had a certain Catholic bent to them which set them apart from Anglican British religious painters. They were richly embellished and focused on the most Catholic of religious figures, the Madonna; they embodied a certain "foreignness," or a European sensuality and old-world mysticism, that set him apart even from Hunt and Millais. By the early 1850s, the original PRB had drifted apart, and Rossetti took his work in a new direction.

Mature Period

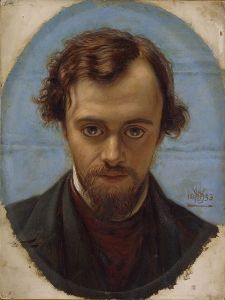

Rossetti turned away from detailed religious scenes, investing instead in his obsession with female beauty, which he explored chiefly through portraiture. Indeed, mythological portraits became most of his life's work, and the goddesses, tragic heroines and saints Rossetti brought to vivid life were based around a handful of lovers and muses. Rossetti was enthralled most ecstatically with Elizabeth Siddal. In 1850, Dante met Siddal, herself an aspiring artist, when she was just 19 and working as a milliner's assistant. She soon became Rossetti's model, student, lover and muse (she also modelling for other Pre-Raphaelite artists, including famously as John Everett Millais' Ophelia (1851-52)). Some of Rossetti's most adoring sketches and poetry were dedicated to Siddal. And though they married (in 1860), their relationship was tumultuous and not helped by Rossetti's philandering and Siddal's laudanum addiction. In February of 1862, Elizabeth Siddal, heartbroken by another year of Rossetti's affairs, and after suffering her own miscarriage, took an overdose of laudanum and died. Rossetti, overcome by grief and guilt, buried his manuscript of half-finished poetry with his wife, laying it under her hands and surrounded by her swathes of copper colored hair. He then idealised her image as Dante's Beatrice in his painting Beata Beatrix(1864-70).

While married to Siddal, Rossetti engaged in sexual relationships with several other prominent models, one of which was Fanny Cornforth. Whereas Siddal tended to model for mythological heroines, Cornforth modelled for Rossetti's more sensuous portraits. Given that Corthworth had worked as a household servant and a prostitute, there was a clear class disparity between the two yet it is known that Rossetti adored Cornforth and the pair remained close until his death. Rossetti had a second important relationship outside of his marriage, with Jane Morris. The wife of his younger contemporary and admirer, William Morris, Jane was unhappy in her marriage, and had known Rossetti, for whom she too had modelled, since the late 1850s. When Rossetti and William Morris went into business together by creating a Furnishing and Decoration business (Morris & Co.) in 1861, the two became even closer. Their affair is believed to have begun certainly by 1865, and increased in intensity after William Morris left the two alone together for a summer to decorate the couple's new house in 1871 (seemingly with some awareness of the pair's clandestine relationship).

Late period and death

After Lizzie's death, Rossetti's behaviour became more erratic. He moved into a Tudor House in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, accompanied by Fanny who resided nearby and who became his "housekeeper." Rossetti surrounded himself with extravagant furniture and exotic pets, including a wombat, cowboy-hat-wearing toucan and a llama! The astonishing house was captured by watercolorist Henry Treffry Dunn, who recalled such details as an "original make-up of Chinese black-lacquered panels bearing designs of birds, animals, flowers and fruit in gold relief."

During the 1860s and early 1870s, Rossetti remained prolific in his portraits of beauties. Not only did he continue to paint Fanny and Jane Morris, he also discovered a new model, Alexa Wilding, a dressmaker and actress. He in fact painted more finished works of Wilding in this period than any of his other models. This is due perhaps to the fact that they were not romantically entangled, although the two were close friends.

By this late period in his life, Rossetti was desperate to realize his lifelong aspirations as a poet. However, his main body of poetry had been buried with Lizzie Siddall in Highgate Cemetery. In an erratic move, Rossetti exhumed his wife's grave in 1870. He published his first volume of poems in the same year, under the title Poems by D.G Rossetti. However, the work was poorly received and considered overworked and eroticized; an example of "the fleshly school of poetry" as critic Robert Buchanan disparagingly described it. The disappointment of the poor reception of his poems, and a slowing in his painting output, contributed to a mental breakdown in the summer of 1872. Rossetti began to self-medicate with whiskey and chloral hydrate, until he became severely addicted. In 1874, his circumstances declined even further when William Morris cut Rossetti out of their shared decorative arts firm.

For the remainder of his life, Rossetti became a recluse at Cheyne Walk, housebound due to alcohol psychosis, liver damage, and paralysis of the legs. He died on Easter Sunday of 1882, at the age of 53. Until the very end, Fanny Cornforth had visited and nursed Rossetti (even after she married another man in 1879). His most sensuous and passionate of models and lovers became a lifelong friend and confidante, and went on to pass many of Rossetti's paintings and memorabilia onto future generations.

The Legacy of Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Rossetti was a driving force of the Brotherhood, and artists artists who came to follow him into the second wave of the Brotherhood from the 1850s onwards. Most significantly, this included William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and John William Waterhouse. This generation greatly admired Rossetti, particularly his decorative medieval style and Rossetti was a great influence on the Arts and Crafts Movement that Morris went on to form in the 1880s. Following his death, Rossetti was held up as a precursor to Aestheticism and European Symbolism. The cult of beauty and "art for art's sake", alongside a decadent approach to life, were integral to artists and poets such as Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde. Yet after the turn of the century, Rossetti and the other Pre-Raphaelites fell out of fashion. In the aftermath of the First World War, many modernists associated these artists with a suffocating Victorian culture and/or a kind of decadent blindness to the ills of society and awfulness of the war to come.

In the 1940s, Rossetti found the most unlikely of admirers in realist urban painter L.S Lowry. While Lowry painted the grim realities of working life in Manchester, he also was an enthusiastic admirer and collector of Rossetti's work. He even set up the "Rossetti Society" in 1966. He was especially fascinated with Rossetti's visions of female beauty, stating that "I don't like his women at all, but they fascinate me, like a snake." When Lowry died in the 1970s, he left many significant Rossetti paintings to the Salford Museum in Manchester. It is known too that the author J.R.R Tolkien took inspiration from Pre-Raphaelite scenes for his vision of "middle-earth" as imagined in his Lord of the Rings universe.

Today, Rossetti's work is reproduced en masse and widely exhibited. His painting Proserpine sold for over $5 million in 2013, setting a new record for Rossetti's work. Critical perspectives on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood now view the group as the first truly modern British artists; art historian Jason Rosenfeld describes them in fact as the "YBA's of their generation." Rossetti's personal life is also the subject of much retelling and fictionalization, with continued fascination in the women behind the portraits. Contemporary Australian photographer Donna Stevens has recreated Rossetti scenes for the modern age, including her 2015 Love Letters to Rossetti portrait series.

Influences and Connections

-

![John Ruskin]() John Ruskin

John Ruskin -

![Dante Gabriel Rossetti]() Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Dante Gabriel Rossetti -

![Sandro Botticelli]() Sandro Botticelli

Sandro Botticelli - Ford Maddox Brown

- Boccaccio

-

![Romanticism]() Romanticism

Romanticism - Italian Medieval painting

-

![William Morris]() William Morris

William Morris ![Edward Burne-Jones]() Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones- William Bell Scott

-

![Aubrey Beardsley]() Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley -

![Oscar Wilde]() Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde - John William Waterhouse

- J.R.R Tolkien

- Tom Hunter

-

![The Pre-Raphaelites]() The Pre-Raphaelites

The Pre-Raphaelites -

![Arts and Crafts Movement]() Arts and Crafts Movement

Arts and Crafts Movement -

![Aesthetic Art]() Aesthetic Art

Aesthetic Art - European Symbolism

- 1960s Counterculture

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI